This is part of a series on Historic Hudson Homes. For the other posts, see below:

- Washington Irving’s Sunnyside

- John D. Rockefeller’s Kykuit

- Alexander Hamilton’s Grange

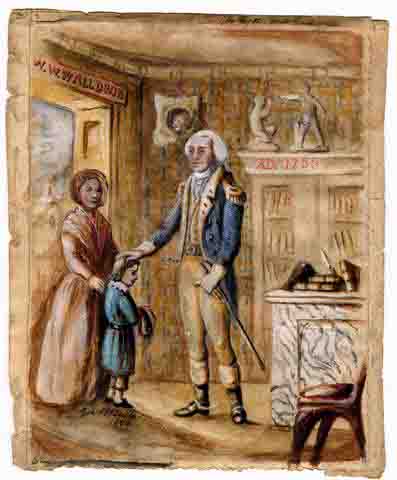

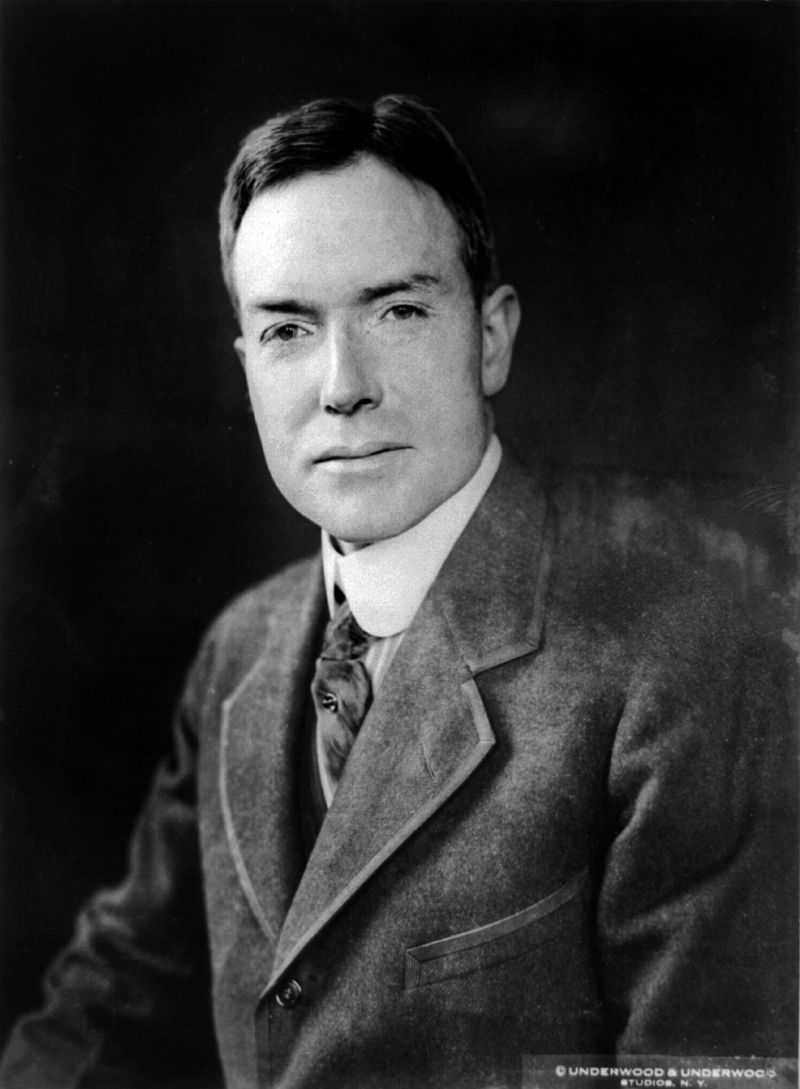

By common consent, the richest man in modern history was John D. Rockefeller. At his peak he was worth at least three times more than the world’s current richest man, Jeff Bezos—over $300 billion to Bezos’s $112 billion. In a world before income taxes or antitrust laws, it was possible to amass fortunes which (one hopes) would be impossible today. Strangely, however, this living embodiment of Mammon did not have extravagant tastes. To the contrary, for a man of such unlimited resources Rockefeller was known for his simple, even puritanical, ways. According to Ron Chernow, a recent biographer, Rockefeller had a habit of buying homes and keeping the original decoration, even if it was absurdly out of keeping with his own taste, just to avoid an unnecessary expense.

Thus when John decided to buy a property near his brother William’s estate (Rockwood), near the Hudson River, he simply stayed in the pre-existing houses. (William’s Rockwood mansion has since been torn down, but the property has been transformed into a wonderful park.) The spot Rockefeller chose occupies the highest point in the Pocantico Hills overlooking the Hudson; it is named Kykuit from the Dutch word kijkuit, which means “lookout.” Likely enough Rockefeller would have been satisfied indefinitely with a fairly modest dwelling, had not his loyal son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., decided to take charge of a manor house to be built for his father.

Junior and his wife, Abby Aldrich, set to work on an ambitious, architecturally eclectic design. They worried about every detail, as they knew how exacting and finicky the paterfamilias could be; the planning and construction took six painstaking years; the couple even took the precaution of sleeping in every room in the house, just to be sure that it was perfect. Nevertheless, John the father was unsatisfied; and he could not conceal his dissatisfaction. He was disturbed, for example, that the servants’ door was right underneath his bedroom window, so he could hear it clapping all day. Eventually (and doubtless to his son’s dismay) Rockefeller concluded that the house needed to be completely remodeled; and thus the current, Classical Revival form of the house came into being.

(An amateur landscape designer, Rockefeller was also dissatisfied with the work of Frederick Law Olmsted, whom you may remember as the designer of Central Park. Senior decided to do the landscaping himself.)

As in Sunnyside, tours are given by the Historic Hudson Valley. But you cannot go directly to the Kykuit property. To visit, you must buy a ticket in the gift shop of Philipsburg Manor, another historic site (a 17th century farm) in Sleepy Hollow, right across from the Cemetery. After you sign up for a tour, you board a small bus, which transports you on the 10 minute ride to the property. A cheesy informational audio clip plays during the trip, giving some brief background information about the family and the property. This sets the scene for the tour guide. I have, incidentally, heard that the content of the tour can vary significantly depending on the guide’s interests.

As the bus rolls in, through the gates and beyond the walls—passing by a “play house” still used by the Rockefeller family (many of whom still live somewhere on the massive estate)—one gets a sense of the private, exclusive, and isolated world inhabited by the world’s richest man. Widely known and, for a time, almost universally hated, Rockefeller needed to create his own refuge. My favorite detail was the tunnel underneath the mansion that was used to make deliveries without disturbing Rockefeller’s rest.

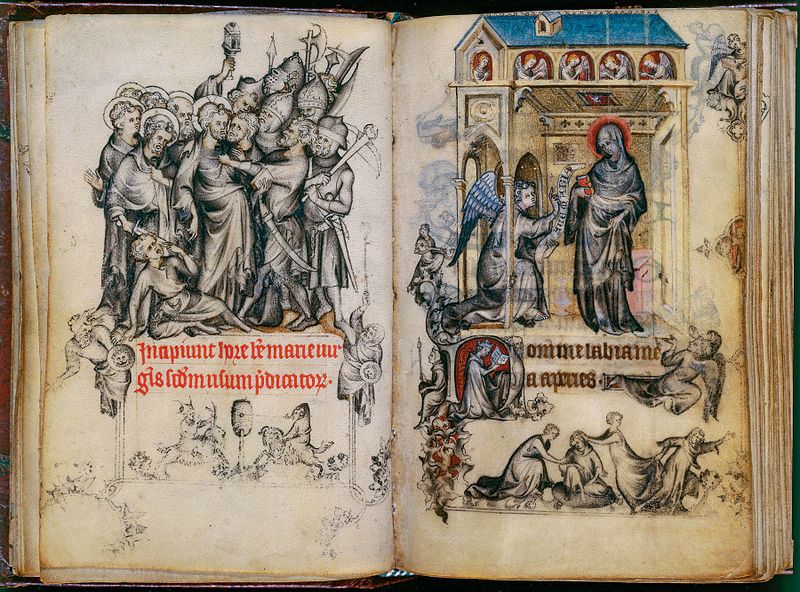

The bus deposited us in front of the house, near an impressive Oceanus fountain, copied from a fountain in Florence. Ivy crawls up the stone facade, all the way up to the neoclassical tympanum. An eagle crowns the top, displaying the family crest. From there the guide led us up onto the porch, where two strikingly modern statues stand flank the doorway. This is a constant feature in Kykuit: the juxtaposition between classic and contemporary tastes. John D. Rockefeller himself had very little taste in art, conservative or otherwise; his son, Junior, was enamored of the past—Greek, Medieval, even classical Chinese. Meanwhile, Junior’s wife, Abby, and his son, Nelson, were important patrons of modern art. Thus the house is an, at times, uneasy incorporation of these divergent tastes.

As a case in point, there are beautiful examples of Chinese porcelain on display throughout the house, protected by plexiglass cases. (The guide explained the glass was installed to protect them from playing children.) In a room used by Nelson Rockefeller there is also the vice-presidential flag, commemorating his term under Gerald Ford. Nelson wanted to be president himself, and he had the experience to do it—he was the governor of New york from 1959-72—but according to Ron Chernow, his divorce made him an unpalatable candidate. (How times have changed!) There were also portraits of the Rockefellers, and a phenomenal bust of the bald, decrepit, and yet mesmerizing John D. Rockefeller Senior—whom I was excited to meet, since I had just read a book about him.

After this, our guide led us into the gardens. The most notable feature of these are the modernist statues scattered about—gruesome metal bodies amid neat hedgerows. Unsurprising for such a commanding spot, the view is excellent. On a tolerably clear day you can see all the way to Manhattan from the back porch. I imagined lounging on an easy chair, sipping some very posh drink—for some reason a mint julep comes to mind—and contemplating the Hudson. But of course the Rockefellers were Baptist stock, and teetotallers all, so the drink is pure fantasy. Beyond view (and beyond the scope of the tour) was the reversible nine-hole golf course that Rockefeller used with Baptist scrupulousness; after God and Mammon, golf was his top priority. Likely Rockefeller Senior would have been shocked and appalled by the massive modernist statue (resembling an alien squid) that was airdropped by helicopter into place on the property during his grandson’s tenure.

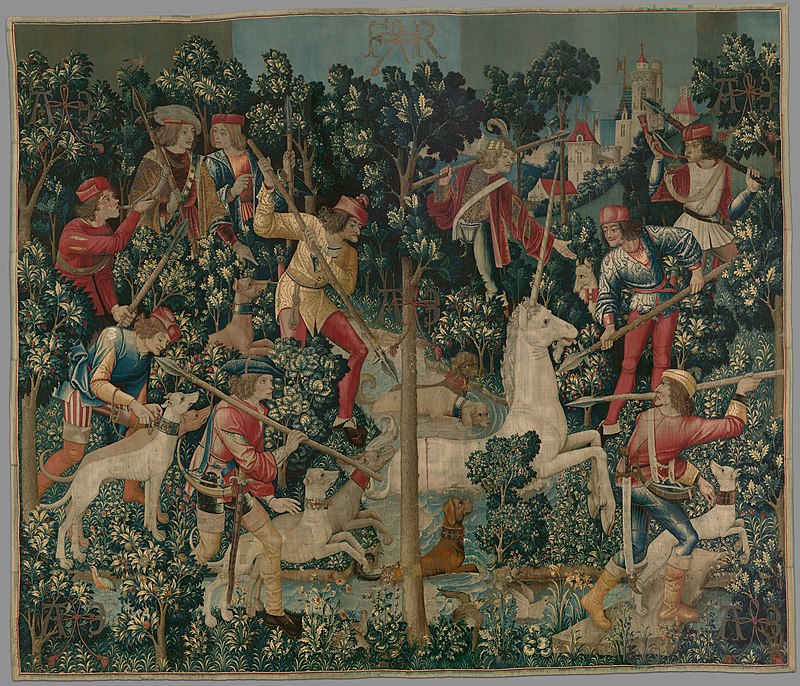

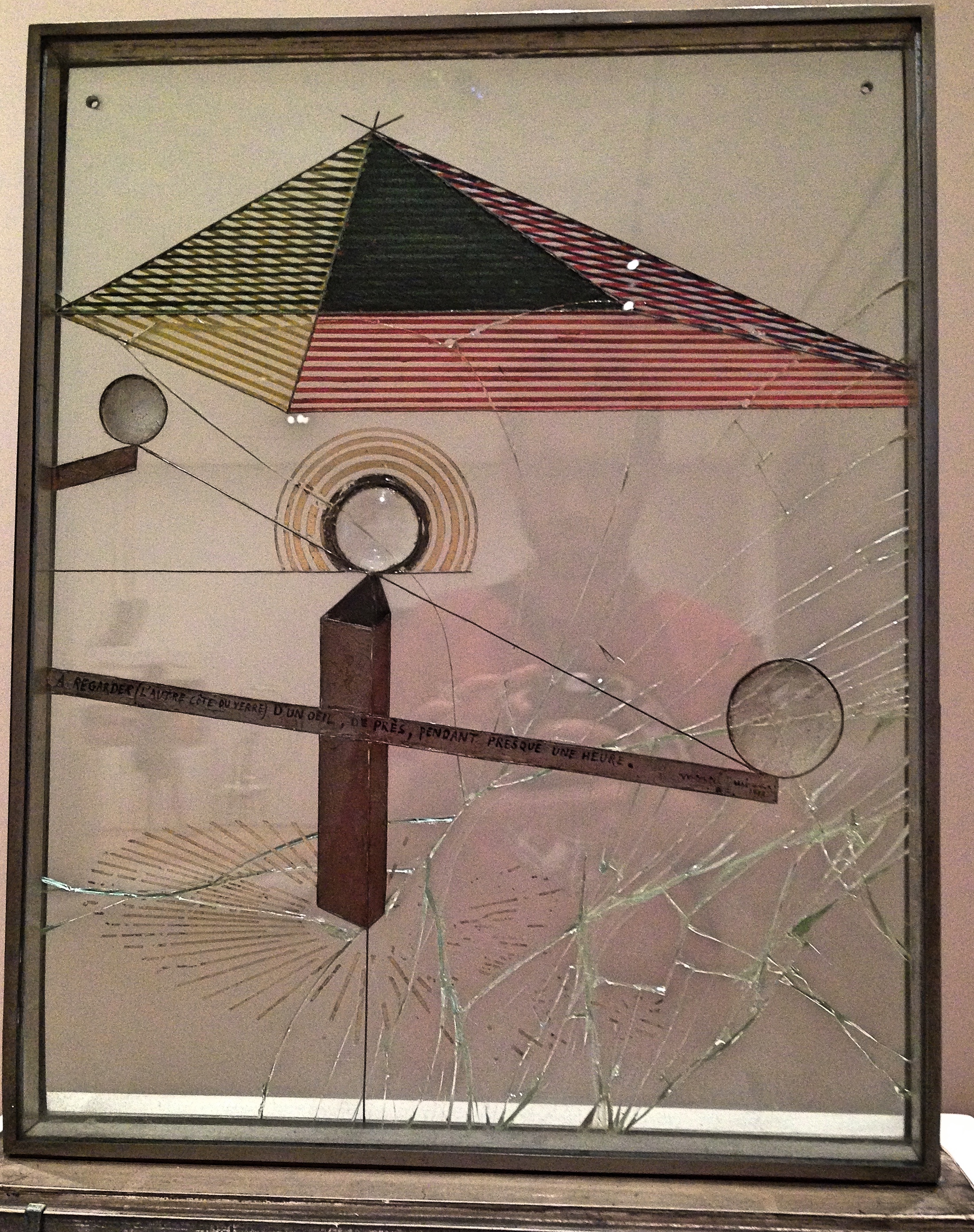

Then we made our way inside to visit the art gallery in the basement. This includes original works by many modern artist, the most famous being Andy Warhol; but the best works on display are undoubtedly the Picasso tapestries. These were commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller, to be made by Madame de la Baume Dürrbach, for the purpose of making his works easier to display. The biggest of these tapestries was a copy of Guernica, now on display at the United Nations building. Of the ones in this private gallery, my favorite is of Picasso’s Three Musicians (the original hangs in the MoMA). Even when I toured Kykuit as a child, tired, hungry, and very bored with all this old-people nonsense, I was impressed that a person could have Picassos in his basement; and my opinion has not changed.

To speed through the tour somewhat, we eventually boarded the bus again to go back to Philipsburg Manor. However, we did stop at the stables on the way back, which was filled with antique horse carriages and old luxury automobiles. In addition to being an avid golfer, you see, Rockefeller Senior also loved to go riding in his carriage and, in later life, to take fast drives in his fancy cars. (A strange detail from the biography is that, in later life, the upright and conservative Rockefeller would grope women during these rides. He was a man of many contradictions.)

This fairly well sums up my visit to Kykuit. It is an impressive place—six floors, forty rooms, and twenty bedrooms. Even so, considering Rockefeller’s vast fortune, and considering the kinds of monstrous mansions that other rich families—most notoriously the Vanderbilts—built for themselves, it is a restrained edifice. One can see the old Baptist tastes coming through, even amid all this wealth and splendor. Even so, I cannot imagine living in such a private world, so far removed from pesky neighbors and city noise. But the Rockefellers apparently had no trouble with the house. Nelson Rockefeller lived in it up until his death in 1979, when it was donated for use as a museum.

Before ending this post, I should also mention two nearby Rockefeller monuments.

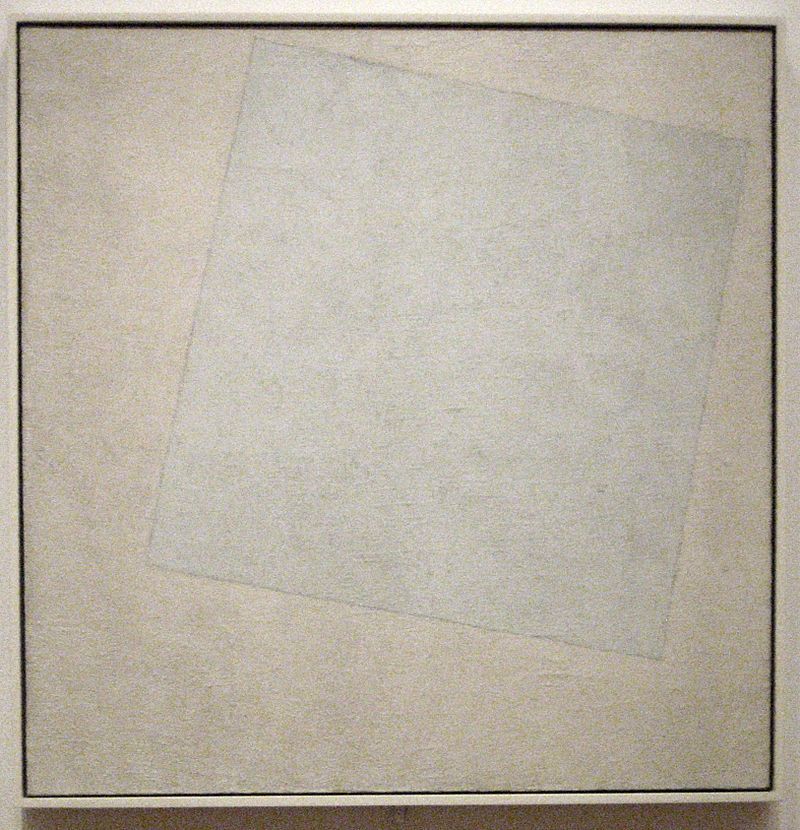

The first is the Union Church. This is one of two non-denominational churches (the other being Riverside Church in Manhattan) commissioned by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. It is an attractive and modest building, made of cut stone with a steeply slanting roof. Though the church does have an active congregation, most of the time its main use is as a tourist attraction, also administered by Historic Hudson Valley. The church is notable for its stained glass. The rose window was designed by the modernist pioneer Henri Matisse; according to the guide (I was the only one on the “tour”), it was the last work the artist ever completed. It is a simple, abstract pattern, yet subtly interesting to look at. More memorable, however, is the series of stained-glass windows completed by Marc Chagall, using Biblical scenes to commemorate deceased members of the Rockefeller family. Though I am normally not greatly fond of Chagall’s work, I must say that the strong, simple colors of Chagall’s windows created a pleasant—if not exactly religious—atmosphere.

The second Rockefeller institution is Stone Barns, a center for sustainable agriculture established by David Rockefeller (Junior’s youngest son). (Sharing the Rockefeller talent for long life, David passed away just last year, at the age of 101.) The center lies on the edge of the Rockefeller State Park, alongside Bedford Road, surrounded on all sides by rolling farmland. It is a very pleasant place for a stroll. The buildings of the complex are completed in a style reminiscent of Union Church, as well as of the Cloisters museum in Manhattan: deep-grey cut stone. The farm is dedicated to growing high-quality produce and livestock without using anything “artificial.” Some of its products are served in the famous Blue Hill restaurant on the property—a place so absurdly fancy and expensive that, judging by the way things are going, I doubt I will ever get an opportunity to try. The menu, which costs $258 per person, consists of many different courses of artisanal dishes using esoteric ingredients. I have bought cheaper transatlantic plane tickets.