The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer by Siddhartha Mukherjee

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I do not consider myself a superstitious person—not even remotely—but somehow I felt a deep reluctance to pick up this book. It may have taken us a long time to figure out the germ theory of diseases, yet the psychology of contagion runs deep. I had the irrational fear that even learning about cancer would somehow unleash it into my life.

But turning away from frightful things is not a good way to live. And, anyway, even though there is a lot of sadness in this book, and a lot to stoke your fears (perhaps it is best to avoid if you have a tendency toward hypochondria), but this is basically a story of innovation.

Mukherjee moves through surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, cancer prevention, and modern targeted drugs, showing how each arose and developed in response to different sorts of cancer and out of the science and technology of the moment. It is a vast story, which includes the development of anasthesia and antibiotics, the discovery of genes and chromosomes, the first research into radioactivity, and the campaign against smoking. To use the obvious metaphor, it is a war waged on multiple fronts.

The challenges are manifold. I had naively thought that all cancer was basically the same disease, with its subtypes just minor variations. But it turns out that there is enormous genetic and chemical variety among cancers, so that a treatment effective for one may do little for another. Indeed, even for a single type—breast cancer, say—treatment can be unpredictable. This is what makes the story of doctor’s attempt to treat the disease so riveting, as it feels like a battle between two equally wily antagonists. At several points in this history, doctors attempt extreme cures—radical surgeries, or nearly fatal doses of chemotherapy—only to be defeated. Meanwhile, the victories can be as modest as a remission of just a few months.

It is probably best not to philosophize about a fatal disease, but there does seem to be a lot of irony in our quest to defeat cancer. For one, it has only become so prevalent in the modern period, because we have started living so long. Its appearance as the great killer, then, is a kind of perverse mark of progress. Further, there is the irony of trying to fight what is, in essence, a corrupted version of ourselves—a group of renegade cells which have figured out how to replicate and survive even better than our own body. There is great scope for metaphor here, but if there is a moral to cancer then I don’t think it is a simple one.

Mukherjee does an admirable job weaving a potentially chaotic and depressing story into something coherent and even hopeful. Though the book is composed of history, science, and his own experience as a doctor, these different threads reinforce one another rather than clash. The clinical anecdotes are sparing—just enough to connect the past to the present—and his thumbnail explanations of science are lucid and illuminating. But, most important, despite the many tragic deaths which litter these pages, the final impression is of how much can be accomplished when a researcher’s diligence, a doctor’s pledge to save life, and a patient’s will to live work together, generation after generation.

View all my reviews

Month: July 2023

Chicago: Sewage and Synchronicity

For years, one of my closest childhood friends, Greg, was living in Chicago as he completed his Ph.D. in history. In the summer of 2021, he was at work on his dissertation, which meant the window to visit him was narrowing. So my brother and I made the journey from New York for a long weekend in the windy city.

As the plane broke through the high, wispy clouds, the city came into view. What was revealed was an astonishingly flat landscape divided into grids as far as the eye could see. We touched down in O’Hare Airport, where we caught the blue line train to the city center. It was a long ride with quite a lot of racket; but complaining about functional public transport in the United States is in bad taste. Slow and loud as it may have been, the “El” trains got us out to Hyde Park (where Greg lives) for a very affordable price. I am grateful.

Since we spent half our time just hanging out, I will not attempt any sort of chronological account of our trip, and will instead simply focus on the major sights we saw while there.

The most logical place to begin is right in the center of the city. Compared with New York, Chicago is a fairly dispersed city, having no natural boundaries to its expansion besides Lake Michigan. Thus, much of Chicago is not particularly dense—indeed, can seem almost suburban in its layout. However, the heart of the city is rivaled in America only by Manhattan in the height and splendor of its skyscrapers.

These buildings are gathered on either side of the Chicago River, which flows through the city center and into Lake Michigan. (It is this river that the Chicagoans dye green every St. Patrick’s Day, to the delight of the fish.)

Or, well, the river is supposed to flow into the lake; but in 1900, the flow of the river was reversed by city engineers. This was a highly controversial move, as it was done because all of the sewage and garbage deposited into the river was flowing into Lake Michigan, the city’s main water source—an obviously unsanitary situation that provoked outbreaks of typhoid and cholera. Through the use of canal locks, the river was made to flow backwards, thus bringing the tainted water via the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (an enormous engineering feat in itself) to the Des Plaines River, which eventually reaches all the way to the Mississippi River.

But you can imagine that, however popular this reversal may have been in the city of Chicago, it was decidedly unpopular for those further downstream. Indeed, in 1906 the state of Missouri eventually took the issue all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of Illinois (though it does not seem especially fair to me).

While we are on the topic of sewage and the Chicago River, there is another story that I must relate. This is the infamous Dave Matthews Band Chicago River incident of 2004, in which a tour bus belonging to the band dumped the bus’s “blackwater tank” (in other words, the sewage) while crossing a bridge over the Chicago River. The driver apparently thought that he could get away with such a maneuver. But unfortunately, the bridge had a grated metal bottom which let the vile liquid through. At just that moment, a boat was passing underneath giving an architecture tour, and the passengers were doused in “blackwater.”

Having said all this, I suppose the fish have more to worry about than green dye.

But to return to my original point, the Chicago River—if not the most appealing body of water—is surrounded by some magnificent architecture. Surely neither you nor I have the patience to go through every single building in the city of Chicago, so I will only mention a few that caught my eye.

One I particularly liked is the Wrigley Building, which features a tower styled after the Giralda in Seville. Built at almost the same time (the 1920s) was the Tribune Tower, which has an elaborate neo-gothic style, with fake flying buttresses adorning the top. Somewhat similar is the neo-gothic Mather Tower, which is so tall and slender that it is sometimes likened by Chicagoans to an upside-town telescope. And completing the rounds of neo-gothic skyscrapers, we have the First United Methodist Church, which looks like a beautiful church spire had been cut off and attached to a bland office building. Of course, the entire thing is not used as a church—but if it were, it would be the tallest church building in the world.

I must begrudgingly mention the Trump Tower, which is one of the most notable buildings in the Chicago skyline. As one might expect of the former president, he wanted to have the tallest building in the world. The plans were considerably scaled back, however, after the September 11 attacks, though Trump’s ego may have been assuaged by the enormous TRUMP sign on the side of the building. (The same architect who designed this building, Adrian Smith, went on to design the Burj Khalifa, which indeed is the tallest building in the world.) On the subject of tall buildings, I must of course mention the big momma of Chicago skyscrapers, the Willis Tower (though you may know it by its former name, the Sears Tower.) This 110-story mammoth is the dominant feature of the Chicago skyline. After it was completed in 1973, it became the world’s tallest building, and held that title for nearly a quarter of a century. It is still among the very tallest of American skyscrapers. The view from the top must be incredible, but the price is pretty steep.

I have left my absolute favorite for last: Marina City. These are two twin residential towers like no other I have ever seen. The aptest description I can think of for these knobby, gnarly, bulging edifices is of two corn cobs. They were built in groovier times—the 1960s—and very much retain a sense of playful fun. That is to say, unlike virtually every “serious” building, there is nothing at all pretentious in this design, and I found myself wondering what it must be like to live in such a whimsical place.

Even with such a brief description, I think several facts about Chicago are immediately evident. Most obviously, if you have any appreciation for fine architecture, then Chicago is a wonderful place to visit. Furthermore, since enormous skyscrapers bearing the names of famous companies do not just spring up from the ground, it is evident that Chicago is an economic powerhouse.

Or at least it was. After hitting a peak of population in the 1950s, Chicago has been steadily losing residents, and it seems possible that the city’s days as a center of finance and industry are behind it. But, as I have learned from my travels in Europe, often the best places to visit are the cities that are past their economic prime. Nobody visits Florence and wishes that it were still a power-hungry city-state. Perhaps it is insensitive to say so, but the diminution of economic development helps to preserve valuable heritage. And, ultimately, such places can be far more pleasant than the crawling ant hills which generate capital.

All prognostications of hope and doom aside, another worthy place to visit is Millennium Park. This park opened as recently as 2004, on what used to be the site of the city’s rail yards. As urban centers in the United States deindustrialize, uses must be found for the old factories and railways which have fallen into disuses. Millennium Park is a wonderful model for how this can be done, for it has transformed a large swath of dead real estate into one of the most popular places to visit in the entire country.

One thing that makes the park so attractive are the works of public art. Most famous is Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate, perhaps better known as “the Bean.” Compared to, say, Michelangelo’s David it may seem extremely simplistic: steel welded together into a bean shape and then highly polished. However, any fair judge of the work must admit, I think, that it is a brilliantly successful work of public art. Walking around this huge, misshapen fun-house mirror brings out a sense of childish delight in many visitors. And residents of Chicago do have a sense of ownership with the Bean, as evidenced by the hilarious series of 2017 fake Facebook events which began with “Windex the Bean.” A great deal of public art—especially abstract, “modern” public art—falls flat, in the sense that residents hardly care about it. But the Bean has come to symbolize all of Chicago, and therefore must be considered exemplary.

Just as delightful, in my opinion, is Jaume Plensa’s work Crown Fountain, which features two large towers of video screens over which water can flow. These towers can show any image. But when I visited, these featured faces of ordinary people “blowing,” with a stream of water emanating from their mouths. Judging from the children who were happily gathered underneath these streams, playing in the water, I think that Crown Fountain must also be considered an exemplary success of public art—art which is fully embraced by the community.

Right next to Millennium Park is one of the greatest attractions in the entire city: the Art Institute of Chicago. Now, before visiting I knew that this was a great museum. But I was frankly unprepared for the quality and size of the museum’s collection. Very few museums in the world are comparable; and in the United States, I believe that only New York’s Met stands on the same level.

The Art Institute has an encyclopedic collection, not only of European paintings, but ranging from Ancient Egypt to the Far East to indigenous American art. More importantly, this collection is of the very highest quality. At every turn I was faced with an intriguing work—sometimes striking or bizarre, sometimes shockingly beautiful, but always interesting and worthy of contemplation. If I had known that the museum would be so excellent, I would have tried to spend more than a few hours there. As it was, I was only able to enjoy the highlights.

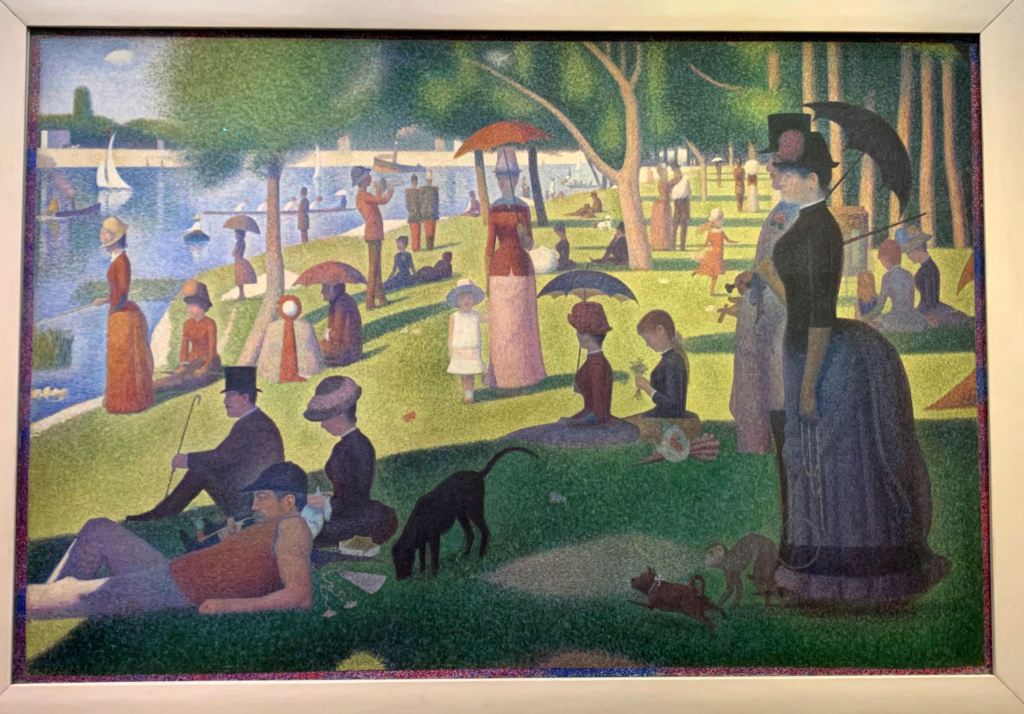

Greg first guided us to his favorite work, a series of stained glass windows by Marc Chagall, which have a soothing, ethereal midnight blue glow. (And I was reminded of how fortunate I am to have comparably beautiful Chagall windows near my house in Sleepy Hollow, at the Union Church of Pocantico Hills.) For my part, I was especially excited to see Georges Seurat’s masterpiece of modernist alienation, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jaffe; and I was surprised and delighted to encounter the American equivalent, Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks. The Art Institute has a strong collection dealing with everyday despair.

But the Art Institute is certainly not limited to negative emotion. From Monet, to Georgia O’Keeffe, to the amazing woodblock prints of Hokusai, the lush beauty of nature is present in abundance. From El Greco’s religious ecstasy, to a statue of the Buddha in meditation, to a ritual knife used by rulers in the Chimú culture, we can see evidence of our preoccupation with the supernatural. There are portraits of rural life (like American Gothic or Monet’s painting of haystacks) as well as urban life (like Caillebotte’s rendering of a Paris street or Delauney’s distorted Eiffel Tower). Compare the locomotive in Monet’s Arrival of the Normandy Train with the one in Magritte’s Time Transfixed to see how the same object can be examined, first, as a sensory impression and, second, as a symbol for the unconscious.

But all of these comments and categories are ultimately just a superficial attempt to come to grips with something whose power lies in its very ambiguity—as is true of all great art. My point is simply that you can hardly come away from the museum without a sense of wonder.

(The Art Institute is featured in my favorite Chicago movie: Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Cameron experiences a kind of existential dread—or awakening, perhaps?—in front of Suerat’s masterpiece, while Ferris and Sloane kiss in front of the Chagall windows.)

I was particularly gratified to learn that the famous 2018 portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama were on loan from the National Portrait Gallery. I had actually missed my opportunity to see them during my 2019 visit to Washington D.C., so it was one of life’s rare second chances. For me, both Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of Barack and Amy Sherald’s portrait of Michelle are well done. They achieve the traditional aim of a portrait, in that they present a likeness of the subject that reveals something of their personality, while also providing a novel twist on the old and tired tradition of oil portraiture. I particularly like Wiley’s take on Barack, in that it emphasizes his thoughtfulness, which I think is his defining quality.

The Obamas are, of course, hometown heroes in Chicago. Michelle has deep roots in the city, having been born and raised on the South Side. And Barack (despite having spent much of his childhood in Hawaii) is identified with the city as well, for it was here that he began his political career. The cult of the Obamas is epitomized in the so-called Kissing Rock. Located in the Hyde Park neighborhood, this is a plaque affixed to a rock, celebrating the spot (approximate, I suppose) where they shared their first kiss. Not far is the site of the future Barack Obama Presidential Library, not yet opened as of this writing.

On the subject of museums, I ought to mention the other major museum we visited on our trip: the Museum of Science and Industry.

This museum is quite far from the center of Chicago, being located on the South Side, near the Hyde Park neighborhood where we were staying. As with many museums around the world, this one is housed in a magnificent building that was constructed for another purpose—in this case, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (basically a world’s fair).

I insisted on going for the simple reason that I had recently watched the classic German war film Das Boot and I felt that I had to see the German U-boat on display. My first impression of the U-Boat was of its size: somehow I had imagined the U-boats would be relatively compact affairs. But U-505 was enormous: 250 feet (76 meters) long, and had a crew of about 50 people. She had an eventful history. After sinking several boats in 1942, she suffered a string of bad luck as she was repeatedly sabotaged by members of the French resistance working at the docks. Finally, on her 10th patrol, she was attacked with depth charges—an experience that proved so traumatic that the captain actually shot himself in front of his crew during the attack. Eventually the U-boat was disabled by the US Navy, who captured the vessel in order to study her.

At the time, I found the experience of seeing an actual German U-boat to be almost awe-inspiring—the chance to see with my own eyes something I had heard about since I was a kid. But in retrospect I am disappointed that we could not take a tour of the interior. Normally the museum offers these tours (for an additional price), but when we visited it was unavailable because of the blasted pandemic. Another casualty of the pandemic was the coal mine. Amazingly, the museum has a large replica coal mine filled with machinery from different time periods, which visitors can tour. But unfortunately for us, as with the U-Boat, the small enclosed spaces make it unfriendly to social distancing rules, and it was closed.

(On the plus side, we did save money this way, since both the U-boat and the coal mining tours cost extra.)

The Museum of Science and Industry is enormous—with exhibits about agriculture and aviation, about weather and math—but only a few things stick out in my memory. One is the beautiful Pioneer Zephyr, the first diesel-powered train in the United States. It has an extremely sleek design made out of glimmering stainless steel, which at the time probably looked futuristic but which nowadays looks retro. Aside from being an attractive vehicle, the Pioneer Zephyr is important in American history, as it helped to repopularize train travel after the Great Depression. It was so streamlined and so fast (it set a speed record between Denver and Colorado) that it was even nicknamed “The Silver Streak” and made the subject of a movie. But my favorite touch was the “observation lounge” in the rear car, which was designed to provide panoramic views as the passengers flew across the countryside.

Another wonderful exhibit was the Great Train Story. This is an enormous model train set, which is a scale model of the journey between Chicago and Seattle. It was obviously made with obsessive attention to detail: at every point in the trip there is something of interest. Though I have no interest in model trains whatsoever, I found myself fully absorbed as I walked around the periphery, following the train as it traversed the “country.” At its best, train travel can be charming and romantic (not to mention efficient), allowing you to glide through landscapes the way a ship sails up a river. And, strangely, the Great Train Story captured that sensation.

That does it for my visit to the Museum of Science and Industry. But I feel I ought to mention the other great museum of Chicago, the Field Museum of Natural History. This is located close to the Art Institute and is one of the great natural history museums of the world. One of my few regrets from the trip is not having visited this institution, as it has an excellent collection of dinosaur fossils.

The most famous of these fossils is the T-rex nicknamed Sue, who is special for many reasons. For one, Sue is the most complete T-rex fossil ever found, with more than 90% of the skeleton (by weight, not by number of bones) accounted for. Sue is also special for having had a tough life. She had broken ribs and a damaged shoulder blade (which healed), holes in her skull from some kind of parasite, and she also probably suffered from arthritis and gout. Sue was one sick puppy. But the story of Sue’s discovery is a drama in itself. Somehow, it involved an FBI raid and the leader of the fossil expedition being sent to prison. To top it all off, when she was sold to the Field Museum, Sue fetched the highest price of any dinosaur fossils ever found up to that time ($8.3 million in 1997, which would be about double that today). She is worth every penny.

This pretty well does it for my time in the center of Chicago. But during our visit we spent most of our time, not visiting the main sites, but in Hyde Park with my friend Greg.

A student of the University of Chicago, Greg naturally lived quite close to its campus. One day he gave us a little tour as we made our way to a farmer’s market. As we walked through it, I found the manicured, neo-gothic campus to be both beautiful and strangely familiar. This deja vu was due, I think, to the college’s architecture being influenced by the taste of its founder: John D. Rockefeller. I grew up in the shadow of Rockefeller’s estate, so by now I can recognize his preferred aesthetic: neo-gothic, molded out of gray granite. This is especially evident in the monumental Rockefeller Chapel, the dominant structure of the campus, big enough to seat 1700 people. Compare it to another great Rockefeller church, the Riverside Church in Manhattan, and the similarities are unmistakable.

As we walked, a question popped into my mind, seemingly out of nowhere:

“Greg, what do you think is the most beautiful college campus in America?”

He thought about it and answered: “Pepperdine,” mainly because of its prime location on a hill overlooking the Californian coast.

We arrived at the farmer’s market and I proceeded to stuff myself with artisanal meat pies. But I had a shock when we went up to a fruit stand and the vendor said to Greg:

“You get a free banana if you answer this question.”

“Shoot.”

“What’s the most beautiful campus in the United States?”

“Pepperdine.”

And he got his free banana.

This is one of the most striking examples of synchronicity—uncanny coincidence—that I can remember. The chance that the fruit vendor would ask the exact same question that had popped into my head five minutes prior seems remarkably low. If this was an act of God, I suppose He really wanted Greg to have that banana.

I should also mention our trips to the lake. After just a short walk, we found ourselves on a lovely sand beach on the shore of Lake Michigan. The water was cool, calm, and—best of all—free of salt. (Not that I would drink it, but at least it doesn’t hurt if it gets in your eyes.) And unlike many urban beaches I have visited, it also wasn’t overcrowded. It made me realize how unfortunate residents of Madrid are not to have a water feature nearby. Swimming was wonderfully refreshing after a day of trekking around in the heat. We went on three separate occasions during our four-day trip, and I can easily imagine becoming a regular during the summer months.

This part of the city does have a major attraction: the Frederick C. Robie House. Completed in 1910, the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and commissioned by an assistant manager who was just 28 years old (this is when the real estate market was kinder, it seems). Poor Fred Robie did not, however, get to enjoy the fruit of his wealth and taste for long. After just fourteen months, a combination of his dissolving marriage and inheriting his father’s gambling debts made him have to sell the house. The next owner, David Lee Taylor, wasn’t any luckier, as he died less than a year after moving in. Eventually the house ended up in the hands of the Chicago Theological Seminary, who used it (rather sacrilegiously) as a dormitory. The clergymen even planned several times to demolish the building in order to construct a bigger building for their students, and the nonagenarian Wright had to get involved in the protests to stop it.

Nowadays, the Robie House is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, so it is well out of danger. It has also been largely restored to its original condition. To visit, you need to sign up for a tour, which required no previous reservation when we visited.

This was the first (and so far the only) Wright house I visited, so I did not know what to expect. My only experience of an architecturally notable home is the Casa Batlló, in Barcelona, which was designed by Antoni Gaudí. Compared to the Catalan architect’s intricate and exuberant style, Wright’s design seemed extremely restrained. However, as the tour progressed, I began to appreciate the cohesive vision that tied together everything from the brickwork, to the light fixtures, to the furniture. Everything was of a piece. The horizontal is consistently emphasized over the vertical, making the house seem short, flat, and stretched out. Unlike in Gaudí’s work, right angles abound, which gives the space a kind of crisp mathematical precision. The palette of earth tones that characterize every surface in the house almost make it seem as if the house sprung out of the ground. I especially liked the designs on the stained-glass windows, which are ornamental without being ostentatious.

The guide, who was excellent, recited several of Wright’s more pugnacious quotes about architecture, such as “Modernistic houses are more boxes than houses.” Wright clearly had his own ideas about how a building should be put together. But I must say that, however beautiful the house may have been, I did not find myself wishing I could live in it. The Wright furniture was stylish but did not seem comfortable, and the balanced rooms did not have enough available space for my liking. Also, I imagine that the many large windows make it quite difficult to heat in Chicago’s brutal winters. Maybe this is why the priests wanted to replace it. I wouldn’t want to live in a work of art.

This pretty much rounds out my experience of Chicago’s main sights. To conclude, besides our visit to the city’s gay neighborhood (Northalsted) to spend time in a fun bar with arcade games, I should mention the food. Naturally, we had to try Chicago’s most iconic dish, deep dish pizza. My mom actually went to school in the city and cooks deep dish at least once a year, so I do not have the typical New Yorker’s scorn for this style of pizza. Deep dish really isn’t very comparable to a “normal” pizza, anyway; it is more like a casserole. But if you accept it for what it is, I think that it is extremely delicious.

The other iconic Chicago food we had were the hot dogs. These are traditionally made of beef and topped with pickles, pickled peppers, onions, tomatoes, mustard, and celery salt. I was a bit skeptical of having so many toppings, but it may have been the best hot dog I have ever had. The many sour and acidic ingredients help to balance the greasy, meaty flavor of the frank, making for one perfect gustatory experience.

My biggest regret from the trip is that we didn’t visit one of the city’s many blues bars. The only other time I have been in Chicago was when I was 17 years old, visiting colleges with my aunt and uncle. They were kind enough to take me to a blues bar and I remember loving it. Indeed, I bought the band’s CD and listened to it for weeks afterwards. But this was 2021, COVID times, and we deemed it too risky to go into a crowded bar. I suppose I will just have to return to the windy city.

After a final swim in the lake, my brother and I got on the El and made our way to the airport, where we wolfed down some Chinese food and awaited our flight back to New York. It had been a great trip.

Review: The Path to Power

The Path to Power by Robert A. Caro

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Last winter, I went to the Film Forum in Manhattan with some friends to see the new documentary about Robert Caro and his famous editor, Robert Gottlieb. It was a wonderful experience on many levels. The documentary was fascinating and inspiring—the story of two people who, in quite different ways, have lived fully dedicated to literature—and it was the perfect place to see it, in the heart of Caro’s and Gottlieb’s city, surrounded by other New Yorkers.

Gottlieb comes across as a lovable and brilliant person (he has, sadly, since passed away at the age of 92), but Caro comes across as something superhuman, an embodied intellectual force. The name of the documentary, Turn Every Page, aptly summarizes what makes Caro so special: the meticulous, obsessive, even demented attention to detail—the determination to get to the heart of every aspect of every story, to never be satisfied with half-truths or empty explanations. And then, once he has gathered together his facts, this relentless attention is focused on the writing. For Caro is not satisfied with merely presenting us with his (always impressive) research. He is determined—again, maniacally so—to make us understand on a deep emotional level what each of these facts mean.

All of these qualities are fully on display in this, the first book of Caro’s monumental biography of the 36th president of the United States. As a political biography—a record of the accumulation and use of power—the book is peerless. Caro traces how Johnson, by sheer force of his personality, went from a rural boy with little education and less money to a member of Congress in just a few years. His chapters on Johnson’s elections alone—his campaign strategies, his fundraising, his advertising—are a goldmine for any political historian, and eye-opening for even the most cynical of readers.

Yet everybody knows that Caro is a master of political biography. What surprised me most was how brilliant this book was in other respects. His descriptions of the Texas Hill Country, for example—its climate, its soil, its weather—often rise to such a level of poetry that I was reminded of John Steinbeck. And his chapter on life in the Hill Country before electrification—the difficulty of even simple chores like washing and ironing—is so empathetic that it brings this experience to life as powerfully as even the most gifted novelist could manage.

Aside from this wonderful scene-setting, and aside from the incisive history, this book is of course the study of a personality. And it is a peculiar one. Indeed, underneath all of the historical detail, I think there is a very basic moral conundrum at the heart of this book. It is, in short, that Johnson is successful and effective—indeed, often a force for good—while being personally unlikeable and morally vacuous.

Caro goes to great lengths to illustrate the uglier sides of Johnson’s character. His urge for power is so great that it trumps every other consideration in his life: love, loyalty, ideals, friendship, ethics. When he is stealing elections, betraying friends and allies, and cheating on his wife, not once does he give evidence that he even possesses a conscience. And yet, in his quest for power, he educates children, helps the unemployed find jobs, secures money for veterans, and electrifies his district, among much else.

This paradox is illustrated in Johnson’s treatment of his secretaries. While he worked as a congressional assistant, Johnson went to great lengths to help the constituents of his district—far more than any ordinary assistant could or would. But this unusual effectiveness was achieved by working his own secretaries to such a degree that they could not have any life outside of work, and one had a nervous breakdown and fell into alcoholism. This is a consistent pattern: the specific people close to Johnson are used as tools for his own advancement, while the abstract people out in the world benefit from his obsessive work ethic.

To put the matter another way, Johnson seems to violate every ethical precept I know regarding the treatment of others, and lives in total contradiction of every piece of advice I know regarding wise and good living. Johnson comes across as a miserable person destined to share his misery with the world. But it becomes clear that Johnson’s personality type is perfectly suited for politics, and he achieves almost instant success when he enters that field. Indeed, one gets the impression that everyone else in Washington D.C. is just a toned-down version of Johnson—equally as power-hungry, but not as effective.

Somehow, we seem to have a system designed to elevate people whom most of us would find repulsive. Maybe this is inevitable, as the people who most desire power are the ones most likely to get hold of it. Perhaps the best thing to do, then, is to hope that the institutions are set up in such a way that, as in the case of Johnson, these driven individuals end up having beneficent effect on society. And yet, this does seem like an awfully risky strategy.

In any case, as I hope you can see, this is a superlative book, excellent on many levels. It is, in fact, among the select class of books that can forever change your outlook.

View all my reviews