The Middle Rhine is majestic and impressive, but it is not exactly tranquil. There are barges and ferries full of tourists constantly running up and down the river. There are small villages, yes, but they are often crowded with visitors. During my visit, an American fighter jet even flew over the river valley. The Middle Rhine, in other words, for all of its beauty, is not a trip to the countryside for a bit of scenery and fresh air.

But its little brother, the Moselle, is wonderfully sleepy by comparison. Joining the Rhine at Koblenz (of which, more later), the Moselle seems to flow lazily along when compared to the mighty current of the Rhine. Rather than being surrounded by steep cliffs and towering hills, the land gently rises into green knolls, all of them covered in vineyards.

I observed this gentler valley as my train traveled from Koblenz, and was immediately charmed. My destination was the little town of Moselkern. I had arrived early, and the town was so quiet that it almost seemed abandoned. Nothing was open, and nobody was on the street. But I did notice some silly pieces of doggerel printed on the sides of buildings. In front of the Hotel Kebstock, for example, I read this:

Mein lieber Gast,

laß dich

Nieder mache Rast

Bei Bier und Wein,

bring Glück herein.

An der Mosel

und am Rhein,

trinkt man

den guten Wein.

In essence: “Come on in, drink some wine, and have a rest.” It certainly sounded appealing.

But I couldn’t stay for long, for I was not visiting Moselkern to see the town. Rather, as I had been doing so often on this trip, I was there to see a castle: Burg Eltz.

As you may know, most castles everywhere are situated in or near a town, normally on a piece of high ground. This particular castle, however, is not in any town, but right in the middle of a forest. To get there, in other words, I had to take a hike.

I marched out of Moselkern headed northwest, following the Elzbach, a little stream that empties into the Moselle. Very soon I found myself completely surrounded by woods. It was marvelous. As I have had occasion to say many times on this blog, one thing I miss about New York is the lush greenery of its forests. For all of its beauty, most of Spain is relatively dry and arid, the landscape yellowish and bare. Thus, I intensely savored the sensation of being, once again, in a dense, green wilderness, surrounded by birdsong and close to the sound of running water. Indeed, I found this hike so intoxicatingly enjoyable that I almost forgot about the famous castle. Later on, I found that this forest is actually an official nature reserve.

Now, it is possible to reach the castle by shuttle bus. But for anyone contemplating visiting the Eltz Burg, I highly recommend doing so this way. Stepping from under the canopy and into the clearing, and seeing the enormous castle above you, is a tremendous experience—the closest that you can probably get to time travel.

(Another tip for travelers is to bring cash, since the castle does not take credit cards and there are no ATMs in sight. Thankfully, I came prepared. You should also be aware that the castle is only available for visits from April to October.)

At first glance, the castle is both imposing and perplexing. It is difficult to imagine what such a magnificent keep is doing seemingly in the middle of nowhere. This mystery is resolved when we learn that this used to be an important trade route between farmers to the north and the Moselle to the south, where their crops could be shipped downstream. This is such a key point to control that there has been a fortress of some kind here for over a millennium. And for most of that time, the castle was controlled by one family: the Eltz.

This is precisely what makes Burg Eltz so special. It has been in the possession of a single family since the Middle Ages, and it still is today. This has made for truly exceptional preservation. Most of the Rhine castles, for example, were damaged or destroyed in various wars; and what stands today are usually later reconstructions, often with whimsical Romantic fancies added on. Even the best-preserved castle on the Rhine, the Marksburg, does not have its original furnishings. But the Eltz is a kind of enormous time-capsule, an unbroken link to the medieval past.

Burg Eltz has only ever been seriously attacked once. The evidence of this is to be found on a hill overlooking the castle, where the ruins of a small fortress can be seen. This is the Burg Trutzeltz, which was constructed to bombard Burg Eltz with catapults and primitive canons. This was part of a local power struggle of the 14th century, known as the Eltz Feud, in which the knights of Eltz Castle struggled to maintain their independence from the Bishop of Trier. Eventually they capitulated and the family became once again vassals. As it stands now, the castle is remarkable more for its beauty than for its value as a fortification. Indeed, the tall, flat walls of the castle would make it an easy target for canonfire. I would wager that a single piece of artillery could wreck the place.

I climbed up the stairs to the main rampart—quite sweaty by now—and bought a ticket for the next guided tour. It would start in about 45 minutes, which gave me some time to visit the castle’s treasury. This is a kind of miniature museum in what appears to be the castle’s dungeon, exhibiting the family’s most valuable possessions. Some of the objects on display are quite fine, exhibiting the prosperity of this aristocratic family. There are, for example, ceremonial crossbows and ornate hunting rifles. And of course, courtly life requires plenty of fine dining. There are ivory drinking vessels, silverware with mother-of-pearl handles, and even a weird mechanical drinking game, a device which participants would wind up and release on the table, dooming one unlucky (or lucky) couple to draining its contents.

I have to admit that, most of the time, the accoutrements of the upper crust leave me feeling a little cold. As impressive as is the workmanship and artistry required to make such items, to my eyes their aesthetic value is drowned by their proclamation of wealth. This collection, however, was more charming to me for being the accumulated possessions of one single family, displayed in what is still—to an extent, at least—their family home. There certainly is an anthropological value, at least, to seeing authentic examples of luxury in their original context.

Now it was time for the tour. (There are no photos allowed on the tour, but the website has photos of all of the major rooms.)

Once again, I normally find tours of aristocratic or royal dwellings to be kind of depressing. But the interior of Burg Eltz was unlike any other building I have seen. Even though it was obviously the home of a wealthy family, the furnishings of the room often struck me as being charmingly rustic. The roof timbers were visible and the supporting columns were irregularly carved. The Eltz were a family of knights, and their arms and armor form an important part of the decoration.

But by far my favorite aspect of the castle were the wall decorations. These include vegetable motifs vaguely reminiscent of Muslim decorative styles (possibly brought back from the Crusades). Yet compared to, say, the Alhambra’s elegant designs, those in Burg Eltz are sort of clumsy and clodish. I do not mean this as an insult, however, as I found the taste displayed in these decorations to be beguilingly foreign—that is, genuinely medieval, and alien to modern sensibilities of line and color. To repeat myself, a visit to this castle is the closest one can come to a trip back in time, so wonderfully does it preserve the flavor of the Middle Ages.

After an hour, I was back outside. I was both satisfied and exhausted. The only place to eat nearby is in the castle’s café, where I had—what else?—a plate of currywurst and pommes, along with a beer. Fortified, I decided that I ought to explore the lovely forest some more before venturing onward. Thus, I walked on a circular path that goes around the valley below the castle. The best part was the view of the castle from across this valley, its grey spires contrasting against the sea of green around it. By the time I circled back to the castle, I was convinced that this is one of the great destinations of Europe. The castle itself is first-rate. Its dramatic location in the middle of the woods pushes it into another realm entirely.

After another hike, I was back in Moselkern. (In retrospect, I think I could have taken the path instead to the neighboring town of Müden, just for the sake of variety.) Here, I caught a train to the biggest town nearby: Cochem. “Big” is, of course, a relative term here, as Cochem has just about 5,000 residents, making it about half the size of my own little hometown, Sleepy Hollow. Nevertheless, it is a very attractive place, with the local castle—the Reichsburg Cochem—sitting on a hillock overlooking the quiet houses below. This attractive castle, as it happens, is yet another example of Romantic reconstruction, as the original was burned down by French troops in 17th century.

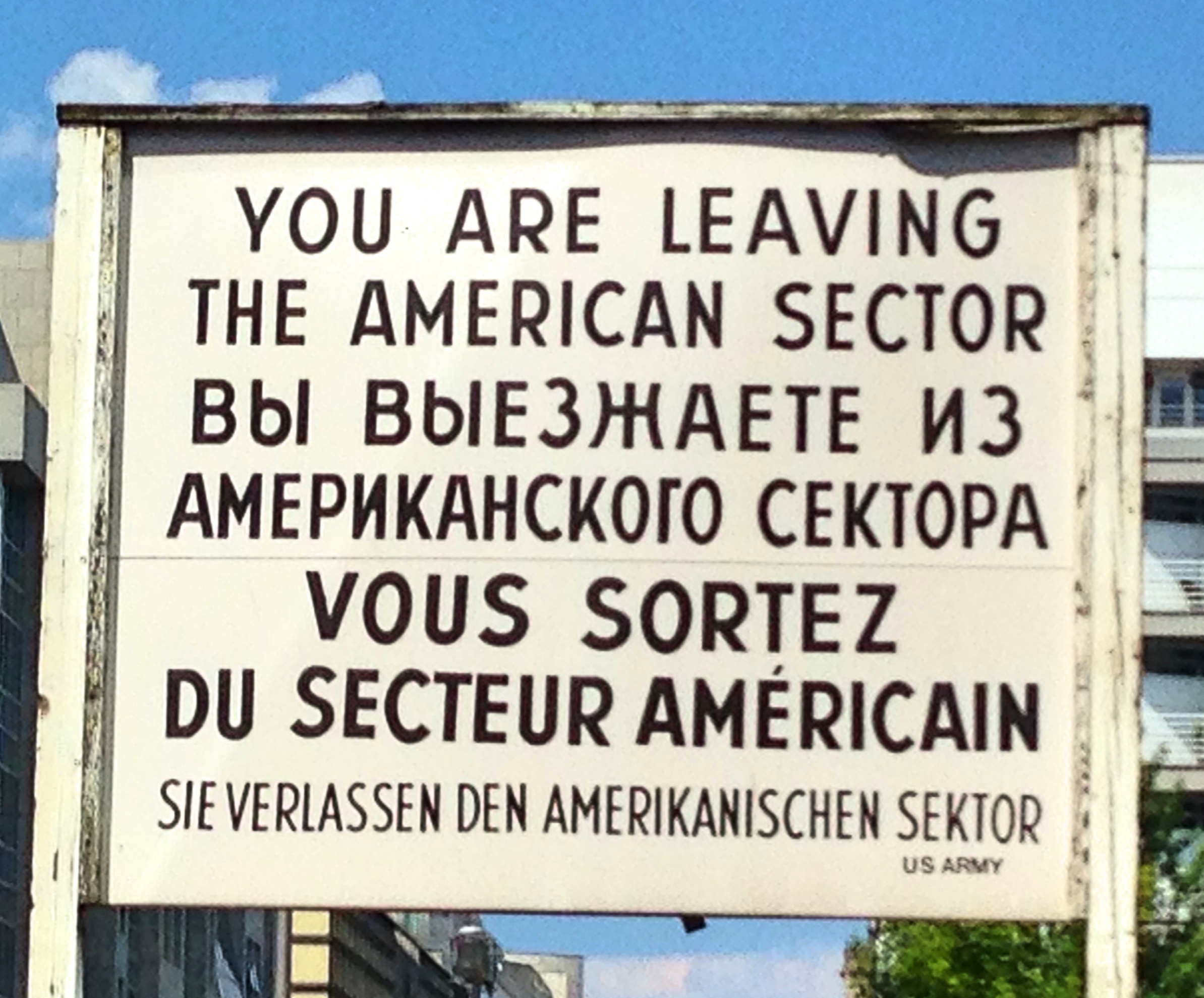

(Cochem has a long history, but perhaps the most interesting thing about the town is that, during the Cold War, it was in this sleepy place that West Germany kept its emergency supply of currency. In a bunker located beneath some nondescript houses, 15 billion German marks were stored away, to be used in case East Germany started counterfeiting their money.)

There is, I am sure, a great deal of sightseeing to be done here. But I was quite saturated by this point in the day, and was far more interested in sampling the local wine. The seemingly endless vineyards surrounding the valley in every direction seemed to confirm this desire. Thus, I found my way to a wine bar on the side opposite the town center, sat down on a wooden chair outside, and had a drink. In fact, I have to admit that I had a few. It was just too pleasant to give it up. The weather was perfect, the wine refreshing, and I had nothing else to do. Also, the knowledgeable bartender was quite willing to explain German wines to a clueless foreigner. I listened intently and retained exactly nothing of what he said.

After I decided that I couldn’t have another glass without jeopardizing my return journey, I reluctantly made my way back to the train to return to Koblenz. I have one night left in Germany.

Koblenz is a proper city, with a population of well over 100,000. Like many places in Germany, Koblenz was bombed nearly out of existence during the Second World War, and had to be rebuilt. As a result, it is not exactly the stereotype of a charming European urban center. Nevertheless, I found it to be quite a pleasant place to relax after my journeys on the Rhine and the Mosel. It was quiet, convenient, and not entirely bereft of charm.

There is only one major tourist attraction in Koblenz, and that is the Deutsches Eck (literally the “German Corner”). This is the point where the mighty Rhine meets the charming Moselle, thus creating a cultural and a literal confluence. It was here that Wilhelm II—last king of Germany—decided to construct one of the many monuments to his grandfather, Wilhelm I. It seems to have been the younger Wilhelm’s object to elevate his grandfather to the status of national hero. He even demanded that Wilhelm I be referred to as “der Große” (“the great”). All over Germany, massive statues of the Kaiser were erected.

To be sure, the first Wilhelm was an important figure in German history, as it was during his reign that, with the help of Bismark, he achieved unification of the separate German states. Much like Italy, you see, for much of European history Germany was split into several dozen states, each with its own laws, currency, and ruler. During the 19th century, both Germany and Italy were unified in a wave of patriotic nationalism, thus allowing them to compete on an equal footing with France and England for domination of Europe. The symbolism of the confluence of these two rivers was surely not lost on those who built this monument.

The enormous equestrian statue that now rides atop the stone pedestal is, however, a reconstruction. The first statue survived the WWII bombing of Koblenz, but was hit by American artillery fire during the invasion of Germany (sorry about that). The pedestal was bare for several decades until the statue was finally replaced after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany. Hoisting up the statue of a dead Kaiser may be an odd gesture to celebrate the end of communist rule, but it did help bring tourists to the city.

When I visited, the place was full of locals and tourists alike. The huge pedestal is a pleasant place to sit and enjoy the river, or for kids to climb and play on. Nearby, one can see the Koblenz cable car, which takes riders over the Rhine (sadly, I didn’t make time to go). The journey ends on the other bank of the Rhine, on the hill upon which sits Ehrenbreitstein Fortress. A real modern fortification rather than a romantic faux-medieval castle, this fortress is not exactly beautiful, but it is perhaps worth visiting for the view alone.

On my first night in Koblenz, I was so tired that I just peeked into a Lidl for a premade sandwich and some chips and ate this paltry dinner in my Airbnb. On my second night, after a day of exploring the Rhine, I made the mistake of choosing a fast food place in the old city center (overpriced and unsatisfying). Finally, on my last night in Koblenz and in Germany, I had the good sense to find a biergarten. There is an excellent one—enormous, with hundreds of outdoor seats—right beside the Deutsches Eck.

Here, I ordered some sausages and potatoes and a large mug of German beer and sat down on one of the wooden chairs under the shady plain trees. Now, there is something that foreigners ought to know when drinking at a biergarten. The lovely glass mugs (or “steins,” as they are called in English, but not in German!) have proven to be so tempting that many people simply walk off with them as souvenirs. To combat this, one must often pay a deposit, called the “Pfand,” which is normally a euro or so. This amount is then returned to you when you bring the mug back to a special window.

Well, there I was, enjoying the fading light of my last evening on the Rhine, sipping an excellent beer and savoring the full feeling in my stomach, when I heard people talking right behind me. It was a couple, and they were wondering how they could use the bathroom. The door, you see, had a lock on it, and you had to put in a euro to open it. However, I had just found out that, if you asked one of the cashiers, they could give you a key to open it without paying. I turned around and conveyed this information in my best German, for which I was heartily thanked.

The interaction then took a strange turn. The female half of the couple spoke quite decent English and started asking me polite questions about myself. I did the same, and found out that they were young newlywed Germans on a little vacation. She then left (to go to the bathroom, naturally) and I was stuck chatting with the male partner. He was quite drunk and for some reason was convinced that he was able to speak English. What came out of his mouth, however, was a totally incoherent series of sounds with the occasional English word thrown in. I tried telling him that I could understand German, but it was of no avail, and I was subjected to a stream of literal nonsense until his partner returned. Hastily, I made my exit, and walked back to the monument.

I sat on the steps and looked out. The Rhine and the Moselle were beautiful in the sunset, and I felt very sad that I had to go. It had been an absolutely wonderful vacation. One day, I am sure, I will come back.