Sons and Lovers by D.H. Lawrence

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

My reactions to this book veered from extremely positive to quite negative, so it is difficult to know how to begin. If you have an ear for prose, then Lawrence will seldom completely disappoint. At his best, Lawrence’s prose is lush, caressing, and aching. He evokes a kind of aesthetic tenderness that I have seldom experienced elsewhere—an intimacy between the reader and himself, a vulnerability that is disarming. In his strongest passages Lawrence is as meditative as Proust and as lyrical as Keats.

But this book is, unfortunately, not exclusively composed of Lawrence’s strongest passages. And as it wore on, I felt that Lawrence had exhausted his limited emotional range, and was overplaying his thematic material.

The premise of the book is quite simple: a woman in an unsatisfying marriage pours her emotions into her sons, who then become so dependent on her that they cannot form satisfying relationships for themselves. For me, there is nothing wrong with this (arrestingly Freudian) idea; but I did think that Lawrence beats the reader over the head with it. In general, I think it is unwise for any book to be too exclusively devoted to a theme. It does not leave enough room for levity, for spontaneity, for fresh air to blow through its pages. Sons and Lovers certainly suffers from this defect.

But the book’s faults become apparent only in the second half. I thought the beginning of the novel was quite astonishingly beautiful. Lawrence wrote of the sufferings of a young wife with amazing sympathy. He manages to bring out all the nobility and strength of Mrs. Morel, while avoiding portraying Mr. Morel in an unnecessarily harsh light. The miner is a flawed man in a crushing situation, and his wife is a resolute woman with few options. Their tragedy is as social as it is personal, which gives this section of the novel its great power.

When the focus shifts from Mrs. Morel to her son Paul, then the quality generally declines. Paul is not as interesting or as compelling as his mother; and his problems seem like sexual hang-ups or psychological limitations, rather than anything diagnostic of society at large. Perhaps our own social climate is just not ripe for this novel. Nowadays we are little disposed to care about the inability of a young man to find complete satisfaction in his relationships.

In fairness, there are charming and insightful sections in this second part of the novel as well. I liked Miriam as a character and I thought the dynamic between her and Paul was compelling, if a touch implausible. (On the other hand, I disliked the reconciliation between Clara and her pathetic husband.) Even so, I thought that the writing became noticeably worse as the book went on, as Lawrence inclined more and more to repetition. The characters speak, desire, recoil, hate each other, relapse, and so on. It is tiresome and it begins to wear on the reader, who longs for someone to do something decisive and bring all this emotional dithering to an end.

I am hopeful that Lawrence’s later novels have more of his strengths (his sympathy, his lyricism, his tenderness) and fewer of his weaknesses (his lack of range, his lack of humor). As for this one, I will end where I begin, with a confused shrug.

View all my reviews

Month: March 2020

Quotes & Commentary #74: Kahneman

We are prone to overestimate how much we understand about the world and underestimate the role of chance.

—Daniel Kahneman

Kahneman’s book, Thinking, Fast and Slow is one of the most subtly disturbing books that I have ever read. This is due to Kahneman’s ability to undermine our delusions. The book is one long demonstration that we are not nearly as clever as we think we are. Not only that, but the architecture of our brains makes us blind to our own blindness. We commit systematic cognitive errors repeatedly without ever suspecting that we do so. We make a travesty of rationality while considering ourselves the most reasonable of creatures.

As Kahneman repeatedly demonstrates, we are particularly bad when it comes to statistical information: distributions, tendencies, randomness. Our brains seem unable to come to terms with chance. Kahneman gives the example of the “hot hand” illusion in basketball—when we believe a player is more likely to make the next shot after making the last one—as an example of our insistence on projecting tendencies onto random sets of data. Another example is from history. Looking at the bombed-out areas of their city, Londers began to suspect that the German Luftwaffe was deliberately sparing certain sections of the city for some unknown reason. However, mathematical analysis revealed that the bombing pattern was consistent with randomness.

The fundamental error we humans commit is a refusal to see chance. Chance, for our brains, is not an explanation at all, but rather something to be explained. We want to see a cause—a reason why something is the way it is. We do this automatically. When we see videos of animals, we automatically attribute to them human emotions and motivations. Even when we talk about inanimate things like genes and computers, we cannot help using causal language. We say genes “want” to reproduce, or a computer “is trying” to do such and such.

A straightforward consequence of this tendency is our tendency to see ourselves as “in control” of random outcomes. The best example of this may be the humble lottery ticket. Even though the chance of winning the lottery is necessarily equal for any given number, people are more likely to buy a ticket when they can pick their own number. This is because of the illusion that some numbers are “luckier” than others, or that there is a skill involved in choosing a number. This is called the ‘illusion of control,’ and it is pervasive. Just as we humans cannot help seeing events as causally connected, we also crave a sense of control: we want to be that cause.

The illusion of control is well-demonstrated, and is likely one of the psychological underpinnings of religious and superstitious behavior. When we are faced with an outcome largely out of our control, we grasp at straws. This is famously true in baseball, especially with batters, who are notoriously prone to superstition. When even the greatest possible skill cannot guarantee regular outcomes, we supplement skill with “luck”—lucky clothes, lucky foods, lucky routines, and so on.

The origins of our belief in gods may have something to do with this search for control. We tend to see natural events like droughts and plagues as impregnated with meaning, as if they were built by conscious creatures like us. And as our ancestors strove to influence the natural world with ritual, we imagined ourselves as causes, too—as able to control, to some extent, the wrath of the gods by appeasing them.

As with all cognitive illusions, these notions are insulated from negative evidence. Disproving them is all but impossible. Once you are convinced that you are in control of an event, any (random) success will reinforce your idea, and any (random) failure can be attributed to some slight mistake on your part. The logic is thus self-reinforcing. If, for example, you believe that eating carrots will guarantee you bat a home run, then any failure to bat a home run can be attributed to not having eaten just the right amount of carrots, at the right time, and so on. This sort of logic is so nefarious because, once you begin to think along these lines, experience cannot provide the route out.

I bring up this illusion because I cannot help seeing instances of it in our response to the coronavirus. In the face of danger and uncertainty, everyone naturally wants a sense of control. We ask: What can I do to make myself safe? Solutions take the form of strangely specific directives: stay six feet apart, wash your hands for twenty seconds, sneeze into your elbow. And many people are going further than the health authorities are advising—wearing masks and gloves even when they are not sick, disinfecting all their groceries, obsessively cleaning clothes, and so on. I even saw a man the other day who put little rubber bags on his dog’s paws, presumably so that the dog would not track coronavirus back into the house.

Now, do not get me wrong: I think we should follow the advice of the relevant specialists. But there does seem to be some uncertainty in the solutions, which does not inspire confidence. For example, here in Europe we are being told to stand one meter apart, while in the United States the distance is six feet—nearly twice as far. Here in Spain I have seen recommendations for handwashing from between 40 and 60 seconds, while in the United States it is 20 seconds. It is difficult to resist the conclusion that these numbers are arbitrary.

If Michael Osterholm is to be believed—and he is one of the United States’ top experts on infectious disease—then many of these measures are not based on hard evidence. According to him, it is quite possible that the virus spreads more than six feet in the air. And he doubts that all of our disinfecting has much effect on the virus’s spread, as he thinks that it is primarily not through surface contact but through breathing that we catch it. Keep in mind that, a week or so ago, we were told that we could stop it through handwashing and avoiding touching our own faces.

Telling people that they are powerless is not, however, a very inspiring message. Perhaps there is good psychology in advocating certain rituals, even if they are not particularly effective, since it can aid compliance in other, more effective, measures like social distancing. Rituals do serve a purpose, both psychological and social. Rituals help to focus people’s attention, to reassure them, and to increase social cohesion. These are not negligible benefits.

So far, I think that the authorities have only been partially effective in their messaging to the public. They have been particularly bad when it comes to masks. This is because the public was told two contradictory messages: Masks are useless, and doctors and nurses need them. I think people caught on to this dissonance, and thus continued to buy and wear masks in large numbers. Meanwhile, the truth seems to be that masks, even surgical masks, are better than nothing (though Osterholm is very skeptical of that). Thus, if the public were told this truth—that masks might help a little bit, but since we do not have enough of them we ought to let healthcare workers use them—perhaps there would be less hoarding.

Another failure on the mask front has been due to bad psychology. People were told only to wear masks when they were sick. However, if we follow this measure, masks will become a mark of infection, and will instantly turn wearers into pariahs. (What is more, many people are infectious when they do not know it.) In this case, ritualistic use of masks may be wise, since it will eliminate the shame while perhaps marginally reducing infection rates.

The wisest course, then, may indeed involve a bit of ritual, at least for the time being. In the absence of conclusive evidence for many of these measures, it is likely the best that we can do. I will certainly abide by what the health authorities instruct me to do. But the lessons of psychology do cause a little pinprick in my brain, as I repeatedly wonder if we are just grasping at a sense of control in a situation that is for the most part completely beyond our means to control it.

I certainly crave a sense of control. Though I have not been obsessively disinfecting everything in my house, I have been obsessively reading about the virus, hoping that knowledge will give me some sort of power. So far it has not, and I suspect this is not going to change.

Letters from Spain #19: Spanish Eating Culture

The next episode of my Spanish podcast is out, this one about Spanish eating culture. Here’s the link to apple podcasts:

And here’s the video:

See the transcript below:

Hello,

It’s been pretty hard for me to motivate myself to do this podcast lately, now that everything is so crazy. After all, this podcast is about life in Spain, and life in Spain has basically stopped thanks to the coronavirus. The streets are empty, the cafés are closed. Here in Spain, we’re not even allowed to go on walks or exercise in the open air, unlike people are in most other countries. So I can’t say I’ve seen a lot of Spanish life lately.

But all this isolation has given me a lot of time to think. And the lockdowns being carried out all around the world are creating rather interesting conditions to compare countries side by side. The way people will react to them is partly a result of culture, I think. To be honest, I’m quite surprised at how Spain is reacting to the lockdown. In my experience, Spanish people are being quite cooperative. The streets are mostly empty and I haven’t really seen any disobedience with my own eyes. It’s bringing out a sense of solidarity in Spanish culture that I’ve never seen before. Everyone seems quite willing to do their part. And every night, at 8 pm, everyone gathers on their balconies and cheers for the doctors and nurses. Some people are even cheering for the police!

I doubt that Americans will adjust so easily to a lockdown. Though they’re both recognizably Western cultures, I think Americans are more concerned with notions of freedom and rights than people are in Spain (where democracy is younger), and so I doubt many Americans will be comfortable with having police cars patrol their neighborhoods, giving big fines to anyone disobeying the orders. Speaking for myself, I admit that it does make me feel queasy. But maybe I’m wrong, and the crisis will bring out a sense of solidarity and cooperation in America, too. After all, I didn’t predict that Spanish people—who love going outside and being social—would adjust so easily to being inside.

Now that we’re seeing Italy and Spain hit hard by this disease, it makes me wonder if culture has something to do with this. In this podcast I’ve repeatedly talked about the Spaniards love of proximity. This is true on every level. They like high density living, they like getting real close when they talk to each other, they like crowded bars. Spanish people just want to be close. Also, physical contact is much more permissible here, and kissing and handshaking is done ritualistically. Another interesting point to consider is that Spaniards have a lot of cross-generational contact. Lots of people live with their parents well into their twenties, and Spanish people keep in very close touch with their elderly parents and grandparents, often going to visit them every other weekend. Unfortunately, all of these aspects of Spanish culture may have made them more susceptible.

Well, in this podcast I don’t want to speculate about the virus. Rather, I want to pay homage to one of my favorite aspects of Spanish culture: its eating culture. This is one of the things from my daily life that I really miss, and I very much hope that we can beat this virus as quickly as possible, so we can get back to the good life of food and drink.

There are some obvious differences between Spanish and American eating cultures. The most obvious is probably just the schedule. In Spain, you eat late. Typical time for lunch is 2-3, and for dinner it can be from 9 all the way to 11. Another obvious difference is the quantity of food consumed in each meal. In America we have pretty big breakfasts, medium-sized lunches, and big dinners. In Spain, breakfast is usually light, lunch is very big, and dinner is medium-sized. In general, portions in Spain are quite a bit smaller than they are in the US, but that’s not saying much I suppose.

To me, the most important differences in the eating culture aren’t the times or the portions, but the restaurant and bar culture. I think Spain has a claim to having the world’s greatest bar culture, and this is for a few reasons. One reason is that there are just so many. Spanish people love being in public, and the number of eating establishments reflects that. Madrid, for example, has over 15,000 bars and restaurants, which translates to 1 for every 211 residents. This means that everyone in the entire city could literally go to a bar or a restaurant at the same time, and there would be enough space. And the city basically does do that.* On any day, at any given hour, there are tons of people sitting in bars, cafés, and restaurants.

Becauses eating establishments are so common and so fundamental to Spanish life, they have a very different aesthetic as they do in America. In America we go to restaurants or bars on weekends, holidays, or for special occasions. For this reason, they put more effort into creating a special ambience with music and decoration. Many bars and restaurants in Madrid are not like that. They are bare-boned, no-frills (as one well-known website calls them). They’re just for hanging out. A big advantage is that there’s often no music, so you can have a decent conversation. Also, the lights are usually not dimmed, so you can see the people around you. The ambience is more like your own living room.

Another huge difference is the lack of a tipping culture. Americans don’t really realize how much tipping affects our eating experience. Aside from the simple fact of having to calculate and pay the tip—which I find pretty annoying, now that I’m used to not doing it—tipping has a big effect on the entire experience. Waiters are motivated to be ingratiating, accommodating, but also fast. They want you in and out as fast as comfortably possible, since more people in and out translates into more money for them. And they will bend over backwards to give you good service. In Spain, it’s not like that at all. Most places don’t care if you stay there all night. And getting the attention of a Spanish waiter is famously difficult. They don’t have to pretend to love you.

Personally, on the whole, I think it’s much, much better. I don’t like being rushed out of restaurants. And I find this whole ritual of deciding how much a waiter “deserves” to be demeaning. I think waiters should just be paid a living wage so they can do their jobs serving food without having to be actors, too. I can never entirely relax in an American restaurant because of the pressure I feel to finish, the constant questions of “Would you like anything else?” and “Is everything alright?” In a Spanish restaurant, you can be as comfortable as in your own living room.

Another interesting difference between Spanish and American eating establishments is that Spanish bars and restaurants can often be quite generic. Since eating out is sort of a special experience in America, we expect eat restaurant to have something special, something that sets it apart. But in Spain, where eating out is as common as eating in, restaurants can be pretty standard. I like this a lot, since you always know what there is and what you can get, no matter where you are. And it makes ordering a lot easier. For example, you don’t need to specify the beer you want. The beer is standard, and you just specify how big a glass you want. Also, you don’t need to choose the wine from an elaborate wine menu. You can just order “white” or “red” and you get the standard wine. It’s actually kind of liberating not to have to make so many choices. I’m not a connoisseur, after all.

The menus from Spanish restaurants can also be really very similar. That’s because, in Spain, the eating culture is much more based on a national tradition than it is in America. There are national dishes here and that’s what everyone eats most of the time. What sets restaurants apart is not anything special on their menu, but just the quality of a typical Spanish dish. One place might have really good paella, for example, and another place has really good tortilla. The funny thing is, if you haven’t had much Spanish food, you might not be able to appreciate the difference. But once you’ve eaten a lot of it, you realize that it’s worth looking for a really good tortilla.

To sum up, the greatest thing about Spanish eating culture is that it’s for everyone, all the time. It’s a beautiful part of Spanish life, and I think it is an important and even a fundamental part of Spanish life. I loved it before this crisis, and now that I am deprived of it I love it even more. So consider this my homage, my tribute, to a special part of the culture that I hope we will be able to return to as soon as possible.

*I made a mistake in the recorded version of this podcast, saying 1 bar per 21 residents. In reality, not every resident could go to a bar at once.

Quotes & Commentary #73: Keynes

It is a great fault of symbolic pseudo-mathematical methods of formalizing a system of economic analysis . . . that they expressly assume strict independence between the factors involved and lose all their cogency and authority if this hypothesis is disallowed.

—John Maynard Keynes

I ended my last commentary by swearing to leave off thinking about the coronavirus. Alas, I am weak. The situation is bleak and depressing; it has affected nearly every aspect of my life, from my free-time to my work, my exercise routines and my relationships; but it is also, if one can be excused for saying so, quite morbidly absorbing.

What especially occupies me is how those in charge will weigh the costs and benefits of their policies. Because the threat posed by coronavirus is so novel, because these decisions involve human life, and because it is difficult not to feel afraid, I think there is a certain moral repugnance that many feel toward this kind of thinking. However, as I argued in my previous post, I think truly moral action will require a thorough appraisal of all of the many potential consequences of action and inaction. This will make any choice that much more difficult, and I do not envy those who will have to make it.

As anyone familiar with the famous trolley problem knows, moral dilemmas often involve numbers. If the actor has to choose between a lower and a higher number of victims, one must choose the lower number. However, there are several refinements of the problem which show the limitations of our moral intuition. For example, respondents are willing to divert a runaway trolley onto a track where it will kill one person rather than five; but respondents are unwilling to push an enormously fat bystander onto the tracks to save five people. We seem to be willing to think in purely numerical terms only about those involved ‘in the situation’ and unwilling to do so with those we perceive as ‘outside the situation.’

Well, in case we are facing, virtually everyone is ‘inside the situation’; so this leads us to a numerical treatment. But of course this is not so simple. What should we be measuring and comparing, exactly? I raised the question in my last post about this calculus of harm, and how it seems impossible to compare different types and levels of harm. As hospitals get overwhelmed, however, and care begins to be rationed, doctors are forced to make difficult choices along these lines, giving treatment to patients with the highest chances of recovery. Politicians are now faced with a kind of society-level triage.

One obvious basis of comparison is the number of lives lost. This is how we think of the trolley problem. But I think there is a case for also considering the number of lived years lost. What is ethically preferable: allowing the death of one person, or allowing the lifespans of 10 people to be reduced by 20 years each? I cannot answer this question, but I do think that the answer is not easy or self-evident. Reducing somebody’s lifespan may not be ethically on a par with letting someone die, but it is still quite a heavy consideration.

Further down the line, ethically speaking, is quality of life. Though it seems egregious to weigh death against quality of life issues, in practice we do it all the time. Smoking, drinking, and driving carry a risk, and a certain number of people will die per year by engaging in these activities; but we accept the cost because, as a society, we apparently have decided that it is “worth it” in terms of our quality of life. But of course, this comparison is not exactly appropriate for the case of coronavirus, since we ourselves make the decision to smoke or drive, whereas the risk of coronavirus is not voluntary. Thus, to save lives we should be willing to accept a greater loss in quality of life in this case, since we cannot control our exposure to the risk.

How exactly we choose to weigh or balance these three levels of damage—lives lost, lives shortened, and lives made worse—is not something I am prepared to put into numbers. (I suppose some economist is already doing so.) But I think we are obligated to try to at least take all of them into account.

Now, the other set of variables we must consider are empirical. On the medical side, these are: the lethality of the virus and the percentage of the population likely to get infected. On the economic side there are obvious factors like unemployment and loss in GDP and so forth. There are also factors such as loss in standard of living, homelessness, and the poverty rate; and still more difficult to calculate variables like the rate of suicide and drug addiction likely to result.

One major problem is that we know all of these variables imperfectly, and in some cases very imperfectly. To take an obvious datum, there is the virus’s lethality rate. From the available numbers, in Italy the fatality rate appears as high as 8%, while in Germany it is as low as 0.5%. This huge range contains a great deal of uncertainty. On the one hand, there is a good case that Germany gives a more accurate picture of the virus’s lethality, since they have done the most testing, about 120,000 a day; and logically more testing gives a more accurate result. However, we should remember that the virus’s lethality rate is not a single, static number. It affects different demographics differently, and it also depends on the availability of treatment. All of these factors need to be taken into account to establish the virus’s risk.

Complicating the uncertainty is the fact that the virus can create mild or even no symptoms, thus leaving open the question of the total number of cases—a number that must be known to determine the lethality rate. Asked to offer an estimate of the total number of infected people in Spain (the registered number is about 45,000 as of now), mathematicians offered estimates ranging from 150,000 to 900,000—and, of course, these are little more than educated guesses. If the former figure is correct, it would put the lethality at around 2%, while if the latter is correct the lethality is about 0.4%: another big range.

Now that Spain is receiving a massive shipment of tests from China, our picture of the virus will likely become much more accurate in the coming days and weeks. (Actually, many of these tests are apparently worthless, so nevermind.*) However, one crucial datum is still missing from our knowledge: the total number who have already had the virus. To ascertain this, we will need to test for antibodies. It appears we will begin to have information on this front soon, as well, since the UK has purchased a great deal of at-home antibody tests. I believe other countries are following suit. Not only is this data crucial to accurately estimating the virus’s threat, but it is also of practical value, since those with antibodies will be in far less danger either of catching or of spreading the disease. (In the movie Contagion, those with antibodies are given little bracelets and allowed to travel freely.)

The New York Times has created an interesting tool for roughly estimating the potential toll of the virus. By adjusting the infection and fatality rate, we can examine the likely death toll. Of course, these rough calculations are limited in that they make the mistake Keynes highlights above—they assume an independence of variables. For example, the calculator shows how the coronavirus would match up with expected cancer and heart disease deaths. But of course more coronavirus deaths would likely mean fewer deaths from other causes, since many who would have died from other causes would succumb to coronavirus. (Other causes of death like traffic accidents may also go down because of the lockdown.) The proper way to make a final estimate, I believe, would be to see how many total deaths we have had in a year, and then compare that total with what we would reasonably expect to have had without the coronavirus.

As you can see, the problem of coming up with a grand calculation is difficult in the extreme. Even if we can ultimately ascertain all of the information we need—medical, economic, sociological—we will still have only an imperfect grasp of the situation. Indeed, Keynes’s warning is quite pertinent here, since every factor will be influencing every other. Unemployment affects access to health care, an overwhelmed health care system will be less effective across the board, and the fear of the virus alone has economic consequences. This makes the ‘trolley problem’ model misleading, since there are no entirely independent tracks that the trolley can be moving on. Any decision will affect virtually everyone in many different ways; and this makes the arithmetical approach limited.

Trump has said that the cure cannot be worse than the disease. Obviously, however, the decision is not a simple choice between economic and bodily well-being. This is what makes the decision so very subtle and complicated. Not only must we weigh sorts of damage in our ethical scales, but we also must be able to think synthetically about the whole society—the many ways in which its health and wealth are bound up together—in order to act appropriately.

Once again, I do not envy those who will have to make these choices.

Quotes & Commentary #72: Mill

The creed which accepts as the foundation of morals, Utility, or the Greatest Happiness Principle, holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness.

—John Stuart Mill

Like so many people on this fragile green globe, I have been thinking about this novel crisis. I find myself quite constantly frustrated, largely because we suddenly find ourselves in the position of reacting to a threat of unknown potency using uncertain means. I argued in my last post that our shift from total indifference to all-consuming concern cannot constitute a rational response. In this post I hope to explore what a rational, and ethical, response must comprise.

Governments around the world are in the tragic position of having to choose between saving a relatively small (but ever-growing) portion of the population from severe damage, and inflicting less acute damage on a much larger portion of the population.

In making decisions like this, I believe the only ethical principle that we turn to is the principle of utility. However, I do not think John Stuart Mill’s strong version—our duty is to promote happiness as much as possible—is feasible, at least not for individuals. My main criticism of such a formulation is that it would lead to basically unlimited duties on a person. Can a thoroughgoing utilitarian really enjoy a quiet tennis match when she could be, say, working in a soup kitchen? I do not think we can embrace an ethic that would demand a population of saints; and, besides, such an ethic would be self-defeating if actually put into practice, since each person who is trying to create the most happiness would, themselves, potentially be miserable.

Thus, when it comes to individual behavior, I think that a negative version of utilitarianism applies: that we ought to try to refrain from activities that cause pain, harm, or unhappiness. Playing a tennis match, then, is alright; but breaking someone’s arm is not. This, I believe, is the standard that should be applied to individuals.

A government, however, is different; and different standards apply. A government has the obligation not only to avoid doing harm, but to actively reduce misery as much as possible. Unlike an individual—who could not live with an unlimited obligation to reduce unhappiness—a government, as an institution, does not have to balance its own happiness against others’, and so has a greater ethical obligation.

With this principle in view, the requirement for an ethical action on the government’s part would be to reduce suffering as much as possible. Of course, creating an exact calculus of harm is difficult at best. How can you compare, say, one death and a hundred million headaches? Yet since we must act, and since we ought to act as ethically as possible, we have little choice but to make do with a certain amount of imprecision.

Another source of imprecision is, of course, that we cannot know the future, and we know even the present only imperfectly. Because of this ignorance, every act can have unforeseen consequences. This is why we cannot evaluate an action on the ends it achieves alone, but must consider what could be reasonably known about the probable consequences of an action at the time it was taken. This means we have to have a certain ethical lenience for actions taken at a low state of knowledge, especially if the best available knowledge was consulted at the time.

Aside from the test of morality, there is also a related test of rationality. To be rational means to be consistent. This means the same standard is applied to all of our actions, and that there are no special categories. An irrational ethic is necessarily an imperfect ethic, since it means at least some of its actions are less ethical than others. Many of our society’s injustices are cases of irrational ethics: holding people to different standards, giving out different rewards or punishments for the same actions, and so on.

I am trying to define what a rational, ethical response means, exactly, because I think very soon we will have to make more nuanced decisions about this crisis. So far the primary approach has been to institute lockdowns, with the idea of slowing the virus’s spread. Even though I think there is a strong argument that Western governments were culpably unprepared, locking things down now may be a rational response given the potential threat of the virus. But if we find that even thirty or forty days in confinement is not enough to put the virus on the defensive, then we will have to begin to weigh the social costs more carefully. Just as the real effectiveness of a lockdown remains to be seen, so is the social price still undetermined.

At the moment we are just coming to grips with the virus, and we are belatedly adopting a “better safe than sorry” policy. We are tracking the rising death tolls of the virus and focusing our attention quite exclusively on this crisis. This may be rational, considering the novelty of the virus and the currently unknown threat that it may pose. But as the crisis wears on, we will be forced to consider other factors. There is, after all, no guarantee that forty, fifty, or even sixty days of lockdown will make it safe for people to return to their daily lives. Michael Osterholm (an expert on infectious diseases) expects that the virus will be around until there is a vaccine, and that a vaccine will take 18 months at minimum.

Now, perhaps extraordinary measures and unlimited resources can reduce the time until we arrive at an effective vaccine. That is unknown. My worry is that a lockdown will begin to have very real negative effects on quite a huge number of people; and this will almost certainly happen before the vaccine is available. We in Madrid are one week into our lockdown so far. At the moment, the streets are mostly empty, and they are constantly patrolled by police who can give enormous fines for breaking curfew. Today I heard a loud and violent argument down the street as one person harassed another person for doing something outside (they were out of view). I can hear neighbors occasionally quarrelling through my window.

Arguments and tantrums are the least of our worry. A protracted lockdown will exacerbate mental health problems (some of which are quite serious) and put pressure on marriages, as the spike in Chinese divorces shows. In Spain, open air sport, like going on a walk or a run is forbidden. (Meanwhile, tobacco stores remain open, even though smoking is known as one of the risk factors of the disease.) How will this ban affect children if it is protracted? And how long are we prepared to keep children out of schools? Not only will they be learning less, but social interaction is crucial to childhood development. (Osterholm is skeptical of the school closures, since he thinks that there is little evidence that children are significant vectors of the disease, and many health personnel with children might be forced to stay home. The demographic data from Spain—which doubtless overestimates the fatality rate across the board, since testing has been limited—seems to bear him out.)

In Spain, the government has, at yet, not waived rental payments. For people living from paycheck to paycheck, and who have been laid off, what will they do on April 1st when rent is due? Even if we are released on April 12, how many people will be completely out of work at that time? How many people risk losing their jobs and their homes? If and when coronavirus has disappeared completely, it may take a damaged economy years to return to normal. How will people get by if thousands of businesses go bankrupt and unemployment remains high for the long term?

Economic damage may sound fanciful compared with a health crisis, but it translates into a reduced—sometimes a drastically reduced—quality of life for millions. In the scale of human suffering, poverty is not negligible. Yet if such considerations seem petty, we must also consider something that Nicholas Kristoff (among others) has written about extensively: the rise of “deaths of despair” among America’s working class. These deaths can result from drug overdose or suicide, and they have been on the rise because of the worsening plight of working class America. We must consider, then, that economic damage does not only reduce the quality of life for millions, but it can translate directly into fatalities.

More generally, economic failure has a pronounced effect on life expectancy, even if you try to control for other factors. To quote from Bryson’s book on the body: “Someone who is otherwise identical to you but poor—exercises as devotedly, sleeps as many hours, eats a similarly healthy diet, but just as less money in the bank—can expect to die between ten and fifteen years sooner.” So economics indeed translates into years of life.

Now, I am not advocating against the lockdown. As I said before, given our available information, it may be a good and rational response. I am saying that, in the long run, an ethical evaluation requires that we consider the complete social costs of these measures. Just as importantly, if the coronavirus is, indeed, here to stay, then a rational response requires that we act consistently towards this risk.

This is what I mean. At the moment, coronavirus deaths are treated as a special category. This may be rational if we can eliminate the threat in a reasonable amount of time. But if we cannot eliminate this threat, and it is, indeed, here to stay for a year or more, then I am not sure that this attitude can be rationally sustained. A rational ethic will require us to see the coronavirus as one of many potential causes of death—more dangerous, perhaps, but no more or less acceptable than any other cause of death.

After this long and perhaps silly post—which I hope will be the last thing I devote to the virus for a time—I will end on a more practical note.

From what I observe, I fear that we may not be learning quite the right lessons from China’s success. Donald McNeil (a science reporter for the New York Times) explains that the lockdown in China was only the necessary and not the sufficient reason for the country’s recovery. The lockdown was complemented by widespread testing and the government’s ability to isolate people from one another. A small town in Italy, Vò, was similarly able to halt the virus by testing all of its residents and isolating the infected. Mike Ryan, an expert at the World Health Organization, has recently offered the same advice—that a lockdown without other measures is not enough. Here in Spain, the testing resources are severely limited, and only available for serious cases (although this will change soon). People with mild symptoms are not isolated but are being told to stay in their homes, which could potentially mean infecting their whole family. I hope, then, that we can not only learn from China’s strictest measures, but also their most intelligent.

The Cathedral of Chartres

Europe is full of cathedrals. Some people weary of them quickly. After all, you get the basic idea after a couple visits: In front there is an impressive façade, with several magnificent doors; then the inside is composed of a nave and the two aisles that lead to the main altar; and of course you have the choir, the transept, and all the little chapels on the periphery. It is the same layout every time, with only minor exceptions and variations. And, of course, the artistic styles are fairly uniform, too. There are the Romanesque and the Gothic styles, and all of the standard tropes of Christianity: Jesus, Mary, the prophets, the evangelists, and all the various angels and saints.

But there are those, such as myself, who only grow more fascinated the more cathedrals they see. In fact, I think that it is only possible to appreciate a cathedral once you have acquired a certain background. Even if styles are fairly uniform across Europe, the level of execution certainly is not; and it takes some experience to tell the difference. But cathedrals are more than mere exercises in art, of course. They represent the greatest monuments of Europe’s most deeply spiritual age. Each one is suffused with a sensibility that is almost entirely foreign to the modern world: a pervading sense of the nothingness of this life in comparison with the life to come. Unlike the palace of Versailles—a building devoted to earthly power and splendor—a cathedral uses earthly art to evoke something otherworldly. Thus, while I find the effect of most palaces to be rather deadening, I always find a visit to a cathedral uplifting. Nowhere is this more the case than at Chartres.

Chartres is a fair-sized town in the vicinity of Paris. Trains leave several times a day from the the capital’s Montparnasse station, and the ride takes a little over an hour. For whatever reason, I had to struggle with the ticket machine, which did not seem to wish to give me a ticket. My uncle told me that he also needed help buying a ticket to Chartres, but none of the French people could understand him when he said “Chartres.” (I had the exact same situation with my Airbnb host. French people can be very particular when it comes to pronunciation. And “Chartres” is not easy to say correctly.) In any case, all of us ended up getting to the city in time.

Though doubtless once a beautiful medieval town, most of Chartres was sadly destroyed during the Second World War. The cathedral’s survival and preservation is little short of miraculous, considering the circumstances. Even if most of Chartres’s medieval architecture was burned or blown away, the town still has a robust memory of their heritage. When I arrived the people were having their annual medieval festival. There were archery contests, parades of drummers and flag-twirlers, a concert of period music, and even obstacle courses for the children. All the vendors were dressed in the appropriate medieval rags and caps. It was a lovely time.

But unfortunately my train tickets did not leave me with much time to appreciate the life of the town. I wanted to spend as much time in the cathedral as possible. My hope was to get a tour from the great Malcolm Miller, a famous scholar of the cathedral who has been giving tours since the late 50s, but that was not to be. When I walked in the cathedral, I had just missed an assembling tour group (not with him), and I decided to settle on the standard audioguide.

I am getting ahead of myself, however. First I should describe the cathedral’s distinctive profile. Chartres is immediately recognizable for its two non-matching towers. The north tower (on the left, facing the building) is quite notably taller than the south tower; and its style is also quite different. This is because a fire necessitated the rebuilding of the north tower, which was completed in the early 1500s. Stylistically, then, it is more recent, partaking of the flamboyant gothic. While superficially more resplendent, it is actually the less interesting of the two towers, as it is rather like that of many other cathedrals. The right tower, on the other hand, is an architectural marvel in its own right. It features a sloping octagonal stone spire, constructed without any interior framework to hold it up. This is quite an amazing feat, when you consider that it was completed in 1150. Even now, there is not a bigger stone spire anywhere.

The first impression, upon walking into the cathedral, is rather stark. Compared with the great Spanish cathedrals—Toledo, Seville, or Santiago—the cathedral of Chartres can seem, at first glance, disappointingly empty. Toledo’s cathedral, for example, is stuffed to the brim with every sort of artwork. The cathedral also lacks the ostentatious splendor of so many Italian churches—shimmering with color and gold. Chartres’ appeal is quite different. It is the beauty of form, line, and light. It is the architecture of purity. The walls, arches, and vaults are arranged with such exactitude that the final effect is like that of a brilliant mathematical proof: the manifestation of divine logic.

Admittedly, this sensation of purity is partly a result of a thorough cleaning that the cathedral underwent about ten years ago. Centuries of soot had accumulated on its walls, turning them a dusky gray. During the restoration, the walls and even the statues were cleaned, making everything appear an ethereal white. This cleaning was not without its controversy. Part of the romance of visiting old buildings, after all, is the overpowering sensation of age, the palpable weight of time. Making the buildings look as good as new does radically alter the effect. However, the decision was defended as being necessary to the building’s preservation. For my part, the restoration did bring out the extreme lightness of the structure.

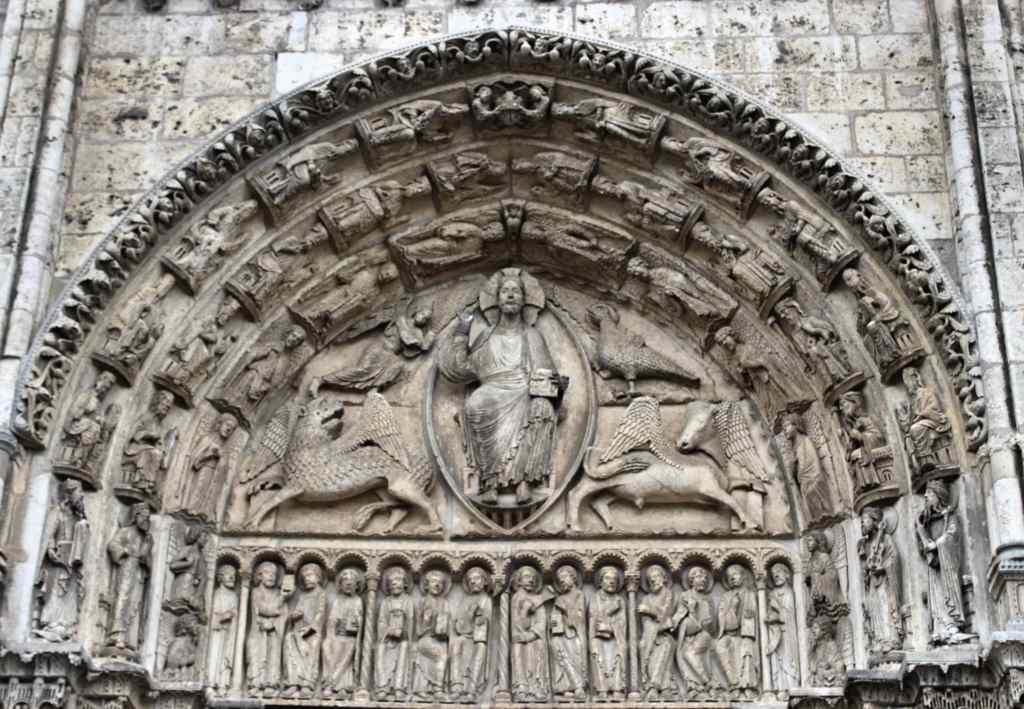

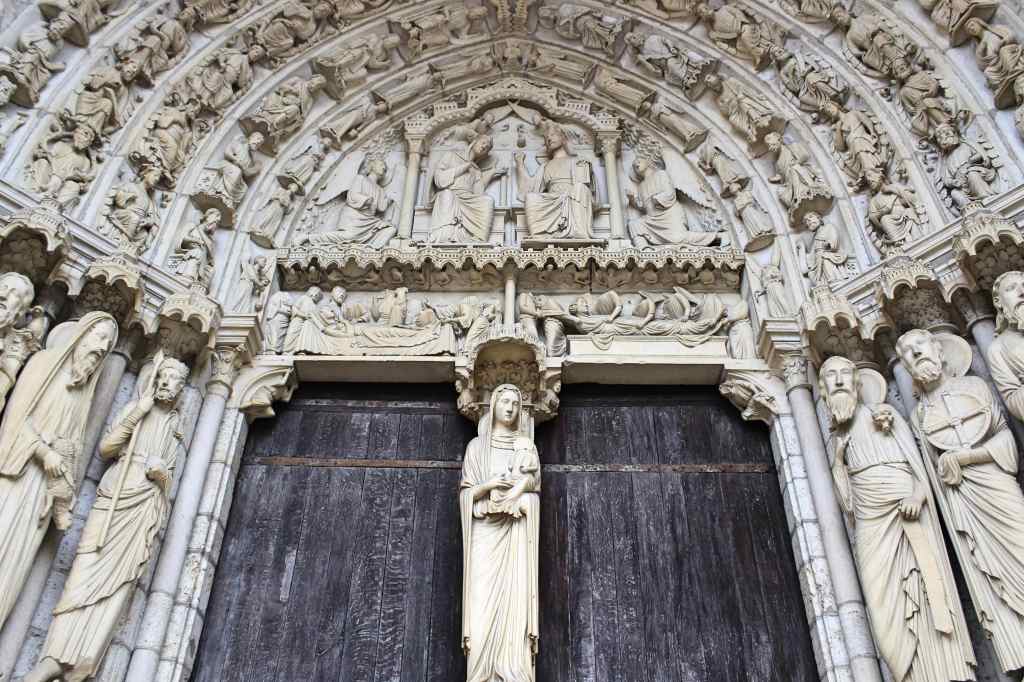

The audio guide first asks you to step back outside to examine the front portal. As with so many cathedrals, it consists of three doorways—one large one in the center, flanked by two smaller ones—lushly decorated with biblical figures. Appropriately enough, Christ sits enthroned in the center of the affair, surrounded by representations of the four evangelists. The most charming sculptures are not in the tympanums above the doors, however, but in the jambs separating the doorways. These elongated men and women are some of the sculptural masterpieces of the gothic age: they possess a certain majesty, mixed with a naive charm that I find difficult to describe. Even the decorative carvings between the human figures are varied and beautiful.

It is worth taking a closer look at these sculptures to spot the tiny personifications of the seven liberal arts (the trivium with the quadrivium). This marks the epoch when Chartres was at the forefront of European intellectual life. Before the time of universities, cathedrals were major intellectual centers; and the School of Chartres played a major role in shaping the scholastic thought that would dominate the European mind for centuries. The School of Chartres was distinct for its great emphasis on natural science, which was not always highly valued at the time. Indeed, you can see the scholars’ interest in both science and antiquity in one tiny figure, believed to represent the Greek philosopher Pythagoras. As Lawrence M. Principe said in his history of science, the middle ages are unfairly maligned as benighted.

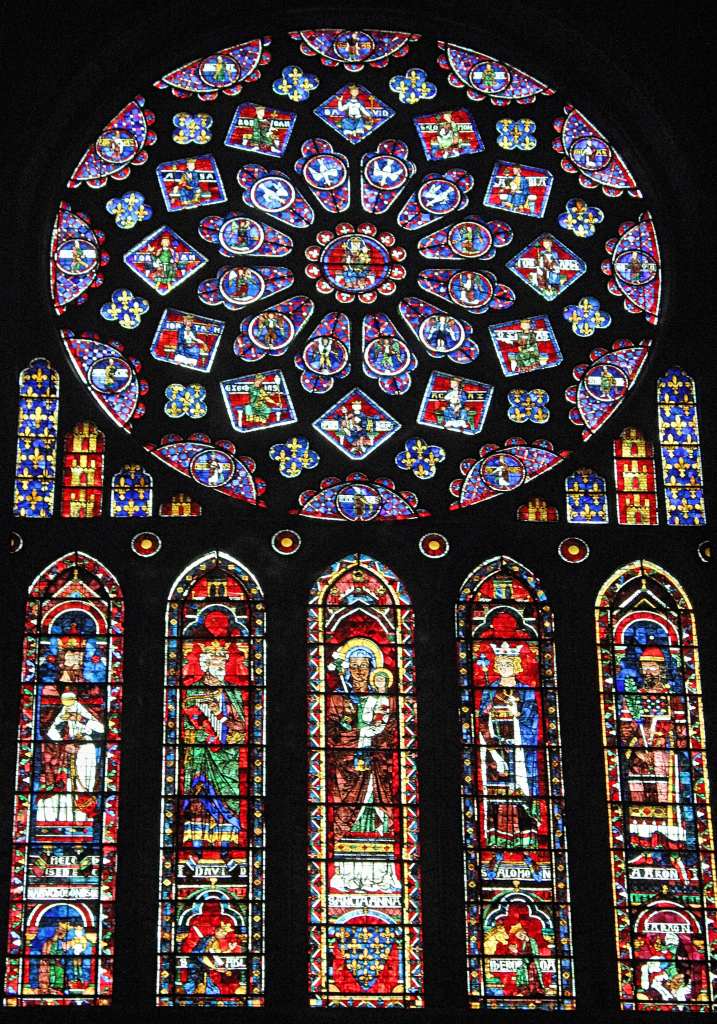

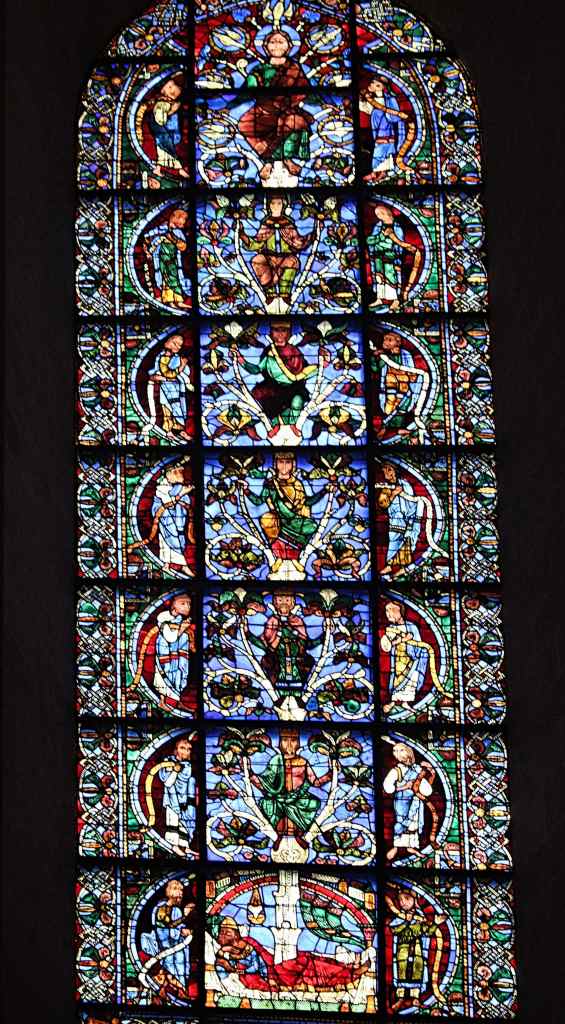

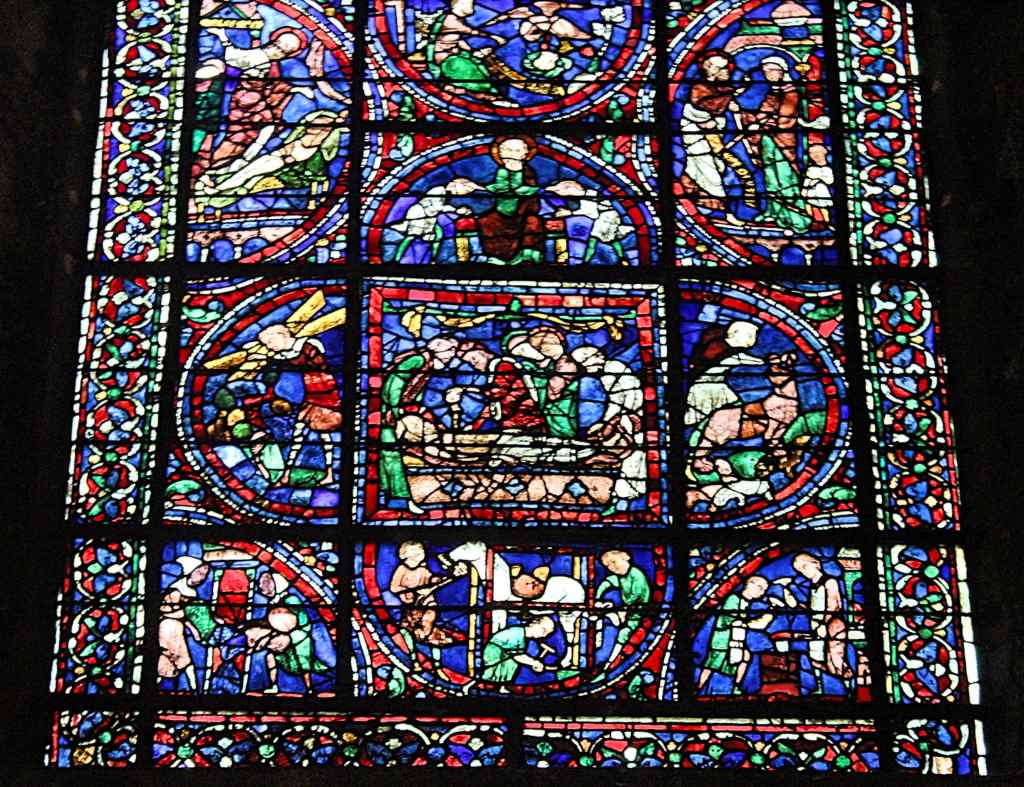

As soon as you walk inside, you must turn your attention to the windows. The stained-glass windows of Chartres are simply extraordinary. The quality of craftsmanship and art is excellent; and there is just so much of it. Normally, only a few windows receive the lavish treatment of elaborate pictorial representations, the rest being taken up with basic patterns. Not in Chartres: every window is bursting with detail. Describing even a fraction of these windows would be an enormous task. The audio guide had me walk around the entire length of the building, pausing before each set of windows, pointing out the most distinctive features. Each one merited close examination; but there are so many that you must budget your time and energy.

Some windows deserve special mention. The three rose windows—enormous circular panels above the three entrances—are magnificent, if difficult to see in detail from the ground. Indeed, many of the panels contain so many scenes—such as the Life of Christ, or the entire genealogy of Mary—that they overwhelm the viewer with information. One exception to this is the so-called Blue Virgin, a large representation of the Virgin with the Christ child. It is a wonderful piece of work, with Mary enshrouded in a glowing blue robe, while angels fly all about her. Though a difficult and expensive medium, Chartres shows that stained glass is quite the equal of painting or sculpture in its power.

My favorite windows were those around the aisles. These features several different panels, typically with a Biblical story occupying the main panel, with secondary scenes in the periphery. Curiously, many of these windows show craftsmen and laborers of different professions in the lower panel, such as shoemakers or blacksmiths. This is unusual in gothic art, and the guide explained that it was because the local guilds financed the windows. Recent research has thrown doubt upon this explanation, however, since it is unlikely that the guilds had nearly enough money. These scenes were perhaps included more as a gesture on behalf of the church, as a way of symbolizing its universal nature. Either way, it does give the cathedral a curiously democratic aspect.

The windows deserve far more attention than this. But I will let the images do the talking. Let us move on.

Chartres’s main altar would be glorious in another setting, but it seems somewhat out of place in the heavily gothic atmosphere of Chartres. It is an ornate, neoclassical sculpture in white marble of the assumption of Mary. It is clearly the work of a different age: the figures are carefully realistic and engaged in a dramatic action. The choir stall is another product of a later age (having been made in the 16th to 18th century), but it fits the aesthetic of the church rather better. It is beautifully carved with an endless number of details, providing a sculptural counterpoint to the complex windows above.

One of Chartres’s most recognizable features is the labyrinth. This takes the form of a circle, with one single path running from the beginning to the end point. It is meant as a symbol of the Christian’s path from sin to salvation, one long, winding road from the periphery to the center, a kind of miniature pilgrimage. (And the cathedral is, of course, part of the network of pilgrimage paths that lead to Santiago de Compostela, in Spain.) Simply as a design the labyrinth is quite lovely; and the more one examines it, the longer it seems. I wonder how long it would take to walk the entire distance.

The last stops on my visit were the north and south portals. The first is dedicated to the Virgin and the second to Christ’s crucifiction. In another context, virtually all of the sculptures in both doorways would be considered masterful by itself; in Chartres they are further extensions of the cathedral’s majesty. I was particularly taken with a group of Christian martyrs in the south portal, each of them holding a symbol of their identity. (I could not hope to identify the vast majority.) Though rather stiff by the standards of Renaissance sculpture, the bodies have a certain tension and dynamism, as if they are all on the lookout, that I found very appealing.

Thus concluded my audioguide’s visit to Chartres. Aware of the cathedral’s reputation, I was fully prepared to be awed; and I was not disappointed. But there were still a few delights in store for me. Right as I was about to walk out of the cathedral for the last time, a man began to give a lecture on organ music. He was seated high up above, in front of the keyboard, and speaking to an audience via a microphone; his image was projected onto a screen. I could not understand anything he said, since it was French, but it was obvious that he was giving some sort of a lecture on organ music, since every now and then he would demonstrate his point by playing the organ. It sounded fantastic. There are few more powerful feelings than hearing the ancient pipes of an organ resounding through the cavernous cathedral.

As I emerged onto the street, I was treated to another kind of music. Set up right in front of the cathedral, a group of four men were performing medieval songs on period instruments—simple jigs, mostly, with bouncing rhythms. It was quite a contrast to the somber and magnificent sound of the organ from a moment ago; yet it was a charming way to leave the atmosphere of the cathedral. Cathedrals exist to touch us in special moments, when we are able to see our own lives as very small in relation to something enormous that is above and all around us. This feeling engenders a sense of calm and even of detachment. Yet we cannot live our lives this way. We need rhythm, emotion, passion, too, if we want the full range of the human experience. The fullest life of all will contain moments of both passion and calm. And this is just what I experienced during my visit to Chartres

Quotes & Commentary #71: Kahneman

Those who know more forecast very slightly better than those who know less. But those with the most knowledge are often less reliable. The reason is that the person who acquires more knowledge develops an enhanced illusion of her skill and becomes unrealistically overconfident.

—Daniel Kahneman

Daniel Kahneman’s book—Thinking, Fast and Slow—is one long demonstration of the severe limitations of our human brain. He catalogues a variety of cognitive illusions and shows how they lead to persistently irrational behavior—so pervasive that we usually do not even notice it.

One of Kahneman’s best sections is on the limitations of expert judgment. He is devastating on the subject of political pundits—whose predictions Kahneman describes as worse than random—as well as on certain professions such as stock brokers. There are, in fact, many areas of human endeavor in which the final outcome is determined largely by chance, but which our brain insists on seeing as a contest of skill or produced by predictable causes. In reality, the world is far more unpredictable, uncontrollable, and unknowable than we all like to believe.

Now, Kahneman does not discount the possibility of real expertise. This would be an absurd position, as anyone who has played an expert chess player knows. In a great many situations experience and knowledge lead to increased effectiveness. But there are also many situations in which this is not the case. The key difference is whether the environment is regular or not. In a regular environment—one showing predictable patterns, such as when playing chess—then expertise is a major advantage. But in situations that are not regular, and which do not follow any predictable pattern (such as the stock market), the predictions of experts can be worse than random.

This seems like a particularly timely reminder during this coronavirus crisis. Suddenly we find ourselves in a novel situation, without historical precedent, and we naturally and logically turn to experts. But the experts that I have heard seem to sharply disagree on many important things.

A simple example is school closures. While some consider it wise, since children can serve as vectors for diseases, others consider it unwise, since the danger posed to children by the coronavirus is small and many healthcare workers have children (and so might be able to work less if schools were closed). Something else to consider is whether it might benefit the community as a whole if children developed immunity to the virus, thus negating their ability to serve as vectors. If they are at extremely low risk, then this could save many lives. Michael Osterholm seems to think that it is a bad idea, while most governments are coming to the opposite conclusion.

To give you two highly divergent cases of expert disagreement, consider Neil M. Ferguson and John P. A. Ioannidis. Ferguson is one of the world’s foremost experts on epidemics, whose titles are so extensive that I will not even repeat them here. His speciality is in mathematical models of infectious diseases; and his models predict quite bleak outcomes. He predicts one to over two million deaths in the United States, depending on the policies adopted. He recommends a policy of suppression—basically, a maximum of social distancing, locking down the population—in order to prevent the worst case-scenario. If we want to save as many lives as possible, then we will have to seriously disrupt society until a vaccine is developed, which may take quite a long time. (Ferguson himself recently seems to have come down with the disease.)

Ioannidis—the director of the Stanford Prevention Research Center—has a very different message. He emphasizes how much we still do not know about the virus, and how potentially foolish our methods of dealing with it may turn out to be. To take a basic datum, we are still quite in the dark regarding the lethality rate of the virus. It is tempting to take the total number of cases and then divide it by the total number of deaths, and get an answer. But there is reason to suspect that this would severely distort the results. For one, many countries have limitations on tests, and so the total number of infected will seem artificially low. And even if tests are widely available, we still cannot know how many people may be asymptomatic or have such mild symptoms that they never register.

To determine this we would need to conduct large-scale, randomized tests of the population, to see whether subjects have either the active virus or antibodies against it. To my knowledge, no such test has been done. Without such data, we really have no hopes of establishing the lethality of this novel coronavirus, because we cannot know how many people get mild or asymptomatic cases. In Italy and Spain, the virus appears to be extremely deadly. However, this is almost undoubtedly a result of several factors: for example, both countries have elderly populations; and testing is limited to those with serious cases. (Another interesting factor is that many younger people live with their parents in these two countries.)

If you look at South Korea or Germany—where testing is more widely available—the evidence seems much more reassuring. The Spanish newspaper El País calls the low mortality rate in Germany a “medical enigma,” partly because Germany’s population is roughly as old as Spain’s. But it is entirely possible that it is a more accurate picture of the virus than other countries. In Spain there are 625 tests per million people; in Germany they have 4,000 and in South Korea over 5,000 per million. Logically, the greater the testing capacity, the more accurate the mortality rate. Furthermore, it is worth noting that even the best testing capacity might lead to misleadingly high mortality rates, since again tests are usually given to people with symptoms; thus the number of asymptomatic cases remains largely a guess.

The only situation in which an entire population was tested, to my knowledge, was the Diamond Princess cruise ship. Of the roughly 700 infections aboard, there were 7 deaths, giving a lethality rate of about 1%, and about 20% of the roughly 3,700 people aboard tested positive. (About 50% of those who tested positive were asymptomatic.) If 20% of, say, the United States got ill, and 1% of that 20% died, this would translate to 700,000 deaths. This is obviously bad. However, the case of the cruise ship has several factors that would make it seem a worst case-scenario. For example, cruise ships are more densely populated than even the biggest cities, more time is spent in common areas, and air is commonly recycled; thus, the total infection rate of the virus would be unusually high. Further, the population of cruise ships is significantly skewed towards the elderly, which would make the death rate unusually high as well.

Ioannidis argues that if we adjust our numbers to account for these significant differences, then the total number of deaths in the United States will be 10,000. In his words: “This sounds like a huge number, but it is buried within the noise of the estimate of deaths from ‘influenza-like illness.’” And it is worth remembering that in a bad flu season 70-80,000 people die in a year.

One can point to the dire situation in Italy as a counterargument, of course. But it is worth noting that a virus does not have to be particularly lethal to overwhelm the medical system; it just has to be quite infectious. This is what is known as the R0 number: the average number of viral transmissions per person. We believe the seasonal flu to have an R0 number of around 1, meaning that each sick person gets an average of one other person sick. But if the seasonal flu had a much higher R0 number, it could be enough to flood emergency rooms like we are seeing. This is because more total people would be infected in a much smaller window of time. Thus, the evidence still appears quite inconclusive as to the real lethality rate.

A great many other things are currently uncertain. Can we get infected more than once? How will changing weather affect the virus? And how infectious is the novel coronavirus, exactly? Without essential data such as these, we are all essentially flying blind.

Another problem is that the intense focus on the virus may only exacerbate our ignorance, not remedy it. Naturally, headlines focus on the growing numbers of cases and the growing number of the dead. Yet if the news suddenly began to track deaths from heart attacks or traffic accidents, the results would also seem catastrophic. Even on a normal day in America, the news can make it seem as if we are living in a war zone. The ugly reality—which we normally prefer not to think of—is that tens of thousands of people die every day, for all sorts of reasons. The question cannot be resolved by simply measuring the cases that come to our attention. We need to measure vulnerability and lethality against the relevant total, and not as simply a number that keeps rising.

We are thus faced with a difficult choice. If we underestimate the virus, and Ferguson is correct, we will condemn many people to die. But if the numbers used in Ferguson’s models are wrong—and we have no way of knowing this yet—then the measures intended to counteract the virus may inflict more harm than benefit, maybe much more. The virus is an unknown quantity, but so is the damage that could result from government lockdowns. Are we locking unhappy wives in with their abusive husbands? Are we inflicting severe psychological harm on vulnerable people? And if the economy cannot bounce back from this disruption, what will happen to those whose situation was already precarious? And these are just the immediate effects—not the economic or social fallout. The scale of such potential negative results is currently unforeseeable.

The major refrain of our reaction has been to “flatten the curve.” The basic idea is simple. The healthcare system can only attend to a very limited number of severe cases at any one time. So if we get an onslaught of cases in one sharp peak, then there will be no hope of using our limited resources to save what lives we can. This seems simple enough, but I think it leaves out some important considerations. First, the graphic that is normally represented is completely out of scale. The potential peak is not just twice as high as the dotted line, but many times as high (we do not know exactly how high yet). To spread out the curve to below the dotted line, we will require not just eight weeks of intervention, but many months. Can we impose a lockdown for half a year or more?

Another consideration is one brought up by Ioannidis. If our health care systems are, indeed, overwhelmed regardless of our interventions, then our interventions may only succeed in extending the time that our healthcare systems are overwhelmed. To speak in terms of the curves, “flattening the curve” is only a good idea if we can get it below the dotted line. If we cannot get the curve under the dotted line—as is already the case in Italy and in some parts of Spain—then we will only protract the period during which hospitals are over capacity. This means that there will be more time that victims of trauma, heart attacks, strokes, and so on will be unable to get treatment, which can result in more total lives lost. After all, we must deal with all of our usual health problems on top of this. People will still need to give birth.

Here is a piece of pure speculation—from somebody who is in no way an expert. In the 1918 flu pandemic, one reason the disease became so deadly is because of a natural selection process. Normally, mild strains of viruses are preferentially spread, since those with milder symptoms are out and about, spreading the virus, and those who are infectious stay put. But if a lockdown creates a similar situation as the First World War—wherein mild cases stay put (since we are in lockdown and they were in the trenches), while severe cases are the ones which spread via hospitals—then we may be preferentially selecting for more severe forms of the virus. Admittedly, I have not heard anyone respectable express this worry.

I have, however, heard experts express the worry that, by locking people in their homes, we are potentially shooting ourselves in the foot. This would be because it prevents the least vulnerable from developing immunity, which would go a long way in making the entire population less susceptible. This is called “herd immunity,” and it is the strategy urged by David L. Katz (another expert, the founding director of the Yale-Griffiths Prevention Center). His main point is that it is not sensible to shut down all of society if only certain members of society are seriously vulnerable, or in his words that a more “surgical” approach is needed. (Also, certain interventions, such as sending college kids to live with their older parents, do not seem sensible from any perspective.)

My worry is that governments are incentivized to badly underreact and then badly overcorrect. They underreact because each government wants calm, happy, and prosperous citizens, and disrupting life for a seemingly small threat is not politically advantageous. They will overreact because, in the face of a threat that can no longer be ignored, governments must be seen as maximally responsible. What is more, with heavy government intervention, any successful diminution in cases can be claimed as government success. Thus, governments are incentivized to take the most extreme measures available. Anything short of that will appear cavalier in retrospect if the disease is as bad as it may indeed be; and even if it is not as bad, any success will go to the credit of the government.

But everything in life is a tradeoff. Morally speaking, the government must weigh the damage inflicted by the virus against the damage inflicted on the suppression measures. And if both of these are totally unknown quantities—which seems to be the case—what then? We are past the point where we can say “better safe than sorry.” We risk being both sorry and unsafe.

My own feeling at the moment is one of intense frustration. The governments of Europe and the United States have given conflicting messages to its citizens and have been content to react rather than prepare. Given the sharp shift from blasé indifference to emergency measures, I can only conclude that we are not in a situation like that of an expert chess player, but more like that of a stock broker—trying our best to predict the unpredictable. As Bill Bryson goes at lengths to show, we are still quite astonishingly ignorant about a great many things in our own bodies, including disease. And as Ioannidis explains, we are still quite in the dark even when it comes to something as humble as the seasonal flu or common cold. We only have rough estimates of flu related deaths, because we cannot filter out other common diseases such as colds; and it is also possible to have multiple infections at once.

In any case, to me it seems quite clear that the government’s wild pivot from indifference to emergency cannot constitute a rational response. To act as if the virus is unimportant one moment and the only important thing on earth the next is not evidence of clear thinking. We are in a hurry to embrace policies whose effectiveness, sustainability, and collateral damage are unknown to combat a virus whose danger is undetermined. While we are all collectively obsessing over the coronavirus (since lately it is impossible to think of much else), perhaps it is wise to remember another of Kahneman’s findings: “Nothing in life is as important as you think it is when you are thinking about it.”

Quotes & Commentary #70: Graeber

Economies around the world have, increasingly, become vast engines for producing nonsense.

—David Graeber

Humans are strange creatures: we can twist any event to reinforce the beliefs that we already hold. One would hope that this were not the case; after all, the entire premise of science is that experiences can correct beliefs. But it seems that this is not always the case. The coronavirus crisis is showcasing this tendency in all its irrational glory. Everyone—from progressives to conservatives—is convinced that this crisis reveals why the other side was wrong. Yet this mental phenomenon does not even have to take a political form. Exercise fanatics, for example, will use the crisis to reinforce their obsession, while doomsday preppers must feel awfully vindicated right about now.

I suppose I should join this crowd and offer my own little pet theory. A few months ago I read the book Bullshit Jobs, by David Graeber, and was entranced. It describes a widespread phenomenon: that many people harbor the secret conviction that their job is absolutely pointless. Reading this was an immense emotional vindication for me, since I myself had worked a job that I found to be pointless, and I experienced many of the harmful psychological effects that Graeber describes. But the problem is more than psychological. I think all of us have run into people whose jobs seem to serve little to no socially beneficial function. This can take many forms. A secretary whose only job is to answer the phone three times a day; an administrator whose job is to get college professors to upload their syllabuses into a central database; or the many hundreds of thousands of people employed in the United States processing health insurance claims.

Now that so many sectors of the economy are essentially shut down, perhaps this will give us an opportunity to reflect on which jobs are bullshit and which are not. I am not suggesting, of course, that everyone who has been sent home has a useless job. To the contrary, I think that most parents with kids at home would agree (I hope) that teachers have quite a challenging and important job. Likewise, now that we are sorely missing the pleasures of bars and restaurants, we must be grateful to all the people who made that possible. During this dark time, the humble cashiers in our grocery stores have become heroes. And this is not to mention the garbage collectors, police officers, and above all the doctors and nurses.

My point is that so many jobs which are commonly seen as low-skill and which are thus badly paid are now the ones we are relying on, or missing, most of all. Meanwhile, the sorts of jobs that are lampooned in Graeber’s book—the corporate lawyers, the college administrators, the creative vice presidents—I suspect are not sorely missed. Perhaps, then, this will motivate us in the future to better compensate those in these normally overlooked professions. Of course, I must pause and remind myself of the basic economic principle of supply and demand. The market is not a moral machine (fortunately or unfortunately); and rewards are not given away for merit.

Still, we have the means to make people’s lives easier. One way—popularized most recently by Andrew Yang—is Universal Basic Income: simply giving every citizen a certain amount of money each month that would be enough to cover basic expenses. In attenuated form, this is what the government is already proposing to do during the crisis: mailing every American a check for $1,000 dollars to help the many people who are out of work. David Graeber is also in favor of the idea, partly because it would allow so many people to escape the world of bullshit work. That is, having a financial cushion would give people the freedom to leave their work when they feel they are not doing anything productive or valuable. And this freedom would make a big difference in the job market in general, since it would give employees far more negotiating power. Jobs would have to be reasonably appealing if they wished to attract people who already had enough money to live on. Thus, this could benefit those with highly-paid but useless work, as well as those with badly-paid but useful work.

Maybe it is inappropriate to think of utopian schemes while we are in the midst of a crisis. And of course I am guilty of the same sin of seeing the situation through my own ideology. I ended my review of Graeber’s book by calling for a movement dedicated towards the expansion of leisure time. Ironically, nowadays I greatly miss the freedom to go to work. When you actually believe that you are contributing to society, working becomes a great source of meaning in your life. A world without work is not one I want to live in. But if we can dream for a few moments, I would ask you to imagine a world where work is more flexible, more negociable, and more meaningful. Will this crisis edge us in that direction? Perhaps I can be indulged for a moment of optimism at a time when all the news is bad news.

Quotes & Commentary #69: Keynes

It is astonishing what foolish things one can temporarily believe if one thinks too long alone, particularly in economics (along with the other moral sciences), where it is often impossible to bring one’s ideas to a conclusive test either formal or experimental.

—John Maynard Keynes

I have been thinking a lot about Keynes lately, and not only because I am reading a massive biography of his life. Keynes is one of those perennial thinkers whom we can never seem to escape. He exerted enormous influence during his lifetime and dominated economic thought and policy for thirty years after his death. Then, as inevitably happened, the Keynesian orthodoxy became too successful for its own good. His ideas came to be taken for granted, and his innovations became the conventional wisdom that the cleverest economists of the next generation came to reject. This ushered in the age of Neoliberalism—with Margeret Thatcher, Ronald Reagen, and Milton Friedman as the great standard-bearers—and the decline in Keynesian thought.

And yet, whenever there is a serious problem with the economy, everyone instinctively returns to Keynes. It was he who most convincingly analyzed the sources of economic recession and depression, and then plotted a way out of it. He was writing, after all, in the wake of the Great Depression.

To oversimplify the basic idea of Keynes’s analysis, it is this: High unemployment leads to a lack of demand, and a lack of demand can push financial systems beyond the breaking point. Put another way, the economy can be envisioned as an enormously complex machine that is composed of millions of cogs. Some cogs are small, some are large, and all are connected—either proximally or distantly. If one small cog stops working, then it may cause some local disturbances, but the whole machine can continue to chug along. But if too many cogs fail at the same time, the machine can come to a grinding halt.

As the coronavirus shuts down huge sections of the economy, this is exactly the scenario we are facing. Waiters, bartenders, actors, musicians, taxi drivers, factory workers—so many people face lay-offs and unemployment as businesses prepare to shut down. Besides this, if we are locked into our homes, then there are now far fewer places where people can spend their money, even if they have money to spend. It is inevitable that some people will not be able to afford rent, that some businesses will go under, and that much of the money that is available to circulate will remain unused in bank accounts. People are not going to be buying houses, or cars, or dogs, or much of anything in the coming weeks (besides toilet paper, of course).

Now, in a capitalist economy, anyone’s problem is also my problem, since buying and spending are so intimately related. The money you spend eventually becomes the money I receive, and vice versa. Thus, if there is a increase in unemployment (limiting the money you receive), an increase in bankruptcies (limiting the money the banks receive), and a decrease in spending (limiting the money I receive), then we have a recipe for serious economic contraction. A wave of bankruptcies inevitably puts pressure on banks; and if banks begin to collapse, then we are in grave trouble. Whether or not we like to admit it, banks provide an essential service in the economy, one which we all rely on. To return to my crude cog analogy, the banks are some of the biggest cogs of all; and if they stop turning, nothing else can move.