This is part of a series on New York City museums. For the other posts, see below:

- The Frick

- The Morgan

- The MoMA

- The Cloisters

- The Museum of Natural History

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In a city full of famous art museums, the Metropolitan is undoubtedly the queen. The institution is a behemoth. With a collection containing millions of objects—objects which come from every corner of the world, from ancient times to the present day—the museum has nary a rival in the world for range. And the objects comprising this encyclopedic collection are, inevitably, of the finest quality that money can buy. By now I have seen enough of the great European museums to say confidently that the Met can compete with any of them.

The museum was conceived as a kind of sister institution to the American Museum of Natural History. It was an age when the rich and educated sought to “civilize” the less privileged. Both museums are located near Central Park, a place which itself was designed as a civilizing project—a kind of pastoral refuge from the ills of city life, where the people could learn to appreciate more refined recreational activities: Sunday strolls, picnics, birdwatching, and so on. The Museum of Natural History would bring the light of knowledge to the uneducated, while the Met would show the unsophisticated the value of high art.

The museum’s founders were embarking on a pathbreaking project. There were already plenty of examples of great European museums to learn from. But what would an American art museum be like? When the museum opened in 1872, its collection was modest. Indeed, many of the works it displayed were either prints or reproductions of famous European works. Yet this quickly changed. New York was emerging as the financial capital of the world. Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and J.P. Morgan were among the city’s residents. Since Europe was still considered the cultural epicenter of the West, these newly-minted super-rich naturally spent their piles of gold in buying up as much European artwork as they could.

The Metropolitan benefited immensely from this confluence of money and ostentatious display. Not only did the museum itself have the budget to purchase high-quality works, but it also increased its collection from gifts and bequests. After all, donating beautiful art to a public museum is a good way to demonstrate wealth and civic-mindedness at once. We ought not to criticize, however. There are times when the vanities of the world manage to produce genuine treasures. And the Met is certainly such a treasure.

At present, the museum’s holdings are so vast and varied that no single person, however knowledgeable, could hope to do justice to it all. It would take a team of professional art historians working for years on end to complete even a basic catalogue of the museum’s works, much less an appreciation along aesthetic grounds. And I am no art historian. So in this post I hope only to give you a superficial tour through this enormous institution. (Much of the information and many of the images come from the Met’s website, which is quite well-made. The people at the museum have done the world a service by publishing high-quality public domain images of their collection.)

We begin at the entrance on Fifth Avenue. The museum is difficult to miss. The building stretches out along several city blocks. Fountains shoot and sprinkle outside, and the sidewalk is always thick with crowds. The building is neoclassical in form, its façade a kind of pale white decorated in a pseudo-Roman style. The steps leading up to the main entrance, lined with imposing double columns, are one of the most iconic spots in New York. There are always food stands parked right below these steps, and usually a street performer—a dancing saxophonist, perhaps—plays for the amusement of those sitting on the steps.

We enter the building, and are faced with a choice: right or left. There are ticket stands on either side. To the left there is a graceful Greek statue of woman, and to the right a stiff Egyptian man seated on a throne. These statues are informative, since the respective galleries for these cultures are located in these directions. For the purpose of getting a ticket, the choice is immaterial: the lines on either side are normally about the same, and usually move pretty quickly.

Now, there was recently a significant change in the museum’s admissions policy. For the past few decades, visitors could pay any amount they liked. Just last year, however, the museum changed its recommended prices to mandatory payments—for everyone except residents of New York State, that is. (Lucky for me, I am still a resident.) Another change, by the way, was the switch from using metal clips to using stickers to identify visitors. I am sure that the Metropolitan has increased its budget by making these changes. But I admit I miss the old, pay-as-you-wish, metal clip Metropolitan. A man from China could pay a dollar, and leave with a nice little keepsake from his visit. I still have some of the old clips in my room.

Anyways, let us now enter the museum proper. I like to begin with the Egyptian section, not just because it is near the entrance, but also because it represents the chronological beginning of the museum’s collection. Here we can ground ourselves in one of the world’s oldest civilizations before we examine anything else.

The Egyptian section is massive and labyrinthine. Unlike the other departments of the museum, the Egyptian department displays everything in its collection—almost 30,000 objects. To make room for all of this, the halls double around one another, making it sometimes confusing to navigate the collection. But it is a worthwhile use of one’s time to get lost in the art. If you proceed carefully through the department, you can take a very satisfying chronological journey: beginning near the entrance, in prehistoric Egypt, and ending up in the same spot, having gone through the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms, and finishing in the Roman era.

Now, I love this department, because it has everything. Walking through it, the visitor gets a very complete picture of life in this ancient civilization. Of course there are sarcophagi and mummies, along with amulets, jewelry, and ceramics. Among the most famous of the smaller pieces in the museum is William the Hippopotamus, a beautiful figurine made of faience, which is a ceramic type specific to Egypt. It has a radiant blue color that is delightful to look at.

The museum also has a wealth of larger statues, ranging from the size of a child to the size of a giant. For me, the most beautiful of these is a statue of the pharaoh Hatshepsut. As you may know, Hatshepsut was the only woman to officially become the pharaoh. This presented a challenge for Egyptian artists. The art of Ancient Egypt is distinguished for its astonishing conservatism, preserving the same stylistic features through centuries. A single glance is all we need to know that something is Egyptian. But portraying a woman required innovation, and the artists rose to the challenge. Rather than making her appear masculine, as they did in other works, in this seated statue Hatshepsut appears both feminine and even feline. There is a smooth grace and delicacy to the sculpture which is rare in the usually rigid forms of Egyptian art, and I find it enchanting.

Though not, perhaps, especially beautiful, some of the most illuminating artifacts on displays are sets of models. Made around 1900 BCE, the models were found in the 1930s in a tomb in the Memphite region of Egypt. They show us rare scenes of daily life in Egypt. We can see several boats travelling along the Nile, one of them transporting a mummy, another for hunting. There are also models of more cotidian scenes: a granary, a garden, a house. These models are wonderful little things, since it is as if they were made by the Egyptians for a museum exhibit about Egypt. It is difficult to identify with the people who sculpted enormous statues of god kings, but very easy to see oneself gardening.

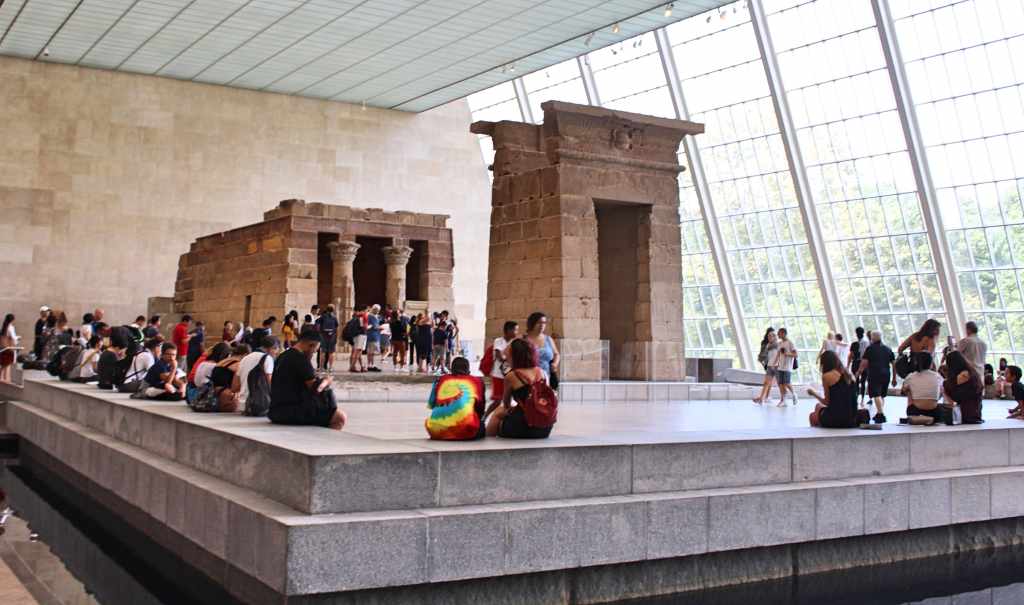

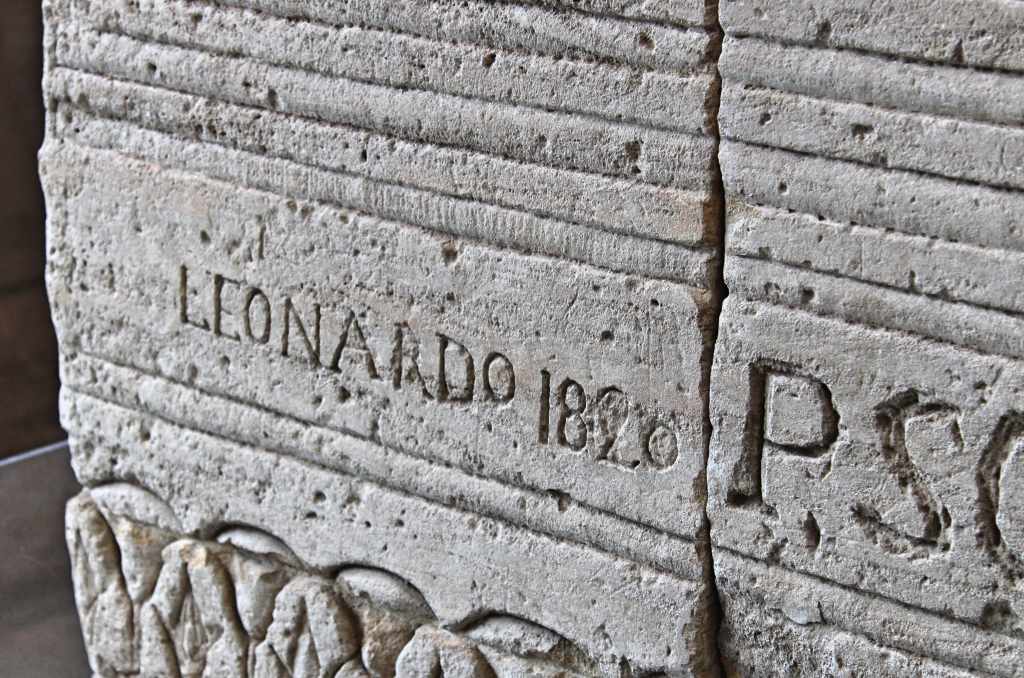

The centerpiece of the collection is the Temple of Dendur. The Met actually has large sections of several temples in its collection, from different periods of Egypt’s history, but this is the only complete, free-standing temple in the museum. It is in the center of a large room, surrounded by a little water moat where visitors like to throw coins. Statues of crocodiles and lion-headed gods surround the space. The temple itself is of a fairly modest size, and is from the end of Egyptian civilization. It was built after the conquest of Egypt by the Romans, and commissioned by Augustus himself. While the temple is a lovely work of architecture, what most stuck in my memory were the many graffiti carved into the walls.

When you complete your circuit through the Egyptian section, you will be where you began, right by the entrance. From there, I like to go across the hall and then into the section on Ancient Greece. This part of the museum looks very different. Whereas the Egyptian section is twisting and jam-packed, the Greek section is open and clear. The visitor enters a large hall with a vaulted roof. Free-standing statues are scattered through the space, while friezes line the walls. For any lovers of classical art—with its flowing robes, idealized forms, and restrained emotion—there are dozens of works to admire. While I greatly enjoy the statues, I find myself even more interested in the friezes. Some of these come from Athenian tombs, such as a touching portrayal of a little girl cradling a dove.

The collection contains many excellent examples of art from Classical Athens—art that we readily identify as quintessentially Greek. Besides the statues and freizes, there are many examples of Greek vase art. But the collection also contains works that do not fit this description. Among these are the many sculptures from pre-Classical Greece, which to our eyes can seem more Egyptian than anything. The museum has an excellent example of one of these kouroi: A young man, standing with one foot extended forward. I like the work, since it is an interesting example of a midpoint between Egyptian stylization and Greek realism. The young man is manifestly unreal, and yet the musculature in his limbs and torso is well done. An even older work—from around 750 BCE—is a terracotta vase. Its decoration is very much unlike the red, white, and black images of gods and heroes we normally associate with Greece. Rather, it is covered in a thick pattern of geometrical shapes and tiny like stick-like figures. I quite like it.

The collection of Roman art is perhaps even better than that devoted to Greece. There are several excellent busts of Roman Emperors. I have a long, personal attachment to a bust of Marcus Aurelius in the collection, which to me is the perfect image of a philosopher—calm, wise, detached. I use it as my own symbol now. A much more amusing work is a statue of Trebonianus Gallus. It is a rare example in the Met of art gone wrong. Clearly, whoever made it was not a master. The whole figure is awkward, with a bulging stomach and a head that is manifestly too small. Maybe Rome was not doing so well in the year 250 CE, when it was made.

Statues, being made of metal or rock, naturally preserve very well. But painting is another story. Even though the Greeks had a developed tradition of painting, nothing has survived the ravages of time. That is not the case for Rome, from which we have many well-preserved wall paintings. The Met has an entire room, the bedroom of P. Fannius Synistor, which was buried in the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE. The art on the walls is really wonderful, showing several architectural and natural scenes. It shows us how the Romans gave a realistic impression of space without using the technique of perspective. Having seen my fair share of Roman wall frescoes and mosaic floors, I must say that they had wonderful taste in interior decoration.

As you can see from this example and the Egyptian temple, the Met is big on re-creating interiors. This is a theme throughout the whole institution, and one of the Met’s most distinguishing features: The visitor is allowed to walk into history.

Before moving on to the next department, I want to mention the wonderful collection of Etruscan art (from Italy before the Roman period) on the balcony above the Roman section. One of the most outstanding pieces in this section is a bronze chariot from around 550 BCE. Having a preserved chariot is quite rare, so it is a treat to be able to see one so exquisitely decorated.

The Greek and Roman section leads direction to the collection of art from Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. Of course, one can tell at a glance that this grouping is a kind of mishmash of art from non-Western cultures, which in previous days was called “primitive.” In reality the arts of these three continents have nothing to do with each other; and, of course, the amount of geographical space supposedly represented in these galleries is incomparably more vast than that of Greco-Roman or Egyptian art. That being said, at least the Metropolitan has a fine collection of art from these parts of the world, which are too often ignored.

For my part, it is a great refreshment to go from the world of Greece and Rome to this gallery. Our culture has so internalized those classical forms that they charm us more for their “perfections” than for any surprises they contain. Thus it is a pleasure to sample some of the other great visual cultures from around the world, which really do contain surprises for Western eyes.

The grand hall of the collection (gallery 354) is one of the most spectacular in the museum. From the ceiling hangs an enormous collection of shields from Oceania, arranged into a kind of meta-shield formation. I am always reminded, incongruously, of a spaceship. Large sculptures fill the space below the shields. There are some slit gongs from the island of Vanuatu, which double as huge musical instruments and works of visual art. There are funerary sculptures from Papua New Guinea; called malaga carvings, they are beautiful and highly intricate wooden carvings meant to be used only temporarily to celebrate the dead, and then disposed of. (This certainly goes against the grain of Western thinking, wherein we want our art to be eternal.) The bis poles of the Asmata people, another culture in New Guinea, are used for a similar purpose, and are also beautifully carved and then disposed of.

The adjacent section on African art is equally captivating. During my last visit I was particularly attracted to a small wooden carving of a man, called a Power Figure, made by the Kongo peoples. Bent forward slightly, standing with arms akimbo, the statue has a real intensity when seen in person—the exaggerated form only magnified by the many steel nails emanating from the man’s body. More famous is the Benin ivory mask, a real masterpiece, made by the Edo people of Nigeria—one of the great pre-colonial states in sub-saharan Africa. The mask, which represents a powerful queen mother, is clearly the work of experts working within a vibrant tradition. The mask has an elegance and a graceful polish that make it very satisfying on the eye: each detail is finely crafted, and yet they all work together to make a perfect form.

During my last visit, I was especially interested in the section on pre-colonial American art, since I had just finished listening to an audio course on the peoples of North America. I was delighted to find beautiful examples of geometric pottery from the Ancestral Pueblo culture (fascinating to compare to the geometrical designs from pre-Classical Greece). Among the many sculptures on display, one of the most iconic is a ceramic baby from the Olmec culture, made around 1,000 BCE. It is a wonderful piece, surprisingly lifelike despite its stylized face. The folds of fat and the hand placed idly in the mouth serve to make this sculpture a far more realistic depiction of babyhood than the many portraits of the infant Jesus made over 2,000 years later in medieval Europe.

Moving on in our rapid tour, we come next to the museum’s Department of Modern and Contemporary art. The very fact that the Met has this department is a testament to its uniqueness. I can think of no other museum in the world that has significant holdings of ancient and non-Western art as well as “modern” art. But the Met is devoted to a vision of total universality—the art world’s equivalent of the Museum of Natural History—and so has it all.

The collection as the Met is almost as impressive as that in the MoMA—and that is saying a lot. Though there are so many great works on display, I will restrict myself to mentioning my favorite painting, which is also perhaps the most famous painting in the whole collection: Pablo Picasso’s portrait of Gertrude Stein.

It is an extraordinary portrait, arguably the greatest of the previous century. The painting is revolutionary. Gertrude Stein sits in a kind of abstract, unfinished space. She is not surrounded by her papers and books, but instead sits alone. While previous portraits in European art showed us the heroic and cultured male, handsome and lithe, Stein is hunched-over, short, and tick. Yet her body—mostly concealed under her heavy clothes—has a kind of elemental power on the canvass, even a monumental grandeur. But her face is what attracts the most attention. Rather than faithfully reproducing Stein, Picasso turns her face into a kind of mask. Thus her eyes and nose do not obey the normal rules of perspective and anatomy. Ironically, though this technique necessarily makes Stein’s face blank and inexpressive, the result is a convincing representation of the writer’s presence, of her indomitable energy. There is a charming story that, when told that Stein did not look anything like this portrait, Picasso responded “She will.” He was right: this portrait has helped to define Stein’s image far more than photographs of her.

I will also mention the largest work on display in this Department: America Today, a mural by Thomas Hart Benton. It consists of ten canvasses, and shows in visual form the America of the 1930s. The work was commissioned by the New School of Social Research—a kind of progressive think tank. I quite like the mural, as I do much of the public art created during the Great Depression and the New Deal. Looking at this work, one feels that we modern Americans were successfully creating our own visual language with which to decorate our public monuments—much like the Egyptians and the Greeks. The inclusion of this large mural is also keeping with the Met’s proclivity for immersive artistic experiences.

Next we come to the massive Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts. Once again, the Met excels when it comes to the re-creation of historical spaces. One of the most beautiful rooms in the Met is an entire patio taken from a Renaissance Spanish villa—the Castle of Veléz Blanco. Not only are the carvings on the arches and columns beautiful, but the space is filled with quite lovely statues of mythical, historical, and religious figures. Just as astounding is a study from the Ducal Palace of Gubbio. Every surface is covered in images made using the technique of wood inlay (intarsia, or marquestry), which consists of piecing together little bits of colored wood in order to make a complex image. The amount of time it must have taken to assemble a whole room this way is frankly stupefying. The result is an extraordinary work of immersive art, whose walls symbolize different areas of human activity. I am sure the room itself is a greater accomplishment than whatever happened inside it.

These two rooms only scratch the surface of the department’s holdings of decorative arts. There is everything one would expect to find in the homes of aristocrats and royalty, from elaborate coffee pots to ornate globes. I admit that, however fine these products are, they are generally less interesting to me than the sculptures.

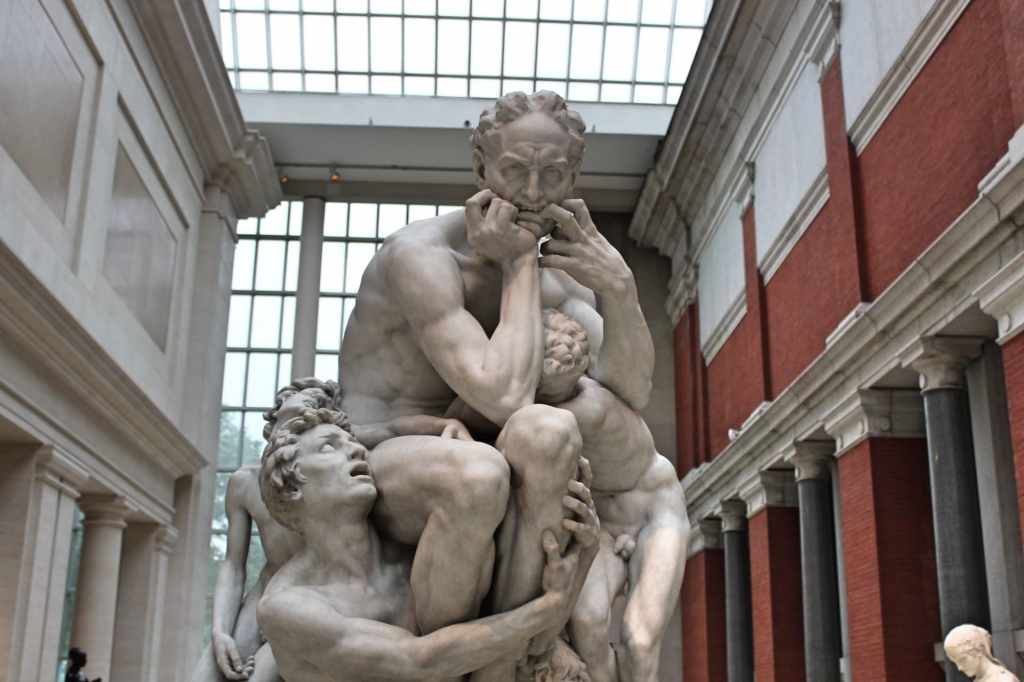

Some of the museum’s best sculptures can be found in gallery 548, which takes the form of a large atrium. On one side of the space, you can even see the brick façade of the museum’s original building (which is mostly buried in the later constructions). There are two outstanding statues in this space. The first is Perseus with the Head of Medusa, by Antonio Canova. It is an extremely fine work of Neoclassicism, achieving the idealized grace of the Greeks and Romans. Simply as a composition, the statue works marvelously, with the gruesome head balanced by the peculiarly barbed sword, making a strong diagonal. The other great statue (in my opinion) is Ugolino and his Sons, by Jean-Baptise Carpeux. This depicts a story taken out of Dante of an Italian count who—along with his sons and grandsons—was imprisoned and starved to death. We see the count, driven almost to insanity through starvation and despair, surrounded by the tortured forms of his progeny.

Continuing on through the museum, the visitor will next reach the museum’s section of Medieval Art. Now, I feel justified in mostly passing over this department, since the bulk of the museum’s medieval art resides in the Cloisters Museum, uptown (an enchanting branch of the Met). Even so, it must be said that the central room of the Medieval Department is a beautiful space, with a high ceiling and high windows, like a cathedral. An ornate grill (from the Valladolid Cathedral, in Spain) stretches most of the way to the ceiling, and charming examples of sculptures, tapestries, and stained glass give the space a properly church-like atmosphere. This last time around I was particularly impressed with the museum’s small collection of Byzantine art.

From here it is appropriate to go straight to the Department of Arms and Armor. As you can imagine, this was my favorite section to visit when I was a young kid, and did much to fuel my youthful obsession with swords and guns. Even now, I admit I find this section extremely impressive, and I have never seen any collection of historical weapons even half as good. The presentation is excellent. The visitor enters a large hall, where medieval flags are hanging from the ceiling. A group of mounted knights ride through the center, while other armored knights stand guard all around the periphery. One feels that one has entered a jousting tournament.

The suits of armor are fascinating and, often, strangely beautiful. They are like abstract sculptures of human forms, or a kind of proto-machine with moving parts. Though you naturally would think that a metal suit would be extremely cumbersome, you can see innumerable little joints made into the armor, giving the wearers a surprising range of movement. The most beautiful of these many suits on display is that made for Emperor Ferdinand I (brother of Charles V). Every piece of metal is covered in ornate designs. Just as wonderful are the Japanese suits of armor on display. Rather than turning their wearers into metallic turtles, this armor is clearly designed for a different sort of fighting—one requiring more lightness and flexibility. The monstrous grimaces on the helmets would be genuinely terrifying if someone was coming at you wearing this.

Right next to this department is the American Wing. This is one of the areas where the Met is really untouchable. Other museums may have finer paintings or sculptures or what have you, but I do not think any museum has such a complete and rich collection of American art. Indeed, the American Wing could be cut off and moved to a different spot, and it would still be one of the finest museums in the country. Its collection is vast, and it is so wonderfully presented. The visitor enters an enormous courtyard full of benches and statues. The glass wall and roof flood the space with light, making the department a welcome relief from the dark medieval section. Bright, colorful stained glass, and an equally colorful fountain, line the walls; and a beautiful bronze statue of Diana, lightly resting on one foot, occupies the center.

The visitor enters the main collection through a kind of pseudo-façade, as if this is an entirely different building. And, indeed, the visitor suddenly finds herself thrown into a richly-furnished home. In keeping with the museum’s penchant for interior spaces, there are a great many recreations of American interiors from different points in the country’s history. Surely, we have not invented anything as close to time travel as this. Proceeding onward, the visitor next finds a strange sort of room. It is in the shape of a large oval, and on the walls there is an enormous painting of the palace and the gardens of Versaille. When standing in the center of the room, the curving panoramic does create a satisfying illusion of actually standing in France. Just as the study in the Ducal Palace of Gubbio, this painting (by John Vanderlyn) must have taken a nauseating amount of time.

I walked up the stairs, and then found myself in what is called “open storage.” These are the chairs, tables, paintings, lamps, and everything else that the museum has but did not have the space to use. So they hang here, in transparent cases. I recommend a visit to this, if only because it gives you an idea of the enormous amount of material any major museum must be holding in storage.

Proceeding onward, we come to the painting gallery. There are far too many excellent works to name. I was particularly happy to see a portrait of Alexander Hamilton and George Washington—both of which used to hang in Hamilton’s home, up in Harlem. More conspicuously, there is the iconic painting of Washington Crossing the Delaware—almost ludicrously heroic. I was also happy to find Frederic Edwin Church’s painting, In the Heart of the Andes. Church was inspired by the naturalist, Alexander von Humboldt, and included as much scientific detail as he could in this painting. Just as famous is John Singer Sargeant’s painting, Madame X, an intentionally risque (at the time) portrait of a society beauty (her real name was Madame Pierre Gautreau).

I was most delighted to learn that the museum has an entire room designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. I am no expert in the design of houses or in interior decoration, but I must say that it is both a welcoming and an animating space. It is easy to imagine myself reading a good novel within, while watching the snow fall out the windows.

This completes our long circuit around the museum’s massive ground floor. If we continue on, we reach the Egyptian section again. So now let us return once again to the Great Hall, and then ascend the grand staircase to the museum’s first floor (or second floor, in America).

Finally we come to the museum’s collection of European Paintings. Now, I must be careful here to avoid getting pulled into an endless catalogue of the museum’s excellent works. Like the American Wing, the Met’s Department of European Paintings could be a self-standing museum, and still be one of the best in the nation. Whether you like Dutch, Italian, French, or Spanish art, you will not leave the gallery disappointed (though German painting is fairly absent).

As you might expect, I am most interested in the Spanish paintings on display. The Met has excellent examples of the three great Spanish masters: Velázquez, El Greco, and Goya. The outstanding work of Velázquez is a portrait of Juan de Pareja, an enslaved man of African descent, which the artist executed in Italy. You will be pleased to hear that the great painter freed Juan de Pareja, who went on to become a skilled painter himself (there is a work of his hanging in the Prado). In any case, when you look at this painting, you do not see a man in bondage. To the contrary, Juan de Pareja appears almost regal with dignity. The painting is beautiful and startlingly realistic. To depict a man of African descent in such a way was a radical gesture on Velazquez’s part.

Goya’s contribution is a portrait of Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga, a very young aristocrat. As usual with Goya, the figure has an odd stiffness, and the face is inexpressive. The viewer’s eye is naturally drawn to the scene at the boy’s feet, where two cats hungrily eye a magpie on a leash. This is a strangely morbid scene for a portrait of a youth, and it becomes all the more eerie when one considers that the boy died only a few years later, at the age of eight. El Greco’s outstanding work is his View of Toledo, the best of the artist’s few landscape paintings. As always, the artist’s signature style is immediately apparent: deep, rich colors combined with a dramatic verticality. This style is perfect for the city of Toledo—which is built on a hill overlooking a river, and filled with sharp towers. El Greco manages to imbue this wholly secular and inanimate scene with a burning spiritual intensity.

The number of excellent French painters in attendance dwarfs the representatives of any other nation. My personal favorite is Jacques Louis David. There is a charming portrait of the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier, who was executed during the French Revolution under false accusations. This is quite a historic loss, considering that Lavoisier is normally considered to be the father of modern chemistry. David’s more famous painting is his The Death of Socrates, a historical scene showing the great philosopher’s final moments. Socrates, who was very ugly and was quite old at the time, is shown as a partially nude Greek hero—with a muscular torso to boot. While I am not sure the painting captures the spirit of Plato’s dialogues, it is a brilliantly theatrical image.

On the subject of French painters, I must also mention The Love Letter, by Jean Honoré Fregonard, a delightfully coquettish image of a young woman receiving a note from her secret admirer. (I use this image in my blog’s newsletter.) I would love to keep going—since paintings speak to use in a modern language, easy for us to appreciate—but I will content myself with a short list of the artists in attendance: Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Vermeer, Ingres, Canaletto, Tiepollo, Turner, Klimt, Monet, Manet, Guaguin, Cézanne, Dürer, Memling, Rubens… Really even the list gets too long. The museum’s holdings of 19th century European paintings is so big, in fact, that the collection is held in a different section of the building.

To get there, you must pass a little hallway devoted to drawings, prints, and photographs. Now, you may be surprised to learn that, counted by individual works, this department is by far the biggest in the museum. But only a fraction of the drawings and prints in the museum’s holdings are on display at any given time. Sometimes they are taken out for special exhibitions, such as one on Michelangelo a few years ago. There, I got to see some of Michelangelo’s schematic drawings for fortresses, when he was briefly hired as a military engineer. Besides being innovative designs, the drawings themselves are beautiful works of abstract art.

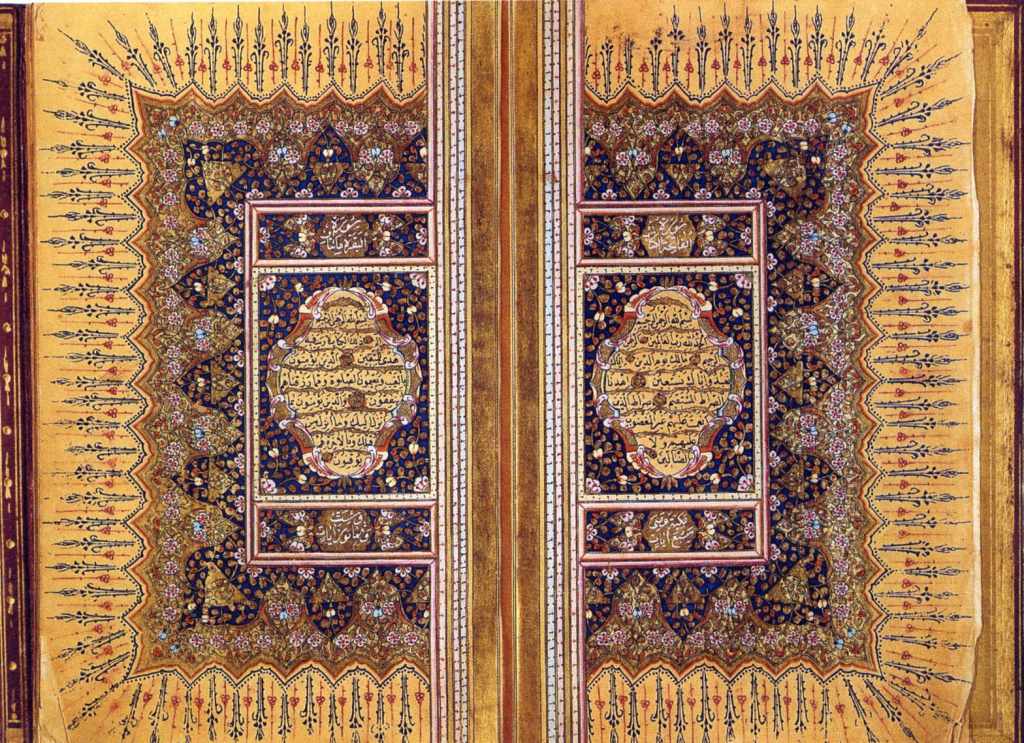

Continuing on through the paintings of 19th and early 20th century Europe—where you can admire the great impressionists and post-impressionists—you get to the Department of Islamic Art. During my time in Spain I have come to admire Islamic art for its intricate designs, its geometrical sophistication, and its sense of divine calm. Wonderfully creative patterns decorate everything from tiles, to carpets, to pages of the Qur’an. As an example of the last, there is a stunning illuminated Qur’an from Turkey, whose decoration is just as intricate as the Book of Kells in Dublin.

Representational art is relatively uncommon in the Islamic world, as it is explicitly forbidden by the religion, but there are still some examples in the gallery. A particularly beautiful one is a tile panel from Iran, executed in a style that looks to my ignorant eye as if it could be Indian. A seductively posed woman is being courted by a man wearing a European hat. I wonder who made object, for whom, and where it would be placed, since it seems to so flagrantly flout the strictures of Islamic religion.

In keeping with the museum’s love of historical spaces, this section has the Damascus Room. This is a winter reception room from a palace in Damascus, Syria, made around the year 1700. It is a beautiful space. Shelves display ornate ceramics and the gilded covers of Qur’ans. Panels of lovely calligraphy (bearing messages from the Qur’an) and floral designs decorate the walls, and the floor is covered with geometrical tiles. The ceiling is perhaps the most stunning of all, composed of elaborate woodwork. It is such a sophisticated, elegant space; it must certainly have set the tone for any conversations which took place within.

Next we come to the museum’s relatively small section on the Ancient Near East (Mesopotamia). For the most part these halls are filled with wonderful little objects from long ago, like cylinder seals, jewelry, incense burners, and small-scale statues. Among this last category is a small statue of Gudea, made around 2,000 BCE. It is a work of skilled craftsmanship, showing us a Sumerian king in a rather humble pose. His robe bears an inscription in cuneiform about his accomplishments (typical propaganda). What is striking is the thoughtfulness and even the humility of the king’s gaze and pose. He strikes us as more of a monk than a fearsome ruler. Another outstanding work is the bronze head of an unknown ruler, made between 2300 and 2000 BCE. Though not exactly realistic, I think this work is remarkable for the degree of individualization in the ruler’s features. We are not looking at a generic, stylized male head, but a particular man from 3,000 years ago.

But the real stars of this department are the lamassu: colossal sculptures of human-headed winged lions that flank the hallways. These were made in Assyria, around 850 BCE. Walking through this hallway, flanked by these mythical figures, feels like walking into the past. One detail I particularly like is that the creatures have five legs, as a result of a bit of illusionism. The front two legs are parallel, as if the creature is standing still; yet from the side, an extra leg is added (invisible from the front) to make it look as though the creature is mid-stride when seen from the side. The walls surrounding these stone guardians are covered with friezes in low relief, depicting other mythological scenes. For me, this Assyrian art is as lovely anything in the Egyptian section.

You emerge from ancient times onto the balcony overlooking the Great Hall. Here you can walk across and enter into the Department of Asian Art. This is one of my favorite areas of the museum, partly because of the art itself, and partly for the way that this department is laid out. Clever planning makes the department seem much bigger than it actually is, and walking through it the first time feels like exploring an old palace or temple.

The viewer enters the department by walking into a grand gallery, filled with enormous works of Chinese Buddhist art. There are large stele, bearing inscriptions and carvings, and a huge sculpture of a Bodhisattva. This may, in fact, be the biggest statue in the museum. It is 13’9’’ tall (over 4 m) and must weigh thousands of pounds. It is also quite beautiful, with richly decorated robes. On the wall is an even bigger paintings of the Buddha of Medicine, seated among a large retinue. It is a magnificent way to enter Asia.

From this large hall, one can either further explore Chinese art, on the left, or enter the arts of India, on the right. For the sake of consistency, we can begin with China. The Met’s collection of Chinese Buddhist sculpture is the largest outside of Asia, and more examples can be seen in Gallery 208. There are so many lovely sculptures. One I particularly like is a ceramic sculpture of an Arhat (or a Luohan, as they are known in China), which is a person who has achieved an advanced state of enlightenment. The sculpture is lifesize; and the man’s tired and worn expression is extremely compelling. His robes are still brightly colored, even though this was made over 1,000 years ago.

The Met also has a wonderful collection of Chinese drawings, calligraphy, pottery, and much else. But the most stunning room is the so-called Astor Court: a recreation of a Ming Dynasty-era courtyard. This is just another example of the stunning interiors from around the world collected at the Met. Finished in 1981, this installation was built by hand, using traditional methods; and besides being a beautiful work of art, it represented a landmark in cultural exchange between communist China and the United States. You enter through a round doorway guarded by two stone beasts (one is reminded of the lamassu in the Ancient Near East). Immediately you find yourself in a different world. A sheltered walkway surrounds a garden filled with oddly shaped rocks. These are called Taihu stones; they are formed via water erosion at the foot of a particular mountain in China (Dongting), and they are abstract sculptures in their own right.

At the end of the garden is a large room, designed to be used as a study, I believe. Unlike the great European interiors of the Met, this room does not appear at all ostentatious. Rather it is spare, restrained, and tasteful. As in the Damascus Room, it is impossible not to be awed by the high degree of sophistication and elegance of the room and the adjoining garden. I cannot but help imagining myself as a Ming Dynasty scholar, sitting in the garden and contemplating some intellectual puzzle. The space seems to invite contemplation.

Next we shall enter India and Southeast Asia. But before that, I ought to mention the Met’s small but delightful collection of Korean art. It is all in one room, Gallery 233, and I quite like the space. All of the objects are diminutive, and many have a kind of geometrical simplicity and elegance which gives the space its own distinct aesthetic. But we have no time to stop and savor. We walk from China, through Korea, and into India.

For me, the standout objects in these galleries are the many small figurines of gods. Indian sculpture enchants me for the kind of whimsical energy it often possesses. Though magnificent, the many gods do not seem remote or beyond reach, but rather quite approachable and inviting. These galleries are arranged chronologically, so we begin at around 2,000 BCE—about as old as anything in the Egyptian or the Ancient Near East sections—and move towards the present. To pick just a few of my favorite examples, there is an Avalokiteshvara Padmapani from the 7th century, a Bodhisattva who seems to be coyly beckoning. Or there is a statue of Shiva as the Lord of Dance, wherein the god is shown mid-stride, dancing within a fiery circle.

Another favorite is Yashoda with the Infant Krisha, who is suckling the young diety at her breast. This sculpture is especially resonant for Westerners, since we also have a tradition of representing the sacred mother suckling the divine child. But the style is here so very different. Whereas Mary is de-sexualized as much as possible, Yashoda is nearly naked and her breasts are almost comically large (of course, I am looking at this sculpture as a Westerner). Indian art is, after all, famous for its erotic content. An excellent example of this is a sculpture of a loving couple in a passionate embrace, made in the 13th century. You may be surprised to learn that this was part of the decoration of a temple. Certainly you would never see anything similar on a gothic cathedral!

The last work I will mention is a statue of Ganesha from the 12th century. This elephant-headed god is the bestower of good fortune, and it is customary to make an offering before doing anything important. When I visited a few years ago, I was delighted to find that this practice extended into the museum: there were coins left at the base of the statue.

We still have Japan to cover, but first we must take a little detour. Standing near the end of the section on India and Southern Asia is a beautiful wooden ceiling. This comes from a Jain temple built in the late 16th century. The staircase underneath this roof leads up to a small gallery on the floor above, this one devoted to the arts of Tibet and Nepal. For my part, this is some of the coolest art that I have ever seen. Though thematically related to art in both the Chinese and the Indian sections, the art here has a peculiar intensity not found anywhere else. An example of this is the painting of Walse Ngampa, a wrathful deity of Tibetan Buddhism. The figure has an electrifying intensity, with two arms wrapped around a terrified victim about to be devoured, while its many other arms are outstretched, holding symbolic objects.

When we descend, we can finally make our way to the section of Japanese art. Here, too, we can find some excellent statues. I particularly like the wooden guardian figures, which flank a statue of the Dainichi Nyorai, or the Cosmic Buddha. These guardian figures are formidable. I am always drawn to their fearsome grimaces. Even more wonderful is Ogata Korin’s ink drawing of waves on a folding panel. Here we can see a non-Western tradition of drawing that is intensely sophisticated. The waves do not occupy any kind of realistic space, but instead seem to emerge from nowhere and engulf everything. The lines of the waves are nothing like the blurry colors of Turner’s seascapes, which gives these waves a disturbing sense of solidity; the leading edge of the water appears sharp and even claw-like. It is a wonderful image.

We have already spent hours and hours in this museum, and yet there is still more to see. From the Japanese Department we can move on to the Department of Musical Instruments. This is housed in two galleries overlooking the section of Arms and Armor. I have never seen a collection of musical instrument that even comes close to the Met’s collection. There are superb examples of instruments from around the world: Italian harpsichords, Chinese pipas (similar to a lute), Native American rattles, Congolese horns, and Japanese drums. Seeing them in this context reminds us that instruments can be very beautiful simply as objects. To pick just one extravagant example, there is an Indian taus (a bowed lute) in the form of a peacock. And, of course, we must not neglect to mention the Stradivarius violins.

This gallery also has paintings with musical subjects hanging on the walls. My favorite is Dancing in Columbia, by Fernando Botero, if only because a copy of it has been hanging in my mother’s living room as far back as I can remember. Two balconies connect the two halves of the instrument department. On one of these is a charming old organ, and on the other is a fantastic assortment of wind instruments, arranged as if they are exploding from a central point. It is an evocative representation of a fanfare.

By now we have made our way through most of the major sections of the museum. There is only one place left on our tour: the Robert Lehman Collection.

Robert Lehman was a banker who owned one of the biggest and best private art collections in history. Active for a long time on the Metropolitan Board of Directors, he bequeathed his extraordinary collection to the Met, but on the condition that it not be mixed in with the other departments. Thus, the Met built a special space, attached at the back of the building, almost like a spaceship taking off from the main building. The rooms of the department are furnished to vaguely evoke a private home. Personally, I do not like having this department separate, since I do not see any good reason to do so other than vanity. If Lehman wanted his collection separate, he could have done what Frick or Morgan did, and established his own museum. But, in any case, there are some extraordinary works of art to be found, so it cannot be missed.

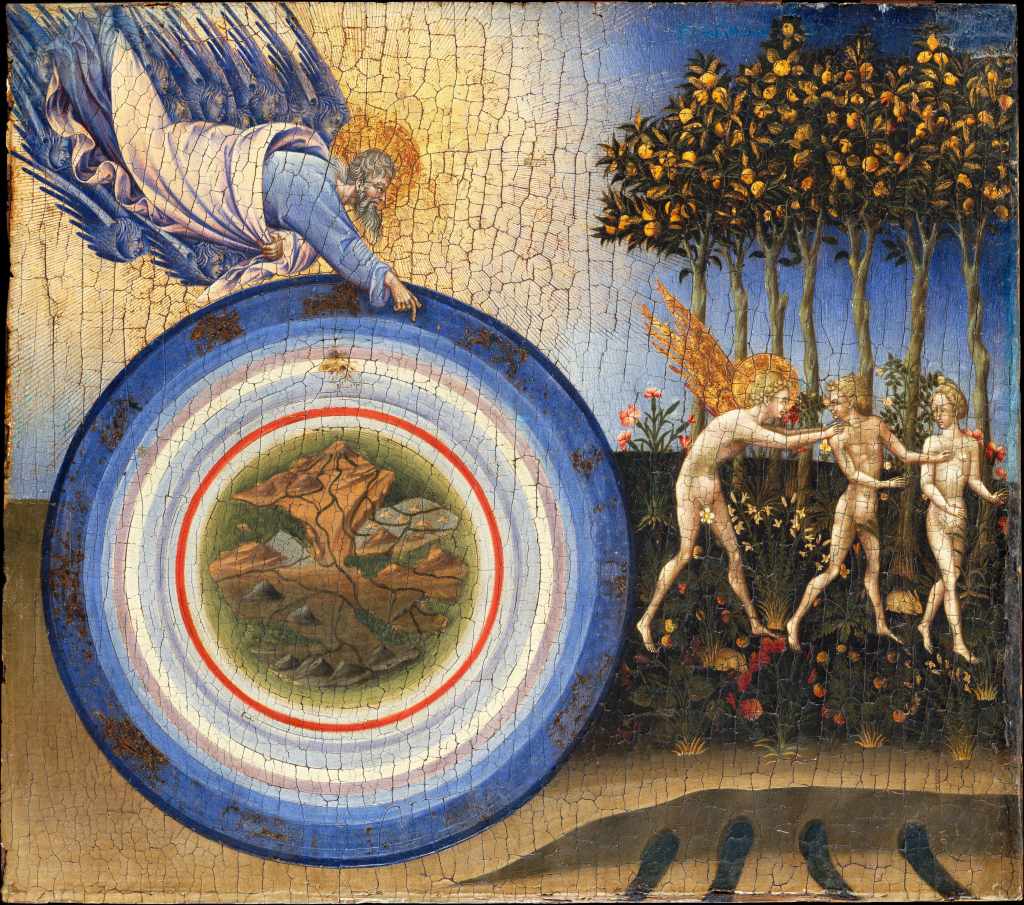

Robert Lehman seems to have been most interested in European paintings, and that is what we find in abundance. One of my favorites is The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise, by Giovanni di Paolo. I love the color palette of the paintings, filled with rich dark hues. But I am most drawn to the representation of the creation of the world: with God holding a series of concentric circles surrounding an image of Eden. Most famous, perhaps, is a portrait by Ingres of the Princesse de Broglie. Ingres’s technique is masterful, brilliantly capturing the rich fabric of her dress and furniture. It is also psychologically subtle, as it shows us a woman poised between shy reserve and self-assuredness.

There are dozens of other great paintings in this collection, and thousands upon thousands of great works in the museum, but this is where our tour must end. I have already written far too much. But the Met is endless—or, at least, it might as well be.

Confronted with such an enormous mass of culture and beauty from all around the world, it is difficult to know how to react. Part of me wonders whether all of these objects really should be here. With the financial resources that the Met possesses, the museum has been able to get nearly anything. But should they? And were all of the objects collected in ways that we would now approve of? Admittedly, the museum is trying to address this last question with their Provenance Project, paying particular attention to works that may have been looted by the Nazis and not restituted to their rightful owners. Personally I wonder about many of the objects in the Department of Oceanic, African, and American arts.

On the other hand, I think it is important that we do have spaces where we can see the human experience as one enormous tapestry. Traveling from Egypt, to China, to Turkey, to Senegal—in short, to nearly every inhabited corner of the world—and seeing these different traditions unfold through centuries of time: one would hope that this might lead to some insight into our human condition. There are some very obvious lessons, the most obvious one being that humans really like to make art. Other common themes are the relationships between art and power, or art and religion. It is all too much to really digest everything. But I hope every visit provides just a little bit more to chew on.

To conclude rather lamely, the Met is a uniquely excellent museum. Not only does it have vast and high-quality collections, but the museum is unique in many respects. As often mentioned, there is the museum’s emphasis on interior decoration and the arts of daily life. More important is the museum’s attempt to be all-inclusive: incorporating art from all over the world, and from every historical period. The Met’s view of art is expansive, incorporating not only paintings and sculptures, but swords, helmets, harpsichords, photographs, and dresses (the Costume Institute is downstairs). It is a kind of universal storehouse of human activity. I will surely keep going as long as my legs will take me.