Four years ago, I ran my first race, the Madrid Half-Marathon. Since that time, running has become a regular part of my life. I signed up for the same half-marathon in 2020 (postponed to 2021 because of the pandemic), and then in 2022, finally getting my marathon time down to 1:55. I also completed several 5ks and 10ks, and even a grueling trail run in El Escorial, which covered 20km of distance with 1,000 meters of elevation difference thrown in (we had to go up and down a mountain). As you can see, I got a little obsessed with running and racing.

But like many runners, I felt incomplete. I had not done the most iconic of all races: the Marathon. Now, of course, this was an illogical thought. There is nothing magical about 42.195 kilometers. And there are many excellent reasons to avoid such a long distance and to stick to other, more reasonable races. Indeed, as you will see, I am not even convinced that training to run such a long distance is even particularly healthy. But logical or not, reasonable or not, I wanted to overcome the challenge, and so I committed myself to the 2023 Madrid Marathon as a kind of Christmas “present” to myself.

There are tons of resources and training plans available to anyone preparing for a marathon. I followed one in a book by Matthew Fitzgerald, but I am sure that most of them contain the same basic scheme: a period of augmenting distance, two weeks of “peak” training, and a tapering-off period of two to three weeks before the race. This is essentially what I did. On the weekdays I would run two or three times, either an hour-long easy run or some sort of speed training. Then, every Saturday, I completed a long run of ever-increasing distance—starting at a half-marathon distance, and capping out at 19 miles (30 kilometers). Most of the training resources I consulted advised against going farther than this distance, or training for more than three and a half hours, since this is too stressful for the body to recover from.

As an aside, I also noted with curiosity that there are several different schools of thought when it comes to training. A serious runner I know, for example, advised me to focus my effort on interval training (running relatively short distances at high speed, then walking to recover, and repeating). The sports writer Matthew Fitzgerald, on the other hand, recommends mainly long runs at a very low intensity, with just a bit of speed training thrown in. Other runners swear by strength training and footwork exercises. Many other runners have no method at all, and just go as far and as fast as their feet can take them with every run. I suppose these differences probably don’t matter much in the end, so long as you are putting your body under the appropriate stress (and thus provoking an improvement).

For what it’s worth, I basically followed the Fitzgerald advice, and stuck to lots of slow runs with just a bit of speed work thrown in.

Though my training schedule was on the lighter side of marathon preparation, it was still enough to take over my free time. I gradually stopped practicing guitar and substantially reduced my writing. Normally, I like to take little trips to the mountains on the weekends, but these were also dropped. All of my other hobbies had to exist in the periphery of running. Marathon training, it seems, is hard to incorporate as just one hobby among many. It takes over your life.

My Saturday long runs were especially draining. I would go to sleep early on Friday, not wanting to run tired or hungover the next day. Then I would wake up dreading the run, and I’d do everything I could to postpone it. Normally it took me until 2 to muster the will power to drag myself out of the house, which meant eating an extremely late lunch at around 5 or 6.

Yet when I finally did manage to put on my running gear, tie my shoes, fill up my water bottle, and step onto the sidewalk, habit took over. I had the same basic route for all of these long runs, which I followed without fail. This was the path that runs alongside the Manzanares River, in the south of Madrid. Technically, this consists of two separate parks, the Parque Lineal and the Madrid Río, but in reality it forms a continuous greenspace that extends for as long as any runner could desire. It is also very flat and quite attractive, so I felt very fortunate to have such an ideal training ground nearby.

Keeping myself entertained during these long runs—which often lasted three hours and beyond—became something of a problem. Normally I listen to audiobooks for my runs (my choice for marathon training: Les Miserables), but I found that I could not focus on a book for such a long stretch. Thus, after about an hour I would switch to Bob Dylan’s old radio program, Theme Time Radio Hour, which would be like a second wind after Victor Hugo’s prolixity. But I made sure to spend at least a part of every run without anything in my ears, just focusing on the experience. I thought it deserved at least a slice of my undivided attention.

The long Saturday runs not only made Fridays unavailable for socializing, but usually I felt so tired afterwards that I had little desire to do anything on Saturday night or to go anywhere on Sunday. Long distance running, I must conclude, is very bad for one’s social life.

I am fortunate in that I normally don’t get sick. But I spent most of January and February—my two first months of training—with a persistent cough, which seemed to be related to the long Saturday runs. During the work week, I would gradually feel better. By Friday, I’d think I had gotten over whatever virus was bothering me. But then, after my Saturday run, the cough would return with a vengeance. Though I cannot prove it, I got the strong impression that the long runs were notably weakening my immune system. Heavily breathing the cold winter air for hours at a time couldn’t have helped, either. I must also conclude, then, that marathon training isn’t necessarily even good for your health—at least in the short term.

Marathon runners are often advised to do a kind of warm-up race a month or so before the event. For me, this was a trail race in Aranjuez called “El Peluca.”—the nickname of a local barber who has managed to become a long-distance runner despite his diabetes. The race was 18 kilometers long but with about 500 meters of altitude difference, making it roughly as difficult as a flat half-marathon. My coworker, Carlos—a triathlete—very generously helped me train for this race. He even ran it along with me.

The race left from a park at the edge of town, and we quickly were among the hills that ring the city. After about two kilometers of running on a flat road we reached the path that took us up into the trail, going up and down, over and over, on narrow, dusty trails. Carlos gamely stayed by my side, encouraging me to keep up the pace—which was very nice of him, but also slightly depressing since he made it seem effortless.

I began the race thinking my legs had gotten pretty strong—I had been training for almost three months by then, at much longer distances, often running up hills—but the steep slopes sapped my energy. By the time we ran down the final hill and back onto the road, I could hardly accelerate for a final sprint. I finished with a time of 1:55, in the bottom half. Another of my coworkers, Víctor, actually won the entire race with a blazing 1:19—though admittedly he may not have come in first had another strong runner not gotten lost and gone the wrong way. Trail running has its perils.

(Carlos, meanwhile, was having a great time, as he had found a purple wig that had been hidden in some bushes along the race course. He crossed the finish line with a cartwheel and won a basket full of hair products as the prize for having found the wig.)

During the week after the race, I had pain going all the way up the outside of my right leg, from my calves to my hip. I was afraid that I had given myself tendinitis or some other injury. I took it easy for a few days and stretched. This only helped a little. Then, I tried using a rolling pin to massage everywhere that hurt. Miraculously, that made the pain disappear almost immediately. I have no idea why that worked.

My next long run was what is called a “marathon-simulation.” This is a run of 26 kilometers (not miles) at your planned marathon pace—which, for me, was an unhurried 10 minutes per mile. This time, I actually managed to get myself outside in the early morning, and ran without anything in my ears. It was much easier than I expected. The miles flew by and I finished well under my projected time. Maybe I can do this after all, I thought.

This year, the Easter holidays fell three weeks before the race. I wanted to do something with my free time, but I also wanted to maintain my fitness. So I hit upon the idea of hiking on the Camino de Santiago. I covered about 115 kilometers in five days, from April 2 to April 6, and once again enjoyed the lush Galician countryside. But in retrospect, was this good “training”? I am not sure. I think hiking does benefit your running ability, but I also think it may have been too much distance, too close to the actual race day. The leg pain mentioned above temporarily returned.

With my camino finished, this wrapped up the heavy phase of training for the marathon. The only thing left was the so-called “taper”—basically, relaxing a little. I did not do any runs longer than 10 miles in the two weeks before the race, focusing more on shorter, faster sessions.

I also took the opportunity to try an experiment. One week before race day, I went cold turkey on coffee, tea, and anything else with caffeine in it. The first two days were unpleasant, especially the second. I felt groggy, confused, and almost sick. The closest thing I can think of is a hangover. But my sleep markedly improved. This was partly the goal: to increase the quality and quantity of my rest leading up to race day. The other goal of the experiment was to increase my sensitivity to caffeine so that, when I finally had some on race day, I would be extra sensitive to it. Caffeine, after all, is the only legal performance-enhancing drug.

Of course, in the lead-up to the race, alcohol was entirely cut out. I had to live the pure life.

Three days before race day, I began the famous carbo-loading. This took the form of large spaghetti dinners. The idea is that, by gorging on carbohydrates, you build up a larger reserve of energy in your muscles that you can use on race day. To be honest I really don’t know if it actually works, but I wanted to give myself every possible advantage just in case. Another common piece of advice is to hydrate profusely in the few days before the race. I did this, too—dutifully sipping from my water bottle throughout the day—though I was similarly unsure if it would actually work.

As you can see, I had done my best to optimize my body for the race. I don’t think I had ever tried to be so precise and careful with what I eat and drink, with how much I sleep, with when and how much I exercise. Every variable available to me, I attempted to manipulate. All that remained to be seen was whether it would pay off.

April 23, Race Day. This was also International Book Day, which I took as a good omen.

The night before, I was afraid that I would be too nervous to sleep, so I did everything I could to induce a calm, drowsy state—taking a magnesium supplement, swallowing a pill of melatonin, drinking herbal tea, stretching, meditating. This worked fairly well and, for once in my life, I was able to sleep peacefully before a major event. I woke up at 7 feeling well-rested. Breakfast was a piece of toast and some oatmeal—and, of course, the long-awaited coffee. The chemical worked its magic, and optimism surged up within my brain.

I arrived at 8:30 at the starting line and began to warm up. The area was absolutely packed. More than 30,000 runners had signed up, filling up every available spot. To get my body ready, I slowly jogged around the area—bouncing my legs, raising up my knees, kicking the back of my thighs—just trying to get my heart beating and blood flowing. My ankles, hip, and back popped, which felt good but perhaps was not a good sign. One final trip to the bathroom, and I was ready.

The race was divided into 10 “waves,” and I was number 9, scheduled to start running at 9:30. I entered the gate early, hoping to be near the front of the wave—since, if you’re not, you can get stuck in a huge crowd and be unable to go at your own pace. Directly in front of me was one of the official pacers. These are runners who carry large balloons which have a finishing time printed in bold letters. I suppose they must be pretty experienced runners, since they can reliably finish the race in that time. This pacer had the balloon for 4:15, coincidentally just the time I was hoping to achieve. I positioned myself right behind him at the starting line.

The pistol shot rang out, and we were off. I was in a group of about five runners—two French women, two Spaniards, and me—who were trying to stay close to the pacer. I knew that a 4:15 pace amounted to slightly faster than 10 minutes per mile, which for me is just above my relaxed pace. Even so, the speed felt surprisingly difficult as we wove through the crowd on the Paseo de la Castellana. Finally, after about 10 minutes, my breathing calmed down and I was able to follow without conscious strain.

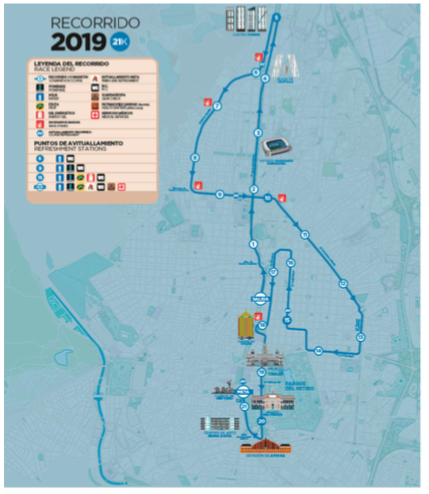

The course took us north, past the famous Santiago Bernabeu stadium, alongside the government buildings at Nuevos Ministerios, through the so-called Gates of Europe—twin, slanting office buildings—and then to the four tallest skyscrapers in the city, the “four towers.”

(You can see a video of the entire course here.)

The road is just slightly uphill during this section, but since I had fresh legs I hardly noticed. Finally, we did a U-turn and started the criss-crossing journey back south. This is where we entered the massive, residential center of Madrid. We were running up and down streets very much like my own—mid-sized apartment buildings, the streets lined with restaurants and shops. So much of Madrid looks so similar that I became disoriented quite quickly, and gave up trying to place myself on the map. But now we were running downhill, and it felt almost effortless.

Though traffic in the city had been severely restricted, pedestrian life went on. The terraces were full of families having breakfast. Parents were shopping with their children. Senior citizens were chatting on benches. It all looked much more pleasant than what I was doing.

But we did have an audience. All along the route, there were people cheering us on. I really have to give anyone credit who spends their Sunday morning clapping for runners. After all, there really is no sport less interesting to watch than long-distance running. Nothing dramatic happens, and you never see the same face twice—just runner after runner, going by at moderate speed. And consider how long the event lasts: from the first wave to the last person over the finish line, around six hours elapse. Even watching long-distance running is a feat of endurance. (Reading about it isn’t much better—sorry!)

I must say, though, that while I considered everyone cheering us on to be slightly crazy, I did very much appreciate the applause and encouragement. It really did help lift my spirits or, at least, distract me in moments of pain. Little kids stuck out their hands for high-gives. Adults held up signs with Super Mario mushrooms on them, to “power-up.” Two men were even offering free pizza, but it didn’t seem like such a good idea to have a slice. Meanwhile, the professional pacer did his best to rile up the crowd, shouting and waving his arms. Having so much social support is partly why, I think, people run faster during races than they do on their own. You feel as if everyone wants you to succeed.

Finally, we took a turn down Calle de San Bernardo, and I realized where we were. The next turn led us directly onto Gran Vía, Madrid’s most famous avenue, and then towards the center of the city, the Plaza de Sol. The size of the crowd surged, and we were surrounded by cheering onlookers. This was the first year that the race went through the center like this, and it felt great to be running through such an iconic part of the city.

As we approached Sol, a series of large black-and-white signs began to warn us that the marathon and half-marathon courses were about to part ways—the half-marathon to the left, with only 2 kilometers to the finish line, and the marathon to the right, with 23 kilometers to go.

Just as we entered Sol, I noticed a group of paramedics and a police officer, who were gathered over somebody laying on the ground, wrapped in a metallic blanket. He must have been a half-marathoner who tried to push too hard during the final stretch of the race. As I passed, I saw his feet moving, so I knew that he was basically alright. But it is true that long-distance running can be dangerously stressful on the body. On March 12 of this year, a young man died after completing a half-marathon in Elche. And four people were hospitalized during the March 26 half-marathon in Madrid. Again, long-distance running may not be the healthiest sport, at least in the short-term.

I tried to put this specter of the perils of running out of my mind as I entered Sol. There were large crowds on either side of us, and a band playing on a stage right in the center. I waved at the half-marathoners, and then turned with some trepidation to the rest of the race. The Madrid half-marathon is actually quite a nice course—reasonably flat and mostly downhill. But the full marathon is considerably more difficult, with long stretches of up-hill and sections with little shade. Besides, Madrid in April is normally quite warm, and by now (around 11:30) we could start to feel the heat. I was sure that this second half would be far worse than the first.

At least it began with some nice scenery. We ran down the Calle Mayor, passing by the Plaza Mayor, the Mercado de San Miguel, and the Casa de la Villa (a medieval building which serves as City Hall). Then we emerged onto the Calle de Bailén and ran right by the city’s cathedral and the Royal Palace. Finally we went up the Calle Princesa, through the beautiful Parque del Oeste, and across the Manzanares River.

All this time, I was still on the tail of my pacer, though several times I fell behind and had to struggle to catch up again. I could feel myself getting tired. I tried to combat it. My coworker, Víctor (the serious runner who won the Aranjuez race), advised me to drink water at every opportunity. This was more frequent than I expected, as there were water stations every 2 or 3 kilometers in the marathon course. I did my best to keep cool and stay hydrated: drinking a glass of Powerade (for the sugar), several gulps of water, and pouring the rest over my head. I also came equipped with energy gels, which are essentially just tubes full of glucose and caffeine that are supposed to keep your energy levels up during a long race.

Even with all of this chemical help, however, I felt myself flagging. After stopping at one water station, I looked up and saw that my pacer was about 50 meters in front of me. Try as I might, I couldn’t catch up. Soon the balloon was barely visible down the track and I had to resign myself to running a slower marathon. Admittedly, this was a kind of relief, since it allowed me to go at a more comfortable speed. But as I neared kilometer 26, I found that I had to exert effort even to keep going at this more modest pace.

Meanwhile, another one of my coworkers, Pedro, passed me. (I guess I have a lot of athletic coworkers.) He said hello and disappeared down the track, on his way to complete an impressive 3:55 marathon.

Any hope of a strong finish fell apart once I reached the Casa de Campo. Here the path traveled uphill for kilometer after kilometer, often on dirt roads with little shade. I could not stop thinking that I had entered the Valley of Death. Many runners around me were experiencing this same difficulty, slowing down considerably or just walking, a phenomenon known as “hitting the wall.” This is when you use up all of your body’s glycogen (the way your body stores carbs for later use), which typically happens at around mile 20 (or kilometer 30).

According to the sports writer Fitzgerald, this happens to about 70% of runners who attempt a marathon, so I saw it coming. But I did not expect it to feel the way it did. I thought that “hitting the wall” would mean feeling dizzy, lightheaded, and totally out of energy. Instead, I felt reasonably alert and clear-headed, but my legs cramped up and began to feel extremely heavy. It felt as if my muscles had done as much as they could and were totally worn out. It got worse: as I ran up a cruelly steep hill, painful spasms shot up both my legs, which was concerning to say the least. I began to worry—perhaps irrationally?—that I was nearing my legs’ breaking point, and that I had to back off to avoid an injury.

Under these circumstances, I slowed down more and more, every kilometer more sluggish than the last. I was not alone in my predicament: by around mile 21 (kilometer 35) almost everyone around me was walking, at least part of the time. I considered walking for a bit to regain some strength, but I was afraid that if I stopped running I wouldn’t be able to start again. So instead, I just ran at a snail’s pace, so slowly it was generous to even call it running. I was barely going faster than those walking around me. This, naturally, had the effect of stretching out the final miles to an agonizing extent. Rather than passing a kilometer marker every six minutes, it was taking me eight.

Though my stomach felt absolutely full, I dutifully stopped for my last drink of water, pouring half of it over my head. My eyes cleared in time for me to see the pacer for 4:30 passing by. They were not going very fast, but there was no way I could hope to catch them in my state. Not only had I missed my goal of 4:15, then, but I had even failed with my backup goal of 4:30. Yet I was much too exhausted to be upset. Indeed, I was surprised at how cheerful I felt. From what I’ve heard, many runners feel quite depressed at this point in the race. But if my body was breaking down, I still had enough mental strength to keep myself chugging along.

I was nearing the end now. The course took us through the Delicias neighborhood, down the Calle de Méndez Álvaro, and finally past Atocha station and up the Paseo del Prado. There were more and more spectators at every turn, swelling into a real crowd as we neared the end. Once again, I was very grateful to everyone cheering, though I admit I felt pretty ridiculous as I inched along, dragging my legs behind me, while people acted as if I were some kind of athlete. I certainly did not feel like an athlete at that moment.

The run up the Paseo del Prado felt endless, the upwards slope making me slow down to a barely perceptible forward movement. But eventually, inevitably, the end came into sight. I passed the Prado Museum, I passed the Fountain of Neptune, and finally the enormous Palace of Cibeles came into view. Just beyond, I could see the inflatable gate that marked kilometer 42, the finish line now directly ahead. I felt a surge of emotion when I finally saw it, and surprised myself by almost crying. But, realistically, I think I was too dehydrated for tears. In any case, the emotion passed almost instantly and I felt mainly relief as I attempted—unsuccessfully—to speed up for a final sprint.

I stumbled over the finish line. I was finished. Volunteers handed me a medal and a bag of food, and ushered out of the runners’ zone. Though I should have been enjoying my “triumph” (or at least savoring being able to stop running), I was quite worried at this point about whether I would be able to walk to the train and make it home without incident. I really didn’t know if my legs would take much more. But this fear was unfounded: I made it back to my apartment without incident, peeled off the sweaty clothes, and assessed the damage.

Everything in my pockets—my keys, my headphones, my phone—was sticky from the energy gel packs, which had spilled after I opened them. One of my toenails was bruised and discolored (even though I made sure to cut them beforehand!). On my other foot, I had a large and painful blister. And I had small cuts from chafing all over my body. Getting into the shower stung like crazy.

The rest of the day, I just sat on the couch, eating pizza and ice cream. I did not feel triumphant or euphoric, but I was done. My final time: 4:41. Of the 9,101 runners who competed, I was number 6,139—decidedly in the bottom third. But I was done!

I have already written far too much about this race. If you are still with me, you deserve a medal yourself. Now, I only want to address a few more points.

First, could I have avoided the dreaded wall? There were a few things I could have done differently on race day. I could, for instance, have gone at a slower pace for the first half, and thus have conserved more energy for the second (though it is far from certain I would have run the entire thing faster than way). It’s also possible that I didn’t take enough fuel. Many runners gulp down an energy gel every 30 minutes, with the express aim of not depleting one’s glycogen reserves. However, I am a bit skeptical that this actually works. Doesn’t it take some time for the body to process and absorb calories? Perhaps the most obvious answer is that I could have trained more. But that will almost always be true.

Realistically, even with all the tweaking in the world, I don’t think I could have done much better than I did. I am not built for speed.

Another question I am sometimes asked is: What do you think about during such a long run? The honest answer is: not much. For such a simple activity, running takes a lot of attention. Indeed, I find that it is quite meditative, and I don’t often catch my mind wandering far afield. Besides, while running, I hardly have the energy for anything more complex than a passing observation. This, I think, is actually one of the primary benefits of running. It clears the mind.

Running a marathon seems to have reputation as something admirable and noteworthy in our culture. It is the mark of somebody determined and goal-oriented. Now that I’ve run one, I can ask: is that reputation justified? Certainly, training for a marathon requires consistency and discipline. But the same can be said of many other activities—learning an instrument, writing a novel, painting a portrait, or simply having a job and raising a family. And considering the huge time expenditure and the questionable health benefits (probably training for shorter races is just as good for you), it is difficult to argue that it is an especially good use of one’s time. Thus, I am not convinced it deserves its reputation as an admirable challenge.

Last, I must ask myself: Will I ever do this again? I cannot say the experience was overwhelmingly positive. It was time-consuming, often painful, and I achieved unremarkable results. And, again, I am not even sure that I am now any healthier than I was before I started. Just a little skinnier.

Even so, I may be betraying the mentality of an addict when I say that I will almost certainly run another marathon. Though running is the simplest sport imaginable, as you can hopefully see, doing it to the absolute best of your potential requires a great deal of thought, effort, and focus. It is a kind of massive experiment you are conducting with your own body. I guess all this is to say that I am hooked, and eager to see if I can improve. But in the back of my mind, I know that running is, ultimately, just a form of exercise—a component of the life I want, but not its main focus. After all, I have a blog to write.

(Photo credits: All of the photos used in this post, except that of me and Carlos, were taken by professionals at the event and purchased at Sportograf.com.)