A Promised Land by Barack Obama

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Barack Obama rose to national prominence after giving the speech of his life at the 2004 Democratic Convention. I remember it. I was 13 at the time, on a camping trip in Cape Cod, listening to the speech in a tent on a battery-powered radio. Though I was as ignorant as it is possible for a human to be, I was completely electrified by this unknown, strangely-named man. “That should be the guy running for president!” I said, my hair standing on end. Four years later, I watched Obama’s inauguration in my high school auditorium, cheering along with the rest of the students, and felt that same exhilaration.

I am telling you this because I want to explain where I am coming from. Obama was the politician who introduced me to politics, so I cannot help but feel a special affection for him. You can even say that Obama was foundational to my political sensibilities, as he was president during my most sensitive years. This makes it difficult for me to view him ‘objectively.’

In this book Obama displays that quality which, despite him having almost nothing in common with me, made it so easy for me to identify with him during his presidency: his bookishness. He is clearly a man delighted by the written word. And Obama is able to hold his own as a writer. While I do think his prose is, at times, marred by his having read too many speeches—his sentences crowded with wholesome lists of good old fashioned American folks, like soccer moms, firefighters, and little-league coaches—the writing is consistently vivid and engaging, pivoting from narrative to analysis to characterization quite effortlessly. If Obama is guilty of one cardinal literary sin, it is verbosity. This book—700 pages, and only the first of two volumes—could have used a bit of chopping.

Obama is notorious for his caution, his conservative temperament, his insistence on seeing issues from as many perspectives as possible. But what struck me most of all in this book was his confidence. Aiming to justify himself to posterity, I suppose, Obama spends the bulk of this book explaining why he made the right decision in this or that situation. Indeed, Obama attributes even his few admitted missteps to noble intentions gone awry.

As Obama goes through the first term of his presidency, explaining how he tackled the financial crisis, healthcare, global warming, or the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the central tension of his presidency becomes apparent: the conflict between idealism and realism. Obama the speaker is, as I said, electrifying—soaring to rhetorical heights equaled by very few politicians. And yet Obama the president does not soar, but plods his way forward, examining the earth for any pitfalls five steps in advance. Indeed, I think Obama’s philosophy of governance could by fairly described as technocratic, preoccupied with effectiveness rather than liberty or justice.

This, I would say, is the central flaw in Obama’s governing philosophy. Obama ran for office with a simple message: the promise that we Americans could put aside party loyalty and work together towards a common goal. But this both underestimates and overestimates the forces that pull us into competing factions. In other words, this is both naïve and slightly cynical. Naïve, by failing to understand that politics is about power, and that there was more power to be gained through division than unity. But cynical, by considering our differing political ideologies to be superficial and ultimately unimportant.

Obama seemed to believe that the goals were obvious—that we all basically agreed on the sort of country we wanted to live in—and that the only thing needed was somebody competent enough to actually get the job done. Admittedly, this is quite a compelling idea, even an inspiring one in its way; and Obama is a very convincing proponent. But the limits of this thinking are on display all throughout this book. Obama is constantly making pre-emptive concessions to the Republicans, thinking that a market-friendly healthcare plan, or a strong commitment to killing terrorists, or a more modest stimulus bill will win them over, or at least mute their dissent. The consequence is that, in his policy—such as the deportations or the drone strikes (hardly mentioned here)—he is sometimes unfaithful to the principles he so eloquently expounds at the podium.

I am being somewhat critical of Obama, which is difficult for me. He was subjected so much silly and unfair criticism during his presidency that it can feel mean to add to this chorus of contumely. And I do not wish to take away from his very real accomplishments. Compared to either the administrations that came before or after his, Obama’s presidency was an oasis of calm, sensible governance. Though the fundamental change promised by his campaign failed to materialize, by any conventional standard Obama’s policies were successful—helping to heal the economy, expand healthcare, and slowly disentangle us from foreign wars.

It is also difficult to criticize Obama because it is clear that so much opposition to him was fueled by racial resentment. Obama was continuously subjected to a double-standard, constrained in the things he could do or say. No story better illustrates this than the Henry Louis Gates arrest controversy. After Obama rightly called the decision to arrest a black Harvard professor on his own property ‘stupid,’ the political backlash was so fierce that he had to recant and subject himself to an insipid ‘beer summit.’ And, of course, the moronic birther controversy speaks for itself. In short, it is difficult to imagine the opposition to Obama’s policies being so fierce and so persistent had he been a white man.

I listened to a part of this book on January 6th, the day of the Capitol Riot. After watching the events unfold on the television all day, I decided I could not take anymore, and went out for a walk. As I strolled along the Hudson River, I played this audiobook, listening to Obama narrate his presidential campaign. The contrast between that time and this was astonishing. I could not help but feel nostalgia for those days of relative innocence, when Obama’s “You’re likable enough, Hillary” qualified as a scandal. But I also could not help wondering to what extent, if any, Obama was responsible for what was becoming of my country. If he had embraced bolder initiatives, rather than striving to be as respectable as possible, could he have staved off this backlash of white rage? It is impossible to say, I suppose.

In the end, if I came away somewhat disappointed from this book, it is only because the Obama I found did not measure up to the messianic figure I embraced as an adolescent. But that is an unfair standard. Judged as a mere mortal, Obama is as about as impressive as any person can be—a man of prodigious talents and keen intelligence, whose presidency provided a relief from the onslaught of Republican incompetence. For that we can say, thanks, Obama.

View all my reviews

Month: January 2021

Boston: On the Trail of Freedom

I visited Boston by accident. It was a wedding (second cousin, once removed). On a cold December day between Christmas and the New Year, before the nuptial celebrations commenced, I found myself with some time to kill in this historic New England city. So I figured I would use the opportunity to walk the Freedom Trail.

The Freedom Trail is a walking path linking several historic sites in the city of Boston. Most of these have something to do with our Revolutionary War. In the 1770s, Boston was hotbed of rebellious fervor. John Hancock, Paul Revere, and Sam Adams, early advocates for independence, lived here, as did Sam’s more moderate second cousin John. So it was here that the growing dissatisfaction with British rule first spilled out into conflict and bloodshed. This history can be followed as it unfolds along the Freedom Trail.

The path begins in Boston Common. This is a park in the center of the city, which holds the distinction for being the oldest public park in the country, as it was opened in 1634. When I visited it was a cold and dreary day, which makes it difficult to judge the park’s comeliness. But overlooking the Common is the Massachusetts State House, a very attractive building designed in the Federal style by Charles Bulfinch, which houses both the governor’s offices and the state legislature.

Standing before this building, on the outer edge of the Boston Common, is the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial. Shaw, as you may know, was the white colonel who led the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment during the Civil War, which was composed of free black soldiers. Allowing black people to serve in the military was considered a radical step at the time; but it also was a kind of symbolic victory over the southerners who were fighting to preserve slavery.

The monument itself was a sensation: its opening was attended by the philosopher William James, the sociologist W.E.B. DuBois, and the educator Booker T. Washington, among other notables. And while the monument did attract criticism during the George Floyd protests—for it portrays the white commander above and in front of his black troops—I think that it was actually radical in its own day. It depicts the black soldiers as dignified, powerful, and fully individual. One need only compare this monument to the Emancipation Memorial (recently removed) in Boston, which shows a black man crouching beneath Lincoln. The soldiers in the Shaw Memorial do not kneel, but march resolutely.

Continuing along the trail, we immediately come upon the Park Street Church, a very attractive place of worship built in the first years of our Republic. Nextdoor is the Granary Burying Ground, so named because a granary used to occupy the space where the church now stands. The visitor enters through a mock-Egyptian gate into what is the third-oldest cemetery in Boston (founded in 1660). Quite a few heroes of the American Revolution are buried here. There is Samuel Adams (1722 – 1803), the aforementioned firebrand who helped to spark our rebellious spirit, as well as Paul Revere (1734 – 1818) of Midnight Ride fame. Aside from Adams, two more signers of the Declaration of Independence are in attendance: Robert Treat Paine (little remembered these days) and the man whose name survived in his oversized signature, John Hancock (1737 – 1793).

But that is not all. All five victims of the Boston Massacre are buried here. To recount the event dispassionately: An inflamed mob started to throw stones and other things at a garrison of British Soldiers, one of whom fired without orders, causing his comrades to follow suit. Five Americans died from the gunshots. John Adams, who was simply a lawyer at the time, took it upon himself to defend the British soldiers in court, and for the most part succeeded. But the massacre was a decisive step on the road to revolution, as it mustered colonial support more effectively than any speech could. As it turns out, citizens tend to be upset when the forces meant to protect them instead shoot them dead.

The next stop on the trail is another church and burying ground. King’s Chapel is a lovely stone church designed by Peter Harrison, one of the first trained architects to work in the American colonies. Next door is the King’s Chapel Burying Ground, which actually predates the church by over a century, as it is the oldest cemetery in all of Boston (established in 1630). The cemetery does not contain as many famous bodies as the Granary Burying Ground, but some names stand out for comment. Mary Chilton (1607 – 1679), supposedly the first woman to step foot in New England from the Mayflower, was laid to rest here, as was John Winthrope (1587 – 1649), the third governor of the Massachusetts colony. But most consequential may be Frederic Tudor, the so-called “Ice King,” who made a business cutting and shipping blocks of ice from the frigid ponds of Massachusetts. This was both a major innovation and an inspiration for the refrigeration that all of us now take for granted.

The next stop, just down the street, is the old site of the Boston Latin School. This is a venerable institution of public education—indeed, the oldest public school in the United States. And it is still active, though it has since moved to more ample accommodations than the little building that once stood here. Its presence is marked by an elaborate plaque in the ground. Nearby is a statue of the school’s most famous dropout: Benjamin Franklin. The portly and balding Franklin is honored beside perhaps the most famous mayor of Boston, Josiah Quincy III, whose namesake is the Quincy Market in central Boston. These two eminent men stand before the Old City Hall—serving that purpose from 1865 to 1969—a lovely old relic built in the French Second Empire style

Continuing down the street, we reach the Old Corner Bookstore. This is an attractive brick building, built in 1718 to be used as an apothecary shop with an attached residence. The place became a bookstore in 1828; and shortly thereafter, starting from 1832 and on to 1865, it was used by Ticknor and Fields, a publishing company. Though long forgotten, Ticknor and Fields published some of the most significant American writers of the day, including Emerson, Hawthorne, and Longfellow. They even published Dickens’s books in the United States. As a result, this humble building came to be a meeting place for men (and women) of letters. Unfortunately, after such an illustrious history, this noble edifice is now the home of a Chipotle restaurant. Meaning no offense to big burrito lovers, I will venture to say that this building deserves better.

Right nearby is the Boston Irish Famine Memorial. This is a group of statues—two families of three—that contrasted the lives of those who left Ireland and those who remained. The family that emigrated is shown happy and healthy, while the family stuck in Ireland is on the verge of death. While the artistic merits of the memorial are not beyond dispute, it is certainly right to have a monument to the Irish in Boston, as the city was dramatically shaped by the influx of Irish in the 19th century. Indeed, Boston reminded me of no city more strongly than Dublin—its brick architecture, tight and chaotic streets, and dour atmosphere. At a glance, one could easily mistake historic Boston for the capital of Ireland.

Next on the trail is the Old South Meeting House. This is a plain but elegant brick Congregational church, with a tall white wooden spite—a typical New England aesthetic. The whitewashed interior is filled with boxes of pews, arranged like an enormous maze. This church is not notable for its aesthetic, however, but for its role in the Revolutionary War. After the Boston Massacre of 1770, annual memorials were held here, complete with fiery rebellious rhetoric. Then, in 1773, thousands of irate colonists met here to discuss the much-hated Tea Act, a tax on imported tea. From here, everyone knows the story: A group of a few dozen colonists—some dressed as Native Americans—raided three English merchant vessels in the harbor, and chucked all the tea overboard. This was the Boston Tea Party

Soon we come to the Old State House. And here, the contrast between the old and the new Boston is quite apparent, as this erstwhile commanding structure is now completely dwarfed by the buildings and skyscrapers all around it, in what is now the financial district. But the building is still attractive and graceful. As the name suggests, this building served as the original Massachusetts State House, before it was replaced by the current one (described above). Indeed, built in 1713, the Old State House was used for government affairs long before independence, making it one of the oldest public buildings in the country. Nowadays it is the home to a museum; but I admit the entry fee put me off, and I only browsed the gift shop—filled with the expected touristy stuff. Notably, the museum has a vial containing some tea from the Boston Tea Party, snuck into a raider’s boot. The site of the Boston Massacre is commemorated nearby, in the form of a stone circle.

Now we enter Government Center, the part of town where we can find the modern City Hall. Unfortunately, this enormous hunk of brutal concrete compares quite unfavorably with the pretty constructions we have seen so far. Apparently gaining our independence did not advance our taste. The contrast is immediate when we turn our attention to our next stop, yet another big brick building with a white spire: Faneuil Hall. This building served as both meeting house and marketplace in colonial Boston. Firebrands like Samuel Adams gave seditious speeches in the building’s Great Hall, a task for which he is now commemorated with a nearby statue. Faneuil Hall owes its name to a slave trader, who sponsored the project with his ill-gotten gains. Slaves were even sold here. But that original building mostly burned down in 1761, passing along its name to the current edifice. So far, activists have not succeeded in changing its appellation.

The building’s Great Hall—an enormous auditorium filled with wooden chairs—is now decorated with portraits, paintings, and other sorts of patriotic paraphernalia. It is still used for meetings, organizing, and ceremonies. “Faneuil Hall” is not only used to refer to this building, however, but sometimes to this entire area, a hub of nightlife and a great place to grab a bite to eat. This is partly because the old marketplace has been supplemented by the enormous Quincy Market, named for the Quincy mayor we met earlier. This is a long, open building filled with food stalls and a fair share of touristy junk. I enjoyed walking through the busy space, as it at least provided some respite from the cold.

From Government Center, we now walk to North End, the oldest residential neighborhood in the city. As you will probably notice, this area became popular with Italian immigrants, resulting in the plentiful restaurants serving pizza and pasta. More relevant to the Freedom Trail, this neighborhood is also home to Paul Revere’s House. The house actually predates the famous revolutionary by quite a lot: built in 1680, the house was not bought by Revere until 1770. Though the three-storey, timber house does not look like much to the modern eye, at the time it was both spacious and luxurious, befitting Revere’s status as a prosperous silversmith (there are examples of his work inside). Sold by Revere, and subject to the whims of the market—among other things, it was used as a shop and a tenement—the property was eventually bought by Revere’s grandson, who began the process of restoring it and turning it into a museum. Nowadays, one must pay to enter. Freedom has its price, after all.

Onward, we reach the Old North Church. Once again, we are confronted with a big brick church with a white spire, whose whitewashed interior is filled with wooden boxes for pews. But perhaps the Old North Church does deserve credit for originality, as it is the oldest extant church in Boston. The competition is close: built in 1723, the Old North Church beats the Old South Meeting House by six years. This church was where the iconic lanterns of Paul Revere’s ride—one if by land, two if by sea—were so briefly hung, in order to warn the colonial militia of the approach of the British Army. Revere himself rode his horse to deliver the message to the troops waiting in Lexington and Concord, though he almost certainly was not shouting “The British are coming!” as that would have blown his cover. As it was, Revere was still arrested by the British, and very nearly executed. His patriotic messenger service is now commemorated by a statue of the man on horseback.

Now we come to yet another cemetery, the Copp’s Hill Burying Ground. As its name suggests, this is situated on a slight hill, giving the visitor a decent view of the River Charles. Founded in 1659, Copp’s Hill is the second oldest cemetery in Boston (29 years after King’s Chapel, but one year before the Granary), and it has its fair share of venerated bodies. Paul Revere’s less-famous fellow rider, Robert Newman, is interred here, as is the poet Philis Wheatley, the first African American woman to be published. But Copp’s Hill is more appealing simply for its landscaping, providing a much-needed relief to the crowded stone and brick streets of Boston. I consider myself something of a connoisseur of cemeteries, and Copp’s Hill is a fine one.

We have a bit of a walk now, as the next stop on the Freedom Trail is across the Charles River. This means walking across the North Washington Street Bridge, which connects North End with the Charleston neighborhood. It would be an exaggeration to say that the bridge is a beautiful piece of engineering, or that the view from the bridge is quite breathtakingly beautiful—especially on a cold, windy, drizzly December day—but I still managed to enjoy the walk. Once across, you turn right towards the wharf, where you may spot the top mast of the next stop in the distance: the USS Constitution.

Now, as it happened, I was visiting Boston during the 2018-19 government shutdown. As a result, the museum attached to this historic war vessel was not open. Visitors were, instead, hastily ushered through metal detectors onto the dock by military personnel (presumably working without pay). In any case, I was able to climb aboard the old ironside and enjoy the charm of an antique vessel. The history of this ship takes us back to the very beginnings of our nation, as it was one of the first six commissioned by the new United States government. Indeed, the Constitution is now the oldest commissioned naval vessel that is still seaworthy. The frigate—equipped with 50 canons—saw significant action during the war of 1812, when it overcame five British warships. This earned the boat legendary status, and it has been kept in good working order ever since. In fact, the boat still has its own 60-person navy crew.

After taking in my fill of the winds and waves, I made my way to the last stop on the Freedom Trail: the Bunker Hill Monument. As you may know, the Battle of Bunker Hill was one of the first and most important of the Revolutionary War. Though the British succeeded in driving the colonial militia from their positions, in their assaults on the rebel position they took heavy casualties, losing far more men than their untrained opponents. According to legend, it was during the first British charge when Col. William Prescott instructed not to fire until they saw “the whites of their eyes.” Unfortunately, there is scant evidence that this dramatic phrase was uttered, and it does seem like a needlessly poetic battle command. What is more, though universally known as the Battle of Bunker Hill, most of the fighting was done on the nearby Breed’s Hill. And this is where the inaccurately-named Bunker Hill Monument is to be found as well.

Built from 1825 to 1843 (they frequently had to stop due to depleted funds), the Bunker Hill Monument is one of the oldest national monuments in the country. And its design was influential. Standing on top of the mound of green earth, a granite obelisk juts 221 feet (67 m) into the air. This design almost certainly provided the inspiration for the tower’s more famous cousin, the Washington Monument. The stone was taken from a quarry in the town of Quincy (the town named after Abigail Adams’s grandfather) and transported to the site via one of the first railroads in the country, the Granite Railway. A statue of Prescott stands in front of the obelisk, not too far from where he likely stood during the battle, looking fearsome and fearless. There is an exhibit lodge next to the obelisk, too, though it was closed due to the shutdown. At least the view was still available—revealing the spires of downtown Boston, the cozy houses of Cambridge, and the industry across the river Charles.

I was very cold by now. My clothes soaked through from the rain, and there was a long walk back to the hotel. But my misery was punctuated by a stop at a restaurant in Chinatown, where I had some delicious noodle soup. Then it was time to shower and get my suit ready for the wedding. And that was it. So, unfortunately, I saw very little of Boston during this trip. I was particularly sorry not to see Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, one of the finest art museums in the country. But what I had seen, during my few hours of exploration, was enough to motivate me to walk several miles in soggy shoes. And that is a pretty high compliment.

I’ve been interviewed!

My best and oldest friend, Oscar Desiderio, has recently embarked on a new project—the Knowledge Daddies—along with two of his comedian buddies, Sean Barry and Andrew Steiner. The three of them interview others about skills they have, and then try to learn these skills themselves. Recently, I have been flattered to be interviewed myself about my upcoming novel.

The interview is available on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. You can follow the Knowledge Daddies on Facebook and Instagram. I believe they will be releasing some video episodes of their online series shortly. In the meantime, enjoy the interview!

Concord and Walden Pond

Through some combination of chance and circumstance, some little places become fulcrums of history. This is certainly true of Concord, Massachusetts.

Boasting a population a little south of twenty thousand, and of no obvious geographical significance, this town nevertheless became the setting of our War of Independence. A detachment of British troops was sent to Concord to confiscate or destroy weapons that they believed were being stockpiled here. But they were met by the nascent American militia. After a brief shootout, the redcoats retreated, demonstrating that the British army was not invincible. This was the battle of Lexington and Concord (there was an earlier skirmish in the nearby town of Lexington), and it took place at the Old North Bridge, which spans the Concord River.

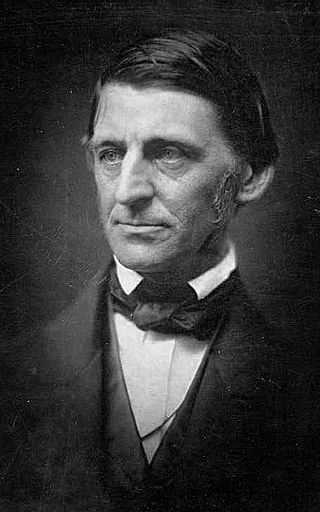

Being the site of the “Shot heard round the world”—as it was later dubbed, somewhat self-importantly—would satisfy most towns the size of Concord. But in the 19th century, this modest municipality once again attracted outsized importance by becoming the center of one of the most important movements in American literature and philosophy: Transcendentalism. This was largely due to the presence of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who moved into town in 1835.

The son and grandson of ministers, Emerson was very much a preacher himself, though of a new religion. Transcendentalism was perhaps the original back-to-nature movement, a celebration of self-reliance and the simple life. The time was ripe for such ideas, and Emerson was its most articulate voice. He attracted a circle of friends and admirers, among whom was Amos Bronson Alcott, a fellow philosopher who sadly lacked Emerson’s gift for expression. Alcott’s most notable venture was an experiment in Utopian living, called the Fruitlands, a kind of agricultural commune whose members adhered to a vegan diet. It soon imploded, and Alcott returned to Concord to live in the now-famous Orchard House with his wife and four daughters. One of those daughters was Louisa May Alcott, who fictionalized her girlhood to create the classic, Little Women. Her literary ability kept the family financially afloat.

The Fruitlands was not the only Transcendentalist experiment in communal living. Another was Brook Farm, also in Massachusetts, and also an attempt to live off the land in perfect equality. The novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne took part in this venture, though he did not stay for long (and Brook Farm did not survive for very long, either) before he, too, moved to Concord. Indeed, he moved into the Emerson family home, the Old Manse, which stands near the famed Old North Bridge. Emerson, meanwhile, moved into a larger house, now an eponymous museum, where he continued to serve as the center of the town’s intellectual life.

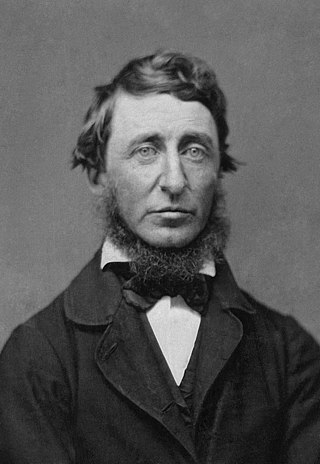

A frequent guest was a young and very earnest man named Henry David Thoreau. Thoreau must have seemed to be an eccentric and marginal character compared to the likes of Emerson. But it was Thoreau who came to epitomize Transcendentalism better than anyone, and Thoreau who immortalized Concord more completely than any writer (with the possible exception of Louisa May Alcott). His fame largely rests upon a single book, Walden, named after a small lake in Concord. In 1845, the young Thoreau decided on an entirely novel experiment: to attempt to live independently in the woods beside Walden Pond. The land was owned by Emerson, who let the young vagrant use it. In Thoreau’s own words:

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

So Thoreau used some recycled materials to build a little cabin with some furniture and commenced an experiment that would last two years, two months, and two days. Later, when he wrote up the experience, he compressed this into an imaginative year, weaving memories into reflections to make an original work of literature. Walden is an odd book by any standard—meandering, prickly, pompous, but also thoroughly original and beautifully written—and it did not find a large audience in Thoreau’s lifetime. In the years since his death in 1862, however, Walden has become one of the most beloved American classics, and Walden Pond has become a site of pilgrimage.

It was certainly in the spirit of a pilgrim that I visited Walden Pond, once in summer, once in winter, both times passing through the town of Concord on my way to someplace else. On my first visit I was filled with anticipation, as though I was about to step into the Sistine Chapel or walk along the Great Wall of China, though in retrospect it is hard to say what I was expecting. Walden Pond is just that—a pond: a body of water, surrounded on all sides by trees. In fact, it is not even treated very reverently by the locals. Now a state park, when I visited in summer there were many locals lounging on the sand, and a few in the water. It is a place for recreation as much as reverence.

Admittedly, the geology of Walden Pond is interesting. A kettle hole lake, it was formed by retreating glaciers during the end of the last ice age, when a hunk of ice broke off the glacier and got lodged underground. As a result, the lake is surprisingly deep: over 100 feet, or 30 meters. But ninety-nine out of a hundred visitors (if not more) would likely not find anything memorable or special about Walden Pond had it not been made famous by Thoreau. And, I realized, this is precisely the message of Thoreau’s book: that anyplace can be made special through focus, attention, and work. With the right eyes, a mundane pool could be just as inspiring as a gothic cathedral.

On my first visit, I walked around the lake to the spot where Thoreau had built his little cabin. It does not stand today, though the spot is marked by concrete pillars. Nearby is a large cairn, where visitors have been pilling pebbles for decades. Before it stands a sign on which Thoreau’s famous battlecry is painted (see above). Once again, rather than any grand monuments, we are confronted only with the woods, the water, and Thoreau’s words.

Not long before my first visit to Walden Pond, I visited the Morgan Library in Manhattan, where I was lucky enough to find a special exhibit on Thoreau. It was extraordinary: the museum had Thoreau’s walking stick, surveying gear, and writing desk. They even had the many volumes of Thoreau’s journals—and he was a prolific diarist, recording both his philosophical thoughts and his observations of the natural world—which served as the basis for his published books. I believe that the bulk of these items were on loan from the Concord Museum, where they normally reside.

During my second stop in Concord, we also stopped by the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. The reader may recognize this name from the legend of Sleepy Hollow, which of course takes place in a cemetery—though not the one in Concord, Massachusetts. The burying ground of Washington Irving’s story is in Westchester, New York: my home town. It seemed very strange to me that two famous cemeteries would bear the same name; and I assumed that the Concordians had copied the Westchesterites. But apparently this is not the case. The Westchester cemetery was formerly called the Tarrytown Cemetery, and only changed its name to honor a posthumous wish of Washington Irving, who died in 1859. The Concord cemetery was established in 1855, and the place had been called Sleepy Hollow before anybody even thought of burying the dead here. So the names are a complete coincidence.

The cemeteries in Westchester and Concord do not only share a name; they were established at almost the same historical moment, and were shaped by the same intellectual currents. Washington Irving was a notable proponent of romantic gardening, wherein the landscape is modified to appear as if it were just a product of nature—albeit a particularly pleasing product. Ralph Waldo Emerson, too, believed that nature should be emulated, not suppressed; and as the designers of Concord cemetery were followers of his, the cemetery incorporates the natural topography—and some original vegetation—into its design. Both places can thus be classed as “garden cemeteries,” far more open and green than what came before.

Luckily for the visitor, most of the famous graves in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery are concentrated in one spot: Author’s Ridge. Here you will find Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Louisa May Alcott, and Henry David Thoreau. Emerson’s grave is by far the most conspicuous: an enormous marble boulder to which a plaque has been fastened. I suppose it symbolizes Emerson’s love of nature to have an unhewn tombstone. Hawthorne’s grave is far simpler: a standard headstone, about a foot high. Thoreau’s and Alcott’s are even humbler; but theirs inspired the most devotion. Alcott’s was covered in old pens and pencils—presumably to honor Jo, Alcott’s writer heroine—while Thoreau’s was adorned with feathers, pine cones, and a bird’s nest. The two of them are still beacons for young minds.

Before we go, another resident of the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery must be mentioned: Ephraim Wales Bull. Not a writer, nor even a Transcendentalist, Bull was responsible for developing the Concord grape, now a ubiquitous varietal. This cultivar was special because, unlike other grape species, it could survive the brutally cold winters of Massachusetts. It was also robust and sweet, making it perfect to eat by itself or to turn into juice and jelly (though not great for wine). Unfortunately for Bull, his grapes were stolen and sold, meaning that he did not profit from his hard word. This is why his tombstone says: “He sowed, others reaped.”

I have gone on and on about the historical importance of Concord, but I must end by noting that it is simply an attractive place. In my all-too-brief time in the town, I was enchanted by the antique houses and churches, so quaint and picturesque. Even if you have little interest in the Revolutionary War or Transcendentalism, and just want to visit a thoroughly charming place, then I propose a visit to Concord and Walden Pond.

Jefferson Country: UVA and Monticello

Thomas Jefferson is an American icon. Virtually every American can recite (or at least recognize) the immortal lines penned by Jefferson, declaring our independence: “We hold these truths…” His face graces the nickel, and his likeness scowled from the now-defunct $2 bill. A veritable Greek temple stands devoted to his form and memory in the nation’s capital; and, in the Black Hills of South Dakota, Jefferson is chiseled into a mountain-side. And yet, if you really want to pay tribute to this foundational father, you must make your way toward the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, to Charlottesville.

In the summer of 2019, my family did exactly that. On the drive down from New York, we even decided to listen to Jon Meacham’s worshipful biography of the man. Unfortunately for us, the book failed to make a good impression; and, as it so happened, Jefferson similarly failed. But I am getting ahead of myself.

This was my first time in Virginia. The summer sun beat down hard, making the rolling fields of grass glow an iridescent green. A friend of my father owns an alpaca farm in the nearby town of Gordonsville, which we visited before dinner, giving me the briefest taste of farm life—new to me.

That night, after dinner, my brother and I wandered into downtown Charlottesville. As we did not wish to visit a bar, there was little to do but walk. But we did happen upon the statue of Robert E. Lee, which has been the center of so much controversy. A 2016 proposal to remove this Confederate monument sparked the now-infamous Unite the Right rally—in which one counter-protester died, and which Trump refused to condemn. After this, the City Council voted to remove the statue; but the state government overrode this decision, and the strange commemoration of a rebel racist stands to this day.

If I had been more aware at that moment, perhaps I would have realized that this embattled statue was only the most visible manifestation of the region’s contested history. The Confederacy may have been defeated, and slavery long abolished; but in Charlottesville, history is still an active warzone. And nowhere is this struggle more apparent than in the town’s most famous resident, Thomas Jefferson.

We parked the car in the garage and walked onto campus. Charlottesville is, above all, a college town, and that college is the University of Virginia. This university was founded by Thomas Jefferson himself, in 1819, and the place still bears his distinct thumbprint. Jefferson designed the buildings—now a UNESCO World Heritage site—and designed the curriculum and sat on the original Board of Visitors. Indeed, the university is arguably the most complete expression of Jefferson’s intellectual vision.

As it happened, we arrived in the university’s central building—the Rotunda—right at the commencement of a free guided tour. Naturally, our guide told us a little bit about this building first. A dedicated Neoclassicist, Jefferson modeled his design after the Parthenon, as well as works by the Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio. But Jefferson’s use of red brick gives the building a distinctly American stamp. Just as significant as the building’s form is its function: it housed the original university library. This is an obvious and significant deviation from the traditional, medieval model of a university, centered on a church. Indeed, Jefferson’s plan was so insistently secular that he did not even want theology or divinity taught to his pupils. This elegant building was severely damaged by a fire in 1895, during which a group of enterprising students saved a marvelous life-sized statue of Jefferson by pushing it onto a table and carrying it out together. Jefferson’s spirit would have thanked them if he had believed in the afterlife.

Extending outward from both sides of the Rotunda, like two arms, are the parallel rows of buildings that enclose the Lawn. These are the ten Pavilions (five per side), where faculty reside and teach. Nowadays, professors only live in these Pavilions for three to five years, and rotate to allow for fresh faces; but in Jefferson’s original idea, the faculty would stay here long-term and live among the students. Even now, the resident faculty are expected to socialize with the students, 54 of whom stay (during their senior year) in the prestigious “Lawn rooms” that flank the Pavilions. On the other side of the Pavilions are gardens; and beyond that, the Range, for graduate students. The idea is both idealistic and charming: Jefferson imagines a kind of open-air community of scholars, living amid architecture that inspired the mind. Indeed, each of the ten Pavilions bears a distinct, Neoclassical design, the idea being that the ensemble would be a kind of visual catalogue of architectural styles.

On the whole, I found the Academical Village to be greatly appealing. I would love to wake up in one of those quaint little rooms, sit outside on my rocking chair, under the colonnade, reading some book, and waving casually to my passing professors. Few places I have been so perfectly evoke the gentile life of the mind—the elevation of beauty, truth, and goodness over all petty practical concerns. This picture contains a large dose of fantasy, unfortunately. The first batches of scholars were rowdy, spoiled, wealthy boys, who drank and partied and played pranks on their professors. More significantly, it is worth remembering that these buildings, gardens, and manicured lawn—not to mention the entire economical system—was built by slave labor. And though students could not bring their own slaves, professors could and did. To the rosy image of intellectual freedom, then, we must add the violence of human bondage.

Just as our tour of the university was coming to a close, our tour of Monticello, Jefferson’s old plantation, was about to begin. Now, Monticello literally means “little mountain,” and the name is perfectly sensible, as the house stands on a hill overlooking the surrounding area. We drove up to the visitor’s center (which has a café and a gift shop), and then hopped on the shuttle bus up to the house for our tour. Monticello can only be visited on a guided tour, which took around two hours. No photos are allowed inside, but the website includes a wonderful virtual tour, which is far better than this measly blog post.

I will hardly bother to describe the exterior of Monticello, since if you have seen a nickel you know what it looks like. Suffice to say that it is built in the same Neoclassical style, with the same red brick, as the buildings of the university. Indeed, Monticello could be transported to the center of the University of Virginia and look perfectly at home.

The house is entered, logically enough, through the front door, which leads directly into the entrance hall. This room is decorated with all sorts of artifacts from Lewis and Clarke’s epochal journey into the American wilderness—horns, antlers, Native American artifacts, and even the mandible of a mastodon. (According to Meacham, Jefferson’s attitude towards Native Americans was only slightly more enlightened than his contemporaries, thinking them not racially but culturally inferior. In any case, he still had no qualms about taking their land.) There are also many busts on the wall—including one of Voltaire, and another of Jefferson’s rival and nemesis, Alexander Hamilton. I suppose Jefferson liked his enemies close.

Most conspicuous of all might be Jefferson’s Great Clock. It has two faces, one facing outward, which only shows the hour (accurate enough for slaves, Jefferson thought), and another facing inward, with a minute and a second hand. It is quite a contraption. The clock is connected to a gong outside, which chimes out the hour loud enough for the whole plantation to hear. It works via a series of weights, which look like cannon balls. The clock is wound up at the beginning of the week (Sunday), and the falling weights mark the day as well as keep the hour. Unfortunately, the clock was designed for a somewhat more ample space, and so the last day of the week (Saturday) is located in the basement.

As one moves through Monticello, the visitor gets a greatly paradoxical impression of Jefferson. He was, for example, both provincial and cosmopolitan. Not remarkably well-traveled himself, he read voraciously about other lands (such as in the journals of Captain James Cook), and kept up a correspondence with contemporary explorers like Alexander von Humboldt and Meriweather Lewis. On the other hand, he was himself something of a homebody, keeping close to Monticello (after his return from France) and even founding his pet university in his backyard. In terms of taste, Jefferson improbably wants to combine a kind of rural simplicity with an enormous mansion and French style, making the house seem both luxurious and homely.

Another contradiction is between Jefferson’s genius and his dilettantism. His library spans dozens of academic disciplines, and yet his manner of organizing books, plants, and correspondence is entirely homespun. Monticello is a work of architectural brilliance; but the windows awkwardly span both the first and the second floor, meaning that they do not align with eye level. The clock may epitomize this contradiction best: an ingenious device for which Jefferson had to bore a hole through his own floor. The biggest contradiction of all, of course, is that the self-proclaimed champion of freedom lived in a slave plantation. But I will return to that.

From the entrance hall, the visitor quickly moves to Jefferson’s living quarters. His working life centers upon his library and his “cabinet” (or, study), which are filled with dusty volumes, the busts of famous men (like his frenemy, John Adams), and scientific instruments, such as his telescope, barometer, or theodolite (a surveying instrument). Both rooms overlook Jefferson’s greenhouse, where he grew exotic plants. The quaint quality of Jefferson’s mind is quite apparent here. He had a five-sided writing stand commissioned and built, so that he could display different documents and books (though a simple table seems more practical to me). On his desk stands a bygone innovation, the polygraph, which uses a mechanical arm holding a pen in order to duplicate letters (and Jefferson was a prolific correspondent). Jefferson did not invent the device, but he tinkered with it, and was quite enthusiastic about its use. The most idiosyncratic touch may be Jefferson’s bed, which is built into the wall between his study and bed chamber. The arrangement does save space; though for a man of 6’2’’, the bed seems quite snug.

My favorite room in the house was perhaps the parlor, where Jefferson did much of his entertaining. The room has a high ceiling and an unusual geometry. Opposite the main doors (hooked up, under the floor, so that both sides open and close in tandem), there are two pairs of tall windows and a single glass door, all looking out at the back garden, which serve to make the room sunny and bright. Two pianos and a zittern (similar to a lute) sit ready for music-making; Jefferson himself took part on the violin. Most attractive, for me, were the many portraits covering the walls. A somewhat unusual painting of George Washington stands near the famous Mather Brown portraits of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, made while the two men were overseas, with Jefferson looking distinctly more foppish than usual in his big white wig. On another wall hang three portraits of Jefferson’s intellectual heroes: Francis Bacon, John Locke, and Isaac Newton—all unabashed champions of empiricism.

I do not wish to get bogged down in a room-by-room description of Monticello, but I must mention some highlights. One of Jefferson’s innovations were double windows, which let in light but provide for more insulation, since the air between the glass acts as a buffer. The dining room is equipped with a dumbwaiter to bring up wine from the cellar (Jefferson liked French wine), to minimize the number of servants (read “slaves”) needed for his guests. An octagonal bedroom on the ground floor—with another alcove bed—is called the “Madison room,” since this was where that other founding father stayed on his frequent visits. Upstairs (and the stairs are very steep and narrow, another oddity of Jefferson’s design) there are mainly bedrooms, for Jefferson’s sister, daughter, and grandchildren. The tour culminates with the dome room—also octagonal, as apparently Jefferson loved the shape—on the third floor, which provides a commanding view of the surrounding area.

But now we must leave the house of Monticello itself, and explore the grounds of the estate. For here is where the history of Monticello becomes decidedly less charming. Monticello was not simply a residence, but a plantation, wherein enslaved men and women worked to enrich Jefferson. This was done by growing and selling crops—tobacco and wheat, notably—as well as by producing goods for sale, such as nails. On the road running past the house, dubbed Mulberry Row, stood the small residences of these enslaved workers, many of whom labored alongside white contract laborers to construct the house. Some of these still stand, or have been reconstructed. One of the latter is the cabin of John Hemmings, a literate carpenter who was one of the few enslaved people to be freed by Jefferson.

The contrast between elegant finery of the mansion, and this simple little dwelling, is almost gut-wrenching. That the man who declared that liberty was an inalienable right, that all men were created equal, could own fellow human beings and live by the violent coercion of their labor—it is simply too paradoxical to swallow. One naturally at least hopes that Jefferson was an especially “good” or “enlightened” slave-owner, whatever that would mean. But even that is not the case. Jefferson owned 600 different people during the course of his life—about 100 at any one time—and he treated them much as his neighbors did: namely, by giving them the choice between work or physical punishment. Husbands and wives were separated, as were mothers and children; and Jefferson ordered his overseers to beat enslaved people on multiple occasions. This should hardly need stating: Slavery requires violence to exist, and is itself a form of violence. There is no nice way to own a person.

One cannot even take comfort in the fact that Jefferson was distant from the real management of his estate, like some dreamy philosopher absorbed in his pursuits. Slavery was at the core of his life. After his wife passed away, Jefferson began a sexual relationship with his wife’s half-sister, an enslaved woman named Sally Hemings. Indeed, this “relationship”—if that is what it should be called—likely began when Hemings was still an adolescent. And while we do not have much notion of how the young Hemings felt, it is difficult to call such sex “consensual,” considering that Jefferson was much older, not to mention her legal owner, as well as the owner of much of her family. Sally Hemings had six children by Jefferson, whom he owned until his death, freeing them in his will. Evidently, slavery could not have been a more intimate part of Jefferson’s life.

The tour ends with a walk down back to the visitor’s center. On the way, you pass by the Monticello Graveyard, where Jefferson himself is buried along with many members of his family. His own tombstone—tall, but not grandiose—bears an epitaph he wrote himself, mentioning three accomplishments: that he wrote the Declaration of Independence and the Statue of Virginia for Religious Freedom, and that he founded the University of Virginia. Anyone familiar with his life will immediately notice that it omits arguably his greatest accomplishment: serving as President. But Jefferson was very mindful of his image, and strove hard to preserve his aura of the humble, unworldly intellectual; and so I think the epitaph is very much in keeping with this persona.

Further on, down near the parking lot, is a fenced off area. This was a burying ground where at least 40 of the enslaved people of Monticello were buried, though you would never know it if not for the sign, as there is not a tombstone to be seen. Once again, the contrast speaks for itself.

Though Jefferson is buried on the property, his family soon lost it after his death. For all of his brilliance as an intellectual and a politician, Jefferson was not a good businessman, and died hopelessly in debt. The house—including the vast majority of the enslaved workers—was sold after his death to pay off these debts. Luckily for posterity, the property was bought by an admirer of Jefferson, Uriah P. Levy, who preserved the house. Monticello is now owned and run by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which I think does an excellent job in telling the story of this place. Every aspect of this complex man—from his scientific pursuits to the reality of slavery—was explained with honesty and care.

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation does not attempt to resolve the conflicts inherent in the life and legacy of the third president. Nor will I. Indeed, there is no way to resolve the paradox: Jefferson was a champion of freedom and a slave-owner. He was a man of life-enhancing brilliance who participated in one of history’s most monstrous institutions. His words epitomized some of our finest aspirations, while his actions embodied our basest impulses. I do not think penning the Declaration of Independence can somehow cancel out the violence inflicted on 600 human beings. Morality does not work like that. If he were brought back from the dead, we would have to award him the Nobel Prize and then throw him in prison for the rest of his life.

For this reason, we left Monticello just as appalled as inspired by Thomas Jefferson’s life. His legacy is perhaps most valuable, then, as a reminder that high ideals on paper can and do coexist with ugly realities in the world. This, after all, is just as true of the story of America as it is that of Jefferson. We should not make the same mistake as Jefferson in thinking that we can politely express our disapproval of an oppressive and unsustainable system while profiting by it and doing nothing to change it. Even now, almost two centuries after Jefferson’s death, there is still much work to be done.

2021: New Year’s Resolutions

Needless to say, 2020 was not an ideal year to be accomplishing goals out in the real world. But in my blog world, it was not so bad. I read a lot of good books, wrote a fair bit, and even succeeding in publishing a short story. Best of all, my novel is set to be released in February!

Even though I did not do much traveling this year, I still have a fair backlog of destinations to cover. Here’s the short list:

- Andalucía

- Asturias

- Auschwitz

- Istanbul

- Krakow

- Las Médulas

- Monticello and the University of Virginia

- Naples and Pompeii

Aside from this, my major goal of 2021 is to finish at least a couple drafts of the novel I am currently working on, with maybe a few short stories thrown in. In an ideal world, I will also finally wrap up Don Bigote and continue with my Quotes & Commentary, two long-stalled projects.

Apart from that, I am grateful simply to have survived intact. My social life got narrower but deeper. I did not exercise as much as I wanted to, but I did improve as a cook. I learned a great deal, though not what I planned to learn. There are now so many books I want to read—about history, science, math, politics, music, art—that I cannot even make a list. But I have come to the conclusion that one must always have too many books to realistically read. Life is too dreadful otherwise.

With a new man (and woman) in the White House, and several effective vaccines, I am optimistic about this coming year. Cheers to that!