(Continued from my post about Cáceres.)

Mérida has a long and noble history. Founded in the year 25 C.E. as a Roman Colony, during the reign of Octavius, the city was the starting point of the Vía de la Plata (the Silver Way)—a major Roman road running from south to north—and the capital of the Roman province of Lusitania. The city is an hour’s drive west of Cáceres. As usual, we were taking a Blablacar. Our driver was a young man from Seville—laid back, sociable, patient with our Spanish—and the drive proceeded very pleasantly.

The drive became doubly pleasant when a rainbow appeared to our left. It was interesting to see how the rainbow seemed to move across the landscape with us as we drove. I have this deep-rooted idea from watching cartoons as a child that a rainbow is a stationary object (how else could Leprechauns bury their pots of gold at the end?). But of course that’s not true; rainbows are optical illusions caused by the refraction of light through water droplets in the air, and thus appear at a different locations to each individual viewer. I suppose I’ll have to play the lottery if I want a pot of gold.

Soon we had arrived. Our bags tucked away, we began to explore the city. By now it was already rather late; all the monuments were closed, and the sun would be setting in an hour. With few options, we decided that we would stroll along the Guadiana River. The Guadiana is the bigger of the two rivers (the other is the Albarregas) that run through the city. The forth largest river in Spain, further west it forms part of the border with Portugal.

(By the way, the prefix Guad- can be found in several other Spanish place names, such as the Guadalquivir, the river that runs through Seville and Córdoba; the Guadarrama, a mountain range near Madrid; and Guadalajara, an old city in Castilla La Mancha. This prefix is a Castillianization of Arabic.)

A park ran along the riverside, green and splendid. Stray cats hid among the bushes, and teenagers sat and chatted on the benches. The river was calm and clear; the overhanging trees were reflected on its surface in the waning daylight. We walked until we reached a bridge, and then climbed a stairwell hoping to cross the river. But once we got to the top, we both gasped.

Half the town was gathered in the square, under the walls of the old Moorish fortress. The people were having an Easter Parade.

The most immediately noticeable thing—for an American, at least—is that it looks like a gathering of the Ku Klux Klan. Of course, the Spaniards created their costumes first, and thus it is absurd to associate them with American racism. Nevertheless, the first time I saw it with my own eyes, I couldn’t help feeling uneasy.

The unease passed quickly, however, and soon I was wholly absorbed in the spectacle. Rows and rows of hooded figures were lined up, some in red, some in white, each of them carrying a stalk of wheat. Among these were dozens of children, who carried little bags full of candy with them; as they walked by, they handed each passerby a treat. Behind the hooded figures was the float. On a large platform a life-sized figure of Jesus was seated on a donkey for his triumphant entry into Jerusalem.

Floats such as this—typical of Semana Santa (Holy Week) in Spain—are carried on the shoulders of a team of men, who huddle underneath, hidden under a veil. It must be heavy. As I watched, the float slowly lurched into motion, step by slow step, plodding like a giant through the town.

Behind the float was the marching band of brass instruments and drums. The music was very simple, and very loud. The snare drums beat out a slow, methodical march rhythm. Over this, the band played a somber sequence of minor chords—a sour, out of tune, tremendously tragic sound that conveyed a sense of overwhelming loss. Sometimes a trumpeter would play a call-and-response with the rest of the horns, squeezing out a strangled series of shrill notes, to be answered by the violent blare of the other players. If you think I didn’t liked it, you’re mistaken; it was music with pathos.

We stood and watched the Holy Week procession for over an hour. I feel privileged to have seen it. Unlike any American tradition, the Semana Santa traditions in Spain give the overwhelming impression of authentic age—as if they have been celebrated the same way for centuries. One feels that one is looking into the depths of history. In stark contrast to the commercial holidays I am accustomed to, the parade had a gravity and solemnity that was deeply moving.

But now it was dark, and we were hungry and tired. After a quick bite we went to sleep.

The next day was Monday. This was to be our only day full in Mérida, so we had lots to see. As I mentioned, Mérida was an important city in Hispania (Rome’s name for Spain). Consequently, some of the finest Roman ruins in Spain, and perhaps anywhere in the world outside Italy, can be found here.

Visitors to the Roman ruins of Mérida have the option to buy combination tickets, which include six sites. This is what we did. Then we went to the two jewels of the city: the Theater and the Amphitheater, located right in the center of town.

The visit took us to the amphitheater first. This is a like a smaller version of Rome’s Colosseum—though it was still a massive construction, big enough for 15,000 spectators. Many of the entranceways into the area are still perfectly useable, the Roman arches still holding strong. Other parts of the building are in various states of decay, allowing me to see the different layers of materials used in the building. One thing I learned—and I’m mildly ashamed I didn’t know this before—was that the Romans had bricks. Indeed, the bricks looked so neat and pristine, their color still bright red, that I found it hard to believe that they were original.

The years had been hardest on the seats; most of them are reduced to rubble. Apart from that, however, the preservation is astonishing. Our visit took us through a long tunnel, the main entrance. On either side of the walkway, cardboard cutouts of gladiators are standing guard; beside these are captions of information, explaining the typical armaments of the different types of gladiators. I had thought there were only two or three types of gladiators, but apparently there were a dozen or more, each with their own distinct weaponry. Some had tridents and nets, some had rectangular shields and short swords, and some had small circular shields, heavy helmets, and daggers.

On a stone in front of the box seats reserved for government officials is a faded inscription: AUGUST. PONT. MAXIM. TRIBUNIC POTESTATE XVI. (I myself couldn’t read it, but there was an informational plaque nearby.) From this we learn that this amphitheater was built during the reign of Caesar Augustus, around the year 8 BCE to be precise. To put that in context, the Colosseum was built about eighty years later, in 75 CE.

I tried in vain to imagine what it would be like to fight for my life in front of hundreds of cheering people, and gave up. It is a chilling thought to realize that this splendid architectural marvel was built so that the exploited citizenry and overfed nobles could watch slaves kill each other. It is yet another proof that great art can be produced for nefarious ends.

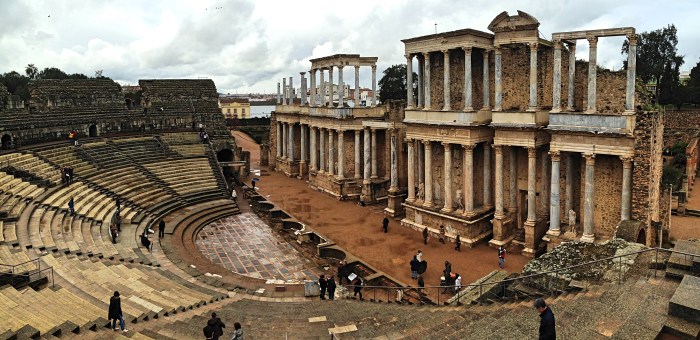

After our fill of pictures we went to the next stop, the Roman theater. It was even more impressive than the amphitheater we had just passed through: it was gorgeous.

The theater holds about 6,000 people. First built in around 15 BCE, and majorly renovated about 200 years later, it consists of a semi-circular stadium of seats surrounds a central stage. At first glance the seats looked to be in much better condition than the seats in the neighboring amphitheater; but this was an illusion created by stone-colored plastic coverings. (Plays are still performed here so they need working seats.) In the middle is a semi-circular open space, and beyond that, on a raised platform, a larger rectangular space: this was where the magic happened. But the real attraction was the structure behind the stage.

On each side, resting upon two levels of ten elegant Corinthian columns, was a wonderful façade that served as a backdrop for the ancient theater productions. This is called the scaenae frons, a normal fixture of Roman theaters. It had three doors, one in the center and one on each side, that allowed the actors to enter and exit the stage. The columns themselves were lovely, carved from delicately textured gray and white marble. Standing in the nooks of these columns were Roman statues (the originals are on display at Mérida’s Museum of Roman Art; these are replicas) of gods and heroes, with flowing robes and ornate armor.

I feel a powerful sense of helplessness in moments like this, when faced with something so beautiful and so historic. What am I supposed to do? I take pictures, I wander around, I sit, I stand, I stroll, I do my best to examine and appreciate. I feel a sense of awe at the age and splendor of the place, but what am I supposed to do with this feeling? I wish that the experience would humble me, will put things in perspective, and thus ennoble me; but of course the person who walks out of the monument is still the same petty, neurotic person who walked in.

I hoped to visit the city’s Museum of Roman Art next, but here I realized that I had planned my trip poorly: we were there on the only day the museum is closed, Monday. So we left to go find some more Roman ruins.

Luckily, Roman ruins were not in short supply. In just ten minutes we came upon the so-called Temple of Diana. This is something of a misnomer, as the temple was actually dedicated to Augustus. In any case it is an impressive sight; a marble lintel sat atop several towering columns. Behind the remains of the temple is affixed an old Renaissance-style house. Apparently, some rich knight decided that it would be nice to live next to the old ruins. The house was elegant enough, but the final effect of the house and the temple was somewhat incongruous. If memory serves, the government considered knocking the house down; but finally decided that it was important enough to merit preservation.

Next we went to the Alcázaba. As its name suggests, this is an old Moorish fortress; it stands next to the Roman bridge, so as to guard the old entrance to the city, and apparently was built over the remains of an older, Roman fortress. This fortress came in handy to the Moors, as they faced several uprisings. The walls are tall and thick, and could have easily withstood all but the most organized attacks.

The entrance fee was included in our combination tickets, so we walked right in. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much to see inside the walls. I imagine that the place was previously full of military barracks and other martial necessities, made out of non-durable materials like wood, which have since disappeared. The only exception to this was the stone cistern. This was a square building that stands in the center of the fortress. There is nothing inside except a long ramp that leads deep underground. At the bottom is a pool of clear, blue rainwater where, surprisingly enough, some fish make their home. But what do they eat?

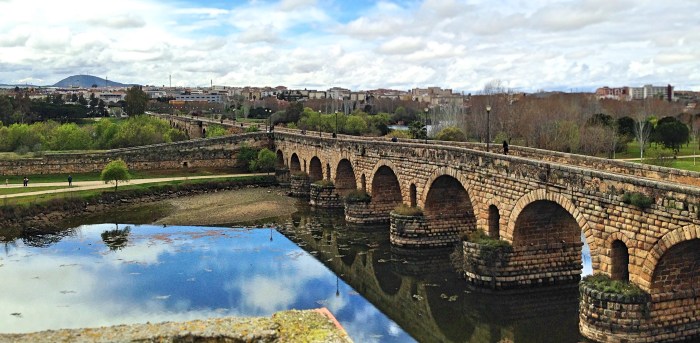

Adjacent to the fortress is the Roman Bridge. This bridge is quite similar to the Roman bridges I had seen in Salamanca and Córdoba: a stone road built over a series of arches, not more than fifty feet over the water. But the bridge of Mérida does have the distinction of being considerably longer; indeed, it is the longest surviving bridge from ancient Rome. The bridge stretches well over 790 m, or 2,500 ft—a stupefying achievement of engineering. The Romans knew what they were doing.

GF and I walked to the other side of the river, and towards the other major bridge of Mérida, the Puente Lusitania. This is an attractive, modern bridge, designed by the architect Santiago Calatraba. The form of the Puente Lusitania is dominated by a big, great fin, like the back of a whale. Its completion in 1991 finally allowed the city to close the Roman Bridge to vehicular traffic. In other words, the only bridge linking both halves of Mérida until 1991 was a bridge built by the Romans.

(The only other bridge across the Guadiana is the railroad bridge, a triangulated structure of cast iron beams riveted together, designed by an Englishman named William Finch in the nineteenth century. The three bridges of Mérida, taken together, are a lovely study in contrasts.)

Our next stop was the Circus Maximus. This was on the other side of town; we had to walk about half an hour, all the way through the city center and through a tunnel under a highway to get there. Again, our tickets included this visit, so we walked right in.

In truth, there wasn’t much to see. It is a dilapidated stone wall (previously, rows of seating), that surrounds an oval-shaped grass field. The only impressive thing about the monument was its size: it’s huge. This was, of course, because chariot races cannot be carried out in closets. We walked around the grassy field for a few minutes, while I tried in vain to imagine what a chariot race would look and feel like, the horses stampeding in a confused heap, the wheels rattling, the whips cracking, the men shouting, the crowd screaming.

Outside the Circus Maximus were the remains of an old Roman aqueduct, the Acueducto de San Lázaro, one of the three Roman aqueducts of Mérida. Compared with the extraordinary aqueduct of Segovia, this one was rather short—only about 20 to 30 feet. It did go on for quite a ways, however, eventually extending over the other river of Mérida, the Albarregas.

We followed the aqueduct for a while, across the river and into a park, until the aqueduct disappeared over a hill. Then, we broke off for our next destination, the last site included in our tickets: the Casa del Mitreo.

This is an archaeological site that consists of the remains of an entire Roman housing complex. Understandably, you can’t go in; the visitor walks around a platform raised above the ruins, allowing you to peek inside the rooms from above. The complex was quite large; either it was one very rich family, or several families of more humble means. I don’t know, because all the information panels were written in very small font, in Spanish, and there was a crying kid nearby that kept breaking my focus. Oh well.

Most notable were the impressive floor mosaics, beautifully preserved. My favorite was a floor that had three concentric patterns: an outer pattern of criss-crosses, a middle pattern of rectangles, and an inner pattern of an intricate labyrinth. Floor tilling hasn’t advanced much in the last two thousand years, it seems.

The sun was setting now, and both of us were exhausted. We had been on our feet all day, crisscrossing all over town. But we had one final thing see: the Acueducto de los Milagros, or Aqueduct of the Miracles. This meant yet another walk through town, which we dutifully made, painful and blistered as my feet now were. It was worth it.

This aqueduct is massive, about 25 m, or 80 ft tall, standing on three rows of arches. It is partly in ruins now, scarred by the tooth of time, but this only lent it a special majesty. The sun was setting, shinning directly onto the aqueduct, making its brick construction glow a rusty red. All around was a park, where families were talking and laughing. GF and I sat on a bench, resting our aching limbs, staring up at the towering ruin. It was so impressive and so lovely that soon I felt myself full of energy again, ready to drag myself through a dozen more Roman monuments.

Soon the sun was setting. We limped back into town, and were again greeted with a surprise: they were having another Easter Parade. This time the crowd was gathered in front of the doors of a church. Just as we got there, the procession started to exit the building, walking with slow steps to the beat of another doleful march. We watched it go for a while, and then went to feast on beer and cheap sandwiches. Our trip was over. We would be going to Lisbon early next morning, but that’s for another post.

I’m not sure I’ve had a better day in Spain, and that’s saying something. Do visit Mérida. It is an extraordinary place.

Now it was time to see what we came for: the Cathedral of Burgos, La Santa Iglesía Catedral Basílica Metropolitana de Santa María. We walked out of the church and looked up. It was stupendous. The cathedral of Burgos is one of Spain’s lesser known treasures, at least to outsiders. Even greater than the Cathedral of

Now it was time to see what we came for: the Cathedral of Burgos, La Santa Iglesía Catedral Basílica Metropolitana de Santa María. We walked out of the church and looked up. It was stupendous. The cathedral of Burgos is one of Spain’s lesser known treasures, at least to outsiders. Even greater than the Cathedral of

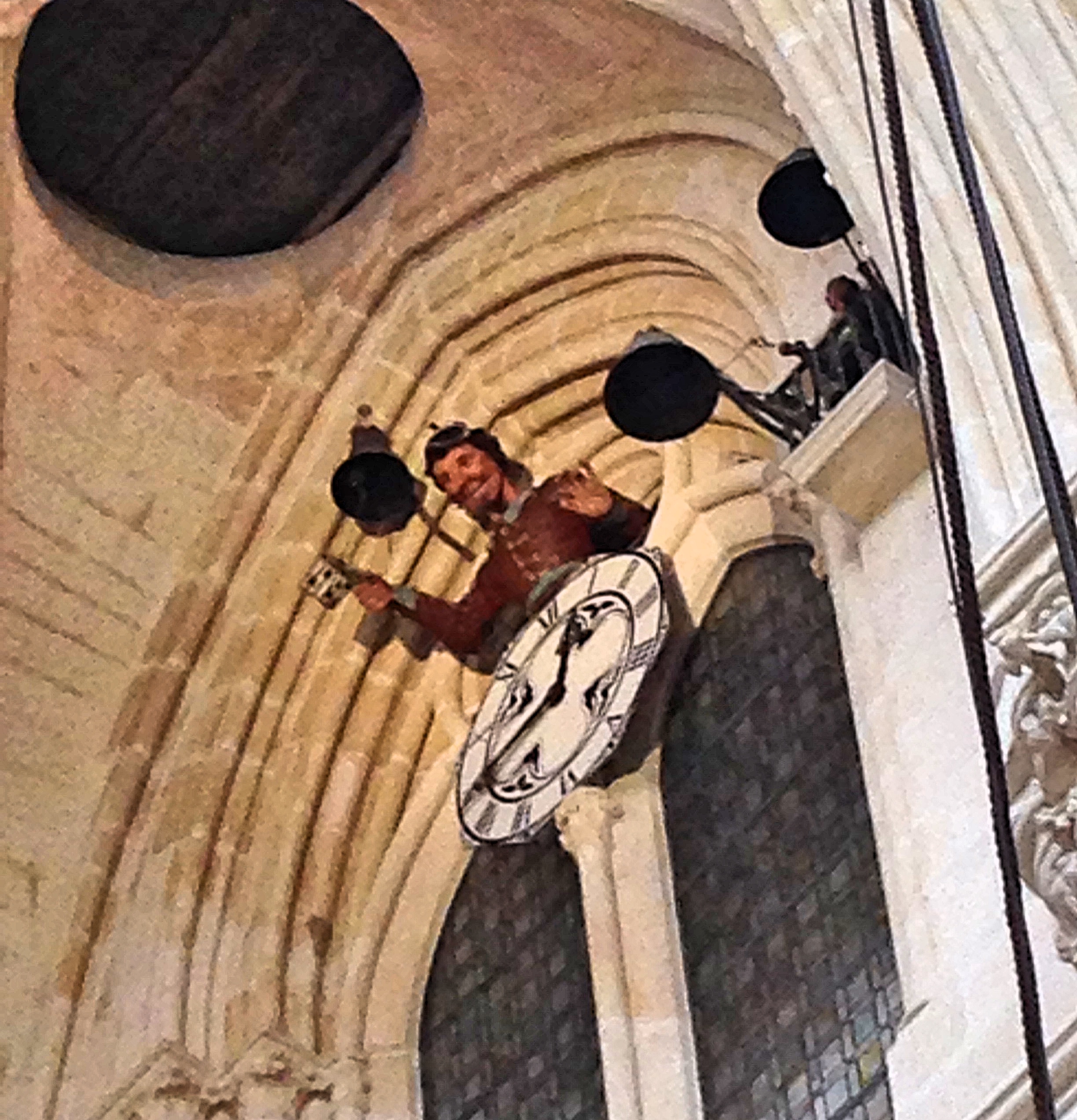

Then there was the central cupola. This was unlike any I had ever seen before. Instead of a large dome crowning the building, it was filled with small windows in an intricate pattern; standing underneath and looking up, it looks like heaven itself is opening up. The audioguide explained how it was created, but I don’t remember now, and even at the time I couldn’t believe it. Hanging from so high a place and looking as delicate as paper ribbons, it is impossible to believe it was made from stone. The credit for this lovely work goes to Juan de Vallejos, an otherwise obscure and unknown figure.

Then there was the central cupola. This was unlike any I had ever seen before. Instead of a large dome crowning the building, it was filled with small windows in an intricate pattern; standing underneath and looking up, it looks like heaven itself is opening up. The audioguide explained how it was created, but I don’t remember now, and even at the time I couldn’t believe it. Hanging from so high a place and looking as delicate as paper ribbons, it is impossible to believe it was made from stone. The credit for this lovely work goes to Juan de Vallejos, an otherwise obscure and unknown figure.