The train was boarding in Budapest’s Keleti station. An elderly Hungarian woman, speaking broken German, asked me to help her with her bags. I did so, and then took a seat on the train. We were bound for Vienna.

The ride was not quite as uneventful as I had hoped. For one, I soon discovered that the ticket I purchased online (for a very reasonable price) did not come with a seat number. Thus, anytime the train made a stop, there was a chance that I would be booted by someone who did have a reserved seat. This made the trip considerably less relaxing than it could have been. Then, the train stopped at the Austro-Hungarian border, and—surprising in Europe, where borders are so permeable—a troop of armed border agents got in and started systematically checking people’s passports. We were also instructed to put on our special N95 masks, mandated at that time by Austrian law for indoor spaces. Everybody complied, though it did seem rather silly to be putting on a mask after breathing in the air for well over an hour.

(I think somebody should examine the relative COVID rates between Hungary, which had no restrictions at all, and Austria, which not only had a mask mandate, but required the heavy-duty N95 masks. It is a natural experiment.)

A little after noon, the train pulled into the Vienna Hauptbahnhof. I took a metro into the city center, deposited my luggage in one of the many storage lockers, and then set out to re-discover Vienna. My first priority was lunch. For this, I headed to a Viennese staple, Buffet Trzesniewski (the name is Polish, I believe) for some of their tiny little open-faced sandwiches. I got five—with various combinations of egg, fish, mayonnaise, and bacon—and every one was delightful. Indeed, I admit that the description of the food did not sound at all appetizing to me, but each sandwich was scrumptious. I particularly liked the small glass of beer, called a “pfiff,” to wash it down.

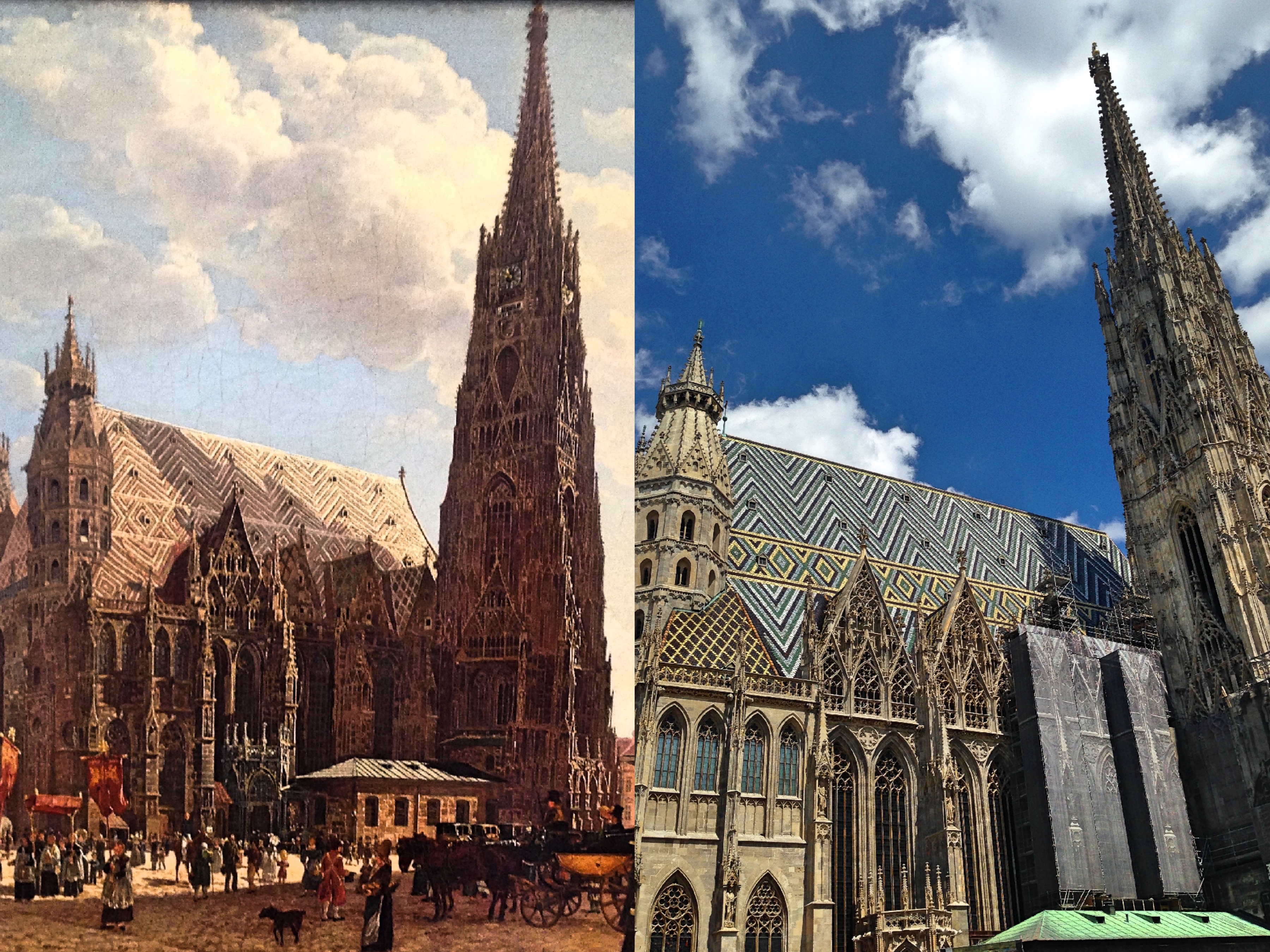

Reinforced, I was ready for Vienna’s cathedral. The last time I had visited, which was in 2018, I had balked at the entry fee for the grand church, and contented myself with a peak inside. This time, I resolved not to be so cheap. The ticket comes with the option of an audio guide. But at the time of my visit, I was in the throes of an obsession with Rick Steves, and instead elected to use his free audio guide. I’m sure it comes to the same thing, although my choice allowed me to enjoy the nasal strains of his high-pitched voice.

The roots of St. Stephen’s Cathedral go back to the Romanesque period, though the church, as it stands today, is mostly gothic in design. The visitor will likely notice two things immediately: first, the majestic south tower—a classic gothic skyscraper—and second, the colorful roof tile mosaic. Perhaps the colors are so vibrant because it was installed after a great fire gutted the cathedral and destroyed its roof in 1945. The retreating German commander actually disobeyed orders to destroy the building, but a fire caused by looting nearly did the job, anyway.

This fire also destroyed many of the bells in the cathedral, including the famous Pummerin, which had been cast from the canons of defeated Turkish invaders in 1705. Thankfully, a replacement was cast and installed in the shorter, but stabler, north tower. This new Pummerin clocks in at over 20,000 kg, the third largest bell in Europe. (For context, the Liberty Bell weighs just 940 kg, not even half of a tenth as much.) It can only be heard on special holidays and other festive occasions, so I was not lucky enough to be the person for whom the bell tolls.

(On the topic of big bells, even though it has nothing to do with Vienna, I cannot help mentioning the story of the largest bell ever made, the Great Bell of Dhammazedi. It was cast in present-day Myanmar and weighed an unbelievable 300,000 kg—or, if you’re American, over 300 Liberty Bells! The great bell was stolen in 1608 by the Portuguese “adventurer” Filipe de Brito, who hauled it by elephant to a raft, hoping—of all things—to melt it down to make cannons. His scheme unwound when his raft sank, taking his flagship with it, as the incredibly heavy bell proved to be too… well, incredibly heavy. De Brito was captured and executed by being impaled on a stick. There have been many attempts to find the bell under the river, but so far it has eluded detection. In any case, I have no idea how it could be lifted.

Anyway, back to the cathedral.)

There are several highlights on the tour around the cathedral. In one corner of the cathedral is the stately tomb of Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor. Like so many kingly sarcophagi in Europe, this one contains the bones of a Hapsburg. Another is the beautiful Neustädter altar, a massive, folding wooden piece that is a pentaptych rather than the traditional triptych. When it is fully opened, it reveals a marvelous series of reliefs; but when folded up—and it often is—the altar reveals only an uninspiring series of paintings.

The pulpit, thankfully, is always on display, and it is marvelous. It is a perfect example of the Gothic style—gorgeous, meticulous, intricate, and heavily symbolic. As in so much Catholic art, the entire worldview seems to be represented using a panoply of saints and signs (many of them animals).

The architect of this stony florescence must have known that he had created a masterpiece, as he included a self-portrait below. You can see him peering from an open window, his compass in hand. This is known in German as the Fenstergucker (window-looker), and it is one of the most winsome self-portraits I can think of. Nearby, on a wall, is a similar figure. This time he is holding a compass and a framing square. And, like the builder himself, he symbolically holds up the cathedral at the base of an arch. By the way, it is not known who exactly this master builder was. The two prime candidates are Anton Pilgram and Niclaes Gerheart van Leyden.

It was getting late now, so I decided to visit the Weltmuseum Wien, which was open until 7pm on the day I visited. This is a large and rather miscellaneous museum located in one wing of the Hofburg Palace. The collection includes a great deal of medieval arms and armory—some of it quite beautiful, though the signs were only in German so I couldn’t learn much—as well as a smattering of objects of “anthropological” interest (meaning, from cultures outside of Europe). But I spent virtually all of my time in the collection of musical instruments.

This must be one of the greatest collections of this sort in the world. For one, there is an assortment of famous instruments—either because of who made them, or who played them. There is an Amati violin, for example, and a piano that was played by both Robert and Clara Schumann, as well as Johannes Brahms. But there are also many instruments special for their particular beauty or unusual design. After all, there is nothing inherently special about the design of a flute or a violin; anything that makes noise can be an instrument. Thus, there are bizarrely twisting horns and oddly shaped stringed contraptions. The collection goes even beyond instruments. There is a table specially designed to hold music for a string quartet; and another table, belonging to the bishop of Passau, is decorated with musical notation.

This visit put me in the ideal mood for my next destination: the Wiener Staatsoper (Vienna State Opera). Now, it is possible to buy standing-room only tickets a few hours before a performance. But I doubted that I could stand through an entire performance, and so opted to buy a cheap seat (for about $15). This price would have been worth it just to be given the privilege of exploring this fine building—a beautiful neoclassical construction fit for the Austro-Hungarian Emperor himself. Lucky for me, Carmen was playing during my visit, and I was able to see (or, rather, hear, since my seat had limited visibility) that marvelous opera performed with great panache.

In short, though I had arrived around midday, I managed to have quite a wonderful day in the Austrian capital.

As my Airbnb was nearby, I decided to start off my next day by visiting the great Schönbrunn Palace. According to Rick Steves—who would know—this is the one palace in Europe that can rival Versailles. But you would not think it from the outside. Whereas Versailles’s exterior is vast and resplendent, the Schönbrunn is, by palatial standards, relatively modest—painted plain yellow, with few frills. But if you pay the (somewhat steep) entry, you will see that the interior is indeed as sumptuous as could be desired. Even so, if you ask me, the best part of the visit is a (free) stroll through the palace gardens, which are vast and lush

Two figures loom over the Schönbrunn: Franz Joseph I and his wife, Elisabeth. Franz Joseph, the longest-reigning emperor of Austria, was born in this palace; and it is also here that he died, in 1916, at the age of 86. His wife, Elisabeth—affectionately known as “Sisi”—was quite a colorful figure. Highly neurotic and hugely dissatisfied with court life, she spent much of her time traveling around, unaccompanied by her husband. But when she was in Austria, she often retreated to this palace. Like so many public figures during this time, she was assassinated by an anarchist in 1898, making her the longest-reigning Austrian empress.

(Though it is not directly related to the palace, I cannot help inserting a little story. The marriage of Franz Joseph and Sisi produced only one son, Rudolph. This made him heir apparent to the throne; but in 1889, he died in gruesome murder-suicide pact with his lover, the 17-year old Mary Vetsera. Rudolph’s motivations are still unclear, but his marriage was very unhappy. This led to his cousin, Franz Ferdinand, becoming the new heir apparent. And, of course, his murder at the hands of Serbian nationalists kicked off the First World War, which eventually brought down the whole Empire.)

Palaces, even beautiful ones, tend to put me in a foul mood. (I suppose they bring together too many things I detest—obscene luxury, arbitrary power, and huge crowds of tourists.) To recover my spirits, I went to another of Vienna’s world class museums, the Albertina.

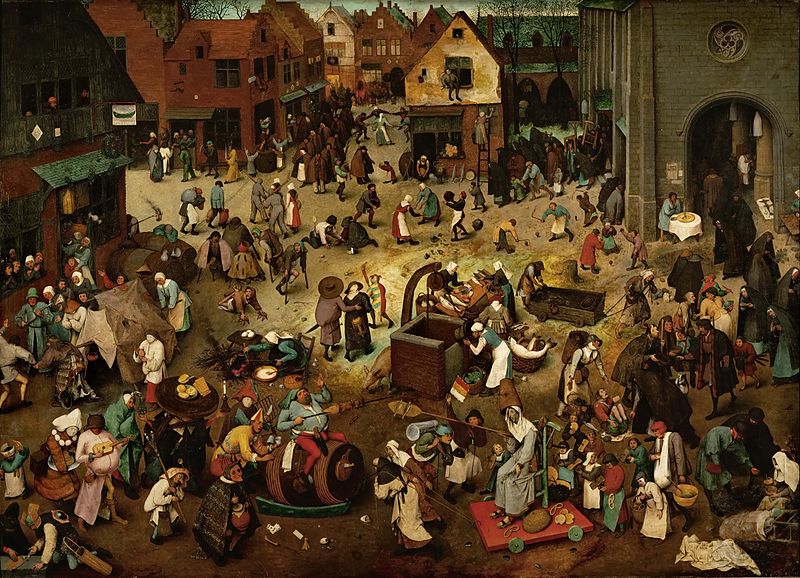

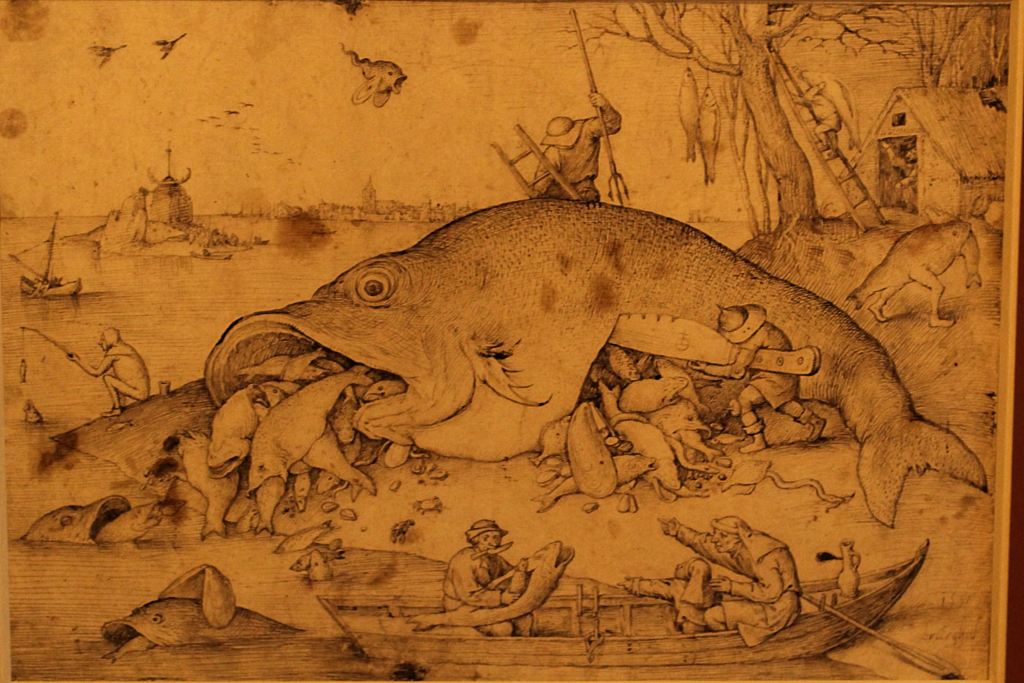

Located in another erstwhile palace (Vienna is full of them), the museum is named after Duke Albert, a Hapsburg Prince and art collector who used to live here. A visit to the Albertina is a complete experience. You begin by walking into an ornate foyer and exploring some of the palace rooms. Then, you get to the core of the museum: the collection of prints and drawings. Few, if any, museums in the world can rival the quality of these works. There is Dürer’s exquisite watercolor of a rabbit, Da Vinci’s study of the last supper, and a monstrous fish disgorging its insides by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. A study for Hieronymous Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights is on display, as is a muscular male nude from Michelangelo.

This riot of brilliant draftsmanship would be more than enough for any art lover. But the museum also has a substantial collection of Impressionist and Post-impressionist paintings. Indeed, with works by Picasso, Monet, Cézanne, and Magritte, this collection alone would also make a fine museum. I was particularly interested in the Munch exhibit that was on display during my visit. Aside from his famous Scream, I had known close to nothing about the Norwegian painter, and it was a pleasure to witness his artistic development.

Right next to this museum is another classic Viennese attraction: the Wurst stand. It is recognizable from the large green rabbit on top (modeled after the Dürer painting). There, you can order from a range of delicious sausages for a quick and filling meal. Vienna is, of course, full of sausage vendors, though this one is the most famous.

My next destination was far outside the city center. To get there, I took the metro to the Wien-Heiligenstadt station, in the north.

Though Vienna is a beautiful city, it was a relief to be in a more humble, ordinary neighborhood, with no crowds to speak of. Vienna is so grand, so stately, and so full of tourists that it can feel like one big, outdoor palace. Now, at least, it felt like I was in a place where ordinary people lived. I wandered around a little, stumbling upon a little park named for Beethoven, and eventually decided to have lunch in a place called Mayer am Pfarrplatz. Though the place had seats for upwards of 100, it was mostly empty, and I was put at a table in the patio. I ordered the cordon bleu with the Austrian potato salad (that means vinegar and no mayo), and found it to be delicious beyond belief. The white wine was also stupendous.

While I ate, the waitress informed me that Beethoven used to live in the adjoining house. I later learned, however, that Beethoven lived in dozens of different apartments throughout his life, so this might not be such a claim to fame. Still, thinking of Beethoven did improve my dining experience.

I left in a satisfied stupor and continued to climb up the hill into the vineyards beyond the city. In no time, I was completely surrounded by fields of grape vines, and soon I came upon one of the famous wine stands. It was an Edenic vision: picnic tables full of happy people, all holding glasses of crisp white wine. I bought myself a glass and sat down. The view of the Danube and the city beyond was nearly as intoxicating as the drink; and the wine was scrumptious—light, dry, and refreshing. Indeed, I think I enjoyed those couple hours just sipping wine outside an order of magnitude more than I enjoyed visiting the palaces and museums. I highly recommend it.

This pretty much did it for my day, as far as sightseeing was concerned. After drinking so much wine, I went back to my Airbnb and had a short nap. Then, as a form of repentance, I put on my running shoes and went to the Donauinsel.

Much like Budapest, you see, Vienna has its own island park. Unlike Budapest’s Margaret Island, however, Vienna’s island is artificial. It was originally created as a form of flood control, but accidentally became the most popular recreational area in the city. The island is narrow and long. If you ran from the southern to the northern tip, and then back again, you would complete a full marathon. Yet it only takes a few minutes to go from one side to the other. When I went, the park was full of cyclists, joggers, and people out for a stroll. And for my part, I quite enjoyed running along the gravelly paths with the cool breeze coming off the water.

I woke up in a melancholy mood, as it was the last day of my trip. Lucky for me, however, my flight back was quite late in the day, so I had time to do some sightseeing. In cases like these, luggage lockers are an essential resource. I checked out of my Airbnb, stowed my bag, and was first in line at the Café Demel to get breakfast.

Now, Vienna is famous for its cafés, and justly so. They maintain the old musty smell of the Austrian Empire—with ritzy decorations, bow-tied servers, and a rack of newspapers. Demel is particularly attractive, filled as it is with sweets wrapped up in gift boxes. For breakfast, I ordered the obligatory Viennese classic: Sachertorte. This is a kind of dense chocolate cake with a bit of apricot jam in the center. To drink I ordered a “melange,” which is what the Viennese call a cappuccino for some reason. It was quite good—though, I must say, rather pricey.

From there, I got on a tram. My destination: Vienna Central Cemetery. This is an enormous cemetery which, its name notwithstanding, is on the outskirts of the city. With three million buried, it is one of the most populous cemeteries in the world. Though not as beautiful as Père Lachaise, this burying ground is an essential place of pilgrimage for music lovers. For it is here that the esteemed bodies of Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert, Strauss, and Salieri are interred.

Now, at first glance it may seem strange that Beethoven, who died in 1827, or Schubert, who died the following year, should be buried in Vienna Central—which, after all, opened in 1863. Their presence is due to a kind of marketing ploy. The cemetery was originally unpopular because of its distance from the city center, so they decided to relocate some revered corpses to make it more of a “destination.” Clearly, it worked.

Luckily for the visitor, all of these famous composers are right next to one another. For me, it is a subtly powerful experience to stand before the graves of such legendary figures. Their reputation is so enormous that they hardly seem real. But when you are standing above their bones, their humanity is palpable; and their achievements become all the more impressive for being made by somebody no different, in essence, from myself.

Aside from the musical greats, this cemetery is also interesting because of its interdenominational nature—not so common in Europe. There are sections for Catholics, Protestants, Greek Orthodox, Jews, Muslims, and even Buddhists. I was interested to find a large section devoted to Soviet soldiers who died during the Second World War.

After taking the tram back to the center, I only had a short time before I had to head to the airport. Since I was then in the throes of a Rick Steves addiction, I decided to follow his walking tour of the city. This proved to be a good choice, as it led me past a few interesting things I had missed. For example, I took some time to admire the enormous and bulbous Plague Column, which was erected in 1679 after a terrible epidemic. Strangely, the Baroque monument does capture (though perhaps unintentionally) something of the horror of a deadly pestilence.

I also was shown something I had overlooked before: the Memorial against war and fascism. This is in the Albertinaplatz, right near the museum. Designed by Alfred Hrdlicka, it consists of several free-standing sculptures made using rock quarried in the Mauthhausen mine. The monument commemorates victims of the Holocaust, as well as the innocent victims of all wars. In this spot used to stand a residential building that was struck by an Allied bomb in 1945, killing many hundreds of people—many of whom are still buried under the ground.

The “tour” ended at the Hofburg palace, the main residence of the Habsburgs. (The Schönbrunn was a summer palace.) It was strange to contemplate such a vast and monumental building which now serves no purpose except tourism. Like Vienna itself, the palace is a kind of head without a body—the wreck of foregone imperial grandeur.

But you cannot feel bad for the Viennese. After all, their city is consistently rated the most livable in the world. After just a few days, I could see why.