I arrived at my Airbnb late—almost midnight—after illegally riding the bus to the outskirts of the city.

I can never get used to these transport system where there are no turnstiles for the metro and where you cannot simply pay the busdriver. Instead, you must buy a ticket beforehand and validad it yourself. This makes the temptation to ride for free very difficult to resist, especially if it’s late and you don’t know where the ticket machines are. In Madrid or New York, if you try to ride a bus for free the driver will kick you off; and if you jump the turnstiles you can get a big fine. But in Amsterdam, you will only face consequences if the metro inspectors catch you. And what are the chances of that?

My Airbnb host was a relaxed fellow. I suspected that he enjoyed the free availability of marijuana in the city. In any case, he very kindly offered to lend me his museum pass, which allows any resident of the city to get into the museums for free. Unfortunately for me, I had foolishly planned ahead and bought my museum tickets online. The money was spent—and for nothing. This was the last time that I travelled responsibly.

It was a cold February night and I was hungry for dinner. The only place open was a kebab restaurant—not fast food, but genuine kebab. It was delicious. Biting into the spiced meat, I knew that Amsterdam was going to be a special place.

§

I woke up early the following morning and set off for the Van Gogh museum. Instead of riding illegally again, I decided that I would take the time to walk through the city. The weather was cold, grey, misty, and threatening rain. Despite the circumstances, however, and even though I hadn’t had breakfast, the city immediately caught my attention.

Amsterdam is among that small class of cities whose every avenue announces its identity. Even outside of the historic city center, it is impossible to forget that one is in Amsterdam. For one, there are the bicycles. There are thousands of them—hundreds of thousands. It is said that there are more bikes than people, and what I find online seems to confirm it: the population is around 820,000, while there are over 880,000 bikes. Why anyone would need more than one bicycle, I can hardly guess. Nonetheless it is an inspiring sight. Every corner of the city is crammed with pedalled contraptions; and there is more traffic on the bike lanes than on those for cars. But pedestrians have an extra worry when crossing the street.

The style of architecture is distinct, too. In the center there are the crow-stepped gables—creating the Netherlands’ distinctive skyline. Also distinctive is the use of brick. Everything seems to made of the baked clay blocks, giving the city a dark, brooding, and quasi-industrial feel. Certainly it is impossible to mistake a single street of Amsterdam for one in Madrid.

But perhaps the most distinctive touch of Amsterdam are the canals. Like much of the Netherlands, the city itself rests on what was previously swampland. The canals were used to redirect the water, thus making the land available to build on while providing convenient transportation within the city. The canals have also, historically, been useful in the city’s defense. The Stelling van Amsterdam is a system of forts surrounding the center, with low-lying ground that can be flooded to create a watery barrier too shallow for boats. Unfortunately for the Netherlands, this system of defence, however elegant, was rendered obsolete by advances in military technology—such as bombers.

Nowadays, the canals are mostly just pretty to look at. And they are plentiful. There are 165 canals, which is more than even Venice has; and well over a thousand bridges are needed to connect all the isles of land floating between them. Personally I found the constant presence of running water to be extremely charming. The canals make the whole city seem to breathe in the open air, counteracting the somewhat cramped aspect of the city’s narrow buildings.

The final result is a beguiling mixture: wide vistas and narrow alleys, crowded footbridges and bustling bike lanes, historic brick husks concealing modern interiors.

As I walked, listening to the soundtrack of Phantom Thread, I was lost in an aesthetic reverie—marvelling at every new perspective afforded to me. Each shop window and city street gained a strange significance, each one a kind of monument to past and present lives. The cold and the dark gave the city a melancholic hue; but it was a sweet sadness, the kind of sorrow one feels at all beauty, knowing that it is temporary. This, then, was my first and final impression of Amsterdam: the beauty of everyday life.

§

My first stop was the Van Gogh Museum.

Few museums dedicated solely to the art of one man can be ranked among the great museums of the world, but this is one of them. The institution is situated in a sleek, modern building in Museum Square. The museum received its collection—the largest in the world of Van Gogh’s works—from the artist’s family. After Vincent and his brother, Theo, passed away, his unsold work fell into the able hands of Theo’s widow, Johanna. She, in turn, left the collection to her son, named after his uncle, Vincent. The museum only opened its doors in 1973; before that, Van Gogh’s works were held and displayed in the state modern art museum, the Stedelijk.

No photographs are allowed inside the museum, which is likely a good thing, since otherwise there would be far too many selfie-takers clogging the halls. Thus, I will have to rely on my memory. On the ground floor there is a series of Van Gogh’s self-portraits. His oeuvre is particularly rich in self-portraits, perhaps because he was prone to melancholy self-examination, or perhaps because he simply could not afford other models. In any case, they are milestones in the history of art: an attempt at introspection whose nearest literary equivalent is, perhaps, Montaigne’s Essays. When the portraits are arranged chronologically, one can see the progression in his style, from lumpy forms of dull browns and greys, to bright blues and yellows in dashing lines. His best self-portraits achieve a mesmerizing stare about the eyes, comparable to the intensity in Michelangelo’s David.

Next, the visitor ascends the stairs to enter the main collection. The exhibit begins with some of Van Gogh’s influences. One of the most important of these was Jean-François Millet, a French social realist who often painted rural scenes. Van Gogh was himself a passionate believer in painting from life; and in his early years especially he was fascinated by poverty and peasant ways. Many of his early sketches (which are on display) are of workers in a field or townspeople attending a mass. Van Gogh got a relatively late start in the craft (27, which is good news for the rest of us) and his early work displays no technical brilliance, to say the least. But it does show, if my eye may judge, a keen emotional sensitivity to the world around him, especially to the toil, drudgery, and misery of life. There is nothing in his work that can be called frivolous.

I came well prepared, since I had just finished reading a collection of Van Gogh’s letters (highly recommended). You may imagine, then, how much of a treat it was to see the artist’s work laid out chronologically after I had worked my way through his life. Again, what most strikes the viewer about Van Gogh’s early work is its lack of color. He seems to have had almost no interest in pigment. This is epitomized in his early masterwork, The Potato Eaters. He shows us a scene of peasants eating a humble meal. It is not an inspiring sight. The men and women have heavy, almost simian features, reminiscent of Goya’s black paintings (though I do not think Van Gogh ever saw them). The oil lamp illuminates the hovel with a sickly light, which reinforces the ill and withered look of the painting’s subject. Van Gogh shows us an ugly truth, horridly naked, and yet made monumental in its composition.

Vincent’s style underwent a dramatic change when, after enduring years of isolated poverty and estrangement with his family, he moved in with his brother, Theo, in his Paris apartment. Theo was an art dealer, and Paris the art capital of the world, so Vincent was well-positioned to take stock of the dominant artistic currents of his time. In Paris he saw the work of modern masters like Monet, Seurat, and Cezanne, and befriended many other prominent artists (most famously Gauguin, who later came to stay with Vincent until they had a quarrel). The most immediate consequence of this exposure was Vincent’s discovery of color. Compared to his earlier work, the paintings he started to produce were bright and joyful, though still burning with intensity.

I would also like to add a curiosity I learned on my visit: that Van Gogh was enamored of Japanese art. Like many artists of the time, he collected Japanese prints. He even went to far as to copy them, producing his own versions of works by Hiroshige. His copies, though lacking the lightness and clean execution of the original, are well done. And he even went so far as to write Japanese all around the border of the painting (though I don’t know if it is proper Japanese, since I do not think he could read the language).

Unfortunately, Van Gogh’s years in Paris are some of his worst documented, since he was living with his brother and so had no need to write him letters. Nevertheless, it is clear that the artist was busy practicing his craft. The Van Gogh museum even has a study that he made of an object (I remember it was a small statue of an animal, but I cannot remember which). Van Gogh’s distinctively heavy brushstrokes also begin to make their emergence at this stage. In another room, a recreating of one of his paintings is on display under a microscope, so that the visitor can see the swirling textures of the master’s paint up close. This habit of daubing on pigment in glooping quantities caused his paintings to have an almost sculptural feel, something that no poster or print can capture.

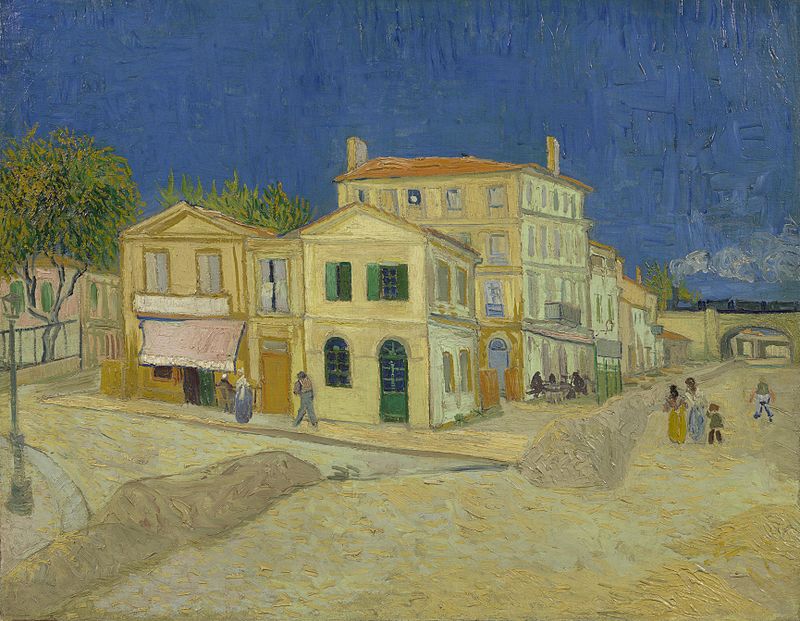

After two years Van Gogh left Paris for more the amiable climate of southern France. Here is when his real mature period begins. While his early works tend to focus on humans in action, his mature style was more focused on scenes: buildings, rooms, landscapes. One painting which epitomizes the change is The Yellow House, depicting the building in which he rented an apartment with the naive hope of turning it into an artists’ colony. Far from the center of focus, the people in the work are anonymous shadows, only serving to illustrate the city street that is his main focus. Van Gogh also painted his room. Here the painter’s expressionism is especially obvious. The perspective is warped; it is not quite believable as a space. But the bold yellows and light blues convey a sense of joyfulness and peace, which is nevertheless somewhat belied by the faint whiff of poverty one senses from looking at the barely furnished room.

But Van Gogh’s most famous painting from this period is likely the Sunflowers. Van Gogh made multiple versions of this painting; the most famous of these is at the museum. It is a masterpiece. The painting has the strong and instantly memorable visual impact of the best graphic design. Yet it is better than any design, of course. With his thick and skillful dabs of paint, Van Gogh makes the sunflowers almost tactile. Though more abstract and more beautiful than any real sunflower, one almost feels that she can reach into the painting and grab one. But the emotional effect of the painting goes far beyond its obvious visual properties. As in all of Van Gogh’s best work, the dominant feeling is joy, immense joy, struggling with and overcoming equally intense feelings of despair. During his stay at the Yellow House, Gauguin created a valuable image (also at the museum) of Van Gogh at work on the sunflowers.

Needless to say his dreams of founding an artists’ colony failed. Van Gogh was hardly the figure to command a movement, not least because he was tetchy and unyielding. For example, he constantly clashed with Gauguin over the necessity of drawing from nature. Gauguin believed in letting the artist’s imagination run wild, free of constraint, but Van Gogh insisted that great art only resulted from close observation. In any case, their falling out had as much to do with Van Gogh’s worsening mental state as with his opinions. According to Gauguin, Van Gogh attempted to attack him with a razor; later this same night was when Van Gogh famously severed his ear.

This led to Van Gogh’s hospitalization and eventual suicide—and also to the most productive and extraordinary phase of his career. It is still unclear what ailment plagued the artist in his final years. His lifestyle—smoking and drinking heavily, frequenting prostitutes and possibly contracting syphilis, eating scantily and sleeping sporadically—no doubt contributed. The museum has a display of various hypotheses: Freudian theories of repression, bipolar disorder, sunstroke, digitalis poisoning. Likely we will never know for certain. Whatever the explanation, Van Gogh struggled heroically with his worsening condition, creating an oeuvre that rivals any in the history of art.

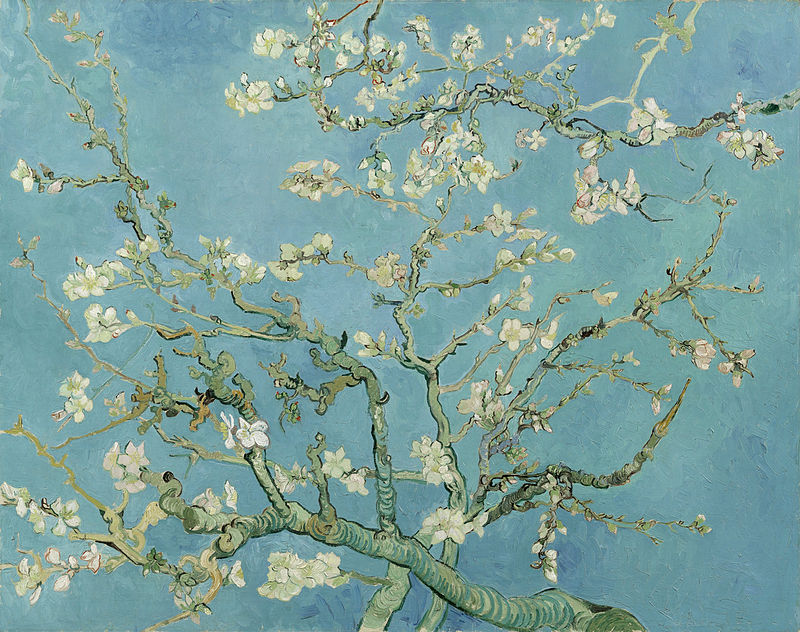

One of these remarkable late paintings is his Almond Blossoms. The twisted branch of an almost tree in bloom stretches across the canvas. Beyond is the blue sky, as if the viewer is below and looking up at the boughs. It is a painting of extraordinary calm. One wonders how a man recently admitted into an asylum could conjure such a tranquil image of nature in its simple beauty. And here, once again, we see the artist’s talent for reproducing the emotional effect of nature, rather than nature herself. For the painting is impossible to mistake with a photograph; the brush marks are visible, the flowers are not finely detailed. Yet the painting gives the sense of lying on grass, looking up at an almost tree—the cool breeze, the gentle sun, the fresh smell of spring—better than any photograph can.

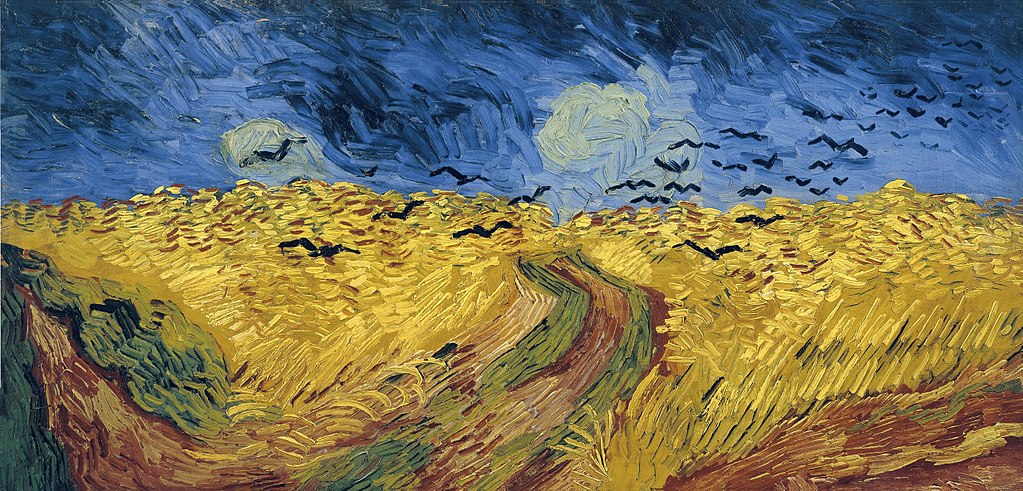

Among the final paintings on display is Wheatfield with Crows. This is commonly said to be Van Gogh’s last completed painting—though no reliable record exists of it being so—and so critics are apt to see in it signs of depression. Certainly these are not difficult to find: the brooding, stormy sky; the windswept field; the black birds heralding death—and all in a style of extraordinary intensity. But to me this is not the work of a man tired with life, bent on leaving this world. Indeed, though it is hard to argue that the painting is happy, I still sense in it the same joy that one feels in Sunflowers: the awe in the face of a natural spectacle, the wonder at the basic scenes of everyday life. That the same man who painted this would, shortly later, shoot himself in a similar field, beggars my imagination.

Van Gogh’s self-mutilation, confinement, and eventual suicide form an essential part of his myth. No doubt he was dogged by a serious illness, which at times sent him into delusional fits. Yet it is very much disputable the role that Van Gogh’s mental illness—whatever its cause—played in his painting. Some have argued that it contributed to his creativity, giving him a unique vision. One can equally well argue that his art was a way of staying sane and fighting off his demons. Personally, I am averse to this modern tendency to diagnose everyone who seems odd, different, or eccentric with a mental disorder, equating different forms of genius with conditions or illnesses. Such diagnoses strip the individual of his agency, and even of his individuality. More importantly, post mortem diagnoses are impossible to prove.

This did it for the Van Gogh Museum. I can say without hesitation that it was one of the most extraordinary museums that I have had the pleasure of visiting. Fortunately, another one was just around the corner. So after a quick sandwich in Bagels and Beans—a local chain, very tasty—I was on my way to Amsterdam’s other major museum: the Rijksmuseum.

§

The Rijksmuseum is the Netherlands’ national museum, comparable to Louvre in Paris or the Prado in Madrid. Founded in 1800, the museum is located in a grand, palatial building—appropriately Dutch in design—right in the center of the city. In it can be found some of the finest examples of Dutch art, including many famous paintings by the Dutch Golden Age masters. It is a necessary visit for anyone with even a passing interest in the history of art.

Aside from a small collection of Asian and Medieval art, the museum’s collection really begins in force with the Renaissance. Here we see the beginning of portraiture as we know it: the attempt to capture the personality of one ordinary individual through a close concentration on their features. We see characters of various sorts—the proud, the crafty, the self-indulgent, the vain—at times ridiculous, yet rendered iconic through the painter’s brush. It is one of the great mysteries of art that it can transform the unique into the universal by emphasizing what is most unique. Perhaps this is because we are all different in the same ways.

The museum does not only contain paintings. There are also ornate chess-sets, statuettes, altarpieces, and even what were supposed to be unicorn horns (in reality, the tusks of narwhals). And there is a fascinating section devoted to colonial art—both art collected from, and inspired by, the Dutch colonization of the Indies. Here we find ornate cannon barrels, one with the head of a dragon, as well as small dioramas depicting colonial life. Also on display are delicate luxury items, such as furniture, candelabras, and mirrors—even an ornate harpsichord. Nearby are the 19th century paintings, among which are excellent examples of Dutch landscapes and portraits.

Yet the museum’s most valuable treasures are gathered together in the Gallery of Honor. And just as Velazquez’s masterpiece, Las Meninas, occupies pride of place in the center of the Prado, so does Rembrandt’s iconic The Night Watch dominate the central gallery.

This painting is justly famous for its revolutionary take on a group portrait. Traditionally, a portrait of this kind—not of nobles, but of the local militia—was a formal and static affair, with the participants lines up in rows according to their rank. Rembrandt cracks this convention wide open with this work. Every person is individualized, and everyone is engaged in some sort of action. As a result the group portrait is full of bustle and even confusion, as each character is busy loading their riffle, having a chat, or gesticulating heroically. It is difficult to imagine this chaotic rabble of men marching in formation, but easy to imagine them relaxing in a pub. Only a master of portraiture such as Rembrandt could have put together such a marvelously memorable image out of such seemingly unpromising material. And if any evidence was needed of his technical ability, examine the foreshortening on the lieutenant’s spear in the foreground.

Another, somewhat lesser-known master of the Dutch Golden Age was Jacob van Ruisdael, who was the preeminent landscape artist of the period. One might think that the Netherlands is an unpromising land for landscape painters, since the Dutch countryside is so flat and domesticated. But Ruisdael has shown us otherwise. Personally I find his use of color and texture mesmerizing: the fluffy clouds floating in the light blue, the varying greens of the trees and the dull browns of the dirt—it all comes together in such a way that the ordinary beauty of daily scenes emerges. I particularly like his Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede for its brooding, grey sky silhouetting a lonely windmill—perhaps an ironic comment on the force of technology as compared to that of nature.

My favorite painter of this period, and the one that most perfectly captures my impression of Dutch life, is Johannes Vermeer. Here we see something almost entirely new in the history of art. Rather than focus on the forces of nature, the royalty, aristocrats, or wealthy merchants, we have a focus on the most absolutely ordinary of daily, domestic scenes. The most famous example of this is The Milkmaid, which shows us a serving woman engaged in pouring milk. Again, it is the most typical and unromantic of gestures; and yet Vermeer, with his fine attention to daily, manages to imbue into this gesture an extreme pathos—an elemental poetry.

Another one of my favorites is The Little Street, which shows us a typical, middle-class street in the city of Delft. The buildings are in the homely, Dutch style, made with step-gabled roofs of brick, and they are a little bit worn by the weather. Inside Vermeer allows us to spy on a woman at work, washing clothes. Nearby, seated in a doorstep, another woman is sewing; while two children are searching for something (or playing a game?) underneath a bench. Again, the painting is poignant for its very ordinariness. Vermeer shows us the quiet nobility of these neighborhood scenes, normally taken for granted and yet necessary for life to go on. And in the process the artist has created an image more impressive than the full-length portrait of Napoleon, dressed in the most pompous of imperial outfits, in another gallery of the museum.

In a word, I found in the Rijksmuseum what I had also found in the Van Gogh Museum, and indeed in the city itself—a celebration of the beauty of everyday life.

§

My next destination was Amsterdam’s infamous Red-Light District. This is so-called because of the red lighting used to advertise a prostitute’s service at night. The area is famous, not only for the working women displaying themselves in shop windows, but also for the many peripheral sex-related businesses: sex shops, sex shows, and even a museum of prostitution (which was what I decided to visit).

Ironically, perhaps, the red-light district in Amsterdam is in the most historic and beautiful part of the city. Canals criss-cross this side of town in a circular pattern, making all foot-travel a labyrinth of alleys, narrow streets, and foot-bridges. Hardly a street goes by that does not reveal another picturesque view of the city. It was a clear February afternoon, with the blue sky gradually turning pink in the sunset, and shadows gradually extending across the canals. I was there before dinner, so the area was fairly quiet. Indeed, apart from a few signs, it was difficult to know that I was even in a red-light district. No scantily clad women graced the windows overlooking the street. This meant that I could take pictures without fear. From what I hear, the women get angry when people photograph them, and may even leave their perch in violent pursuit.

Before I relate what I learned in the Museum of Prostitution, I wish first to cover another of Amsterdam’s famous markets: marijuana. Now, you may be surprised to learn that marijuana is not legal in the city; it is decriminalized—or tolerated, in other words. The result is the same, however: a visitor may consume weed without fear of the police, and even buy small quantities with impunity. This is normally done in “coffee” shops. I did not visit one of these during my stay—I was traveling alone, so it didn’t seem like a good idea—but I have heard ample stories of friends smoking too much, or eating too much of an edible, and repenting afterwards. Well, maybe next time.

The Museum of Prostitution is dedicated to Amsterdam’s other great vice: sex. It is right in the center of the red-light district, in a space that was formerly used by call girls. The ticket came with an audioguide, in my case narrated by a Russian sex worker. The museum itself is designed to replicate the spaces used in these circumstances, complete with bathrooms, beds, and chains. I learned some interesting facts along the way. The standard deal is to pay €50 until the man finishes—which normally takes less than 10 minutes. A working girl makes more money with a faster turnover, you see. The guide also told us about some of the dangers that prostitutes face, even in a highly regulated industry like Amsterdam’s, as well as some amusing stories about customers. Really, the most striking thing about the museum was how un-sexy the experience is made to seem, for both client and purveyor.

I especially appreciated the information about prostitution throughout the world. In most of the United States it is absolutely illegal. In Spain, it is decriminalized to be a prostitute, but pimping is illegal. In France it is legal to sell sex but illegal to buy it—a curious situation. In Amsterdam it is highly regulated, with a certain number of legal permits. Window prostitutes only constitute a moderate portion of the business in the country, with street walkers, sex clubs, and escort services rounding out the rest of the market. I have heard people say that STD testing is mandatory, but this is not actually true—though I am sure that many prostitutes regularly get tested, and condom use is universal.

Unfortunately, despite the increase in legal protections, the industry is still rife with problems. Prostitutes are far more likely to suffer abuse or rape. And since prostitution is still illegal in much of the world, and in any case there is a lot of money to be made by unscrupulous people, human trafficking, especially of underage girls, is still a serious problem. This has led to some crackdowns by the authorities. Coffee shops have not escaped this legal limbo, either, since although it is not illegal to buy or possess marijuana in small quantities, it is illegal to grow or buy it in large quantities—which leads one to wonder where these coffee shops get their supplies.

Though I was not inspired to try it for myself, I left the museum greatly impressed by the huge and so often ignored role that the world’s oldest profession has played, and still plays, in society. To pick a relevant example, Van Gogh was a dedicated patron of brothels. At one point he decided to live with a prostitute and her young child—despite the protests of his family and friends—and after his self-inflicted wound to the ear, he delivered the severed appendage to a local prostitute. And this story is just one of millions.

Sex work has been a constant presence in the history of every nation; yet this indecorous profession has consistently been pushed into the shadows. It is something we prefer to ignore, even if we all know it exists. Personally, despite its shortcomings, I think that the Dutch approach is far better than American prudishness. If we simply admit that, one way or another, sex work will continue to exist, we can install the necessary safeguards to make it safe for its practitioners. Pretending it does not exist only serves those who prey on the vulnerable.

§

I only had a long weekend to spend on this trip; and I had decided, perhaps too ambitiously, to visit both Amsterdam and Brussels in the three full days I had available. This meant that, after my long day exploring the treasures of Amsterdam, I had to catch a train the following afternoon. Only the morning remained to see more of this enchanting city.

I decided that my time was best spent in renting a bicycle. Amsterdam is one of the most bike-friendly cities in the world; and if you want to see the city from the perspective of a native, this is the only way to do it. So I trekked from my Airbnb to Centraal Station (listening to Frankenstein on audiobook, whose dark gothic tone did not quite match the bourgeois beauty of the city), deposited my big orange backpack in a luggage locker (they are located beyond the train turnstiles), and rented a bike from a place called MacBike (no relation to Apple).

It was a simple contraption with a few gears and decently working brakes. Somehow, while I was adjusting the seat for my overlong legs, I cut myself in my palm. It did not hurt at all; in fact I didn’t notice until after several minutes of riding; but it bled quite a bit and the scar lasted for months. Thus I bloodily made my way into the city. I was quite nervous at first. My riding skills are reasonable, but I felt intimidated by the rules of the road. I had never signalled, passed on the outside lane, stopped at a stop sign, or dealt with intersections on a bike. And I can hardly do those things in a car in any case. But once I got my biking legs back, I felt marvelous as I drifted down the historic city streets.

Bicycles are one of the most extraordinary inventions our species has blundered upon, and I think many cities could be vastly improved by following Amsterdam’s example and relying more on bike transport. They require no fuel except the food you eat, are fast enough to quickly navigate most city centers, need little space to store, produce no pollution, and as an added bonus promote healthiness and well-being. I remember watching a presentation by Bill Nye while I was in high school in which he told us that bicycles are the most energy-efficient form of transportation known to man. They are also quite relaxing and enjoyable.

As you can tell from this paean to bicycles, I was having a splendid time. But it was difficult to navigate the city, since I couldn’t follow any maps on my phone while I was riding. After several wrong turns and detours, then, I found my way to Vondelpark, a very pretty green space with twisting paths for walking and biking, and a little pond running down the center.

As I rode through this park, I had one of those surreal moments when one seems to be seeing oneself from a distance. I had heard of people visiting Amsterdam and renting bikes back when I was in high school, but never did I imagine that I might do the same thing myself one day. Yet here I was, less than ten years after graduating high school, pedaling around in this beautiful foreign city before my train left to Belgium—another place I never imagined that I would visit. It seemed too good to be true, like I was living somebody else’s life. This was an irrational reaction, since it is not as if biking in Amsterdam is objectively more pleasurable than biking in, say, my old university. What made it special was that, throughout the years, I had unconsciously invested the experience with an exotic, unreachable quality; and now I was finding that, far from unreachable, it was the easiest thing in the world.

In an hour I had arrived back in the train station. It was to be my last glimpse of the city before my ride to Belgium. The experience only confirmed what was, from the start, my constant impression of Amsterdam: the appreciation of ordinary pleasures, the celebration of daily beauty, the quiet contentment with the simple things in life. It is a city of high culture but of little pretense, of hard work yet of an easygoing attitude. I hope to return someday.