My school year thus far has been dominated by the Global Classrooms program. This is an educational initiative that resulted from a collaboration between the Comunidad de Madrid, the British Council, the United States Embassy, and the Fulbright program, in which students in their third year of secondary school (American 9th grade) participate in a model United Nations conference. The program has grown every year since its inception; this year well over 100 high schools took part.

Each year it is one language assistant’s job to implement the program in their school—and this year it was my job. This meant preparing my students for the first conference, which took place the third week of January. This gave me about twelve weeks of class to work with the students.

I was lucky. For one, the program has been running for many years in my school, so the teachers are very supportive. I had also seen the program in action already, during the past two years at my school, so I knew what to expect. What is more, instead of the required two hours per week with students, I had three hours to work with them. But I did have one slight disadvantage: my number of students was higher than average. I had four class groups, each with nearly 30 students, so almost 120 in total.

Despite the extra time, I still felt rushed. The students need to master quite a number of skills before the conference. First I had to explain what Global Classrooms is, which meant explaining what the United Nations is. Then there is public speaking. Most people—let alone teenagers—do not feel comfortable speaking in front of a large group; and when you add a second language into the mix, you can see why this would be quite a challenge. Another difficulty is teamwork, since the students must work in two-person “delegations,” doing their best to share the responsibilities equally.

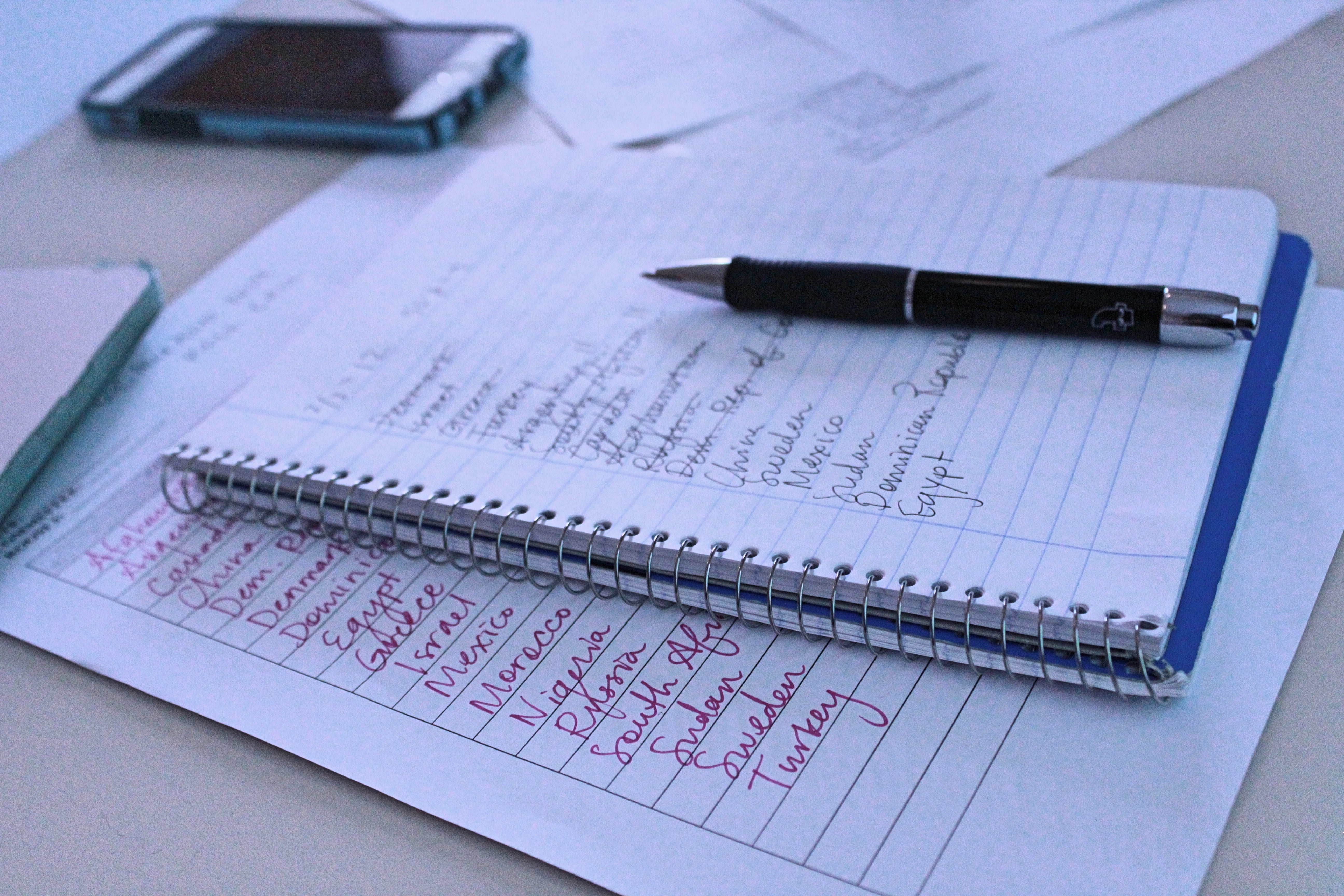

After the class is divided into delegations and assigned countries, they must write papers and speeches from their country’s perspective. This means doing research. For most of these students, this is the first time that they are asked to diligently search for reliable sources and cite these sources in the proper format. Believe me, it can be a struggle trying to get students to not use Wikipedia (especially since I use it so much). Added to this, the temptation to plagiarize is especially strong in a foreign language, since paraphrasing can be quite difficult for a non-native speaker.

The two major pieces of writing the students must produce are the Opening Speech and the Position Paper (a short research paper). The former is essentially a shortened version of the latter, since the students need to be able to read their speech in 90 seconds. In both, they must examine a global problem from a domestic and an international perspective, explain what their country has already done to address the problem, and then propose solutions for the future.

This year the problem assigned to my school was Gender Violence—a very timely issue. Thus, the students had to wrap their mind around the forms and causes of gender violence—both in the world and in their own countries—in order to come up with persuasive solutions.

The last piece of the puzzle is parliamentary procedure. The students need to learn the different sections of a conference (formal debate, moderated caucus, unmoderated caucus), how to make a point or a motion or to yield their time (and all the different ways of doing so), and how to write a proper resolution (a proposal to solve the problem).

Teaching these things may sound dry (and can be); but it was made somewhat more engaging by teaching it through a “Zombie Conference,” in which the students had to find a solution to the impending zombie apocalypse.

The effort to impart all of these skills is rewarded when you see the students in action. By December, my students (well, most of them) were able to operate within a formal environment, speak in public, write a properly-researched paper, debate a global issue, and in general impress all of the adults in the room with their poise and maturity. It is quite a payoff.

Because so many schools are participating in the program, each school may only send 10 students to the first conference in January. I admit I was a little disappointed by this, since it meant choosing between several deserving candidates. But in my school (as in many others) we compensated by having our own conference in December, in which every student could participate. This may have been the most rewarding part of the whole experience for me. It is the middle-range students, the ones who do not normally excel, whom an educator most hopes to reach—since the ones who do normally excel hardly need your help—so it was gratifying to see so many of these students improve.

After this conference in December we picked our team of 10 and began preparing them for the January conference. This meant re-writing position papers and opening speeches, brushing up on parliamentary procedure, and discussing the program of gender violence in greater depth. It can be a nervous time for the students, since they know that only about a third of the schools advance to the next conference (which takes place in late February). Is it important, then, for the students to see the conference, not as a cut-throat competition, but as a learning experience—which it is.

This year so many schools participated that the conference had to be spread out over six days. It is a big operation, and so each of the Global Classrooms language assistants is required to help run the conference. My job was to be a photographer. It was my first stint as an events photographer, though hopefully not my last. At least now I can reap the benefits of my work, since I have a stockpile of photos that I can use to illustrate the event.

The conference took place at CRIF Las Acacias, a labyrinthine old building (now a center of “innovation and training”) which had been a state orphanage for nearly 100 years (1888 – 1987). I had the privilege of being taken on a small tour of the old church. It sits empty nowadays, cavernous and deconsecrated, beside the main building. The old altar still stands, the virgin presiding over empty benches. Nearby is a theater—now shrouded in darkness—that the orphans would use to stage plays. Few places I know have such a delightful feeling of being abandoned and even haunted by past lives.

But on the days of the conference, present lives were what attracted the most attention. Students in suits and ties, dresses and high heels, gave impassioned speeches in excellent English about complex and controversial issues. The day would typically start off somewhat tense, with the students nervously eyeing those from other schools, and doing their best to outshine their opponents. But the atmosphere noticeably mellowed as the conference went on (it runs from 8:00 am to 3:00 pm), until by the end of the day each student has accumulated dozens of new instagram followers. Now, that is what I call success.