The Royal Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial is by far the largest monastery in the country. Indeed it is one of the grandest buildings period. The whole structure of El Escorial is so grandiose that it seems to take up more space than the little town that surrounds it (which is also called El Escorial). Though ensconced in this village, the monastery sits isolated and alone, cordoned off by official buildings that separate it neatly from rest of the town. It is a world unto itself.

El Escorial is perched up in the Madrid Sierra—the same mountain range as Rascafría and Cotos—surrounded by the beautiful forest of La Herrería. It can be easily visited in a day-trip from the center of Madrid, either by bus (line 661 or 664 from Moncloa) or by train.

As one approaches the entrance of the monument, the mountains comes into view, looming beyond, with clouds hovering menacingly over their peaks. The building’s massive form and commanding position high up in the mountains, overlooking the surrounding plains, reveals its origin and function. Though a monastery, the primary purpose of El Escorial has from the first been as a Royal Residence. It was built during the reign of Philip II, one of the most powerful rulers in Spain’s history and indeed the history of the world. For this was the apex of Spain’s might, both on the European continent and worldwide as a colonial superpower.

Nevertheless, such a wild, gloomy, and isolated place (for there was no village here when construction began) is not an obvious spot for a palace. El Escorial seems to exemplify Philip II’s reputation as a dour, dedicated, and antisocial ruler, the personification of the Counter-Reformation. Yet for my part I can see why such a busy and harried man—he ruled over a considerable slice of the world, after all—would want a peaceful place to which he could retreat and focus.

Construction of El Escorial began in 1563. The monastery owes its design to Juan Bautista de Toledo, whose death prevented him from seeing through its completion. That was left to his more famous pupil, Juan de Herrera, whose style has since become synonymous with the Spanish Golden Age, and which has since been imitated in many modern Spanish buildings. The gargantuan heap of stone was completed in 1583, having taken less than 21 years to complete.

Visitors of El Escorial follow a prescribed route through the old hulk. Exploring the monastery for the first time can feel like getting lost in a labyrinth, so many twists and turns does the path take. The visit can also be rather overwhelming, since there are so many things to see: famous works of art, royal apartments, an emormous basilica, the royal mausoleum, and more.

The first stop on the itinerary was a chamber dedicated to a single painting: El Calvario by Dutch painter Rogier van der Weyden. (In English, the painting is simply called The Escorial Crucifixion.) The painting is kept in a darkened room, surrounded by information about its history and the costly restoration needed to rehabilitate the time-worn work. As one would expect from a Van Der Weyden crucifixion scene, the painting is a masterpiece. It fully exemplifies the painter’s talent for creating solid, voluminous forms. The work does not so much convey movement and passion, but calm resignation, quiet tragedy, and somber stillness.

Near this room is the stairwell that leads into the Bourbon apartments. For me this is the least interesting part of the monument, looking for the most part like generic palace rooms. But there are some excellent tapestries on display, some of whose designs were drawn by Goya.

The next stop is the palace of Philip II himself. Though ornate, these rooms are more tasteful and bare than the Bourbon palace. Some items deserve special mention. There is a clock in the study with a little torch attached to the front of it, so you could see the time at night—the original version of a backlit watch. Yet perhaps the most scientifically significant item on display is Philip II’s wheelchair. The king had a bad case of gout, you see, which caused severe swelling and arthritic pain in his feet and legs. The chair has both arm- and leg-rests to elevate his sore limbs, but would require attendants to move it. History aside, the chair is a rather pathetic reminder that nobody, not even kings, are immune from sickness.

There were portraits and paintings adorning every wall: some depict members of the Hapsburg dynasty (each equipped with their distinctive chins); some are religious paintings; several are maps; and some are paintings of palaces in Spain, including El Escorial itself. In two of the rooms there is a sun dial, a metal strip on the floor, marked at intervals, with a little hole in the ceiling above. I think one would have to close all the windows to use it.

But the most beautiful objects in those apartments, for me, are the wonderfully ornate wooden doorways that connected room to room. Without paint, the designer has inlaid scenes and decorations in the surface—floral designs and landscapes—by using lighter and darker pieces of wood. Every square inch of the doorways is meticulously detailed. Just trying to fathom how much time it would take to put something like this together takes my breath away.

Near the apartments, up a flight of stairs, is the Sala de Batallas, or the Room of Battles. It is a hallway with an arched ceiling, almost two hundred feet long. It takes its names from the gigantic and elaborate frescos depicting notable Spanish battles. Here we see charging cavalry, marching infantry, men fighting with pikes, guns, and swords; cities are besieged, ships attacked and sunk. The frescos, which are more figurative than realistic, are the handiwork of Niccolò Granello, an Italian painter who worked in Spain.

The room is a brilliant piece of propaganda, a monument to the military triumphs of Golden Age Spain. One scene depicts the Battle of La Higueruela, fought in 1431 between the forces of Juan II of Castile and the Muslim Nasrid dynasty. We also see the naval battle of Ponta Delgada, fought off the coast of the Azores islands between Spanish and French troops, in 1582. There are also numerous scenes from the Italian War of 1551, fought between Holy Roman Emperor (and Spanish king) Charles V and the French king Henry II. All of these battles were, of course, won by Spanish forces.

After leaving this room, one enters a dark hallway that leads down a very forbidding set of stairs, deep into the basement of the building. At the bottom the visitor finds one of the most remarkable rooms in the whole country.

This is the Panteón de Reyes, or the Mausoleum of Kings. Here is buried nearly every king and queen of Spain since Charles V (Charles I of Spain), Philip II’s father. (The two exceptions to this are Philip V, who is buried in the palace at La Granja, and his son Ferdinand VI, who is buried in the Church of the Monastery of the Salesas Reales, in Madrid.)

The mausoleum is so extravagantly ornate that it is almost oppressive. Gold is everywhere, the walls, the ceiling, the chandelier, the window-panes, the columns, the angelic candle-holders, and the sarcophagi. These sarcophagi line the eight walls of the octagonal room from the floor to the ceiling, even above the door. They are made of dark Toledo marble and each has a gold plate on the front with the name inscribed.

For most of her history, Spain has followed the French tradition of only allowing male monarchs. The only exception to this is Isabel II (who reigned 1833 – 1868), whose accession to the throne caused a war, partly because of her sex. Thus, the women buried in this chamber are, for the most part, Queen consorts—the wives and mothers of kings. Another notable exception is Juan, Count of Barcelona, and his wife Maria de las Mercedes, whose remains will occupy the remaining two sarcophagi above the door. Though son of Alfonso XIII, Juan himself was prevented from ever becoming king by the Spanish Civil War, though his son did. What will be done with the remains of the Juan Carlos I (who is living, but has abdicated) and his wife Sofia, or current and future kings of Spain, has yet to be decided. It seems that Philip II did not anticipate the kingdom lasting this long.

Looking at the marble sarcophagi I wondered why all the monarchs of Spain were so short, since the tombs measure scarcely five feet. The answer to this puzzle is that the bodies are allowed to fully decompose before they are placed in the royal receptacle. This decaying is done is a special chamber called the pudridero, which lay somewhere deep in El Escorial. Only monks can visit these chambers, though presumably they do so infrequently, considering that it takes fifty years for bodies to fully decompose. This is where Juan, Count of Barcelona, and Maria de las Mercedes are now.

Few places in Spain, if any, contain such an overwhelming sense of history as this mausoleum. Some of the most powerful men and women in history lie here, dust and ashes. Rulers from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century lay side by side, one atop the other.

Right next to this mausoleum is the Panteón de Infantes. The Infantes were the sons and daughters of monarchs who did not themselves become monarchs. There are six or seven different chambers, with sixty available spaces, of which thirty-seven are occupied. The most recent burial was in 1992, of Juan Carlos I brother Alfonso, who was shot in 1956 (he had been decomposing in the meantime; the Infantes have their own pudridero).

The most notable and impressive tomb in this mausoleum is that of John of Austria. He was the “natural” (read “illegitimate”) son of one of Carlos V. This Infante was one of the commanders of the Christian forces (composed of Spanish and Venetian galleys) against the Ottoman Turks in the Battle of Lepanto. (Miguel de Cervantes also served in this battle, in which he permanently lost the use of his left hand.) The commander’s tomb is excellent: John is laying down in death, his head resting on an exquisitely sculpted pillow, with a serenely peaceful and noble expression on his mustachioed face. He is dressed neck to toe in fine armor, and is holding a real metal sword.

The other tomb which impressed me was hardly a tomb at all, but an ornate mass grave. It was the collective coffin for the numerous sons and daughters of the king who had died before puberty. The tomb is a regular polygon with twenty sides and two levels, which makes for forty slots—forty young bodies. This richly decorated tomb, with the emblems of royalty painted on every side, is a monument to the advance of medical technology. For every Spanish parent nowadays is better off than were those kings and queens, buried in tombs of marble and gold, who could afford the best doctors money could buy and power could persuade.

Next I ascended another staircase and found myself in a large hallway with an arched ceiling, covered in ornamental painting. This is El Escorial’s art museum. Tastefully arranged throughout this hallway were paintings by Titian, Tintoretto, José de Ribera, Velazquez, Bosch, and El Greco—among others. Every one of these paintings has a religious theme. There were pictures of saints in the wilderness, contemplating crucifixes; of saints being martyred, a knife to their throat; of saints contemplating heaven, face upturned; of the Last Supper and the Crucifixion, and more. The famously pious Philip II was responsible for most of this collection.

The highlight of the museum is likely El Greco’s Martyrdom of Saint Maurice, which Philip II apparently disliked since the painter relegated the scene of the actual martyrdom to the background.

The museum leads into the richly decorated cloister, with its walls decorated with brightly colored frescos of the life of Jesus. From here you can see the principle stairwell, whose ceiling is covered in a magnificent fresco of a heavenly scene.

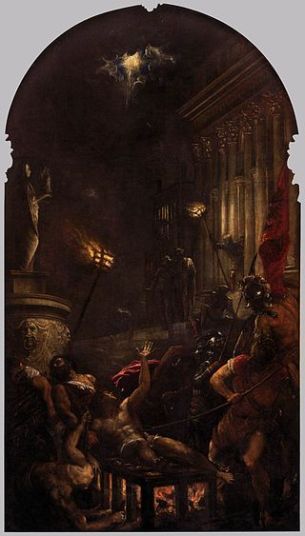

Nearby is a room called the “old church,” though I admit I am not sure why. In any case, it is a bare room, the only decoration being a few paintings on the walls. The most notable of these is by Titian: The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence. According to tradition, St. Lawrence was killed by being roast alive on a gridiron; and while he was being killed, he supposedly called out to his torturers “I’m well done! Turn me over!” (This is part of the reason why he’s the patron saint of comedians.) Titian’s considerably grimmer version was first made at the behest of the Church of the Jesuits, in Venice. When he saw it Philip II liked it so much he asked the painter to make a copy, which still stands in the Escorial.

Saint Lawrence (San Lorenzo in Spanish) is obviously an important saint for El Escorial, he being its namesake. According to legend, the very floor-plan of the El Escorial monastery was based on the interlocking bars of a gridiron, in honor of St. Lawrence. This is untrue, apparently, though the floorplan is notably grid-like.

After seeing all this—which does not even constitute the half of the massive building—I still had not even broached the largest and grandest space in El Escorial: its central basilica.

It is as large as many cathedrals. The stone ceiling towers high overhead, covered in frescos that are difficult to clearly observe in the dim light from so far away. Paintings hang in little niches all throughout the space: including ones by Titian, Ribera, El Greco, and Zubarán. The main altar is an elegant piece that stands over 90 feet tall. False columns divided it into a dozen niches, in which are either paintings or sculptures. In the very center, below Jesus and the Virgin Mary, was another painting of St. Lawrence being burned, this one by Pellegrino Tibaldi. (The Titian painting was originally destined for this space, but it was too dark in the dim light of the basilica).

The most distinctive aspect of the basilica’s decoration are the statues flanking the main alter. These are shimmering golden sculptures of two royal families, knelt in prayer. To the left of the altar (as the viewer faces towards it) is Carlos V, his wife, and children; to the right is Philip II, two of his wives (not simultaneous), and a son. These sculptures are marvelously rich, each figure wearing finely detailed armor or ornate dress, each one draped in a cape or a robe—and the capes of the kings are painted with the royal insignia.

And yet the most notable artistic work to be found in the cathedral is in a little chapel to the left of the door (again, facing towards the altar). Here you can find a life-sized, white marble crucifix sculpted by the famous Renaissance artist Benvenuti Cellini. It is here because it was given as a gift to Philip II by the Grand Duke of Tuscany. The finely made crucifix is one of the few in the world that depicts Christ as fully nude; as such, it is displayed with a white clothe hanging around its waist.

After exiting the Basilica the visitor enters the Patio de los Reyes, or the Courtyard of the Kings, where one can see the basilica’s façade. The courtyard takes its name from the monumental statues of the Kings of Jerusalem, wielding scepters and wearing crowns of gold, who stand above the entrance. From here there is only one more stop on the itinerary: the Royal Library.

This was one of the greatest libraries of the Renaissance, whose presence here contradicts the dour and anti-intellectual reputation of Philip II’s Spain. Yet the choice to put the library here in the mountains, far from any established university, was not without its controversy. Whatever the library lacks in convenience to would-be scholars, however, it makes up with its beauty.

Like the Sala de las Batallas, the main room of the library is rectangular, with a vaulted ceiling, stretching to well over 150 feet in length. The decorated barrel vault is undoubtedly the main attraction: for here we have a allegorical representation of the liberal arts: the Trivium (Grammar, Rhetoric, and Dialectic), and the Quadrivium (Arithmetic, Music, Geometry, and Astrology), not to mention Philosophy and Theology. I particularly like the representation of Philosophy, since it shows the Muse convening with Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Seneca. Also to be found are Virgil, Livy, Cicero, Demosthenes, Euclid, and many other intellectual heroes of antiquity.

But it is a library, so there are also books to be found. There are no labels or explanatory plaques, so it is difficult for me to give an account of them. A fire destroyed some of the collection in 1671, and Napoleon’s troops carried off some more after they conquered Spain. (This, by the way, is why the National Gallery in London has a famous painting of Philip IV by Velazquez. It originally hung in this library, but Joseph Bonaparte snatched it, and the painting eventually made its way to England.) Paintings of Carlos V and Philip II still hang here; and the library still boasts an important collection of Latin, Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, and early Castilian manuscripts. Some of these volumes are opened, revealing the beautiful illustrations that accompany these hand-made books. In the center of the room runs a corridor, in which are displayed scientific and astronomical instruments. It is a veritable temple of learning.

From all this, I hope you can see why El Escorial is arguably the most extraordinary building in a country full of extraordinary buildings. It has the royal mausoleum, a historical library, a palace (actually two), a painting gallery, including several famous works, a massive basilica, and a monastery—and all of this contained within a single magnificent building. If you are like me, when you are finished you will have that museum-goers headache that one gets from trying to absorb too much information.

But once you exit the monastery there is still more to see. For the town of El Escorial itself is attractive. If you visit during Christmas you can see the town’s famous Belén (nativity) display in the main square. Every Christmas, the people erect life-sized plaster sculptures of the Virgin and Child, the three kings, as well as a whole scene with villagers, donkeys, horses, pigs, chickens, and even an elephant and a giraffe. These sculptures are not incredible works of art, you understand, but they are a comical reminder that the very same culture which had given rise to the monastery lives on.

The town itself is built of the same stern granite as the monastery itself; and its twisting, steeply inclined streets are home to many fine restaurants. From the Parque Felipe II, near the bus stop, on a clear day you can see the foothills of the mountains spread out before you, with Madrid in the distance. There are also two excellent parks, the Park of the Casita del Principe and of the Casita del Infante, the latter of which offers a great view of the monastery. Every time I visit El Escorial I discover something new to appreciate. It is one of the jewels of Spain.

This was a wonderful tour of one of the most emblematic monuments Spain has.

LikeLike