California and New York have a relationship like many siblings. The two have much in common: they are wealthy, cosmopolitan, populous, and mostly liberal. And yet they drive each other crazy with their differences. Whereas New Yorkers are traditionally rude, uptight, stressed, and workaholic, the archetypical Californian is relaxed, gentle, happy, and obsessed with organic food and fair-trade coffee. Who is to say which is better?

I found myself reflecting on these differences as I walked off the plane that had taken me from JFK to the San Francisco airport, in the summer of 2018. The contrast was immediate. Any time you walk into JFK, you soon have someone yelling at you. But the airport here was calm and quiet. All the staff spoke to us in cheerful, polite tones. Of course, I was suspicious.

We were here to celebrate my cousin’s wedding, and to do some sightseeing in our free time. As it happens, all of my mother’s four siblings moved to California when they left home (whether from a hatred of NY or a love of Cali, it is unclear), which means that all of my cousins on my mother’s side were born and raised here in the sunny side of the country. It was inevitable that one of them would get married here.

My aunt picked us up from the airport. We were jet-lagged, tired, and quite hungry, and so we immediately headed to a restaurant. This meant a little bit of driving. Driving is fundamental to the Californian lifestyle; and since so many people live here, that means traffic is as well. But at least there are some nice places to drive. As a case in point, we were soon crossing the Golden Gate Bridge, probably the most famous bridge in our country (the only competition being the Brooklyn Bridge).

Now, when we were crossing this bridge, I am afraid that I mostly did not get a good look at it, since the bridge and its surroundings were shrouded in a thick fog. As I quickly came to appreciate, this is not unusual in San Francisco during the summer. The reasons for such abundant mist are rather elusive to me. Essentially, the fog forms because the air over land is heated more quickly than the air over the oceans. The hot air, then, rises, which means cold air is sucked in to replace it. And this cold air happens to be foggy, since it comes from the ocean. And as this process works best when the sun is hottest, San Francisco summers are foggy.

(The reason I say that this reasoning is elusive to me is that the same logic would seem to apply to any coastal city; but New York, Valencia, and Hong Kong are not foggy to such a degree.)

The climatic consequences of this are interesting. You can have hot sunny days a few miles inland, but in San Francisco itself it will be cool and misty—even a bit chilly. Indeed, Mark Twain famously wrote: “The coldest winter I ever spent was a summer in San Francisco.” That adage has a few problems, however, the first being that Mark Twain never actually wrote it. Another problem is that it is not true to begin with. Winters in New York are a lot colder, as Twain well knew.

Well, if I could see the bridge on that foggy afternoon, I would have seen one of the great engineering marvels of the world. At the time it was built (in the 1930s), the Golden Gate Bridge was the longest and tallest bridge on earth. The bridge connects the city of San Francisco with Marin County (where we were going to eat), spanning the entrance to the ample San Francisco Bay. It owes its fame, not only to its dimensions, but to its elegant design and bold orange color (the paint is called “international orange”), not to mention its dramatic location at the crossroads of land and sea.

Soon enough, we parked the car in the small town of Sausalito. Like the city of San Francisco, this town’s name preserves its Spanish origins (sauce means “willow tree”; sauzal means “a willow grove”; and sauzalito means “a little willow grove”). In the past, the town was a center of ship construction; but nowadays it is a touristy little town full of nice restaurants and cute shops, with a great view of the bay. We ate in an Italian restaurant and I felt greatly relieved. But our chit chat was interrupted when somebody said: “Is that Santana?” Everyone’s eyes turned to look at someone behind me.

“There’s no way that Santana is in this Italian restaurant,” I thought, and mentally justified not turning around. Then I saw somebody walk out of the restaurant: It was, indeed, the legendary guitarist Santana. This was my welcome to California.

San Francisco is located at the tip of a peninsula enclosing the eponymous bay. In many ways the city’s geography was its destiny. A center of commerce with limited land, the city had little choice but to expand upwards. These same factors determined the history of Manhattan; and, as a result, the two are among the most visually striking cities in the United States—a collection of spires rising out of the blue.

If you have gone to Catholic school, you may have guessed that San Francisco was named after St. Francis of Assisi. To this day, the oldest structure in the city is a small white building topped with a crucifix, a part of the Misión San Francisco de Asís, a holdover of the original Spanish mission to the peninsula. One must realize, then, that a city known for being a center of liberal politics, of the Summer of Love, of the gay rights movement, of the ultra-wealthy Silican Valley technicians, was named after a Catholic monk who took a vow of poverty. History is full of these delightful ironies.

We awoke early the next day (though still groggy from the jetlag) to begin our first day of exploring San Francisco. This time, we entered the city through the Bay Bridge, directly across the bay. This of course meant traffic and a toll. But it did provide a rather dramatic entrance to the city. At four and a half miles long (over 7km), the Bay Bridge is one of the longest bridges in the United States. It is not one continuous span, however, but two separate bridges linked to the Yerba Buena island in the middle of the bay. (“Yerba Buena” is a corruption of hierbabuena, which literally means ‘good herb,’ and is commonly used to refer to spearmint.)

This bridge has been reconstructed fairly recently. The original construction consisted of a suspension bridge on the west, and a cantilever bridge on the east. But an earthquake in 1989 damaged the eastern section, which eventually led to its being rebuilt with another, more stylish, suspension bridge, opened in 2013. Photos of the construction look very much like the construction of the new Tappan Zee bridge in Westchester, quite near my home, where another old cantilever bridge was replaced by a sleek and stylish suspension bridge. And, indeed, the same barge crate was used in both constructions: the Left Coast Lifter, an enormous contraption painted patriotic red, white, and blue, used to heave big pieces of bridge into place.

On a clear day, the Bay Bridge would afford you a magnificent view of the city. On this particular day, however, it gave us a rather less magnificent view of gray fog. But this did lend the city an intriguing air of mystery.

Our first stop was Coit Tower. This tower is not exactly conspicuous amid the skyscrapers now crowding the city; but when it was built, in the 1930s, this was the finest view in town. The tower is of fairly modest dimensions, about 200 feet tall. But it stands on Telegraph Hill, one of the hilly city’s tallest and most ideally situated hills. This makes the tower a wonderful place to enjoy the view—when it is not foggy, that is. In any case, the tower is interesting in itself. Made of unadorned concrete, it has a vaguely industrial shape, perhaps like a sprinkler. Considering that the tower is dedicated to fallen firefighters, many have surmised that it was to look like a fire hydrant. The resemblance is apparently coincidental, however.

Coit Tower owes its name to Lillie Hitchcock Coit, a wealthy dowager who patronized the volunteer fire department, and who left money in her will for the beautification of the city. I would say that the money was well spent, considering the tourists crowded into every inch of the building. We entered, paid the fee, and went up to the top. The building is narrow and there is only one small elevator providing service up and down. In any case, as soon as I reached the roof, I wanted to turn back. It was rainy, the wind was howling, and the fog put a damper on the view.

But Coit Tower has much to offer besides its view. On the bottom floor, there is a continuous mural running across the outer and inner walls of the hallway. It is detailed and impressive work, done during the height of the Great Depression, under the auspices of the Public Works of Art Project. Indeed, Coit Tower was the pilot project of this organization, an experiment in using public funds to employ artists to beautify public buildings. The results are still heartening. The murals are done in a Social Realist style, showing stylized scenes of America.

What makes the art “social realist” is not so much that the paintings are particularly realistic, but that they attempt to encapsulate the everyday American experience. Thus, we see street life, factories, and farms, rather than saints, heroes, or Greek gods. Personally I found the murals both aesthetically pleasing and even vaguely inspiring—showing pride and faith in our sprawling country. Certainly, such a thing seems very distant nowadays. Perhaps we ought to bring back the Public Works of Art Project. I am sure there are still lots of needy artists willing to paint inspirational scenes in public spaces.

After this we headed to the Financial District. Anywhere money is centered, big grey buildings are likely to follow; and so this is where the city’s skyscrapers are found. When you factor in the regular grid pattern of the streets, the final result looks remarkably similar to midtown Manhattan (though not as dirty). The Financial District even has its own Wall Street, in the form of Montgomery Street, one of the country’s great concentrations of capitalist activity.

For over forty years—from 1971 to 2017—the skyline of San Francisco was dominated by the Transamerica Pyramid, a daring modernist triangle of glass and steel. Even now, the building seems futuristic in its design. The same cannot quite be said for its younger brother, the Salesforce Tower, which surpassed the pyramid upon its completion in 2017. It is difficult to find anything positive to say about this building’s design. Its shape calls to mind objects not normally mentioned in polite conversation, and its bloated form does not harmoniously blend in with the San Francisco skyline, but dominates and disrupts the picture. I must admit, however, that the building is an impressive technical achievement, since erecting safe skyscrapers in the seismically-active city is no easy feat.

For lunch, we headed to Yank Sing, a dim sum restaurant in the famous Rincon Center. The building itself has an elegant art-deco design. But it is most notable for the murals inside, which also date from the Federal Arts Project. The best murals are to be found in the old post office, and were painted by the Russian immigrant Anton Refregier. They are also part of the social realist tradition, and treat of the history of San Francisco—covering major events, like the 1848 gold rush, the 1860 completion of the trans-continental railroad, and the horrible 1906 earthquake. Refregier’s sense of injustice and oppression caused some controversy, as it led him to portray some of the less attractive scenes of American history—a choice that got him into trouble as a communist sympathizer during the Red Scare. Thankfully, the murals have escaped destruction by bigots.

After we finished eating and enjoying the art, we got back in the car to head to the most iconic stretch of asphalt in the entire city: Lombard Street. This is a twisting street, consisting of eight hair-pin turns, that leads down one of San Francisco’s many hills. I have never seen anything else like it. The last time I had visited San Francisco was over ten years earlier, when I was quite young, and I still had a vivid memory of this road—so crazily misshaped. On this particular summer day, as the fog began to clear, the street was quite beautiful. Flowers bloomed in the little gardens beside the pavement, and plants even colonized one colorful house nearby.

This seems like an appropriate time to discuss San Francisco’s topography. Like Rome itself, San Francisco claims to have been built on “seven hills,” though there are an awful lot more than seven hills in the city. Indeed, there are six times more: 42 hills, ranging in height from 200 to over 900 feet tall. I can only imagine that the city’s marathon is punishing on one’s knees, and that owning a car means frequent brake repair. It is probably due to this inclination that San Francisco developed its famous cable car system—one of the city’s most identifiable symbols. In its hilliness and its in street cars, this Californian city has an intriguing resemblance to Lisbon, a city with its own big orange bridge.

Now we decided to visit the city’s most famous book store: City Lights. I must confess that I had never heard of it, and I walked out thinking that it was just a particularly nice shop. But my dear mother soon informed me that it was this humble store which published Allan Ginsberg’s iconic collection, Howl and Other Poems, in 1956—a pivotal moment in the Beats movement, as the resulting obscenity trial changed censorship practices and catapulted Ginsberg to national fame. When I found this out, I went right back inside and bought myself a copy of this poem. (Fortunately, after the store’s continued existence was threatened by the coronavirus lockdowns, an online fundraiser helped to save the business.)

After this adventure in literature, we retreated to the nearby Caffe Trieste for some caffeine. This is an elegant little establishment which holds the distinction of being the first Italian-style café on the West coast. As you might expect, having a quality coffee house near a center of the Beats movement meant that this spot also became a meeting-point for literati, like Alan Watts, Jack Keruac, and Alan Ginsberg himself. But I was mostly struck by the prices. Coffee in San Francisco is not cheap! Indeed, ever since we landed, everything I saw seemed absurdly expensive to me; and this is no coincidence.

Though San Francisco was the center of the Beats movement, the setting of the 1967 Summer of Love, and in the 1980s the epicenter of gay liberations, nowadays the city has gone the way of so many major cities—it is simply too expensive for anyone but high-earners to live there. A big part of this is due to the proximity of Silicon Valley, just a few miles south. The influx of big business has made the cost of living shoot up: the typical rent is higher than $4,500, and the typical house costs well over one million. According to this article, homelessness has increased by 17% in the last two years alone (and who knows how the coronavirus depression will affect that!). In short, it is not a great city to visit if you wish to travel on a budget.

Hippiedom and corporations aside, there are some traces of religion left in the coastal city. I have already mentioned the old San Francisco mission. There are some impressive church buildings as well, such as Grace Cathedral. This is the city’s Episcopal cathedral. The structure was completed in a resplendent neo-gothic style, doing a convincing imitation of Paris’s Notre-Dame. Yet the church doors are not gothic, but Renaissance in style; indeed, they are full-scale replicas of the Gates of Paradise. These are a set of bronze doors by Lorenzo Ghiberti, made for the baptistry of Florence, now considered to be great masterpieces of the early Renaissance. The replicas in San Francisco are wonderfully done, and were just as enjoyable to examine. The interior of the cathedral is quite as majestically gothic as the outside, with gilded paintings and stained glass illuminating the stone space. It even has a replica of Chartres’s labyrinth.

Not far off is the city’s catholic cathedral, Saint Mary’s. Completed in 1971, the building is so oddly shaped that you could be forgiven for not thinking it was a place of worship. To me, it resembles an enormous washing machine agitator, ready to rinse off the sky. While I am not an enemy of modern architecture, I do think that churches ought to be a bit more solemn and less, well, ridiculous in appearance. This church was built to replace the original cathedral, which had been standing since 1854. Reduced to the status of a humble church, this building still stands, now called Old St. Mary’s. While no architectural marvel, the simple brick building does have the conspicuous advantage of looking like a church.

Perhaps the most beautiful catholic church in the city is Saint Peter’s and Saint Paul’s. It is a pale white building with two long, narrow spires. The interior is quite lovely, with a coffered ceiling leading to a semi-dome above the main altar. The church even has a full-scale replica of Michelangelo’s Pietá—and it is extremely well-done. A center of the Italian-American community, the church holds services in Italian as well as in English. Somewhat more surprisingly, the church also holds services in Cantonese!

After some milling about in town, we got back in the car for the day’s final destination: Lands End. As you might have guessed, this is one of the many spots in San Francisco where earth meets water. More specifically, this is a park near the mouth of the bay. It is quite a romantic spot, with shrubby trees clinging to rocky soil, with the wind and the waves crashing in. The visitor’s center sits above a kind of rocky crater, beside which stand some ruins of old structures. This is all that remains of the famed Sutro Baths, an enormous complex of swimming pools that used to attract thousands of visitors.

I took some time to walk along the shoreline. The landscape is beautiful and dramatic, with whitecaps washing over sunbleached rocks, and the rolling hills crawling out from under the screen of fog. As I walked on, the Golden Gate Bridge came into view—still partially shrouded by the mist, but magnificent nonetheless.

I also noticed something strange in the water, a sort of concrete stump in the middle of the bay. I learned from a nearby sign that this is the Miles Rock Lighthouse. It was built after the SS City of Rio de Janeiro ran into a submerged reef and sank in 1901, killing 135 of the 220 on board. Originally, this lighthouse—which is built on a lonely rock—had the recognizable form of a tower, but in the 1960s the top floor was demolished in order to make room for a helicopter landing pad. Nowadays, the lights are automated, so nobody has to sit there, alone, in the middle of the foggy bay.

So ended my first day in San Francisco. We got back into the car and drove by the famous Cliff House restaurant, which overlooks the Seal Rocks (both of these very accurately named). Then, after a pizza dinner, we were on our way back to the suburbs. But I would return.

San Francisco is blessed to have the rail system with the dorkiest name in the country: BART, which stands for Bay Area Rapid Transit. For my next day in the city, I hopped on the BART by my aunt’s house in the suburbs, and disembarked at the Embarcadero. This is the city’s waterfront to the east, facing the bay; and its name is yet another mark of the city’s Spanish heritage (embarcadero is a place where you board a vehicle). With the weather quite clear and sunny, I could see the full span of the Bay Bridge. Infrastructure is inspiring.

I walked along the water, enjoying the gentle breeze and the bright sun, pausing occasionally to examine anything that caught my eye. This certainly included the giant sculpture, Cupid’s Span, which consists of a huge bow and arrow that have been stuck into the ground. Designed by the artist team Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen (who are married), the sculpture is meant to pay homage to San Francisco’s history as a city of love. (But to me it looks as though cupid had carelessly lost his weapon, which is not good news for would-be lovers.)

Next I passed the Ferry Building, which looks vaguely like a medieval city hall—with a large clocktower shooting up from a lower structure. This beaux-arts style building actually took its inspiration from the Giralda, the half-Moorish, half-Renaissance bell tower of Seville’s cathedral. As you may imagine, before the construction of the major bridges, ferries were quite important to the life of the city. But as time went on, the building came to be seen more and more as a historical monument, and parts were even rented out for use as office space. Nowadays, however, the building has regained some of its former luster, and is a tourist attraction in its own right—with a food court and a market in the “Grand Nave.” It is still the main ferry hub for the city.

While I walked along, I noticed an interesting presence on the streets: big, hulking streetcars. This is the city’s historic streetcar service. Much like the city’s cable cars, these streetcars now mainly serve a nostalgic purpose, ferrying tourists in creaky wooden and metallic boxes across the city. But they really are quite charming to see, as they scuttle past like big colorful beetles. Incidentally, I also passed by the Fog City Diner, a landmark restaurant with a classic, retro appeal. I later ate here with my family, and the food was fantastic.

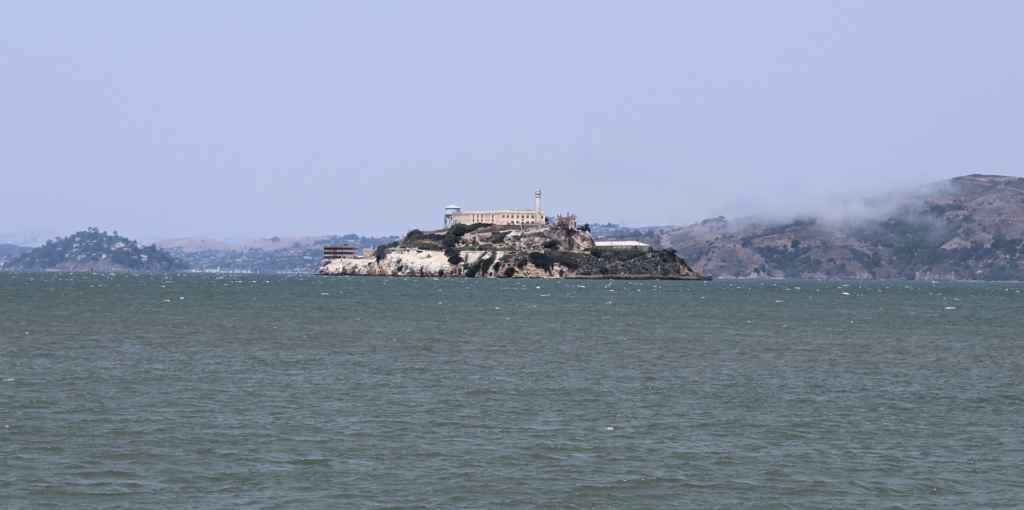

My next stop was Pier 39. This pier is one of the city’s major tourist centers, which means it is crowded and filled with all sorts of touristy junk. But the pier is still worth visiting, if only for the view. From the end of the dock, you can see both the Golden Gate and the Bay Bridge; and behind you there is Coit Tower and the Transamerica Pyramid. What most attracts attention, however, are the Sea Lions. A few decades ago, these animals preferred to lounge on the rocks near Cliff House, but for some reason they moved inside the bay and set up camp here. The sea lions took over these docks and have not budged since. The number of animals present on any given day fluctuated. When I visited, there were probably around 50; but there can be many times that number.

There are still more things to see from the pier. The SS Jeremiah O’Brien was docked not far off in the bay, a so-called Liberty ship. These were medium-sized cargo ships mass-produced during the Second World War, to ferry goods and men across the Atlantic. This particular ship has quite an impressive record, having been part of the D-Day Armada and seeing use in the Pacific Theater. The ship normally sits in the dock, available for tours; but occasionally it takes tourists on short rides.

Yet by far the most famous thing in the bay is not a ship, but an island: Alcatraz. You may be surprised to learn that this name also dates back to the Spanish occupation. Nowadays, the word alcatraz is used to refer to garrets; but at the time the word was used for pelicans (both are white, coastal birds). Thus, Alcatraz is the island of the pelicans—as it remains, incidentally.

(It is also curious to note that this word—like virtually all the Spanish words that begin with “al-”—is a loan word from Arabic, dating all the way back to Moorish Spain. It most likely comes from al-ḡaṭṭās (in Arabic: الْغَطَّاس), which means “the diver.” So the name of one of the world’s most famous prisons comes from a Spaniard misidentifying a bird, using a word that was misheard from Arabic several centuries earlier. History is a funny thing.)

The last time I had been in San Francisco, I visited this island with my family. Nowadays, unfortunately, you need to have booked tickets in advance in order to visit, so we missed our shot. But I do have a strangely vivid memory of my time on this island. It is an arresting mixture of the wretched and the beautiful—with dark, concrete cells surrounded by ocean and sky. Because of the frigid waters and strong tides of the bay, the prison was considered escape-proof, though three prisoners tested this notion in 1962 (as dramatized in the classic film). The iconic gangster Al Capone was imprisoned here, as well as the famous “Bird Man” of Alcatraz, Robert Franklin Stroud, who did important work on bird diseases during his many years of imprisonment. (Alcatraz, however, did not let him have either birds or equipment.)

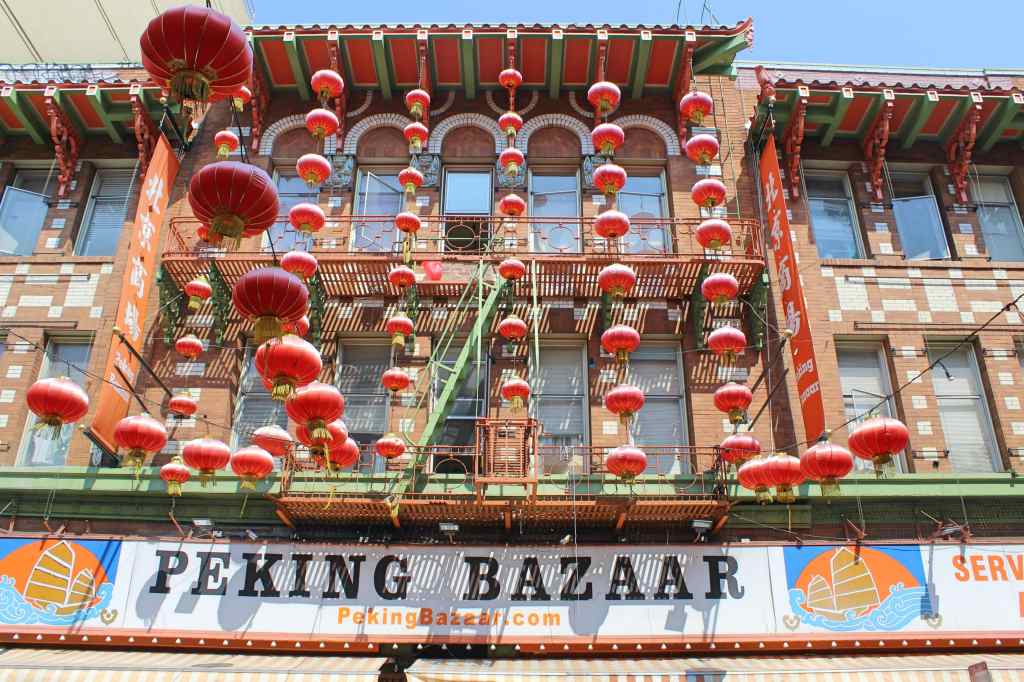

By now, I had had enough of the overpriced and gaudy seaside, so I headed to one of San Francisco’s great neighborhoods: Chinatown. San Francisco has a claim to being the most important city in Chinese-American history, as the city’s Chinatown—established in 1848—is the country’s oldest. Though New York City has a higher Chinese population in total, people of Chinese descent make up a greater portion (about a quarter) of San Francisco than NYC or anywhere else in America. As it happens, most of the residents in the Bay Area hail from southern China, where Cantonese rather than Mandarin is spoken (which explains why some services at St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s are offered in that language).

The most recognizable landmark in the neighborhood is the Dragon Gate—a stylized arch (called a pailou), with two fearsome guardian lions on either side. This was actually a gift from Taiwan, and was erected as a kind of PR stunt during the Korean War for the Chinese-American community (since the People’s Republic of China was fighting on North Korea’s side).

Two other notable landmarks are the Sing Fat and Sing Chong buildings, both on Grant Street. These feature an arresting combination of typical Western and Chinese building styles—looking like ordinary buildings that have grown ornamental frills, towers, and swoops. But elaborate architecture is not needed to know that you are in Chinatown. Every surface is covered with Chinese characters, and red lamps hang over the streets.

I had quite a bit of fun simply walking around. I love walking into Chinese grocery stores and food shops, as they are always full of unfamiliar products and brands, all of them wrapped in sparkling colors. As I walked by an alley, I spotted a couple men practicing a dragon dance. And I even paid a short visit to the Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Company, which is exactly what it sounds like: a small factory for fortune cookies. But the best part of visiting Chinatown was the food. I waited online at a dumpling shop and walked out with enough food for three people, all for less than $10. In San Francisco, where a ham sandwich can cost more than that, this is beyond a bargain. And it was delicious.

Next, I wanted to visit a museum. San Francisco has plenty to offer in that regard. There is the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), which has a vast collection of 20th century art, all housed in an appropriately daring building. There is the Legion of Honor, an imposing neoclassical building with a wide-ranging collection of (mostly European) art; and the de Young Museum, which mainly focuses on art from the United States. If you are looking for something a little more interactive, the Exploratorium—located on the Embarcadero—is full of participatory exhibits. (The museum was the brainchild of Frank Oppenheimer—a far more beneficent gift to humankind than Frank’s older brother’s gift of the atomic bomb.)

But I only had time for one museum, and the one which interested me the most was the Asian Art Museum. This museum is located right across from San Francisco’s city hall—a lovely Palladian structure with a gilded dome—as well as from the main branch of the San Francisco public library. The museum is an enormous institution in its own right, with one of the country’s great collections of Asian art. As I walked through the galleries—going from India, to China, to Japan—I found myself more and more deeply amazed, both at the quality of the collection and of the art itself, and once again filled with a burning desire to learn more about these cultures. But as I am, alas, still quite deplorably ignorant, I will let my photos do the talking:

This concluded my last full day in San Francisco. It was late and I needed to get back to my Aunt’s house for dinner. So I made my way to the nearest BART station and was whisked back across the bay. But I still had time for a last glimpse of the city.

On one beautifully unfoggy day, I took BART into the city center. I was going to go on a bike ride with my cousins. And to get to our rendezvous-point, I had to walk through one of the most famous neighborhoods in San Francisco: Haight-Ashbury.

Of all the famous cultural moments in the history of San Francisco, the 1967 Summer of Love may be the most iconic. That summer, tens of thousands of hippies—dressed in tie-dye and bell-bottom jeans, taking every type of substance you can imagine—converged on the city in order to protest war, reject capitalism, and in general to imagine a different kind of world. It was one of the high points of the sixties counter-cultural movement, an event that helped to identify an entire generation. The moment was so notable as to even merit its own hit song: “San Francisco,” by Scott McKenzie. It summed up the moment thusly:

All across the nation

Such a strange vibration

People in motion

There’s a whole generation

With a new explanation

And indeed there was.

All hippiedom aside, the neighborhood is quite beautiful in itself, for its array of classic Victorian-style houses. These constitute perhaps the most distinctive buildings in the city—stately, elegant structures of wood and many windows, all scrunched up against one another in the city’s rolling hills. Residents have taken to painting them mellow, contrasting colors, leading to the popular nickname “Painted Ladies.” Personally, I found the neighborhoods quite charming. And I was also taken with the detectable aftershocks of the summer of love in the neighborhood, such as an “anarcho-syndicalist” bookstore (presumably one doesn’t have to pay?), and the coffee shop where I waited, which served a very nice brew in a space dominated by used books.

Finally it was time to assemble with my cousins. Within mere minutes, we had rented bikes and were pedalling our way through Golden Gate Park. If San Francisco’s Painted Ladies are the city’s equivalent to New York City’s brownstones, then the Golden Gate Park is the city’s Central Park. In fact, it is quite a bit larger than Manhattan’s greenspace, which is impressive in a city that is a fraction of NYC’s size. However, the two famous parks could never be confused by a visitor. Whereas Central Park is full of maples and oaks over a gently rolling field of grass, the Golden Gate Park has palm trees, eucalyptus, and cypress, which to me seemed quite beautiful and exotic.

Even more exotic were the bison, which were lounging casually in a field. This was almost certainly the first time I had ever laid eyes on a live bison. (There are stuffed ones in the American Museum of Natural History.) And, of all places, I did not expect it to happen in San Francisco. The park had purchased a herd back in 1899, when the country’s bison population was threatened; and it seems the habit of keeping bison is hard to kick.

We made our way through the patchwork of roads, paths, and bridges, until we came to a large open garden. This is where the de Young Museum (mentioned above) is located, as well as the California Academy of Sciences. But I was more interested in a lovely sculpture of two of my heroes, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, praying to their creator Cervantes—yet another echo of Spain in this Californian city. We dismounted and walked for a bit, enjoying the sun and the bird calls (most of which were entirely unfamiliar to me), until we came to the park’s end.

Suddenly, the sky opened up and the land expanded into a sandy beach: the very literally-named Ocean Beach. There were a few scattered surfers in the distance (which caused my cousin’s boyfriend, an Australian, keen envy). Behind me, I observed a beautiful Dutch-style windmill, which had been constructed in 1903 as a tasteful way of pumping water into the park.

My time in the city was quickly coming to an end. We pedalled back to the other side of the parks, returned the bikes, and then had dinner in a bar. Soon, I was on the BART, heading back to the suburbs.

Inevitably, I missed a great deal during my trip. I would have liked to have visited more museums and to have seen Alcatraz once again. I also regret not paying a visit to the Castro District, one of the country’s most important gay neighborhoods. It was here that Harvey Milk became the nation’s first openly gay elected official, before his gruesome assassination. It was also here that the nation first came to grips with the horrible AIDS epidemic of the 1980s.

San Francisco is, without a doubt, one of the great American cities. Its history is fascinating, and its personality is unmistakable. Yet the city I had seen was very different from the city of Allen Ginsberg, Scott McKenzie, and Harvey Milk. Nowadays, San Francisco is the city of Mark Zuckerberg, Steve Jobs, and Elon Musk. Whether or not this is an improvement, I will let its residents decide.

Soon enough I was walking through the airport gate, back into JFK. And it was not long before someone was yelling rudely. It felt good to be home.