The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance by Ron Chernow

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

When I picked up this book, I assumed it was a biography of the two famous John Pierpont Morgans. But this is far more; indeed it is a true history of the Morgan bank, though admittedly with heavy emphasis on the biographies of the key figures. Given that this history spans over a century and includes a huge number of players, politics, and policies, the fact that Chernow could put out such a polished book in two and a half years is a testament to his skill as a writer and researcher.

The book is most colorful in its beginning and slowly fades into the dullness of contemporary reality. The Bank of Morgan began with the 19th century financier George Peabody, a sort of Dickensian miser turned philanthropist. Lacking a son, Peabody passed on his business to Junius Spencer Morgan, another personality of a bygone age, who managed to combined pious moralizing with strict business. His son, Pierpont, is by far the most colorful character in this panorama. A rabid art collector, an amateur archeologist, and an inveterate womanizer with a swollen nose and an enormous yacht, Pierpont was a central figure in the American economy of his age.

His son, “Jack,” though resembling Pierpont physically, was a far more mild-mannered sort of banker. His life is mostly lacking in racy and romantic stories (except for the time he was shot by a would-be assassin). The Morgan line mostly fizzles off after Jack; but there are many other Morgan bankers to take note of. The most important was undoubtedly Thomas Lamont. Chernow tracks Lamont’s strange journey from the cosmopolitan advocate of the League of Nations to an apologist for Italian fascism and Japanese aggression. It appears wide culture and smooth manners do not immunize one from ugly politics.

The wider historical arc of Chernow’s book gave me a bit of nostalgia. We begin with bankers in top hats and stiff collars, guzzling port wine and sucking on cigars. (Pierpont was a heavy drinker and smoker, and believed that exercise was unhealthy.) These bankers relied on charisma and relationships as much as they did on any technical understanding. The early House of Morgan was paternalistic towards its employees and stressed an esprit de corps—the importance of banking tradition over personal egos. This sleepy world of respectable bankers gives way, in the late twentieth century, to the high-octane world of trading, where highly trained employees work twelve-hour days trying to beat one another in an enormous casino.

The activities of the bankers also change markedly in this history. While nobody would argue that Pierpont was saintly or altruistic, his main activities consisted of reorganizing industrial companies to make them more productive and effective. This is a great contrast with the bankers of the 1980s, who are mainly concentrated on speculative activities and hostile takeovers which seem to have very little to do with work of real value.

Of course, my impressions of this history are colored by the fact that I know relatively little about finance and thus at times had trouble following the business side of things. Chernow, for his part, is typically vague when it comes to any technical details; his preferred style is to focus on individuals and their foibles. This was a bit frustrating, since I felt that I could have learned more had Chernow simply included more in the way of explanation.

But, as it stands, this is an extremely readable and compelling history of one of America’s most important banks. Things have changed since the publication of this book. Morgan Stanley is still going strong, though J.P. Morgan mainly serves as a brand used by Chase bank, and Morgan, Grenfell & Co. does not even exist as a name anymore. Even 23 Wall Street, the iconic home to this iconic bank, now sits empty and unused, apparently owned by a shadowy billionaire who is reportedly sitting in a Chinese jail. Such is the fate of all great empires.

View all my reviews

Month: August 2020

Review: A Brief History of Neoliberaism

A Brief History of Neoliberalism by David Harvey

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

It is one thing to maintain, for example, that my health-care status is my personal choice and responsibility, but quite another when the only way I can satisfy my needs in the market is through paying exorbitant premiums to inefficient, gargantuan, highly bureaucratized but also highly profitable insurance companies.

Neoliberalism is a term that is often thrown about; and yet, like socialism and capitalism, I often feel that I do not quite know what it means. Its common definition—the preference for free trade and free markets—did not seem to distinguish it from capitalism itself, as I understood the term, which made me wonder why neoliberalism was so controversial and hated.

Harvey’s book goes a long way in answering this question. The best way to understand neoliberalism may be historical. After the end of the Second World War, governments were dominated by Keynesian policies—that is, the use of taxation and spending (if necessary, deficit-spending) to control boom and bust cycles. But in the 1970s the Keynesian consensus broke down as a result of stagflation: low growth combined with high inflation. The failure of Keynesian policies to get the economy out of its rut led, eventually, to the embrace of quite a different governing philosophy: neoliberalism.

This has many intellectual components. Neoliberals are—at least in theory—opposed to fiscal policies as a way of fighting economic ups and downs. (In practice, this means that governments must adopt austerity measures in order to keep their budgets balanced in an economic downturn.) In fact, neoliberals are quite generally anti-government, at least in their rhetoric. They favor privatization, deregulation, low taxes, and low tariffs. The central idea is simple and, on its face, compelling. Prices communicate market information far better than a government can manage; individuals understand their own needs better than the government; and the profit motive is the great driver of general prosperity.

Yet what (ostensibly) began as a great liberation of sovereign individuals and all of their creative genius became, instead, an economic transfer from the poor to the rich. The evidence, by now, is clear that neoliberalization did not jump-start the economy. Growth has never recovered its pre-1970s levels; and economists now admit that they simply do not know how to make an economy grow. But as growth slowed, and wages stagnated for most mere mortals, the rich, richer, and richest made off with ever-increasing slices of the economic pie. Inequality reached such stark levels not seen since the 1920s. Harvey contends that this was not a mere byproduct of the economic philosophy, but one of its primary goals.

If the rhetoric of neoliberalism were, indeed, true—if the government was merely “getting out of the way,” and letting the market do its magic—then claims of nefarious intent would perhaps be unfounded. But as Harvey points out, the neoliberal state is no mere bystander. On the contrary, state power is quite necessary to the operation of neoliberal policies.

Most obviously, if property rights and contracts are sacrosanct, then there must be enforcement—violent if necessary—of those rights. In practice, this also means that there is a double standard between debtors and lenders. In a neoliberal state, the debtor has all the responsibility not to take out a loan that they cannot pay back; and there is very little protection if they do take such a loan. Meanwhile, there is no similar responsibility on behalf of the lender not to lend irresponsibly (as the 2008 financial crash proved); and if the lender does so, the state sanctions any draconian measures necessary to extract repayment.

The state also actively subsidizes the wealthy, both directly and indirectly. It directly subsidizes companies through (among other things) bailouts. The mortgage tax deduction is essentially a handout to the rich—as well as a spur to high-end housing construction. It puts up legal impediments to labor organizations and strikes.

And the indirect subsidies are many. If a community is devasted by a free trade deal, the state deals with the social fallout (often through mass incarceration, in the US). If the housing market leaves many homeless, then the state steps in to enforce eviction notices and provide homeless shelters. If medical insurance is out of reach to many, then the state provides public healthcare and emergency rooms. And this is only to speak domestically. Harvey documents many cases when the IMF and World Bank pressured developing countries to adopt neoliberal policies, and then demanded repayment of loans even if it meant impoverishing their populations.

In sum, the neoliberal state is not a mere onlooker, enforcing class-neutral rights and ensuring a fair game is played without cheating. On the contrary, the neoliberal state serves to provide welfare to the rich while enforcing brutal ‘capitalism’ on the poor.

Yet Harvey is not only valuable in his catalogue of neoliberal hypocrisies. Many of the most interesting parts of this book, I found, were Harvey’s reflections on how neoliberalism has transformed the culture. His contention is that the 1960s era emphasis on personal liberty has led to a kind of atomization of society. As more and more people are convinced that the government is evil or at least useless, people seek different forms of community. This can take many forms: religiousness, political populism (which Harvey predicts), or, for the progressively minded, NGOs. Indeed, one can see the rise in NGO activity as a kind of tacit defeat by the left, as they have yielded the possibility of democratic, governmental action, and instead turned to privately owned organizations run by elites.

More broadly, the embrace of a radically individualist philosophy makes political organization difficult. How can you politically unite people behind the idea that the government is the problem? Few forces have been able to transcend this limitation, most notably nationalism—giving birth to neoliberalism’s ugly cousin, neoconservatism. Other collective bonds—such as race, gender, or sexuality—do not have the widespread pull of nationalism, which Harvey believes gives the left a chronic disadvantage.

Harvey’s solution to this (unsurprisingly, given that he is a Marxist) is to make class, once again, a basis of political mobilization. It is only when workers collectively reform the society that the rich can be defeated. Unfortunately, the two economic crises that have transpired since this book was published have yet to make that happen. Nevertheless, I think this is a valuable and incisive book about one of our era’s most distinctive features.

View all my reviews

Marseille: Southern France

Marseille’s reputation—at least as a tourist destination—is not enviable. Virtually everyone I told about my upcoming visit raised their eyebrows. They told me that the city was very dangerous and should be avoided. One person told me that a friend of his, while merely driving through Marseille, had a gun stuck in his face through the car window. For my part, I would have never even considered going if one of my oldest friends had not, by chance, been living in the city for his historical research. He was very enthusiastic about the place, and assured me that I almost certainly would not get shot.

(According to this website, however, Marseille does indeed have the highest crime rate of any major European city—or at least in 2018. You are warned.)

Marseille is the second-largest city in France—though its population of around 850,000 is fairly modest—and the third-largest metropolitan area, after Lyon. (Need I mention which city is the first?) Like many European port cities, Marseille has a long history, dating back at least to the Ancient Greeks. Indeed, during the construction of a shopping center in the Place Jules Verne, the remains of two Greek ships were found. (If you would like to learn more, here is an hour-long documentary about the attempt to reconstruct one of the boats and sail it in the port.) Not ones to miss a strategic position, the Romans also set up camp here,

By the time I arrived, I had an entire posse awaiting me. Greg—the aforementioned historian—was accompanied by my brother (who had arrived the day before), and Lily, another old friend from New York, who was coincidentally visiting at just the same moment I was. Four denizens of the Hudson Valley thus found themselves thrown together in Mediterranean France, looking for a good time.

After dropping off my bag, the first item was lunch. Marseille is fortunate in having a robust culture of street food—particularly pizza. Just down the block, we found a food truck selling pizza baked in a wood-fired oven. And it was good: with a savory tomato sauce and a few anchovies. I mention this because, for all of its many delights, Madrid does not have a street food culture to speak of (Spaniards always eat sitting down) and also lacks a good pizza culture (Dominos is popular). So I was already rather taken with the city.

The repast done, we then boarded a city bus that carried us beyond the city limits. We were going to visit one of the treasures of the area: Calanques National Park. At first I did not know what the fuss was about. The bus left us near a trail, leading us into an entirely typical Mediterranean landscape: with dry, sandy soil, diminutive pine trees, and sun-baked rocks. Indeed, the area was strangely reminiscent of hiking trails in the Guadarrama mountains of Madrid. We carried on walking, pausing occasionally on the wooden benches, smelling some of the wild rosemary growing along the path, until we reached the coast.

Here is where the park became spectacular. The landscape swelled into peaks and then dropped in sharp cliffs towards the sea. The rough and rugged limestone shone pale in the sunlight, like old bone. This arid landscape contrasted sharply with the aquamarine glow of the Meditteranean. The result was quite dramatic. My favorite touch were the little white sailboats in the distance. We climbed a peak and took in the expansive sight, marvelling at how little the boats appeared amid the seething rock. It is difficult to contemplate such a scene—reflecting on the millenia it must have taken to form—and not feel both physically tiny and temporally insignificant.

After taking in the natural spectacle, we walked back to the bus and headed toward the city center. I want to mention something that we passed along the way, but which we unfortunately did not take the time to stop and see: the Unité d’Habitation, a modernist apartment building designed by Le Corbusier, the great French prophet of modernist architecture. Indeed, the building in Marseille is considered to be a prototype of his Utopian vision of urban planning—spaces designed to equalize social rank, to create a more open and organized city, and to embrace the efficiencies of the industrial age. Unfortunately, Le Corbusier’s vision did not pan out so well in practice, as high-rise apartment buildings were used all over the world as public housing for the urban poor, thus isolating them in corners of the city with few other resources.

Looking at the building in Marseille, however, one does feel a sense of utopian inspiration. Visually it is quite striking: with the entire concrete edifice elevated on stilts, allowing pedestrians to walk under and through the building. Thus, the apartment is integrated with the green spaces on either side, fulfilling the old notion of the ‘garden city.’ The wall panels around the windows are painted red, yellow, and blue, creating an attractively retro color scheme. At least part of the building is now a luxury hotel; and judging from the photos online, the retro aesthetic is maintained throughout. Another part of the building is a modern art museum, in which the visitor can ascend to the roof to enjoy some odd concrete excrescences, as well as a beautiful view of the city and the sea. There is even a nursery school in the building. Despite the attractive and thoughtful design, however, I would much prefer a room in a smaller building, better integrated to the life of the city. Good neighborhoods are organic rather than planned.

It was already getting a bit late, so our next step was to have a night on the town. But first we had to have a little snack. For this, we went to a local shop to buy a baguette and some cheese. Now, I cannot say that I am a particular fan of cheese, or even bread; but this little meal was quite impressive. First, the baguette was far better than what I was used to from New York or Spain—nicely crusty on the outside, while not too flaky, and almost creamy on the inside. The cheese was even more delicious. We bought three kinds (don’t ask for their names), all of them tasty. One in particular impressed me: it had three separate flavors—a sharp attack, a buttery middle, and a bitter aftertaste. The French deserve their reputation.

Evening was fast approaching, so it was time to head into the center of town. In Marseille, this almost inevitably means walking towards the water. We followed the gently sloping ground down to the city’s cathedral, which sits within a few hundred feet of the sea. It looked quite lovely in the waning daylight. Of relatively recent construction (for Europe), the cathedral was made in a Byzantine-revival style, with ample domes and circular arches—a far cry from the angular French gothic. The alternating horizontal bands of dark and light stone used in the facade give the building a playful charm. (Though I did not see it during my trip, I later learned that the much older, much smaller original cathedral can still be seen beside the modern building.)

As the sun sank below the horizon, we found ourselves in the port. Though we were just walking and chatting, this part of the night sticks out in my memory for the vibrant colors that suddenly appeared in the darkening sky. A ferris wheel was lit up neon green, while a nearby museum projected wavy blue lights onto the walkway. The horizon, meanwhile, cooled into an ember glow, turning walkers into dark silhouettes.

But we did not have all night to dawdle on romantic seascapes. We had dinner to eat. For this, Greg took us to a seafood restaurant at the Old Port, where he ordered a terrific platter of the fruits of the sea. There were oysters, clams, mussels, prawns, and crabs, all served on a bed of ice with a few slices of lemon. Now, I admit that I am not the more passionate admirer of seafood; and having it served so raw and unadorned was not exactly to my liking. But there is certainly a kind of purity to such a meal—the unadorned flavor of the Mediterranean.

Our day ended in a bar, over a bottle or two of red wine. From the start, Marseille had maintained a pleasant atmosphere. Contrary to the evil reputation of the French, the people of Marseille were consistently pleasant and friendly. (Maybe it is just the Parisians that are rude.) The city, though not spectacularly beautiful, is full of the charm of old Europe. What is more, since the city does not receive a great deal of tourism, there is a kind of intimacy to the place—the aura of a city that is lived in rather than traveled through. That night, I went to sleep eager to see more.

The next day began with a pilgrimage. We were going to visit Notre-Dame de la Garde, by far the most famous church in Marseille.

There seems to be a universal human urge to climb to tall places and, when possible, build something there. We are willing to endure quite a lot of physical hardship for something as intangible as a view. Of course, there are advantages to having the high ground—most notably, surveillance and defense. This is why so many hills in Europe are occupied by fortresses. Driving through Spain, one even sees castles built on hills overlooking tiny pueblos. Marseille is no different in this respect; a fortress was built on the city’s highest point during the Renaissance.

Before this, the hill had mainly served a religious function, being the home to a gothic chapel. It seems that expansive views, aside from their tactical advantage, also put people into a spiritual frame of mind. When the fortress became militarily useless in the 19th century, the hill reverted back to its primary function as a place of worship. Just as the Marseille Cathedral was getting underway, it was decided to build another large, neo-Byzantine church atop the old fortress. Ever since, the church has served as the most identifiable symbol of Marseille, and the city’s most popular attraction. Hills, you see, are very profitable indeed.

The walk up to the hill was relatively painless (even if we did it before having any coffee). The church presented a splendid sight to us pilgrims, as the sun shone directly behind the building. The basilica is dominated by a large tower, topped with a gilded statue of the virgin. Both inside and out, it is characterized by the same bands of light and dark that distinguish Marseille’s cathedral. In the interior you can find attractive mosaics in a pseudo-Byzantine style. But what I found more charming was the surprising sense of cramped intimacy in the church—pilgrims packed into pews, the walls full of little paintings, and toy boats hanging from the ceiling.

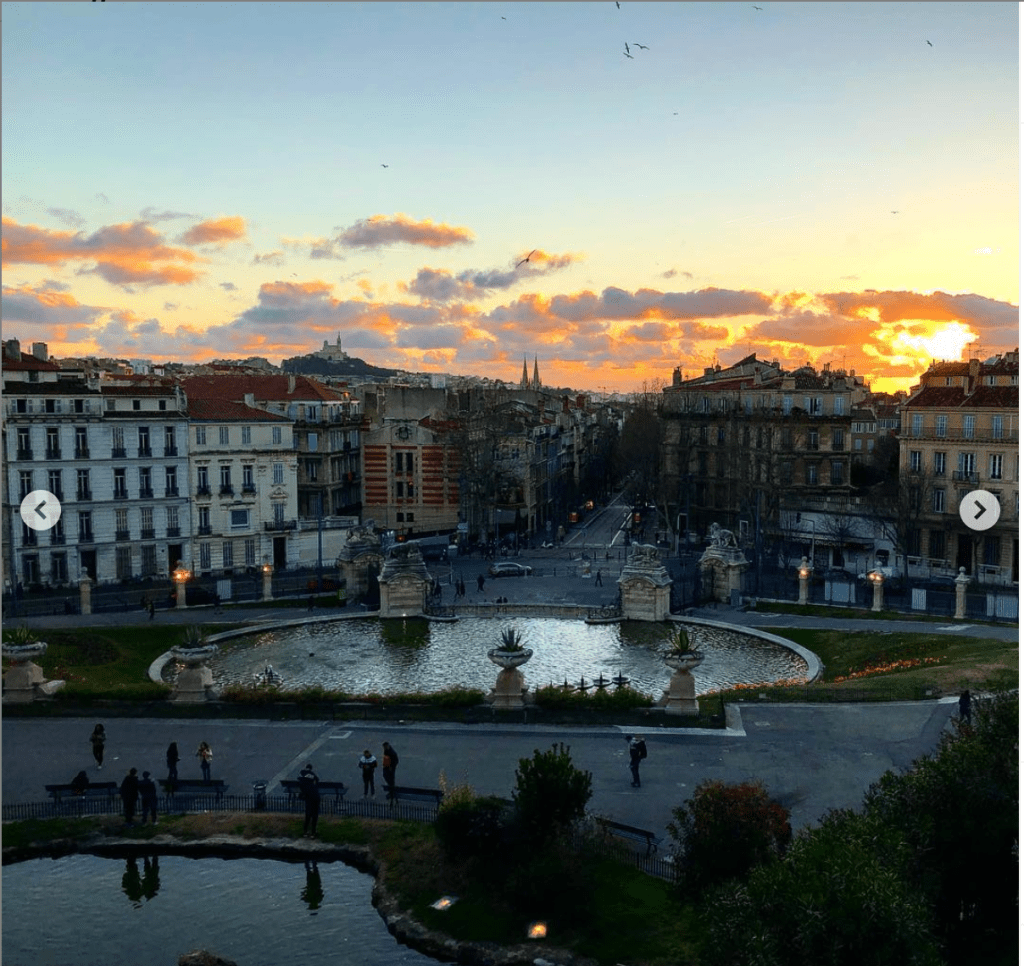

It would be generous, however, to consider the basilica itself an architectural wonder. It is impressive more for its situation than its design. The view is panoramic and thoroughly captivating. You can see the green, grey hills that encircle the city, and the red tile rooftops of the buildings as they fall towards the sea. White sail boats filled the water, accompanied by the odd motored craft.

Off the coast you can see the Frioul Islands (called simply “Les Îles”), four small floating bits of limestone that serve as home to about 150 residents. On the smallest, there is a well-preserved castle (islands are also useful for defense), the Château d’If—iconic as the site where Edmond Dantés was imprisoned in Dumas’s The Man in the Iron Mask. The island was actually used as a prison, in fact; much like Alcatraz, its location made it extremely difficult to escape from.

On the opposite side of the basilica, you can see the white folded shape of the city’s football stadium, the Vélodrome; and beyond that, you can see the monumental conglomeration of apartment buildings, La Rouvière, which seem to be as much part of the landscape as the mountains.

After partaking of the spectacle—and a quick coffee in the café next door—we went back down the hill and returned to the port. There, we visited the Mucem, short for the Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée, which was opened in 2013 when Marseille was dubbed a European Capital of Culture for that year. We did not visit the exhibitions, however, as we were short on time, and Greg assured us that they were not spectacular in any case. Instead, we headed up to the roof, to enjoy another coffee in the modernistic museum building. The outside of the entire structure is covered in a kind of grey, plastic web, like artificial seaweed, which certainly stands out among the sandy-colored stone that makes up the surrounding area.

The visitor can walk directly from the roof of the museum to the neighboring castle, Fort Saint-Jean, via an elevated walkway. This is yet another fortress in the arsenal of Marseille, built during the reign of the Sun King, Louis XIV. The old turrets provide an attractive view of the Old Port, and many parts of the fortification are now occupied by lovely planned gardens. Across another elevated walkway there is the church of Saint-Laurence de Marseille, a lovely old Romanesque church. From there, the old port (le vieux port) is just a short walk away.

(By the way, I have an idea for Marseille’s new official tourism slogan: “Come for the Port View, stay for Le Vieux Port.”)

On any given day, the water is full of hundreds of little white boats, bobbing gently in the tide. Restaurants wrap around the water, offering French classics like moules-frites (though that’s actually from Belgium!). At the end of the port, you will find something which, as an American, cannot but make you pine for the Old World: fishermen and women selling their fresh catches. Little brown and grey fish float in plastic bins, while their vendors call out their prices. And it is no mere spectacle; when I was there, the fisherpeople were doing good business. I am sure it tastes better than frozen fish at the supermarket.

Right next to this little market is a bit of public art, the Ombrière. Like the museum, this is yet another relic of the 2013 European Cultural Capital Celebration—a design by big-time architect Norman Foster. The Ombrière is an elevated roof whose underside is an enormous mirror. This makes for good fun as you walk underneath and crane your neck, and it is a gift to amateur photographers. It would be much appreciated in a rainstorm, too.

Now it was time for lunch. For this, we decided to experience a different kind of cuisine. Because of the city’s location on the Mediterranean, and owing to France’s colonial past, Marseille has a deep connection with Northern Africa (the Maghreb). Thus, there are many thousands of immigrants in the city; and of course they brought their food with them, too. This was readily apparent when we sat down to have some kebab. Of course, kebab is a European staple, to be found anywhere. But this kebab was special—not the cheap ground meat sandwich with ketchup and mustard, like you find in Spain, but a properly spiced dish with good ingredients. I was very happy with my meal.

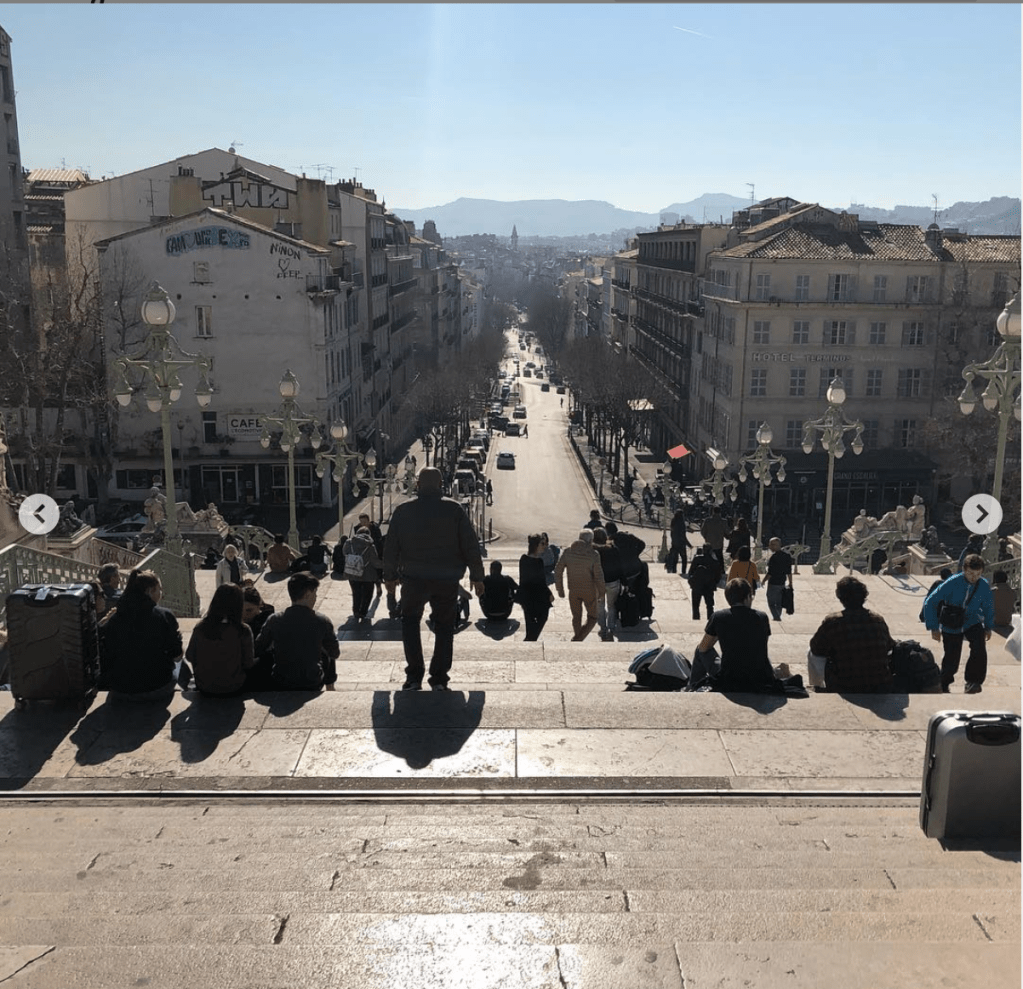

After lunch, my brother had to catch his flight back to Madrid. (Our visits were staggered since we had different days of the week off.) This meant a little trip to the city’s Saint-Charles train station so he could catch the bus. Though you may not believe it, this train station is one of the architectural highlights of Marseille, mostly owing to the richly decorated grand staircase—adorned with statues, columns, and elaborate light fixtures—that leads from the city center up to the station building. The station building itself is quite attractive as well, a classic open metal frame.

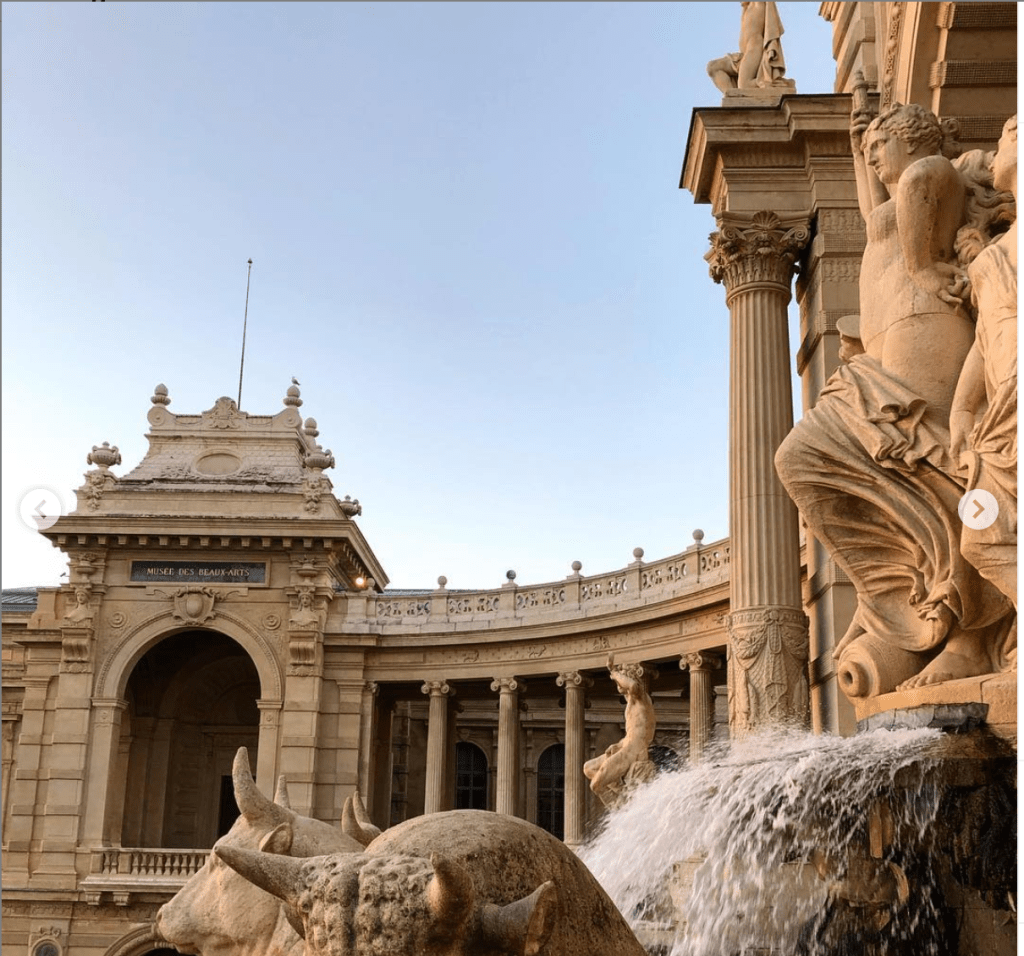

But we did not have all day to contemplate train stations. There was still one monument left on the agenda: the Palais Longchamp. This is indeed a palatial building, though not really a palace: it is a piece of celebratory architecture, a monument to the completion of the Canal de Marseille.

This canal, completed in 1849, was an enormous engineering triumph, requiring the building of tunnels, bridges, and aqueducts in order to transport the water 50 miles (80 km) to the city, using just the pull of gravity. To this day, the Roquefavour Aqueduct—built to carry the water over the Arc valley—is the largest stone aqueduct in the world, stretching 375 meters (1,230 feet)! The canal still provides the majority of Marseille’s water. (New York City’s Croton Aqueduct, another monumental project, was completed at around the same time, and traveled a similar distance. Both projects were motivated by similar problems—growing population, salty local water, and outbreaks of cholera—but the Croton Aqueduct was supplanted within just a few decades.)

Given this background, you can understand why the Palais Longchamp is truly a celebration of water. The two wings of the building extend out from the central arch, where a statue of some Greek goddess rides atop the waves. Water pours down a mossy basin into a pool, and continues falling down towards the street. The visitor can enjoy this splashy spectacle from the two monumental staircases that wind up on either side, which lead through the triumphal arches to the lovely garden on the other side. The two wings of the structure, I should note, are home to two museums: the Museum of Fine Arts (on the left) and Natural History (on the right). They were both closed by the time we got there, though. So we contented ourselves with sitting aside the fountain, having a good chat, and drinking from a bottle of red wine my friend brought along. As far as French evenings go, this was one of the best.

We finished up the night with a home-cooked meal. For this, we took advantage of the North African influence in French cuisine—a lasting relic of the French colonies. We bought merguez sausages, couscous, and eggplant, zucchini, and tomato for a ratatouille. This meal, so simple, made a lasting impression on me, and I have tried to replicate it many times since. The merguez was particularly impressive: made from lean lamb meat, full of garlic and spice, it is very much unlike the sorts of sausages available in Spain. The couscous—also not popular in Spain—was light, fluffy, and filling, while the ratatouille (made by my talented friend Lily) was wonderfully flavorful.

The night ended, as it always must, with an episode of a history documentary—this one, about the Spanish Civil War (free on YouTube). It had been a wholly enjoyable day.

I did not have much time before my flight the next day. And I had even less time to see Greg, since he had to go work (he was researching in a government archive in the area). So after a breakfast with Lily, I headed off to see one final Marseille monument: the Abbey of St. Victor.

This is an extremely old monastery—dating from the fifth century—though it was mostly destroyed by invading Vikings and Saracens, and later rebuilt in the tenth century. The abbey is situated next to yet another old castle, the Fort-Saint-Nicolas; and indeed the church looks quite formidable itself: its high, crenellated walls make the building look more military than devotional. Certainly, positioned as it is with a commanding view of the old port, the church would have been a good defensive structure in the case of an invasion. Though I am not sure that the monks would have made the best warriors.

The building is just as formidable on the inside as without. Spare of decoration, the visitor is confronted with grey stone walls forming a somber environment. Even more dark and gloomy is the crypt, where the visitor can find half-ruined tombs and cracked carvings. Yet the building’s interest goes even further back than the church’s founding, as a Greek-era quarry was discovered here, as well as a Hellenistic Necropolis. As so often happens in Europe, history is simply piled on top of itself here.

Before my bus left to the airport, I had just enough time to eat some more delicious kebab. That may have been a mistake, however. All of us experienced some sort of stomach problem either during or after our trip. Lily got sick on the way over from New York. In my case, for many days after returning to Madrid, I would find myself nauseated after eating just a bit of food. It was rather odd.

Infirmity or no, however, I thoroughly enjoyed my time in this supposedly dangerous city. One comes away from Marseille with a very different image of France than the typical Parisian experience. The people were friendly, the food relatively cheap, and the environment thoroughly Mediterranean. I would gladly return to see more of the region.

Review: Good Economics for Hard Times

Good Economics for Hard Times: Better Answers to Our Biggest Problems by Abhijit V. Banerjee

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Economics is too important to be left to economists.

After listening to a series of lectures on introductory economics, I was struck by the degree to which the basic logic of supply and demand was used to make sweeping pronouncements about human behavior and economic policy. The lecturer, starting from the premise that supply and demand is inexorable, would rule out certain policies as working against the market, while promoting those he considered ‘market-friendly.’ But rarely did he stop to actually examine a case study to see how these theories played out, leaving me with the impression of a wholly a priori logic.

The central thrust of this book is that a priori logic cannot be trusted. The economy is complex and unpredictable, so the best way to understand it is through historical case studies and randomized control trials. The authors find that, when we examine the economy in such a way, many of our intuitions about how the it works or will respond to certain policies are wrong. Indeed, though this could hardly be called a revolutionary book—its tone is engaging but mostly academic—the two authors, Banerjee and Duflo, reach quite heterodox conclusions.

One basic economic argument used against permissive immigration policies is that the increased supply of cheap labor will inevitably drive down wages, thus hurting native workers. The logic is simple but it does not hold up under the evidence. In case study after case study, immigration is shown to be either economically neutral or beneficial to native workers. Indeed, ironically—and contrary to what Trump and his ilk may say—low-skill immigrants are better for native workers than highly skilled ones, because they often take jobs that native workers do not want—jobs requiring little communication and much labor. Native workers may even benefit by being promoted to managerial roles. A multilingual immigrant doctor actually competes more directly with native workers than a monolingual immigrant fruit picker.

Perhaps you can see that the above supply and demand argument against immigration is simplistic, since immigrants, apart from increasing the labor supply, also increase demand for goods. Indeed, most professional economists are decidedly in favor of migration. Workers have much to gain from moving to where their skills will be most highly rewarded; and businesses would gain from having good workers. But here the economists’ logic is shown to have its own flaw. Real workers are actually quite averse to migration. Banerjee and Duflo show that, even when a better job may just require move from the country to the city, most will simply not go. There is a large amount of inertia built into real people’s lives—the pull of family, friends, and familiarity—which works against even obviously beneficial moves.

This is not the only way that the real economy is (in economic parlance) ‘sticky.’ Though economists imagine a world of workers ready to move and re-train, of companies willing to fire and hire, banks that drop bad investments and jump on promising new ones, firms willing to relocate to new countries with cheaper labor, new businesses popping up and inefficient ones disappearing—in a word, a dynamic world governed by shifting supply and demand—the real world is consistently stickier than this logic suggests. This seems particularly true in the developing world—the authors’ main area of study—where they found that efficient and inefficient businesses coexisted, where bad-selling product lines were retained, where banks merely rubber stamped loan applications from existing clients, and where people do not migrate for work, or even take the work that is available locally.

Inhabitants of planet earth will likely not be surprised by all this. But the upshot, the authors argue, is that free trade does not deliver all that it promises. Now, the logic of free trade is simple and compelling, grounded in the law of Comparative Advantage put forward by David Ricardo. Simply put, this law states that we all will benefit from trade, since we can all specialize in what we are comparatively better at doing.

But the logic has not exactly played out as hoped. Though touted as a way of propelling developing nations out of poverty, in practice free trade policies have a mixed record. The authors use the example of India, which transitioned from a highly-regulated economy with high tariffs to a free market with low tariffs in the 1990s. The result of this transition was hardly the economic wonder that some economists could have predicted. In many places, wages actually went down rather than up, and in subsequent years much of the economic growth has simply gone to the country’s rich. This is not to say that the results of economic liberalization were all bad, only that it was hardly the panacea that free-market advocates promised.

The consequences for rich nations, like the United States, have also been mixed. While most economic transitions involve winners and losers, the shock of free trade has benefited those who were already ‘winning,’ and hurt those who were already ‘losing.’ In other words, while the big cities full of college-educated workers have grown richer, the arrival of cheap goods—mostly from China—has ravaged many blue-collar communities.

Admittedly, the theory of Comparative Advantage does predict that free trade will temporarily hurt some workers who are forced to compete with cheaper goods from abroad. But the belief in economic adaptability (not to mention the political will to help assuage the problem) was overly optimistic.

Even when jobs disappear, workers do not move. Many simply go on disability and leave the workforce entirely. In short, workers are sticky. Not only that, but the United States has been very bad at redistributing the gains of free trade in the form of worker retraining and extended unemployment. No wonder that many in the country are skeptical of the benefits. However, the authors are careful to note that the solution to this problem is not to impose new tariffs on China. This will only create further economic harm in other sectors (like agriculture) without remedying the harm already done. What is needed, the authors argue, are generous government programs to either re-train displaced workers, or to subsidize industries that are being driven out of business.

This leads us to the longest and most theoretical chapter in this book, that on growth. The argument is fairly dry but the conclusion the authors reach is striking: we do not know what makes economies grow. The greatest years of economic growth were between the end of WWII and the 1970s. This was also a time dominated by Keynesian economics, which led many to give Keynes the credit for this economic miracle. But the magic wore off with the coming of stagflation, which the Keynesian seemed powerless to stave off. This crisis brought the managed economy into discredit, and ushered in the neoliberal revolution, where deregulation, lower taxation, and free trade were seen as the best tools to rejuvenate the economy. Unfortunately, that did not work, either, and growth has never picked up to pre 1970s levels.

Instead, what has grown since the neoliberal turn has been inequality. Rather than stimulate the economy into mad activity, these policies have merely directed what modest economic growth there has been to the much-maligned top 1%. And their political influence has grown right along with their fortunes, which only reinforces the government’s tendency to embrace these sorts of ‘business-friendly’ policies.

As usual, the economic logic used to argue in favor of these policies—that lower taxes on the rich will spur greater activity—is supported by a priori logic rather than actual evidence. But the evidence does not bear it out. People work just as hard whether they are being taxed at 30% or 70%, or not at all, as demonstrated by a series of tax holidays in Switzerland. The notion that high salaries reflect employee value (which supply and demand would predict) is also not supported, as demonstrated by the remarkably high wages paid to those who manage stock portfolios, which consistently underperform against index funds—meaning that the wages are essentially a rent for holding onto money. (And since the high salaries in finance influence salary negotiations in other industries, this increases salaries across the board.)

A strange picture emerges from all this, a picture of an economic policy—at least in the United States—that is entirely divorced from reality. We wring our hands about immigration at a time when immigration is not going up, and even though immigrants pose no credible economic or cultural threat. We argue about tariffs but not about how to actually help those hurt by free trade policies. We cut taxes and deregulate businesses in the name of growth that never appears. Meanwhile, automation is likely to make many of these problems that much worse, and we persist in putting off any action related to the looming climate crisis.

The current pandemic—and concomitant economic crisis—has only put this magical thinking into high relief. Perhaps the best thing to call it is free-market fundamentalism: the belief that the economy, acting on its own, will sort out all of our problems—from poverty to pandemic—without any government aid. Strangely, it is a faith held most ardently by those who see the least evidence for it: people who have been hit by the economic dislocation of free trade. Indeed, at just the time when inequality is rising, we have embraced a kind of social Darwinism that treats the economic pecking order as a perfect reflection of personal merit. This mentality, resting upon the assumption of an imagined economic mobility (which is even lower in the US than in the European Union), justifies both extreme poverty and extreme wealth, since both are ‘deserved.’ To the extent that anyone is held responsible for the situations, it is either outsiders like immigrants or minorities, or the government—not the wealthy.

As Manny has suggested, the situation is rather reminiscent of the USSR in its final years. In both cases we have an economic philosophy based on a priori logic rather than evidence, and believed on the same grounds. As this philosophy fails to deliver, the country’s elites still do not publicly renounce it, but instead only increase their displays of fervor. Rather, entirely irrelevant factors—immigrants, minorities, nefarious citizens—are used to explain the lack of prosperity. Meanwhile, the rich line their already deep pockets while spouting the old egalitarian slogans. The result is a society gripped by nihilism, wherein the old ideals become barely-disguised lies by corrupt and incompetent leaders, and anger and hopelessness descend upon a country that senses it is going in the wrong direction but does not understand why.

This may seem rather hyperbolic. But when you consider how bad things have gotten in the United States in the short time since the publication of this book, when it was already quite bad, then perhaps you can see the justification.

If our economic logic is often misguided, and our policies either useless or worse, what do the authors suggest? Here is where I thought that the book was mostly lacking. Banerjee and Duflo are extremely heterodox when criticizing conventional economics, but are not nearly so bold in proposing solutions. Their general point, however, is that we ought to shift our focus away from trying to grow the economy—since we do not know how to do that anyway—and towards most justly distributing the resources we have now. High tax rates on the rich will help curb inequality without reducing effective incentives. Coordinated efforts between countries can help to reduce tax dodging, and enforcing anti-trust legislation will help curb corporate power.

The authors have a fairly nuanced view of basic income. They think that basic income schemes work well in developing countries, where the poorest are mostly working a variety of temporary or seasonal jobs. But they do not think UBI would work in developed countries, because people have come to rely on jobs not only for income but for structure and even meaning in their lives. In studies, people who stop working do not tend to increase time socializing, or volunteering, or on hobbies; instead, most people end up just watching a lot of television—which does not increase happiness or well-being. This is why the authors prefer significantly stronger unemployment support—helping workers to retrain and relocate.

This seemed somewhat timid to me. But perhaps it is misguided to seek bold, sweeping solutions from authors who insist on hewing to trial, experiment, and evidence. Hard-headed economists, the authors do not promise miracles. Yet if you are looking for a probing and insightful look at many of our current economic woes—now only exacerbated by the coronavirus recession—then this book is quite an excellent place to start. The most pressing point is that our economical problems have political solutions. As usual, the only thing we need is the political will to start acting.

View all my reviews