When you live in Europe, you notice that certain destinations come up in conversation with surprising frequency. Porto, Budapest, and Normandy are among those which are highly-praised among the well-traveled. Edinburg is another. So although I had no special reason to go—I had not even found an especially cheap flight—I decided that I would use my February vacation to take a little trip up north and see what all the fuss was about.

The plane broke through the gray clouds and touched down in Scotland on a cold, drizzly morning. I found the bus indicated by my Airbnb host and got on the top floor. The double-decker bus afforded me a commanding view of a not-very-exhilarating urban landscape as we traveled from the airport to the suburb where I was to stay. Though there really was nothing interesting to see, the combination of the dreary skies and the (in my eyes) quaint domestic architecture made a powerful contrast with the usual Spanish scenes of sun and walled-in houses.

Soon enough, I was at my destination. It was a rather odd Airbnb experience. My host told me that she had been repeatedly trying to contact me, only to realize that she was thinking of another guest (she managed various properties). Then, I was told, among other things, that the shower was set to the absolute perfect temperature and ought not be changed; also, she insisted that Scotland was just as humid as Florida, so that I ought to leave my window open for a certain amount of time every day to prevent mold. (Unless I am mistaken, the amount of moisture that air can hold is dependent on its temperature, so that cold Scottish breeze can’t hold nearly as much humidity as the scorching soup that is Florida’s atmosphere.) But this sort of thing is par for the course when staying in somebody else’s place. At least it was cheap.

With my bag dropped off, I caught the bus to the city center. I really appreciated the double-decker bus now, as it allowed me a wonderful way to enjoy Edinburgh’s Old Town. But by the time I stepped onto the cobblestone street, I was tired, thirsty, and extremely hungry. The daylight was fading now, and I desperately wanted dinner. This did not put me in the best mood to appreciate the lovely city which now opened up before me. Yet I was sentient enough to notice that the architecture formed a kind of coherent whole, all of the buildings made of the same grayish-brown stone, and constructed in the same heavy style, which seemed somehow suited for this clime.

I wandered up the venerable streets feeling rather sorry for myself, as I peered into window after window to see family and friends having dinner. I did not have the heart or the stomach to walk into a restaurant by myself and eat at a lonely table. I wanted something fast and anonymous, and my prayers were answered when I discovered a quiet kebab shop. I sat down at one of few chairs and, within minutes, my meal was ready. Better than any kebab I had in Spain, and this was not even a well-known spot. And as I ate, I reflected on the stark difference between what I had just observed of Scottish eating culture, huddled up inside, and that of Spain—where patios are overflowing onto every sidewalk. Of course, the weather is the explanation, though I also found it curious that nobody else was in this kebab shop on a Friday night. In Spain, it would have been full to the brim with drinkers.

It was, by now, too late to see any attractions. But it was not too late to enjoy a drink. For this, one of my friends had suggested the famous pub, Sandy’s Bell. Though I was somewhat buoyed by the food, I still felt nervous when I looked through the cloudy windows to see a bar filled with a rowdy crowd. But after pacing back and forth on the frigid street, I mustered enough courage to barge in. The barman immediately asked me for a drink and, like an idiot, I just said “beer.” (In Spain one often just orders “cerveza” and you’re given the only beer on tap.) He wasn’t satisfied with that, and asked me to choose a beer, and I scarcely helped matters when I said “an ale.” One of the regulars at the bar—an older man—took matters into his own hands and said “Try this!” while holding his own drink up to my lips. Too surprised to refuse, I drank a gulp and said, “That one!” The barman returned shortly with a pint of the dark ale.

My troubles were hardly over. The place was packed and every chair and barstool was occupied. I found a corner of the wall I could lean on and sipped my beer rather awkwardly, trying not to be noticed. This was my first Scottish pub experience, and somehow I found it very intimidating. I tried to slow down and enjoy the beer (which was quite good), but I found myself drinking faster and faster, as a part of me was eager to leave. When I realized that I was failing to enjoy the pub, I got rather down on myself—all these years of traveling had not cured me of feeling like a misplaced high school student—but slowly resolved to cut my losses.

Just as I had taken the last sip of beer and I was ready to pay and head out, a man got up to leave from the bar and, like an angel from heaven, offered me his seat. (I really must have looked conspicuously uncomfortable.) I thanked him from the bottom of my heart and got ready for another beer, this time from the commanding position of the bar. A drink sitting down is incomparably better than one standing up, and I felt quickly at ease. The experience was made even better with the purchase of a bag of crisps (salt and vinegar, my favorite flavor, which is rarely available in Spain), which persuaded me that I ought to have a third beer.

Time slowly ticked by. Eventually I remembered that the bar is famous for its live music. I asked a nice young fellow to my left, and he told me that it started at nine. I looked at my watch: about 45 minutes to go, and no beer left. My better judgment told me that I should just stop and come back another night; but my tempting demons—rather convincing, usually—told me that I ought to just tough it out until I heard some music. The decision was instantly made when I spotted a bottle of Laphroaig on an upper shelf. This is my dad’s favorite type of whiskey, and I felt duty-bound as a son to have a glass in his honor. This was ordered, and I could have sworn that I could feel a wave of respect pass over my fellow patrons.

Laphroaig is, you see, not an especially popular single-malt scotch. A single taste will let you know why. Coming from the island of Islay (pronounced “eye-luh”), this scotch is normally described by whisky enthusiasts as “peaty,” though the first words that come to mind of most ordinary people are considerably less kind. It tastes, to me, how I imagine a strong iodine solution would taste (though admittedly I have never tasted iodine). In other words, Laphroaig is harsh—almost chemically harsh. And yet, strangely, the taste grows on you. If you can get past your initial revulsion you will find it has a sort of complex smokiness beneath the initial shocking acrimoniousness. In short, I actually managed to enjoy my glass of Laphroaig.

And luckily for me, the music began right as I was finished. It was a small group of three people, two on guitars and one on violin, playing lively tunes. I took it in for a while, and then caught the bus back to my Airbnb. I had a big day ahead.

I will begin by mentioning the things I did not decide to see. Perhaps most notably, I did not visit Edinburgh Castle. This is probably the most famous and popular monument in the city—perhaps in all of Scotland—and, even from the outside, you can see why. It is an impressive and imposing fortress which towers over the city. However, from what I read about the castle, there was nothing on the inside which I thought merited the steep entry fee. But I did enjoy the sculptures of Scottish heroes Robert the Bruce and William Wallace that adorned the entryway.

Next on my list of negative tourism is the Holyrood Palace. This palace is actually connected to the castle with a broad avenue known as the Royal Mile (though it is really a little longer than a mile). Holyrood is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland, still used whenever the king or queen is in town. The rest of the year, it is open to tourism. I actually think that Holyrood is likely a rewarding place to visit, but palaces tend to put me in a bad mood.

But I did enjoy seeing the ruins of Holyrood Abbey behind the palace. While I assumed that it had been gutted in a fire, the story of its destruction is quite a bit more interesting. The abbey played an important role in Scottish history for several centuries after its construction in the 12th century. But when its old timber roofs were replaced by stone vaults seven-hundred years later, this proved to be the end of the old church. Its walls could not support the added weight and the roof eventually collapsed. It does make a fine ruin, though.

Another major attraction that I did not visit was Her Majesty’s Yacht, Britannia. As its name suggests, this yacht was used by the British royalty from 1954 to 1997, and is now a kind of museum showcasing royal pomp and luxury. Needless to say, this would have put me in a bad mood, too.

The last attraction I missed was Mary King’s Close. Now, a “close” is just another term for an alley, and there are a lot of alleys in Edinburgh. The historic center used to be enclosed by a wall, requiring high density, and so these closes are highly claustrophobic spaces—hemmed in by neighboring buildings. This particular close (named after a merchant) was, well, closed as neighboring construction both partially destroyed and buried the little alleyway. Nowadays the abandoned close has something of a reputation among ghost hunters and other seekers after the paranormal. But tourists enjoy the tours about daily life in 17th-century Edinburgh. Perhaps I ought to have gone to this one.

So where did I go? My first visit was to the National Museum of Scotland. This is an enormous museum with a collection of virtually anything you might imagine. And best of all, it is free to visit. The central hall is immediately impressive—a large area, full of light, modeled on the original Crystal Palace. There, I was immediately attracted by the skull of a sperm whale (“Moby”) who had washed up on Scottish shores and who, despite rescue attempts, unfortunately perished. Moby was not an especially large male (indeed, slightly below average), but even so, his skull alone is longer than two tall men lying end-to-end.

As I said, the museum has a vast and varied collection. There is an exhibit on space, animals, geography, fashion, Ancient Egypt… But I figured that, if I was in Scotland, I ought to visit the Scottish History wing. This is housed in a separate and rather futuristic building, and it makes for an excellent visit. You are led, chronologically, from the stone age on the ground floor to the industrial revolution at the top. Though Scotland is a small and rather remote country, this exhibit encapsulates all of the glory and interest of its history. As I traveled from a medieval greatsword to James Watt’s steam locomotive, I found myself almost awed by how much had transpired in this soggy northern country.

Right next to the museum is another popular attraction: Greyfriars Kirkyard, a historical cemetery. But before you enter, you might notice the small metal statue of a terrier with a polished nose. This is Bobby, a semi-legendary dog who—according to the story—spent 14 years guarding the grave of his deceased owner, John Gray. The story is understandably quite popular, and Bobby (or his statue) is undeniably cute. But I have to admit that I feel skeptical. Not that I deny the nobility and loyalty of our canine friends, but the story does seem too perfectly calculated to attract tourists. And there are many reasons (free food?) that a dog might be found in a graveyard.

Well, whether or not the Bobby story is perfectly accurate, Greyfriars is worth visiting. I must admit that my knowledge of Scottish history is so spotty that I did not recognize a single name. Yet the grandeur of the tombs is enough to impress upon the visitor the importance of this burying ground. While I strolled around, I noticed two Americans who seemed to be walking with determined step to a particular grave. Thinking that they must know something I didn’t, I followed them as they made their way to the edge of the graveyard. There, I was disappointed to find that they were visiting the grave of a man named Tom Riddle. Now, I have no idea who this man really was, and I am sure my American guides did not either. They were visiting because this name was used by J.K. Rowling as an alias for Voldemort. (Indeed, I think there is quite a lot of Harry Potter tourism to Edinburgh.)

Though I did not know this story at the time, this is the perfect moment to mention one of the more macabre episodes in Edinburgh’s history. There was a time in Scottish history when the medical demand for human cadavers—which doctors used in their lectures—far outpaced the supply, mainly because of strict laws regulating which bodies could be used for such a purpose (paupers and prisoners, mainly). This led to the grotesque practice of “body snatching,” in which grave robbers would dig up the recently buried and sell them to a doctor for a handsome profit. Indeed, this was such a problem that several anti-robbery devices were developed, such as the mortsafe, which is basically a cage placed over the body. (You can see examples of these in Greyfriars.)

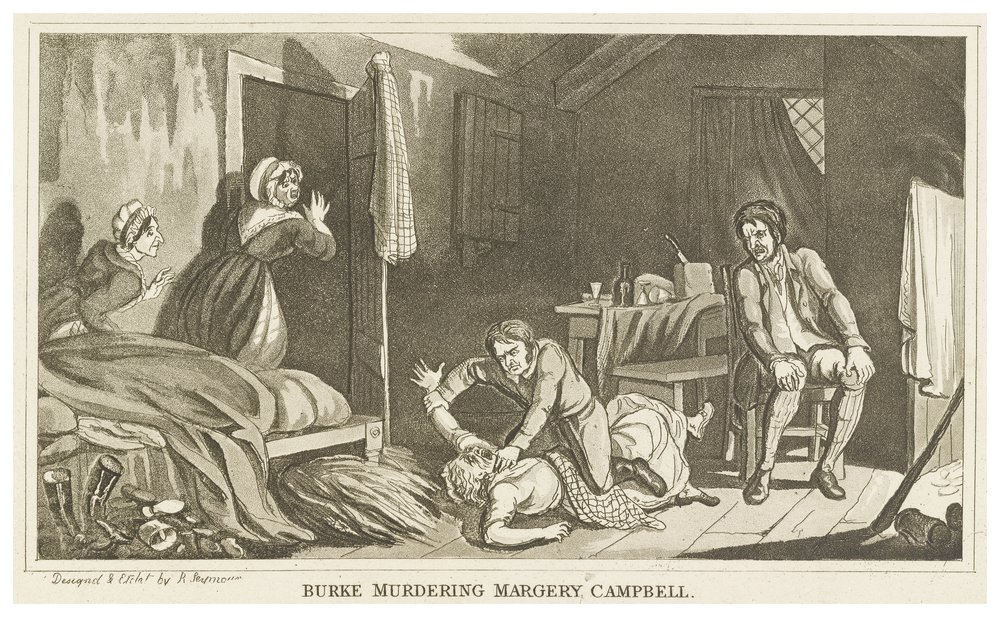

But in 1828, two men decided to take this practice one step further, and began murdering people in order to sell their bodies. The men had a very simple system: get a person very drunk, and then smother them to death by laying on top of the victim. After sixteen such murders, they were discovered. One of them, Hare, was inexplicably given a light sentence, while the other, Burke, was hanged for his crimes. With poetic justice, Burke’s body was then dissected before a group of medical students. His skeleton is still on display at Surgeon’s Hall in Edinburgh (I wish I had gone!), as well as—and this strikes me as a tad overboard—a notebook bound with Burke’s skin.

While I am on this morbid topic, I should mention two other tombs I visited during my time in Edinburgh. One was of the great economist Adam Smith, who is buried in the graveyard of Canongate Kirk. The grave is neither big nor particularly elaborate, but its inscription gets right to the point: “Here are deposited the remains of Adam Smith, author of the Theory of Moral Sentiments and the Wealth of Nations.” Nothing more need be said, as those two works will last longer than any tombstone. Next I visited the tomb of the other great pillar of the Scottish Enlightenment, David Hume. This is in Old Calton Cemetery, which is located on Calton Hill, one of the high points of the city. His tomb is slightly more monumental, consisting of a kind of hollow tower, but there is no memorable inscription. Yet merely being close to the mortal remains of this most skeptical of philosophers was a thrill (though he would likely say I was irrational).

Curiously, right next to this tomb is a statue of one of my countrymen, Abraham Lincoln. He stands over a monument to the Scottish American soldiers who died in the American Civil War. The Scottish are an international bunch.

Very close to Hume’s final resting place, right at the crest of the hill, is a park. In addition to providing excellent views over the city, there are a few curiosities to be found here. The most obvious, perhaps, is the Nelson Monument—an enormous tower, dedicated to the memory of the admiral who helped defeat Napoleon (and, thus, a very British memorial).

But I much preferred the other massive stone construction, the National Monument of Scotland. This was intended to be a glorious monument to the Scottish soldiers who died during the Napoleonic wars, modeled after the Parthenon in Athens. (This idea, by the way, was owed to the notorious Earl of Elgin, who stole the Parthenon frieze from Greece and brought it to the British Museum, where it remains to this day.) The final result, however, is comic and slightly pathetic. The campaign ran out of funds when just the portico had been completed, and it has remained that way ever since. Now it is just a collection of massive columns over a base—columns holding up nothing, a glorious doorway leading to nowhere. But it is great fun to climb on.

Even more fun to climb was Arthur’s Seat. This is a hill, formed by an ancient volcano, which looms over the city, and which is to Edinburgh what Central Park is to New York. Nobody quite knows why it is called Arthur’s Seat, as it seems highly unlikely that King Arthur—if he even existed—built Camelot here. Thinking that I ought to maximize my time in Edinburgh, I climbed the hill in a mad rush and got to the top in less than an hour. (What are vacations for, if not to anxiously hurry through?) Once there, I got a taste of the famous Scottish wind—or, as they might say, it was a wee bit blowy. The view of the city and the sea beyond was wonderful. The landscape was impressively rugged and wild. Somehow, for a park right next to the capital of Scotland, Arthur’s Seat transports you instantly to the middle of nowhere.

I should mention that observation of the geology of Arthur’s Seat helped James Hutton develop his scientific ideas. And this is no small thing, as Hutton is known as the “Father of Modern Geology,” whose work basically initiated the modern discipline. This influential Scot is buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard.

Now, this does it for my first complete day in Edinburgh, which was long and exhausting. However, as the rest of my sightseeing was done in snatches around a daytrip (mentioned below) and before my flight back, I will mention the remaining sights here without attempting a narrative.

If you walk around Edinburgh, you will undoubtedly notice an infinity of shops selling scarfs and sweaters with what we call, in the US, a plaid design. In Scotland, this is a tartan, and they are often organized according to family names, or “clans.” I was rather excited to find a scarf with the design of my own “clan,” the Johnstons (through my mother’s mother). However, I really did not need a scarf and so decided not to buy one. I am glad I didn’t, as it turns out that this tartan-clan typology is a prime example of what the historian Eric Hobsbawn called an “invented tradition”—as it only goes back to the 19th century and was an intentional way of shaping perceptions of Scottish history. In other words, it is not true that “clans” were proudly displaying their colors back when William Wallace was slicing through Englishmen. Oh well.

If you are in the center of the city, it is certainly worth your while to step into St. Giles’ Cathedral. This is the mother church of Scotland, where John Knox—the Scottish Martin Luther—acted as minister. Now, I must say that I am far too ignorant to give you any more information about this church, so I will only add that it is both beautiful and central to Scottish history. For example, proudly on display is the National Covenant, a document signed in opposition to the king’s attempt to meddle with Scottish religion. If that isn’t a symbol of Scottish independence, then I don’t know what is.

Nearby is a monument to David Hume. The handsome philosopher lounges in a chair, dressed in a toga, and holding a large book. When I visited, however, he was also wearing a Ukrainian flag. This was February 28, 2022, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine had begun just four days earlier. Most commentators had assumed that the battle would be over within the week, perhaps in just three days. So it is stunning to me that, as I sit here over a year later, the war is showing no signs of stopping. I am sure that Hume would have something incisive to say about the folly of mankind in this regard.

There are, of course, monuments and statues all over the capital of Scotland (I’ve already mentioned many), but I think that the grandest is easily that of Walter Scott. It is something of a monstrosity: a neo-gothic spire that ascends 200 feet (60 meters) into the air. This stone needle is covered with statues: 64 characters from Scott’s novels, 8 kneeling druids, and 16 busts of other Scottish poets and writers. Walter Scott and his dog, life sized, sit in the center of this stone carbuncle, almost comically small by comparison. As you may well imagine, an enormous number of stonemasons had to be recruited to put this together; and apparently the hewing came at a steep human cost, as many masons were fatally inflicted with silico-tuberculosis from breathing in the stone dust.

Considering Scott’s fairly modest place in the Western literary canon nowadays, this huge effort seems disproportionate to say the least. But during his lifetime, he was among the most famous and influential authors in the world. As it happens, when I visited, I had just finished reading Ivanhoe; and I think that the monument’s faux-medieval grandeur is quite in keeping with Scott’s style.

I cannot wrap up my time in the Scottish capital without mentioning some Scottish food. Now, when I was younger, my friends and I used to joke (for some reason) about haggis, treating it as an epitome of a disgusting dish. Certainly a description of the food—minced sheep innards cooked in its stomach—does not sound particularly appetizing. But when I ordered a plate of haggis with “neeps and tatties” (rutabaga and mashed potatoes) at the appropriately-named Haggis Box, I found that it was absolutely inoffensive—not only that, but tasty. The meat is minced with onions, oatmeal, and a generous amount of black pepper, and to me was quite reminiscent of Spanish morcilla (blood sausage) in both flavor and texture. In any case, when you stop to consider what goes into an ordinary sausage, then haggis ceases to appear exotic.

Another Scottish classic is the Full Scottish Breakfast. This is rather similar to the English Breakfast, though it is even richer and heavier. Standard components include: bacon, sausage, haggis, eggs, toast, fried tomatoes, mushrooms, baked beans, and potato scones. I had one of these at the Southern Cross Café before my flight back to Madrid, and did not have to eat anything the rest of the day. A wonderful experience.

This pretty well does it for my time in the city of Edinburgh. But I cannot leave off writing without an overview of the whiskey—or, as the Scottish write it, “whisky.” For this, I went to the Scotch Whisky Experience, which is located quite near Edinburgh Castle. It is certainly a touristy place, though I quickly found that it was a worthy visit.

The first part consists of a silly “ride” on a whiskey barrel, during which an animated Scottish ghost (“animated” in both senses) explains the process of making this distilled spirit. In short, this consists of fermenting malted barley, distilling it until the alcohol content is at least 40%, and then aging the result in an oak barrel. The second part was a kind of virtual tour of the Scottish whisky regions, which are: Upland, Lowland, Speyside, Campbeltown, and Islay. We were each given a scratch-off with the distinct aromas of each whisky type—and, sure enough, the Islay sample smelled like Laphroiag.

Along with these single malt types (which must be made from malted barley), there is blended whisky, which is usually both cheaper and milder, and thus comprises most of the market. Blended whisky is made from a mixture of grain alcohol (usually corn) with a bit of single-malt. The grain alcohol is fairly neutral in flavor, so any personality is derived from the single malt that is added.

I was then given a tasting of four single-malt scotches, and thought the Islay whisky was the most interesting (if not necessarily the most drinkable). Indeed, I found the “Experience” to be surprisingly rewarding. Perhaps this is just a romantic notion, but I felt as though Scotland itself was palpable—indeed, tasteable—in each glass. The harsh and smoky flavors somehow called to mind the soggy, grassy, and rocky landscape that I had glimpsed on Arthur’s Seat. Just as it is difficult to imagine such a robust and unforgiving liquor being cultivated in sunny Spain, so is it equally impossible for the rugged landscape of Scotland to yield up anything gentler than this spirit.

During my time writing book reviews on Goodreads, I have “met” many interesting people. One of these is a woman named Karen, who is from Scotland but who has lived in Germany most of her adult life. By chance, she was in Scotland during my visit, and so we agreed to actually, physically meet, as she kindly offered to show me a few sites near Edinburgh.

The drive itself was slightly disorienting, as Karen had brought over her German car but we were driving on the opposite side of the road. Everything was as in a mirror (you pass on the right), but thankfully, Karen did not seem flummoxed. I began to reflect that, even while walking on a sidewalk, an American or a Spaniard will naturally keep to the right side. Do British people naturally keep to the left on the pavement? Somebody must study this.

Our first stop was the Falkirk Wheel. This is a rather odd contraption, designed to unite two canals built at different levels. The Forth and Clyde Canal was opened in 1790, and the Union Canal 32 years later, in 1820. Together they provided a water route between the two major cities of Scotland, Glasgow and Edinburgh; but the problem was that the canals are built at different heights, with the Union Canal 115 feet (35 meters) higher than the Forth and Clyde. This height difference was originally overcome with a series of eleven locks—which is the standard solution. But locks are also expensive and slow, as they take a long time to fill and empty, and require a lot of water and energy for pumps. In any case, the age of canals was soon superseded by the age of the railway, and the canals fell into disuse. Eventually the locks became inoperable and were taken apart, and the canals became rather useless watery ditches.

But as the new millennium approached, the authorities decided that this waterway should be reopened—if not for commercial, at least for symbolic reasons. This beautiful piece of infrastructure was the result. The wheel consists of two troughs of water balanced around a central spoke. By just slightly adjusting the amount of water in each trough, gravity can be used to help turn the wheel and take ships up and down. As such, it is both faster and more efficient than a traditional canal lock, though I am not sure if it could work on a larger scale (such as on the Panama Canal). It is also simply a sleek design.

Karen and I took the canal “cruise,” though to call it a cruise is like calling a walk in the park a “safari.” This is not to say that it was uninteresting. About twenty people got into a boat and we were (very slowly) lifted up to the Union Canal, while a guide explained some of the history of the canal.

I was especially entertained because the guide had a wonderful, classic Scottish accent. Though every word he spoke was recognizable, it was as if he had put a different vowel between the same consonants. (Sance ya can rad a santance wath all the vawals changed, ya can andarstand wan taa.) While on the subject, it is worth noting that Scottish people have a habit of pronouncing names in surprising ways. For example, though Edinburgh seems obviously meant to be pronounced “eh-din-burg,” the Scottish say “eh-din-bruh.” There are also a few characteristic bits of Scottish English I noticed. “Kirk,” for example, is a local word for “church; and on one traffic sign, the reader was instructed not to park “outwith the line”—the preposition meaning “outside of.” A useful word, that.

Our next stop was, for me, wholly unexpected. Karen informed me that we were going to see a big sculpture, but when I laid eyes on The Kelpies I was stunned by their scale. This is a work by Andy Scott and was completed just ten years ago, in 2013. Two horse’s heads—98 feet, or 30 meters, high—emerge from the ground near a section of the Forth and Clyde Canal. A “kelpie” is, apparently, a kind of water spirit that takes the form of a horse. But Scott has stated that the statue was meant more as an homage to the work horses who played an important role in Scottish history, not least by pulling barges on the canals. The sculptures are made of steel and, for something so large, are remarkably dynamic and lifelike. I think it is a wonderful work of public art.

After that, we headed to a little town called Culross (pronounced “coo-riss,” for some reason). This is a little town across the bay from Edinburgh. Our first order of business was lunch, for which we found a serviceable—if rather slow—taco truck. Then we ambled into town, where we found that there was a little market set up. I took the liberty of buying some fudge and coffee, and had yet another experience of Scottish friendliness. Everyone there was talkative and pleasant. Karen and I walked around the town for a bit, enjoying the lovely village architecture and peeking into the abbey, which was closed when we were there.

Our final stop was in the town of North Queensferry, in order to see the bridges which span the Firth of Forth. “Firth” is yet another example of Scottish English; it means an estuary. The Firth of Forth is, as you may expect, on the river Forth, which reaches the ocean near Edinburgh. At this particular junction in the river, three huge bridges span the division.

We parked the car, ascended a staircase, and soon found ourselves on one of these bridges—the Forth Road Bridge. This is perhaps the least visually interesting of the bridges, but it is the only one open to pedestrian traffic. Indeed, there is little else on the bridge. Opened in 1964, it was in service until 2017, when it was replaced by the adjacent Queensferry Crossing Bridge. Since that time, it has only been open to pedestrians, buses, and taxis. Karen and I thus had the bridge almost all to ourselves. I found it to be a wonderful idea, and now I wish the same was done with the old Tappan Zee Bridge, in New York, which was demolished to make way for the new one. (To be fair, the new one does have a pedestrian walkway.)

The Queensferry Crossing Bridge is an attractive piece of infrastructure. But the real star is the original Forth Bridge. Completed in 1890, this railway bridge is a monument to Scottish engineering. Its design was innovative and was especially noteworthy in using steel—a relatively new material for large constructions at the time. The pictures of the bridge do not do it justice. You need to see it up close to get a sense of its massive scale.

Apparently, the bridge was built so robustly because of an earlier disaster. In 1879, the Tay Bridge (spanning the nearby Firth of Tay) collapsed while a train was passing over, killing everybody onboard. This had the effect of scrapping the original plans for the Forth Bridge, as it was designed by the same architect, Thomas Bouch. (Bouch died less than a year after the disaster, his reputation in ruins.) This tragedy is also notable for being the subject of one of the worst poems ever written in English, by the iconic bad poet, William McGonagall. His poem begins:

Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay!

Alas! I am very sorry to say

That ninety lives have been taken away

On the last Sabbath day of 1879

Which will be remembered for a very long time.

(He is buried in Greyfriars, if you would like to pay your respects.)

After we finished admiring the bridges, Karen kindly dropped me back off in Edinburgh. My time there, I have already described, so I will bring this long post to a close. As I hope I have conveyed, I had a wonderful time in the Scottish capital. It is a beautiful and fascinating city, and I hope to return one day, and to see even more of Scotland.