The city of Madrid is divided into 21 “districts,” which are further divided into 131 neighborhoods. Pacífico belongs to the Retiro district, so named for the iconic park which it encompasses. This neighborhood—along with its sister barrio, Adelfas—composes the southernmost part of this district, where some 50,000 reside. And for the last seven years, I have been one of them.

Pacífico is central without being in the center. Extremely well-connected by public transport—the Méndez Álvaro bus station is to the south, Atocha station to the west, the bus hub of Conde de Casal to the north, and two of the most important metro lines running through it—Pacífico is nevertheless quiet and residential, with no tourism to speak of.

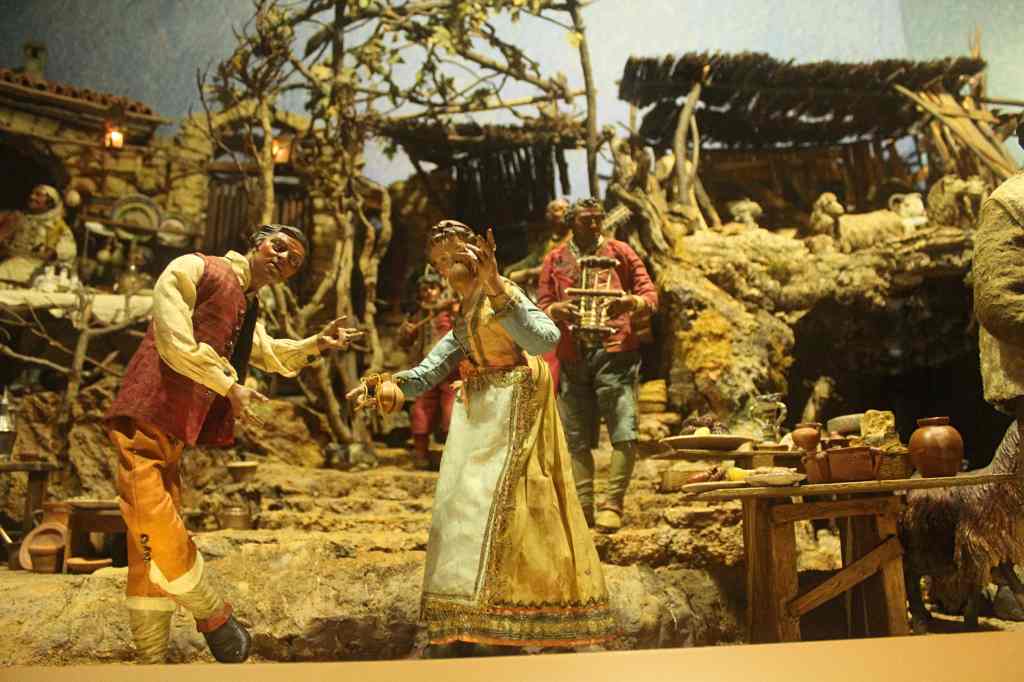

I have had occasion to write about my neighborhood before. The beautiful (but obscure) Pantheon of Illustrious Men is located here, along with the Basílica of Atocha, where traditionally the royal family are baptized. Nearby is the Real Fabrica de Tápices, another fascinating place that most visitors overlook. This was built as a “royal factory” in the 18th century to make luxurious tapestries and carpets for the palaces; and it maintains this function to this day, though it is now privately owned. If you reserve in advance, you can visit the factory and see the workers painstakingly assembling enormous and intricate tapestries by hand, thread by thread.

As it is close to Atocha, the neighborhood is also rich in transport history. At the extreme western edge of Pacífico is the Museo La Neomudéjar, a modern art museum with rotating exhibits in a former train workshop. It is still full of decaying industrial ambience and abandoned equipment. Closer to where I live, you can visit the Nave de Motores, where the massive original power generators of the Madrid Metro are stored.

The administrative heart of the neighborhood, where the government offices are located, has a curious history. The building complex was first constructed as warehouses to store goods imported from abroad, for which it was known as “Los Docks” (yes, in English). This business soon failed, and it was turned into a military barracks, a function it maintained until 1981. After its acquisition by the municipal government, however, several historical buildings were demolished to make room for modern offices—a move widely criticized. The surviving original buildings have since been turned into a huge public sports center, with a gym, football and basketball courts, and a gigantic pool.

This sounds quite sunny and uplifting. Yet this sports center—named Daoíz y Velarde, after the Spaniards who instigated the uprising against Napoleon’s invading troops—has been touched by tragedy. For it was very near here, in 2004, where one of the bombs went off in the infamous March 11th terrorist attack (the train tracks run right by the buildings), and the sports center had to be used as a field hospital for the victims. 250 victims were treated there, of whom 10 lost their lives. A commemorative plaque marks the event.

More recently, the Daoíz y Velarde Center has acquired an important music venue: the Real Teatro de Retiro. This is an offshoot of Spain’s royal opera house, where shows are tailored for a younger audience, with the aim of involving a new generation in classical music.

As interesting as all this history may be, it is not the reason I like to live here. Apart from being (for the moment) reasonably affordable and quite well connected by public transport, Pacífico is attractive for the wide variety of small businesses. Indeed, as an American, I am constantly surprised at the number of small, family-owned shops in Madrid. If you want to buy groceries, shoes, sports equipment, or whatever else in the United States, chances are you will find yourself at a strip mall, shopping at one of a small number of chains. Not so here.

My impression over all these years—though, I admit, it is little more than a vague one—is that the business landscape in Spanish cities resembles how American cities were ten or twenty years ago, before gentrification and consolidation took a toll on small business. However, I certainly do not know enough about the economy to argue the point.

Regardless, I think that these sorts of small, family-run neighborhood shops are a precious resource in any city, something worth preserving in the face of economic pressure. Thus, I set out to learn more about some of my favorite local businesses.

My first stop was my local ferretería (a hardware store and not, what some English speakers might think, a store specializing in ferrets). The Ferretería Pacífico has been around since 1995, and—judging by the constant flow of customers that made it difficult to ask questions—it is still going strong. I am a frequent customer myself, as the store sells everything from frying pans to drying racks to power tools. But my favorite service they offer is to sharpen knives.

The staff at the store are knowledgeable and friendly. And when I asked their secret to staying in business, they offered me an explanation that, though cliché, seems quite true: they offer customers personal attention. I have experience of this. When I was ineptly trying to install a curtain in my apartment, they talked me through the process and sold me everything I needed. When I asked what struggles they have remaining afloat as a business, I was given just one word in reply: “taxes.”

Somewhat further up the hill that leads to Retiro Park is my barber, Almudena. She works in the Pelúqueria Félix, a tiny barber shop on a quiet street. The shop is named after her father, who opened the business in 1976. Almudena learned her craft from him. She gives excellent haircuts, mostly eschewing the buzzer and working with a comb and scissors. When I asked about challenges, she also complained about taxes. The IVA (value-added tax) is 21%, meaning that a fifth of what is paid to her is for the government.

In addition, as somebody who is self-employed, Almudena must pay the “autónomo” tariff. This is a flat-rate fee that people who own their own businesses must pay in order to be legitimate. Strangely, this fee is relatively standard, varying only slightly depending on your income. Certainly I am in no position to judge the Spanish tax code, but as a general rule flat taxes are usually harder on the less fortunate.

The heart of the neighborhood, as far as shopping is concerned, is the traditional market—the Mercado de Pacífico. There are mercados del barrio all over the city, and they all have the same basic design: small stands selling high-quality products, often on a subterranean level. (I believe the reason that markets are often relegated to basements is to minimize the smell; fishmongers and pickled products are often present.)

There, while doing some shopping, I spoke with Francisco. He runs a fruit stand in the market, and has been at it for a long time. That’s an understatement: he is 70 now and started working in the market at the age of 13. I was delighted to notice that his scale was not in euros (adopted in 1999), but pesetas! When I offered to email Francisco this article, he showed me his old flip phone and told me that he didn’t use the internet. What a blissful existence!

Down the street is the oldest shop I was able to find, Zapatos San Román. It was opened in 1959 (as a certificate hung on the wall proudly states) by the father of the current owner, José. He has been working in the shop for 40 years, and still mans the cash register. The store is characterized by its giant “escaparate,” or old-fashioned display window. This is not limited, as in most stores, to a small cabinet out front; rather, the escaparate occupies fully half the store, wrapping around the visitor, creating a miniature landscape of shoes.

Down the street is another store devoted to footwear: Reparación de Calzado Alfaro. To be honest, I didn’t know that there were still professional cobblers in the world. The word itself, in English, calls to mind Victorian novels. But Rafael has been there for his whole professional life, following in his father’s footsteps, who opened the store in 1985. And he is doing very good business. When I visited him, so many customers came in that I had to retreat and return at a less busy time. But he does not only serve the locals, and not only the city of Madrid. Indeed, his business is not even limited to Spain. While there, he showed me an order that he had gotten from Belgium!

When I asked why he was doing so well, he said that his was a disappearing profession; and so anyone who needs a shoe fixed must search far and wide for a good cobbler. That search will, apparently, only get harder. Though Rafael inherited his business from his father, who himself learned from his own father, there will be no fourth generation of his shoe repair business. “It ends with me.” In response to my (perhaps silly) question of why people bother to get their shoes repaired, he told me a Spanish saying:“Te quiero más que a mis zapatos viejos.” That is, I love you more than my old shoes. And a pair of well-worn shoes are, indeed, something to cherish.

A bit up the block from my former apartment, on Calle de Cavanilles, there is a shop that holds a special place in my heart. It is Deportes Periso, a small sporting goods store. And it is special to me because, shortly before the Coronavirus Lockdown, I bought a pair of gray sweatpants there that got me through the isolation. Considering its size, the store has a lot of merchandise on offer—tennis rackets, sports jerseys, and lots of running shoes.

It was opened in 1978 by the current owner, Ana, and her father. As it happened, while I was there interviewing for this article, her father walked in. He’s in his 90s now and very personable. He told me about how the neighborhood had changed. Physically, he said, it has remained quite the same as it was decades ago.* But the demographics have changed. Since the 1980s, the neighborhood has gone from being mostly young to predominantly old. And of course there are more immigrants.

(*This isn’t exactly true. The big and unsightly Pedro Bosch bridge, which connects Pacífico with Méndez Álvaro, over the train tracks, was recently shortened and pedestrianized. And in general the neighborhood has become more bike friendly, with special bike lanes installed on Calle Doctor Esquerdo. However, there is still much progress to be made in that department, as evidenced by the death, just last month, of a bike delivery rider around the corner from my apartment. He was hit by a taxi in the early morning.)

But there are signs of encroaching gentrification. Across the street from Deportes Periso, for example, is an artisanal olive oil store; and considering how much the price of even store-brand olive oil has risen in the past year (well over 100%), one can imagine that people must have expendable income if they’re buying the fancy stuff.

Perhaps the most interesting small business I came across was that of Javier Pascual. He owns a merry-go-round that is parked in a small lot on the Avenida del Mediterráneo. He has been at it a long time, having established himself in the neighborhood in 1981. He comes from a family of carnival ride owners. Indeed, in the past, he owned more rides, but now operates just his “tiovivo” (as the Spanish call it, for some reason).

I have to admit that I was surprised that he could stay in business with a single carousel. Certainly it is hard for me to imagine anyone in my country making a living out of a merry-go-round. But again my expectations were disproven, as so many children came during my visit that I had to call off the interview and return later. (I didn’t have a ride myself, but it looked fun.) Javier works very hard. He’s open seven days a week, even Sundays. In the slow season, when Madrid empties out during the unbearable summer months, he backs up and goes to the fair in Cuenca. Then, he has his contraption repaired in August, ready to get back to work in September.

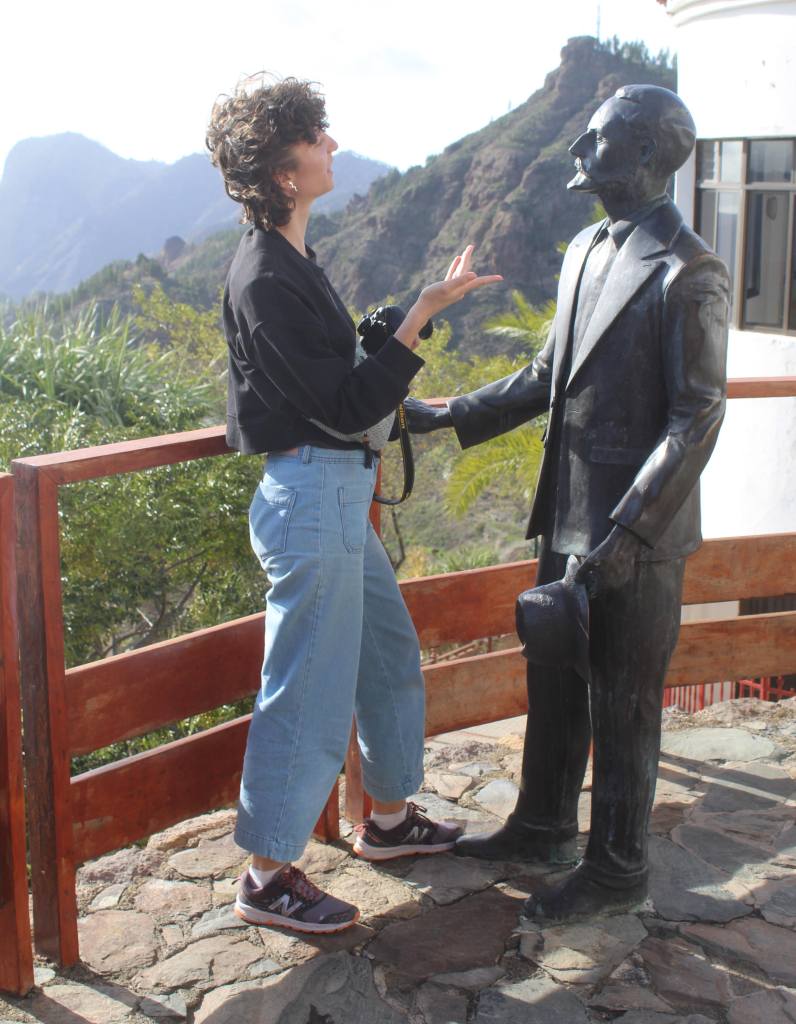

To round out this piece, I thought it right that I interview some of the more recent arrivals to my neighborhood. So I went to Union Frutas, a fruit stand near my house owned by a Chinese immigrant couple. I am a frequent customer, as the shop has very long hours (especially on Sunday, when so many stores close) and has extremely affordable prices. It has been open for 12 years. The husband, Diego (he goes by a Spanish name), moved to Madrid in 2003 as a young man, following in the footsteps of his father, who lived in the Canary Islands. His wife, Li Fang, followed a few years later. When I asked Diego about the differences between work in Spain and his homeland, he replied that he had never had a job in China, so he couldn’t compare the experiences.

All of these stores have survived so long, in the face of competition from chains, by forging connections with the locals—something I witnessed in every shop I visited. It is small shops like these that give a neighborhood its flavor and personality, and which make Pacífico a wonderful place to live. And this is not even to mention the bars!