The Corner: A Year in the Life of an Inner-City Neighborhood by David Simon

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Some authors have the power to make you feel that you are just understanding the world for the first time. This is, for example, Roberto Caro’s gift. In every one of his books, he seems to expose the world of politics, revealing its inner workings like an ant colony on display in a transparent container. And this is also the consummate gift of this writing team, Simon and Burns. Here, as in Simon’s Homicide, and as in their masterpiece The Wire, these authors show you something you think you already know about: urban poverty. But you really see it for the first time.

In many ways, this book is the ideal companion to William Julius Wilson’s book, When Work Disappears, which was published just one year earlier. Wilson, a sociologist, explains urban poverty using historical trends, statistics, and surveys, whereas Simon and Burns worked like anthropologists: following around their subjects for an entire year and more, trying to understand their world through their eyes.

These different methodologies converge on the same story. When decent working-class jobs disappear from an area, it sets off a chain reaction that erodes the fabric of the society. Those with means move out; those that remain behind are left with few and stark choices. The teenagers in this story, for example, are faced with the options of attending a struggling school system, working for a minimum-wage job, or selling drugs. And while there are significant risks to this last option—risks that, sooner or later, become terrible consequences for all of them—it is undeniable that the reward is immediate and great.

Another theme of both books is how strategies and mindsets that are adaptive on “the corner” are maladaptive anywhere else. The tendency to think in the short-term, to backstab, to lie and cheat, to never show vulnerability—all of these are essential for both the addicts and dealers, though of course they become self-defeating when any of them try to leave this world. And of course many do try to leave it, earnestly and repeatedly. But with so few economic opportunities and so many barriers to government aid (the struggle to just get into a rehab center is Sisyphean), these efforts meet with scant success.

When writing of people in such difficult circumstances, it is tempting to treat them as pure victims. Yet the authors manage to convey the full humanity of their subjects—their many shortcomings and also their strivings—while never minimizing what they are up against. Indeed, this is perhaps the most impressive aspect of this book, and what makes these stories so compelling simply as stories, and not just illustrations of American decadence.

If there is any moral to this book, it is the absolute failure of the war on drugs. Simon and Burns tell of an unending, unceasing drug market—an entire ecosystem of sellers and buyers, operating 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, right in the open. Yes, the police do come and make arrests and confiscate a few vials. But the risk of incarceration is nothing compared to the force of full-fledged addiction or the endless, easy money that dealing provides. At one point, the authors aptly compare the drug war to the debacle of the Vietnam War: all the money, manpower, and machinery in the world is not enough when a war is ill-conceived to begin with.

But what is the solution? What would help? The authors—wisely, I think—refrain from any policy suggestions. Instead, we are left with a kind of mirror-image of the America that Robert Caro describes. Whereas Caro focuses on extraordinary individuals who fundamentally change their worlds, Simon and Burns show how political inertia, economic forces, and human folly conspire to trap everyone—inner-city teachers, beat cops, social workers, rehab nurses, and everyone selling and using—in an endless cycle that chews people up and spits them out, generation after generation. As in Homicide, this is a remarkable work of journalism.

View all my reviews

Month: August 2023

Review: Homicide

Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets by David Simon

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

What led me here (as I suspect is true of many readers) was my love of The Wire. Of all of the television I have seen, I found Simon’s masterpiece to be uniquely engrossing and thought-provoking. And despite the obvious creative license taken with the plot, what makes the show so compelling is the bedrock foundation of fact upon which the story is based. Thus, I wanted to get to know some of Simon’s source material directly.

I am glad I did. This book is a triumph in its own right—worth reading even if Simon had never gone on to be a famous television writer. This is just an excellent work of journalism. Simon was given unique access to a squad of murder detectives and their work. He hung around the office on late nights, he listened to interrogations, he read case files, he visited murder scenes, he sat through trials, he went to hospitals and morgues—in short, he did it all. And by simply organizing his observations and writing them down, he has produced a wonderfully insightful look into crime and police work.

Anyone with even a passing acquaintance with detective stories—that is, all of us—has internalized quite a few myths and preconceptions, which are battered to pieces in these pages. For one, most murders do not have a motive beyond rage, greed, or simple recklessness. They are purely impulsive, so detectives rarely bother asking “Who would want this person dead?” Indeed, the Sherlock Holmes image of the cold, rational detective motivated by his love of the common good has virtually no shred of truth to it. The detectives in this book, while decent men (and they are all men), are not on a personal mission against crime. They are motivated by professional pride, by departmental statistics, by overtime pay—and occasionally, yes, by strong feelings of justice.

While we often hear stories of cold cases being solved through innovative scientific techniques, the basic tools of the detective are quite simple: evidence, witnesses, and confessions. And the first two are usually necessary to obtain the third, since most people don’t confess unless they’re backed into a corner. The interrogation techniques Simon describes are somewhat disturbing. Though the detectives do make their suspects aware of their Miranda rights, they do so in such a way that suspects are too intimidated or confused to really stop and consider their next move. The majority don’t use their right to call a lawyer, and instead endure hours of intense interrogation, while detectives browbeat and sometimes scream at them. A surprising number of suspects break and sign confessions.

It is hard not to feel uneasy about this. Indeed, studies have found that some innocent people will even confess to crimes they didn’t commit, just to escape from the intense psychological pressure of the situation. But Simon makes the point that, if detectives were prevented from using manipulative interrogation techniques, they would hardly convict anyone. And when he details the difficulties of actually convicting murderers in court (far fewer than 50% of those arrested for murder end up convicted by a jury of their peers), it is difficult to resist his logic. And when the top brass demand a high clearance rate for the department (that is, the rate of solved to unsolved murders), it is no wonder that detectives will resort to anything to put a case from red to black.

As is usual with Simon’s work, this is the story of ordinary, fallible people who are doing their best (mostly) in a failing, dysfunctional system. The reasons that there are so many murders in Baltimore in the first place go very far beyond the walls of the police department or even the city government. So even though the detectives often do admirable work and lock up obviously dangerous individuals, there is an overwhelming sense of futility in the book. After all, the detectives only arrive after a murder has taken place. They may find the man responsible (and it is usually a man), but even with him behind bars, the next murder is just a block, or a day, or a phone call away.

Yet the book is not wholly bleak. What prevents it from being so are the personalities of the detectives. For the most part, they are smart and, often, surprisingly funny—with a dark gallows humor imposed by the job. And they are surprisingly sympathetic. Indeed, although I share very little life experience with any of these men, somehow I often found myself identifying with them. This is, in essence, the charm of the book: rather than making you fantasize about being an investigative genius, it allows you to see what it would be like if you—the real you, but in another life, perhaps—became an actual, overworked, underpaid homicide detective.

It is a rare book that dramatizes police work while neither elevating the detectives into superheroes nor demonizing them as thugs. Like a good candid photograph, Simon’s portrait is both unflattering and endearing. It is both an uncommonly good work of journalism and a work of art.

View all my reviews

Budapest or Bust

I have never met a person who has traveled to Budapest and didn’t like it. Though the city was not even on my travel radar when I arrived in Europe—not featuring prominently in any of the history I was familiar with—one glowing review after another was enough to convince me to pay the city a visit. “Not every city has a vibe,” one of my friends told me one day. “Budapest definitely has a vibe.”

I arrived in Budapest one day in early April, fully ready to be vibed (or whatever the verb might be). A variety of things immediately pleased me: the plentiful restaurants (I ate Chinese noodle soup), the convenient trams and buses, and the well-designed transport app that allowed me to buy every ticket I needed on my phone. And all of it was cheap! Perhaps I am overly attached to lucre, but when I am in a reasonably-priced place I feel immediately better than when I am somewhere expensive. Rather than having to guard my wallet with my life—which means continually fighting my impulses to do pleasurable things—I can relax and simply enjoy the experience. I was, in short, already vibing.

After my bags were dropped off, I first headed to the Hungarian National Museum. This actually wasn’t in my original plans, but by chance it was very close to my Airbnb, so I figured: why not? It was a good choice. The Hungarian National Museum covers the history of the country from prehistory to the present. It is a story that I was hardly acquainted with. To simplify matters greatly, one theme in Hungarian history is the preservation of their very distinct identity in the face of foreign domination and in spite of being at a natural crossroads between Europe and Asia. Hungary was a part of the Roman Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Third Reich, and the Soviet Union; and yet their culture remains highly distinct.

For example, the Hungarian language is, as you may know, unrelated to its Slavic or Germanic neighbors. Indeed, it is not even in the same Indo-European language tree that includes everything from English to Sanskrit—meaning that the Hungarians resisted even prehistoric invasions and expansions. Hungarian is, rather, a Uralic language, which means that it is more closely related to Finnish than it is to Russian. This is why it looks so strange to foreign visitors. I did not manage to pick up a single Hungarian word.

(I should also mention that the name for Hungary has nothing to do with appetite, but rather is a latinized form of an old Byzantine Greek name for the area. The Hungarians, for their part, call their country Magyarorszag, or “Land of the Magyars.” Their language is called “Uralic” because it is believed that the Magyars originated in the Urals, in present-day Russia.)

In any case, it was a wonderful museum, with Roman ruins in the basement, archaeological treasures on the ground floor (including an elongated skull), and beautiful medieval artwork on the top floor. One of the gems of the museum is a piano that once belonged to Beethoven and Hungarian virtuoso, Franz Liszt. And I was particularly gratified to learn the story of the American general, Harry Hill Bandholtz, who personally prevented Romanian forces from looting the museum in the aftermath of the First World War. The exhibit ends with the Soviet period; you walk out saying goodbye to Stalin.

After this, I was rather hungry (pun unintended but unavoidable), so I made my way to the Great Market Hall. This is exactly what it sounds like: an enormous food market in the center of the city. Opened in 1897, it was the brainchild of the first mayor of Budapest, Károly Kammermayer, and it was designed with flair. An enormous steel structure, it is big enough to be an airport hanger, and almost attractive enough to be a church. The roof is covered in colorful tiles, much like the Cathedral of Vienna, and the inside is full of all sorts of decorative touches in its steelwork. Like the Eiffel Tower, completed just ten years earlier, this is a monument of the industrial age.

It is also just a fun place to be. The basement is stinky: full of pickled products and fishmongers. The ground floor has fruit and vegetable stands, wine for sale, butchers (with delicious Hungarian sausages), and lots of vendors selling Hungarian paprika. This spice is, of course, the culinary signature of the country, though you may be surprised to learn that it became popular in the country as recently as the 1800s. (The Spanish, by contrast, have been using it since the 1600s.) Hungarian paprika may not have the deepest historical roots, then, but its fame is justified by its deep flavor. You can trust me on this, since I bought some at the market, took it home, and cooked with it.

The best part of the market is the upper floor, which is full of lots of tourist junk and, much more importantly, restaurants. I stopped at one food stand selling Hungarian staples and got a plate of chicken paprikash with a side of nokedli (Hungarian dumplings). It was phenomenal—so phenomenal that I didn’t mind sitting on the floor (the seats were occupied) and eating it from a flimsy paper plate. I ought to mention that, the following day, I returned to this market and got a Hungarian sausage with potatoes, which was also scrumptious.

Now, a few paragraphs ago, perceptive readers may have noticed the oddity that Budapest had its first mayor in the late 19th century. Isn’t it a much older city? The explanation for this is simple. Budapest was officially created in 1873, when the cities of Buda and Pest (and Óbuda) were joined. There remain significant differences between the two formerly separate cities, however: Pest is older, more touristy, and very flat, whereas Buda—which sits across the Danube—is hillier, quieter, and more residential.

My next destination was right in the center of Budapest: St. Stephen’s Basilica. Compared to many of the grand churches of Europe, this one is rather young, having been completed in 1905. Yet even if it lacks the historical interest of some other buildings, it is still worth visiting for the beautifully decorated interior, which is illuminated with golden light. The basilica is named for the first king of Hungary, who was a pious Christian at a time when many of his fellow Hungarians were pagans. His mummified hand is preserved in an ornate reliquary; and the royal appendage has had, in the words of the placard, an “adventurous fate”—having been kept in Transylvania, Dubrovnik, Vienna, and “carried west” during the Second World War. Despite all this, the best part of visiting the basilica may be the view from the top.

The rest of my first day was uneventful. I walked around the city, ate some goulash and lángos (Hungarian fried bread), and tried some Hungarian wine (very nice). I needed to build up some strength for the morrow.

I woke up early the next day and got ready in a rush. I had booked a tour in the city’s most famous and iconic landmark: the Hungarian Parliament Building. Thankfully, with the help of the excellent trams, I arrived with time to spare, and so could take a moment to enjoy the small exhibit on the building’s architecture located on its northern side. This was a kind of tunnel filled with gargoyles and spires and other stone fragments used in the building. Seeing it all up close did help me realize just how much work went into the design of this monument.

Soon it was time for the tour, and I approached the building. Of course, I had seen it in photos, but its scale is only appreciable from up close. Indeed, it is so big that I almost missed my tour by simply not being able to find the entrance. (One of the guards helped me.) I had to run, but I made it.

I should mention that tours to the Parliament Building fill up fast, so it is worth booking them well in advance. In my case, I had to sign up for a Spanish tour since there weren’t any English ones available when I looked. Occasionally it pays to be bilingual.

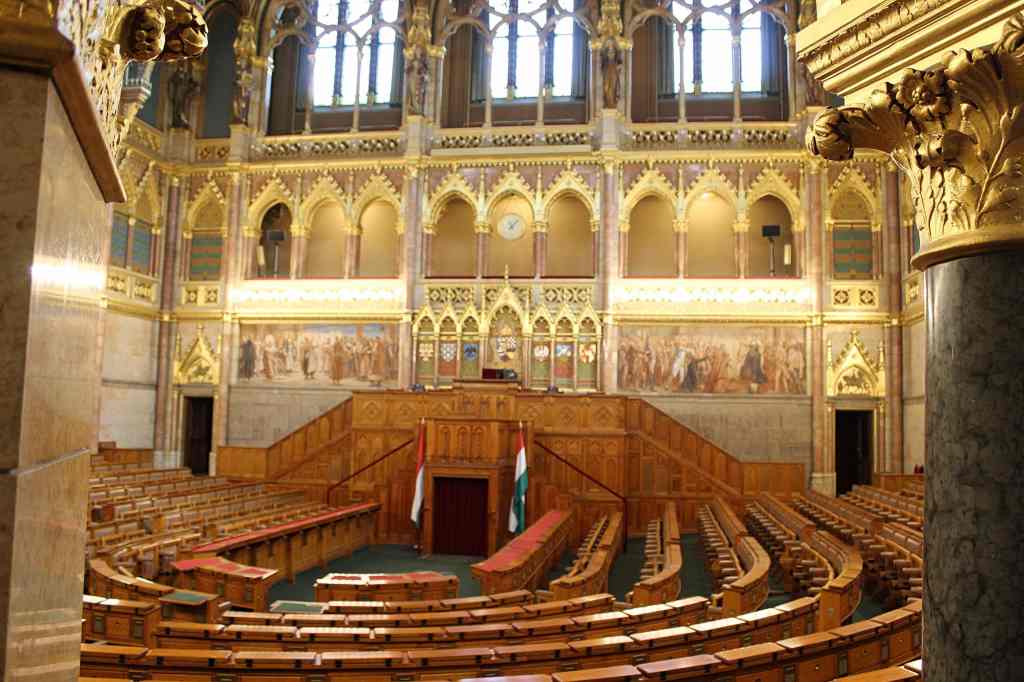

The tour lasted about an hour and took us through just a fraction of the building (it is, after all, the biggest building in the country). But it was a beautiful fraction. Built in 1902, the Hungarian Parliament Building is the soaring, majestic symbol of the country’s sovereignty and democracy. Every inch of it is ornately furnished, with gilded arches, stained-glass windows, and more statues than a cathedral. One highlight is the Assembly Hall, which must be among the most ostentatious settings for a legislative body in the world. The views are stunning, but I can imagine that it gets a little cramped with 199 Members of Parliament and their aides. Another showpiece of the building is the main staircase, which makes the entrances of royal palaces seem tiny by comparison. Right below the central dome is a glass case containing the Holy Crown of Hungary, which tradition states was first worn by St. Stephen himself. It may not be quite that old, but it is a beautiful example of Byzantine craftsmanship. Four liveried soldiers guard the crown, performing an elaborate changing of the guards ceremony every hour.

It is a great shame, to say the least, that a country with such a glorious temple of democracy should be experiencing a backsliding into autocracy under the presidency of Viktor Orbán. Indeed, the danger of dictatorship was starkly obvious during my visit, as it happened just a few months into Putin’s invasion of Ukraine (which shares a border with Hungary). In addition to myself, a Ukrainian mother and child were staying in the Airbnb, refugees of the war. On a lamppost I noticed a satirical sticker linking Orbán to Putin, and I wondered if Hungarians would heed the warning of this war.

Hungary certainly has had its fair share of tyranny. Examples are not far to seek. Right in front of the Hungarian Parliament is the Shoes on the Danube Bank memorial. This is a sculpture depicting just that: empty shoes, right on the edge of the river. This memorializes the Jews and other victims who were executed by the Arrow Cross party—the Hungarian equivalent of the Nazis, who took control of the country late in the war. Victims were first told to remove their shoes (potentially valuable) and then shot into the Danube.

Quite nearby is a less depressing monument, the Széchenyi Chain Bridge. This was the first bridge to permanently unite the Buda and Pest sides of the river. When it opened, in 1849 (for context, 34 years before the Brooklyn Bridge), it was considered a kind of marvel of engineering. More importantly for the tourist, the bridge has a lovely, classical design that forms an iconic part of the Danube panorama. Unfortunately for me, however, the bridge was completely closed when I visited. It had been closed since March of 2021, and is supposed to reopen sometime this year. The bridge is named, by the way, for a politician and reformer—revered by his fellow Hungarians for his progressive ideals—István Széchenyi.

But I am afraid I must return to the topic of tyranny, for my next visit was to the House of Terror. This is a building that was used by both the aforementioned Arrow Cross as well as the ÁVH (Államvédelmi Hatóság), the secret police of the communist regime. No photos are allowed inside, so memory will have to do. The entry came with an audio guide, which gave historical context to the photos and images on display. The story was familiar, if depressing: secret police “disappearing” political dissidents and enforcing the most stringent political orthodoxy. The visit culminated in a long, slow elevator ride to the lower level, which had been used as a prison where suspects were detained, tortured, and executed.

I next paid a visit to the Dohány Street Synagogue, more commonly called the Great Synagogue. Its name is due to its size as much as its beauty—it is the largest synagogue in Europe, with seating for about 3,000 worshipers. To visit, you take a guided tour; these are available in many languages and at frequent intervals. The architecture is rather peculiar, combining elements of European churches and Islamic decoration. Yet the synagogue’s history is more compelling than its design. During the Holocaust, the Jewish ghetto was right next to the synagogue; and as a result there is a cemetery for those who died in the brutal conditions. There is also an adjoined museum of Jewish culture, in the former house of Theodor Herzl, a famous activist and journalist, considered to be one of the fathers of Zionism.

The most moving part of the visit is to Raoul Wallenberg Memorial Park, which is on the site of the aforementioned cemetery. Wallenberg, I should mention, was a Swedish diplomat who managed to save thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Nazis (though ironically, he seems to have been killed by the Soviets). His name, and those of others who helped to rescue Jews from the Holocaust, are inscribed on leaves of a statue of a weeping willow designed by Imre Varga. Yet the vast majority of these leaves bear the names of the many thousands of victims of the Nazi terror. In total, over 400,000 Hungarian Jews were killed during the Holocaust, many of them at Auschwitz. Today, there are only about 10,000 Jewish people residing in the country.

(Though I did not manage to visit it myself, I wish I had gone to the Holocaust Memorial Museum while I was there. It was the first state-sponsored Holocaust museum in Europe, and is located in a former synagogue.)

This was a lot of heavy history for one day. So after a quick dinner, I was glad to have a triumphal finale in the Hungarian State Opera House. The building was opened in 1884, just a few years after the slightly more famous Wiener Staatsoper; and from the outside the two look almost identical. The inside is marvelous, as I discovered when I arrived for an evening performance of Richard Strauss’s Die Frau Ohne Schatten. I walked up the marble staircase, below the frescoed ceilings and gilded arches, to sit in my nose-bleed seat high above the stage. The view may not have been great, but I had only paid about $10 for my ticket and felt that it was an amazing deal, all things considered.

That particular opera is known as an extremely difficult work for its many soloists, complex music, and other pyrotechnics demanded by the mythological plot. Its performance was thus a testament to the skill of everyone involved. The particular opera is also quite long, so long that it had to be broken up by three intermissions. I highly recommend any visitors to Budapest to give opera a try, even if you don’t think you like the music. The combination of the fine architecture, elegant dresses, champagne during intermission, and of course the elaborate music, make for an oddly intense experience. Nevertheless, I should admit that I left during the third break, as I didn’t want to be there until midnight.

So far, everything I have described is more or less in the center of old Pest. But Budapest is a far-flung city, with things to see and do in many of its remote corners. This may sound like a negative, but with the city’s excellent public transportation system it is easy to get anywhere. This is why, I think, Budapest does not get as claustrophobically crowded as places like Prague or Munich, which have very focused centers of activity.

Now, to explain the next group of landmarks, you need to know a date: 1896. This is the year of the great Millennium Exhibition, a celebration of the 1000-year anniversary of Hungary. That is, in the year 896, a man named Árpád, leader of the Magyars, was made prince of the newly-created Principality of Hungary. Obviously, the Hungarians of the late 19th century had to celebrate their longevity, and to do so they staged an event similar to a World’s Fair.

Especially created for this event was the first metro on the European continent, and the third in the world (after London and Liverpool). This metro line is still in operation, known simply as Metro Line M1. It was made to ferry Hungarians to and from the fairgrounds. Unlike more modern metros, this one is extremely shallow, just a few feet below Andrássy Avenue, one of Budapest’s principal thoroughfares. The journey from street to metro is almost instantaneous. The metro is also a joy to ride, with attractive cars and stations along the way.

The line ends near Heroes’ Square, the centerpiece of the Millennium Exhibition celebrations. This is a big, open plaza with a sweeping assemblage of statues in two colonnades depicting (as you might expect) heroes from Hungary’s past. The square was obviously built to accommodate masses of people, though for the solo traveler it is almost annoyingly vast. Right in the center is the Memorial Stone of Heroes (often mistaken for a tomb of the unknown soldier), which is a monument to those fallen in war defending the country. Flanking this glorious stone poem to the country’s greatness are two art museums: the Museum of Fine Arts and the Hall of Art. (Unfortunately I didn’t give myself time to visit either.)

Beyond Heroes’ Square is City Park (not very creative names, these), one of the finest parks in Budapest. As you might have guessed, this park was also created for the Millennium Exhibition, and signs of that epochal celebration are not far to seek. The most obvious is Vajdahunyad Castle, a full-scale replica of Corvin Castle, which is now in Romania. This castle was originally built of wood and cardboard and meant to be temporary, but the Budapestians liked it so much that it was rebuilt in stone. Yet aside from these architectural fantasies, the park is also simply a nice place to be. I bought a glass of steaming mulled wine from a street vendor and walked around, enjoying the sight of Hungarians at play.

One thing I did not do, but probably should have, was to visit the Széchenyi Baths. This is a massive thermal bath complex where you can go and soak in water that ranges from warm to scalding. It is one of the most distinctive and famous attractions in the city, but I felt uncomfortable going by myself. To make up for my own cowardice, I recommend you, dear reader, to give it a try.

The other park I visited in Budapest was neither on the Pest nor the Buda side, but right in the middle of the Danube. This is Margaret Island, the green oasis in the center of the city. It is named for a Hungarian Saint, and in the past was covered with churches and monasteries. But the nuns and monks fled during the Turkish invasion. Now there are only a few ruins left to remind visitors of this history. Mostly, it is just a nice place to take a walk. But I was training for a half-marathon, so I decided that I would visit at a faster pace. I soon discovered that Margaret Island is a wonderful place to run. A track—made of special, bouncy material—runs along the edge of the island, allowing you to run with a view of the Danube and the city beyond. Perhaps it was the cool breeze coming off the water, or the thrill of running in a new city, or the competition from the other runners, but I was significantly faster than usual.

So far I have covered a great many monuments on the Pest side. But there remains the other half of the city to explore—the hilly, more sedate Buda.

Perhaps the most famous attraction on the Buda side is Fisherman’s Bastion. It is a place made for Instagram. Constructed around the turn of the 20th century, it is a kind of neo-medieval fantasy castle, whose ornate walls provide an iconic view over Budapest. Its name is due to the fact that the fish market used to be nearby.

Right next door is Mattias Church, perhaps the most beautiful house of worship in the city. Though a church has been here for over 1,000 years, the building as it stands now is gothic in style. It has been through a lot. Among other tribulations, during the Ottoman period, the church was converted into a mosque; then, it was extensively remodeled for the Millennium Exhibition of 1896; and finally it was severely damaged during the Second World War. In any case, the church is absolutely lovely, both inside and out. The imposing gothic exterior—softened by the colorful tilework—yields to a playful explosion of polychrome patterns inside.

Right next door to these two monuments is Buda Castle, an enormous palace that sits on top of castle hill. The original Baroque palace was probably quite remarkable. Unfortunately, however, it was almost completely destroyed during World War II, and the rebuilt castle is not nearly as charming. Or so I hear, since I decided not to visit for myself.

My next stop was Gellért Hill, which is one of the highest points in Budapest. I was unlucky, however, as I discovered that the top was closed off for some sort of construction work. I had to content myself with a visit to the Garden of Philosophers. This is a bizarre park a little ways down the hill, which features an assemblage of statues of major religious leaders: Jesus, Abraham, Buddha, Laozi, and Akhenaten (the Egyptian Pharaoh who created a monotheistic cult). Also present are Gandhi, the Bodhidarma, and Saint Francis of Assissi. (Notably absent is a representative of Islam; but of course depicting Muhammad would be, to put it mildly, controversial.) All of them are gathered around a small metallic ball, which represents their common goal. This was the work of a Hungarian sculptor, Nándor Wagner, who wanted to symbolize the commonalities between different faiths. While the idea that the various religions are striving after the same thing is certainly appealing, I think the sculptures are quite compelling in themselves as human figures.

Another popular attraction on the Buda side is the Hospital in the Rock. This is exactly what it sounds like: a hospital built into the side of a hill, using a previously existing network of tunnels. These tunnels had been used for centuries by locals as food cellars. In the leadup to the Second World War, the tunnels were equipped with medical equipment and staffed with doctors. But the casualties overran the hospital’s capacity by over 600%. The guide (and you have to visit with a guide) explained that doctors had so few materials that they had to reuse bandages, with predictably grizzly results. After the war, the hospital was repurposed as a kind of nuclear shelter, though it was never used in any emergency situation again. (The guide also said that it couldn’t have withstood a nuclear attack, anyway, as it is not deep enough.) Now the tunnels are filled with hundreds of wax dummies and old equipment, providing a graphic (if silly) illustration of the hospital’s history.

All of this was wonderful enough. But my favorite thing on the Buda side—maybe in the entire city—was Memento Park.

Getting there is not easy. Located on the city limits, it is only accessible by bus. I complicated matters by taking the right bus in the wrong direction; but I realized soon enough, got out, crossed the street, and was soon on my way.

Memento Park is the dustbin of history, a place where all of the Soviet statues were put after Hungary became independent. It is located in a suburban neighborhood, but you can’t miss it: there is an enormous brick platform topped with the boots of Joseph Stalin. The complete statue was actually destroyed during the Soviet Union. In 1956, the Hungarians attempted to throw off the Soviets. The Red Army crushed the uprising in a matter of days, but not before the Hungarians had a chance to destroy this hated symbol of Soviet Rule. I went inside the base of this statue, and discovered a room full of busts of Stalin and Lenin.

Next to the entrance is one of the best statues in the park: a cubist rendition of Marx and Engels, made from granite taken from the Mauthausen Concentration Camp. The little kiosk where you buy your tickets is an attraction in itself—full of old Soviet knicknacks. You can, for example, buy a real Soviet passport or postcard, or even a CD with old Soviet anthems. With my ticket, I also purchased a little booklet that explained each of the statues on display. I was glad I had it, since otherwise there was little signage.

Walking around the park is a surreal experience. Dramatic and triumphant statues sit decaying in a field, almost as Washington D.C. would appear after a disease wiped away humanity. The bulk of these statues are in the recognizable Soviet social-realist mode—heroic soldiers, stolid workers, and the occasional full-bodied woman. As works of art, they rarely rise above propaganda, though they are wonderfully evocative of that era. And some are indeed memorable.

One favorite of mine (for obvious reasons) was a monument to the Hungarians who fought in the Spanish Civil War. Three rather frighteningly abstract soldiers stand saluting next to a pile of rocks, on which are inscribed the names of battles during that war. Another highlight is the Martyrs’ Monument, created by Kalló Viktor, which shows a barefoot man reaching out towards the sky as he collapses (presumably from being shot). Just as dramatic is the Republic of Councils monument, which shows a victorious worker rushing forward.

But my absolute favorite is the Béla Kun Monument. Kun’s life illustrates the ups and downs of the communist movement. He fought in the First World War for the Austro-Hungarian empire, was taken prisoner by the Russians, became a communist, returned to Hungary, and led a revolution in his native country. Then, when the Hungarian Soviet Republic collapsed, he escaped to Soviet Russia and participated in political purges. But he reaped what he sowed, as he was himself eventually accused of Trotskyism and executed. It was only after Stalin died that he was rehabilitated and made into an official hero, as depicted in this posthumous monument. This is unlike any statue I have ever seen. Kun stands on a platform, pointing with his hat, while a mass of soldiers march to war beneath him. The chrome plating on the soldiers and their odd, compressed dimensions made them look like toys. It is so silly that it parodies itself.

Everything I had seen and read—not least the Béla Kun Monument—indicated that communism was not a happy time for Hungary (or the Soviet Union, for that matter). Nevertheless, I admit I found it touching that ordinary workers were held in such high esteem. It may have just been propaganda, but even paying lip service to workers is better, in my opinion, than our worship of the super-rich.

All philosophizing aside, the final exhibit made it very clear what the Soviet Union was actually about. Showing in the adjacent exhibition center was a film by Gábor Zsigmond Papp, in which he had edited together films used to train the secret police. Consisting of four parts—hiding bugs, searching houses, recruiting, and networking—the film was a shocking illustration of the strategies that secret police would use to search out political dissidents. I remember scenes of agents sneaking into a gym locker room to plant a listening device, or picking a lock in an apartment when somebody wasn’t home, in order to search it. (The agents were careful to put everything back where it was, so the suspect wouldn’t know they were there. Apparently, some people would leave small objects, like a hair, stuck in a closed door, so that they would know if the house had been entered.) Clearly, privacy was not a priority during this time. If ordinary people were celebrated openly, they were persecuted secretly.

This was my final stop in Budapest. I wandered back into the bright spring day, walked into the suburbs, and caught a bus back to the city center. It had been a wonderful visit. Budapest is convenient, comfortable, cheap, and full of art and history. And it certainly does have a vibe.