Their Solitary Way by Roy Lotz

I am excited to announce that, at long last, my philosophical novel has been published and is now available!

I wrote this book about six years ago—before I even moved to Spain—but I have been steadily working on it since. A philosophical novel with dubious commercial prospects, it took a while before I could find a publisher willing to release it. Thankfully, Adelaide Books agreed, and turned my little project into a reality.

In short, if you have ever read one of my reviews and thought “Boy, I wish that lasted three hundred more pages!” then have I got good news for you—you can! But be advised: I wrote this book when I was working under the combined influence of Marcel Proust and Ludwig Wittgenstein. While I would not dare compare my poor novel to their works, it does suffer from the attempt to emulate them.

In any case, to repeat the novel’s acknowledgments: “I am thankful to be part of such a wonderful online community of readers, and indebted to many members for helping me learn and grow.” It is no exageration to say that this book would never have been written, much less published, without Goodreads and the readers of this blog. So thank you once again.

(Ebook versions will soon be available across various platforms. I have linked to the publisher’s website and Amazon above.)

View all my reviews

Month: February 2021

Review: The Autobiography of Malcolm X

The Autobiography of Malcolm X by Malcolm X

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

By some fateful coincidence, I find myself writing this review on the 55th anniversary of Malcolm X’s murder. The coincidence feels significant, if only because this is probably one of the most crucial books in my reading life. I originally encountered the little paperback in university—borrowed from a roommate who had to read it for a class. Though I had only the vaguest idea of who Malcolm X was, the book transfixed me, even dominated me. Every page felt like a gut punch. My love of reading was substantially deepened by the experience. One decade later, The Autobiography of Malcolm X has lost none of its power.

This book has so many things going for it that it is a challenge to focus on a few. For one, Haley has beautifully captured Malcolm X’s voice. You can really hear him speak through the page—with humor, with wit, with passion, and most of all with righteous anger. (This time around, I listened to Lawrence Fishburne’s excellent audio version, which brought an extra dimension of realism to Malcolm’s voice.) What is more, the story that he tells is simply a good story on any terms, even if it were all made up. His childhood poverty, his gradual introduction into the ‘hustling life’ (as he called it), his incarceration, his conversion, his betrayal, his journey to Mecca—a novelist would have difficulty coming up with anything better.

But what is most valuable book is, as Malcolm X himself says, its sociological import. The first time I read this, I thought of it mainly as a historical document. Yet the sad truth is that Malcolm X’s story is still very much possible—indeed, a reality—in the United States. All of the essential ingredients are still there: segregation (de facto if not de jure), limited job opportunities, and mass incarceration. Indeed, while some things have gotten better, and much has remained the same, in some ways things have gotten worse. For example, the US certainly imprisons more people nowadays (disproportionately POC) than in Malcolm X’s day. There is still a direct pipeline from the failing public school in the black neighborhood to the prison cell.

Malcolm X is often contrasted with Martin Luther King, Jr., for presenting a “violent” alternative to King’s non-violence. But the perspective that Malcolm X consistently articulates cannot be simply boiled down to violence. His essential point is that, if any group of people in the world had been treated like black people in America have been—enslaved, lynched, legally disenfranchised, economically shut out, thrown into jails—then they would be well within their rights to fight back, “by any means necessary.” One can hardly imagine a group of, say, German immigrants, after undergoing such an ordeal, marching “peacefully” for their rights. Few ethical or legal codes prohibit self-defense. And it is the height of moral hypocrisy to hold the oppressed to a higher ethical standard than the oppressors.

The best response to this I know is from James Baldwin, who, while conceding the premises, wrote: “Whoever debases others is debasing himself.” In other words, if blacks did unto whites what whites did unto blacks, they would do spiritual damage to themselves. Now, not being of any religious bent myself, I at first treated this as a vaguely mystical sentiment. But I have to admit that, during the presidency of Donald Trump, I gradually came to see the real, practical truth in this statement. Racism is really a kind of psychic rot—not localized simply to our attitudes about race, but spreading in all directions, poisoning our sense of justice, spoiling our intelligence, stultifying our emotions. Though Malcolm X never gave up his insistence on the right to self-defense, he agreed with Baldwin in treating racism, not simply as a matter of prejudice to overcome, but a gnawing cancer at the heart of the country, capable of destroying it. And, for my part, I am no longer inclined to view such statements as merely rhetorical.

So in addition to being a thrilling story, wonderfully told, The Autobiography of Malcolm X presents us with a challenging indictment of America—still as true and valid as when he spoke it, fifty five years ago. I think any citizen will be improved by wrestling with Malcolm’s story and his conclusions. But let us not forget the personality of Malcolm, the man—someone who radiates genuine charisma. For my part, what I find most appealing and inspiring in Malcolm X is his intellectual side. Deprived of a formal education, he largely educated himself in prison by reading voraciously. And this curiosity stayed with him all his life. He recounts the thrill of debating college students—white and black—during his speaking tours, and speaks wistfully of going back to school to get a degree, and filling up his days studying all sorts of arcane subjects. In a saner society, Malcolm X would certainly have become a respected member of the intelligentsia, pushing the bounds of knowledge. It is up to us to create such a society.

View all my reviews

Ancient Cities: Naples and Pompeii

Naples

Compared to Rome, Florence, Venice, and Milan—all meccas of European travel—Naples is like a disreputable cousin, or worse. Known for being dirty, run-down, and crime-ridden, Naples has none of the chic of Lombardy and none of the rustic charm of Tuscany. But this shady reputation has some advantage; for unlike those more popular destinations, Naples is still very much a city for Neopolitans.

Our plan to visit was multi-pronged. My brother Jay and my friend Greg had Fridays free, while myself and my friend Holden had Monday off. This led us to a strange, staggered schedule, wherein Jay and Greg would arrive Friday and leave Sunday, while Holden and I would arrive Saturday and leave very early Monday morning. But sometimes it is worth a bit of awkwardness and inconvenience to be with friends.

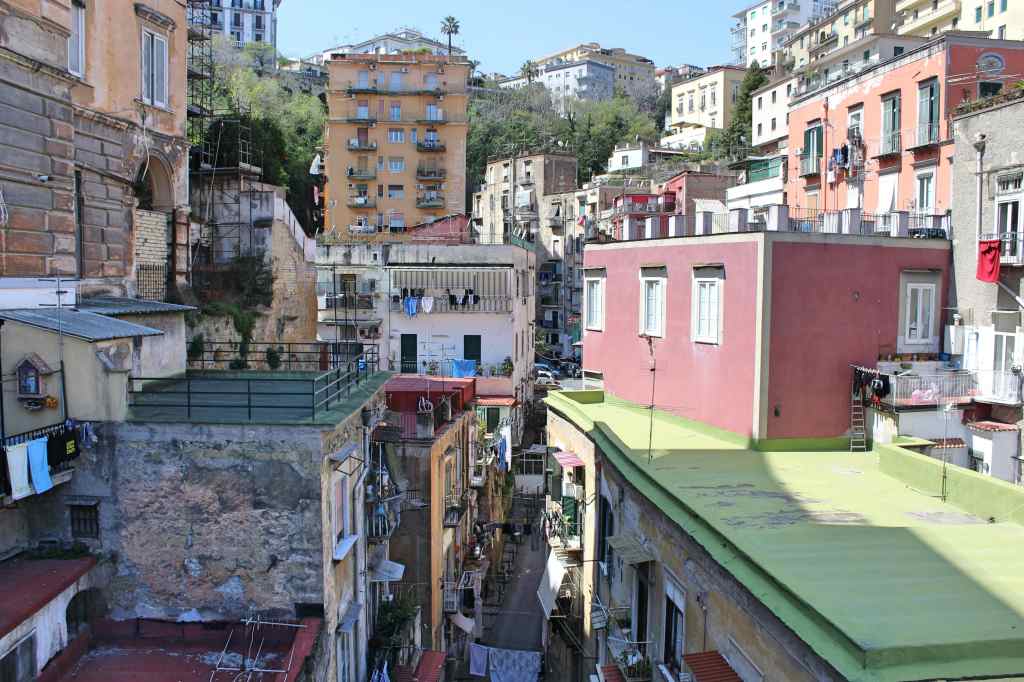

After a plane, a bus, and a metro ride, Holden and I arrived bright and bleary-eyed in the city. Immediately I was struck by the wonderful aesthetic of the city. Much like Marseille, the physical environment of Naples is a mixture of urban grittiness and Mediterranean beauty—the tan, brown, and yellow apartment buildings in various states of disrepair, graffiti sprayed onto every other surface, sun and sea a constant presence. But unlike Marseille, the energy of the city was pure anarchy. Mopeds and motorbikes zoomed by with wild abandon, neither stopping nor even looking, while the streets were filled with yelling, gesticulating citizens. It was, I admit, a little intimidating at first. But I soon decided it beat the more placid north by miles.

The chaos and commotion immediately reminded me of Seville or Granada. But I soon discovered that Naples did have one thing seldom found in Spain: street food. Famished from the journey, Holden and I stopped at a little café that had a take-away window. The display was filled with all sorts of fried delights—rice, vegetables, and meat that had all been rolled into a ball, coated in breadcrumbs, and cooked to a crisp. We ordered some morsels and sat down on a bench. From the first bite, I decided that I liked the place.

Soon, Greg and Jay appeared down the street in order to let us into the Airbnb. Greg, in fine form, was holding a blood orange (an Italian native), and making quite a mess as he ate it in the street. The Airbnb was in a big old building, slightly rundown but thoroughly charming in its Byzantine layout (we had to take two separate elevators to get to our apartment, since there wasn’t a straight path to the upper floors). In just a few minutes we were reunited and ready to meet this disreputable cousin.

Naples is one of the oldest cities in Europe, with a history stretching back far beyond the Romans. Prehistoric peoples had long been calling this area home when some impertinent Ancient Greeks established a major colony here. The Romans replaced the Greeks, and were in turn replaced by the Ostrogoths. Then the Normans came, and then the Spanish, and finally the French under Napoleon. Only after that, in 1815, did Naples definitively come under Neopolitan rule. A few decades later, while the United States was busy fighting its Civil War, Naples was finally integrated into the Kingdom of Italy. This quintessentially Italian city, then, has only been Italian for a century and a half—a short time for such a hoary place.

Naples is focused around its commodious bay. This has made the city a natural hub of trade and transport for thousands of years. Even today, Naples has one of the most important ports on the Mediterranean. This economic importance has resulted in urban accumulation. Naples is the third-biggest city in Italy, and its most densely populated. The whole place is huddled around the water like a group of children around a schoolyard fight. The streets are narrow and steep, and there are almost no parks within the city center itself to relieve the pressure. But every so often the claustrophobic city opens up into an enormous vista, revealing a giant cacophony of life spread out below the ominous form of Vesuvius. But more on that later.

Our first stop was lunch. And this, of course, had to be pizza, as Naples is the birthplace of that magnificent dish. It is difficult to pinpoint the exact birth of pizza. Bread topped with garlic and cheese is nearly as old as time, or at least agriculture. The missing ingredient was tomato, which had to make its way from the Americas to Italy. Thus, it was not until the early 19th century that pizza really came into its own. It is often told that the most iconic pizza of all, the Margherita pizza, was developed on the occasion of the eponymous queen’s visit to the city, where she sampled a pizza patriotically decorated with red (tomato sauce), green (basic), and white (mozzarella). This story may be partly fantasy; but there is a pizzeria in Naples—Brandi—which claims to be the originator of this now ubiquitous style.

We were famished, and so we headed into the nearest decent restaurant we could find. And as it happened, it was a lovely place. Totò, Eduardo e … Pasta e fagioli is a family style restaurant with a wonderful view of the city. It is not exactly a pizzeria—I assume it specializes in pasta e fagioli, another Italian classic—but, lucky for us, pizza was on the menu. And it was delicious. Neapolitan pizza is quite unlike what we normally eat in the United States. The crust is very thin, and so much tomato sauce is ladled on that it is normally eaten with a knife and fork. In contrast to a NY slice of pizza, then, wherein the lightly scorched crust is such a big component of the flavor, the taste of the Neapolitan version is dominated by the savory tomato and rich mozzarella. For my part, I was astounded at how addictively delicious the tomato sauce on my pizza was. Simple food, made well, can be stunning.

After the meal, we headed to the city’s major museum: the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. The entrance fee did seem a little steep to us, but I assure you that the collection is worth the price. The visitor is immediately greeted by the enormous head of a horse. This is a work by Donatello in imitation of a Roman original. The Renaissance master outdid both himself and his ancient counterparts, as the horse is a wonder of realism—with each individual tooth, subcutaneous vein, and fold of skin clearly visible. If memory serves, the statue is also significant for being one of the first bronze statues made since antiquity. It is, thus, both a technical and an artistic achievement.

But the bulk of the museum’s collection is devoted to the Romans and not the Renaissance. The first collection the visitor encounters is sculpture; and though many of the statues on display were unearthed in nearby Pompeii and Herculaneum, the most famous works, ironically, come from Rome itself. This is the Farnese Collection. It is situated here because of dynastic maneuvers. Pope Paul III, née Alessandro Farnese, acquired the major pieces of the collection during his papacy. But many years later, when the family lacked a male heir, Elisabetta Farnese became queen of Spain by marrying Philip V, and then passed on the collection to her son Charles, who became the king of Naples and eventually of Spain, too. In short, famous Roman statues acquired by a Renaissance Pope are in Naples because of a Spanish king. Europe can be a confusing place.

In any case, the collection is magnificent. There is Apollo playing the cithara, his robes and body sculpted from costly porphyry, while his head and extremities are white marble (a modern replacement of the original bronze). The statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton are significant more for their history than their beauty. Roman marble copies of lost Greek bronze originals, the statues depict the two men—lovers, of course—in the act of killing the last tyrant of Athens, thus paving the way for democracy. In the museum of Naples, then, we thus can a little taste of the Athenian Acropolis. Another group of statues commemorates military victories, both real and imagined, as it portrays an Amazon, a Giant, a Persian, and a Gaul—all warriors—all lying dead or dying.

But my favorite work of the bunch is the Farnese Hercules. Like so many great “Roman” works, it is actually a copy of a bronze Greek statue that was sadly destroyed when Christian Crusaders sacked the Christian city of Constantinople (they got sidetracked from battling Islam). At least we have this marble version, which is the most wonderful portrayal of that brawny Greek demi-god I know, as it shows both his humanity (he seems a bit tuckered out) as well as his monumental power. A close second is the statue of Atlas, with the world on his shoulders. This work is of some scientific interest, as the globe is supposed to represent the entire cosmos. As if the night sky were a sphere, and we were outside of it, we can see the major Greek constellations sitting atop the bent figure of the Titan.

Yet by far the most dazzling and virtuosic of the collections is the Farnese Bull. Carved from a single, enormous block of marble, weighing 24,000 kg (about 21 tons) it is the biggest statue to survive from antiquity. It also rivals the Laocoön Group in the Vatican for complexity. The statue depicts a now-obscure myth of Dirce, who is being murdered by a pair of twins, sons of Zeus. The two young men are tying the unhappy woman to a bull, who will either impale or trample her in short order, while in the background the twins’ mother watches it unfold. These human figures stand on a beautifully ornate base, and are accompanied by a barking dog and the visibly irate bull. It is a lot for the eyes to take in. Discovered along with the Hercules in the Baths of Carcalla, in Rome, the statue was restored by none other than Michelangelo. As such, it is difficult to say how much the work’s virtuosity owes to the Romans or to the Renaissance. Either way, it is supremely impressive.

Advancing from the sculptures—animals, busts, friezes, sarcophagi, cult statues, and equestrian figures—we come next to the mosaics. These are genuinely local, most having been taken from nearby sites like Pompeii. These are, in my opinion, some of the most charming works of art from antiquity, most of them intended to be interior decoration—images of heroes, deities, birds, and fish. But there is one mosaic in the museum that is far more than decoration: the Alexander Mosaic.

This extraordinary work was excavated from a Pompeiian villa. Though damaged, the essential scene is intact: Alexander the Great facing off against Darius III of Persia at the Battle of Issus. We can see the young and daring Macedonian pressing forward, as the distressed Persian Emperor is ready to turn tail and order a retreat. The mosaic is believed to be a copy of a Classical Greek painting, which would make it a fascinating window into the past, as none of the acclaimed Greek masterpieces have survived. But the Roman contribution cannot be neglected. Putting together a mosaic of this scale and complexity is a major feat by any standard. Over a millenia before the Renaissance we can see a highly sophisticated visual language. A variety of techniques—overlap, scale, foreshortening—are used to convey depth, while the figures show a range of dynamic movement that convincingly brings this battle scene to life.

Another major section of the museum are the frescos. These, too, are from nearby Pompeii and Herculaneum, and also served as interior decoration—the Roman version of fine wallpaper. Though faded, the color in many of these has held up remarkably well, partially because they are buon fresco, meaning that the paint was applied when the plaster was still wet, thus becoming part of the wall. This also meant that the painters had to work quickly, before the plaster dried. The style of these frescos vary from abstract designs of architectural fantasy and floral patterns, to landscapes or cityscapes, or more intimate scenes of daily life. For my part, the human figures have a kind of generic, cartoonish quality I do not care for. But in the views of cities we can see that the Romans developed a kind of quasi-perspective, using receding lines to give a realistic sense of depth. (In “true” perspectives all the receding lines must converge on the vanishing point, an innovation that the Romans did not develop.) And the abstract designs are quite superb. One can easily see why the re-discovery of Pompeii influenced 18th-century European style.

All of this art is lovely, and some of it magnificent. But nothing in the museum is quite as memorable as the Secret Cabinet (Gabinetto Segreto). This is the gallery devoted to erotic and obscene Roman art. Of course, the very notion of obscenity or pornography would likely have been foreign to the Romans, who did not separate sex into a special, taboo category. Pompeii was full of frank depictions of nudity and various sexual acts. But the Romans were especially fond of the phallus. This is usually explained by saying that the Romans thought that knobs brought good luck; but this only leads to the question—why willies? Perhaps they were meant to symbolize the masculinity of Roman culture—the macho ideal. One suspects that, at the very least, the Roman love of the membrum virile goes beyond the low humor of a middle school student doodling Johnsons in his notebook. Some of the art in this museum would have taken an awful lot of time and skill to make.

That is not to say it is not funny. There is, for example, a statue of a Roman wearing a toga, with a very conspicuous bulge in the crotch—the most elaborate dick joke in history, perhaps. Then there is the fascinus, the divine ding-a-ling, portrayed as a kind of strange winged wiener. This was taken very seriously by the Romans. One of the duties of the Vestal Virgins was, ironically to tend to the cult of this godly Roger. They were found all over Pompeii, apparently used as amulets to bring good luck. But, for the life of me, I do not see how anyone could look at a fascinus without a laugh.

After our unexpectedly risqué museum visit concluded, the evening was already coming on. So we decided to just enjoy the city. Even a casual stroll turned out to be exciting. Every shop seemed to spill out onto the street, with every sort of merchandise crowded onto racks and displays. Every sidewalk was full of pedestrians; and on every street a buzzing hive of motorcycles went by. The bars, we learned, served drinks to go—an important discovery. Then, we rounded one corner to find, of all things, a clown festival—the stage full of men and women wearing white makeup and red noses. Later, we learned that the city was having a piano festival: As we sat outside for another drink, a man gave a spontaneous performance of a piano sonata from a balcony. It was delightful.

Wandering along this way, we happened upon some of the city’s landmarks. We briefly went inside the Castel dell’Ovo, a castle that sits on a little island off the shore. Though the castle, as it stands today, is mostly medieval, a fortress has been on this island since at least the days of Rome. Not far off is the Galleria Umberto I, which is essentially a beautiful mall. Built in the late 1800s (during the reign of the eponymous monarch), the Galleria is a covered glass arcade, and includes shops, cafés, and private apartments in an attempt to create an integrated civic space. I have no idea if such utopian ideals were realized, but the building itself is a lovely relic from a classier age. The same description applies to the nearby Caffé Gambrinus. This is a coffeehouse from the Belle Epoque, so impeccably decorated that you feel as if you could be in a Wes Anderson film. We ordered some slightly overpriced (but good) coffee and pastries, and tried to imagine ourselves chit chatting with Guy de Maupaussant.

Right next door is the central square of Naples, the Piazza del Plebiscito. This plaza owes its name to the 1860 plebiscite, in which the people of Naples voted to unify with the Kingdom of Italy. It is an expansive space. On one side, the neoclassical church San Francesco di Paola extends colonnades to its left, to the Palazzo della Prefettura, and to its right, to the Palazzo Salerno, forming a kind of embrace. Opposite the church, the erstwhile Royal Palace presides, now bereft of purpose. Adorning this palace are a series of statues that illustrate the tumultuous history of Naples. The first statue is of a Norman conqueror, Roger II, who is followed by a French king, two Holy Roman Emperors, an Aragonese and a Spanish king, one of Napoleon’s generals, and finally an Italian: Victor Emmanuel II, the first king of a united Italy. This quintessentially Italian city has only been Italian for a short while.

For dinner, we decided to try another Neopolitan classic: fried pizza. This is exactly what it sounds like, dough formed into a kind of calzone shape, filled with cheese and tomato sauce, and then deep fried. Apparently the dish originated out of the desolation of the Second World War, when ingredients were scarce. Naturally, a fried pizza uses more flour and fewer toppings; and the dough puffs up during cooking. The four of us stopped at a takeaway place, and were soon gnawing on crunchy pizza dough in the street. I quite liked it. But I admit it could not compare with the genuine pizza we had eaten earlier.

On our way back to the Airbnb, we stumbled upon an enormous group of young people drinking in the street. (Writing this, I feel such nostalgia for the pre-Covid days!) We soon found out why: nearby was a bar selling Aperol spritzes for one euro a pop. The Aperol spritz is a drink that has yet to catch on in the US; but in most of Europe it is a summertime staple. Aperol is an herbaceous liquor, too bitter to be drunk on its own. But combined with a bit of prosecco, seltzer, and some lemon juice, it makes for a delightful refreshment. We idled around, swigging down the cheap plonk, and enjoying the nighttime ambience. But my brother happened to be feeling unwell (this was before cold symptoms sent shivers up our collective spine), so we went back to the Airbnb to drop him off. Greg, Holden, and I then continued our Aperol spritz binge in a nearby bar. And as the warm glow of alcohol fell over me, I listened to the mad rush of scooters zipping down the nearby street, and felt that wonderful, romantic feeling of being in a foreign place.

Pompeii

The next day, Greg and Jay had to catch their flights back to Marseille and Madrid, leaving Holden and I to explore another ancient city: Pompeii.

Getting to Pompeii from Naples is easy. Many people opt to take a tour, of course; but for those plebeians like me, the train is the way to go. There are two train lines that go to Pompeii, the Metropolitano and the aptly-named Circumvesuviana. Either one gets you to the site in around 40 minutes, plus a bit of walking.

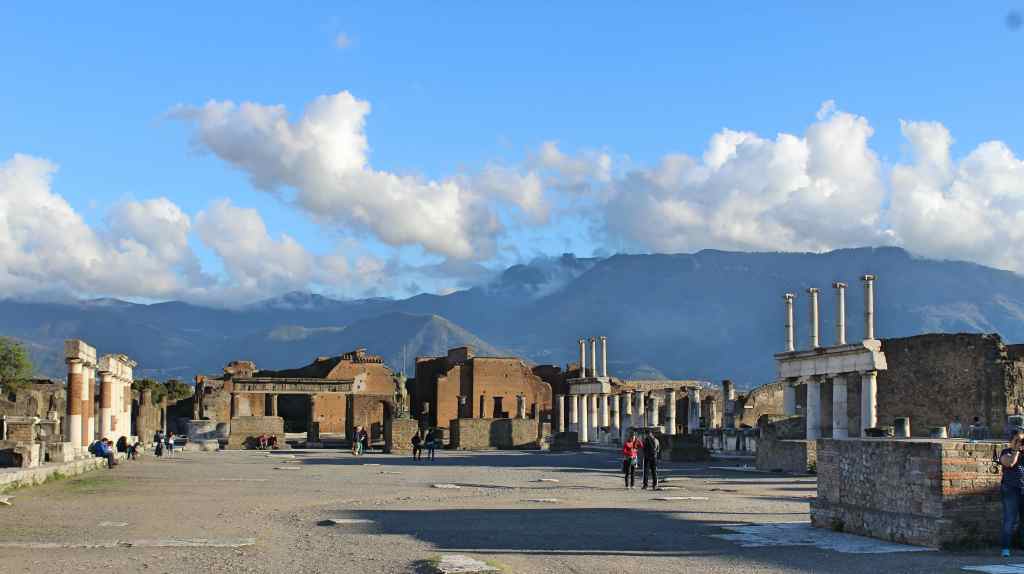

After the Colosseum, Pompeii is likely the most famous ancient Roman site. Everyone knows the story; and many of us can remember seeing those frightful plaster casts of the deceased, frozen in their last excruciating moments. Even so, when I walked into this iconic place, I really had little idea what to expect. Indeed, my first reaction was mild disappointment, if only because visiting Pompeii is so unlike visiting other famous monuments. Instead of glorious architecture or priceless artwork, the visitor is confronted with something far more humble: houses, apartments, streets, alleys… The buildings on display were not made to satisfy a king or celebrate god (at least not most of them). They are entirely cotidian. But it is the very ordinariness of Pompeii that makes it special. For it is here, more than almost anywhere else, that we can imagine what life was really like all those years ago.

Let us begin at the end, with the destruction of Pompeii. This was due to a catastrophic eruption of nearby Mt. Vesuvius (still an active volcano), in 79 CE. The traditional date given for this eruption is August 24, as this is the date provided in the letters of Pliny the Younger, the only surviving eyewitness account of the eruption. However, evidence found within the site—coins, clothes, produce—suggest that this day may be too early. Indeed, we know that medieval copyists (who preserved Pliny’s writings) were prone to errors. It now seems more likely, then, that the eruption took place in autumn, in late October or early November.

It also must be remembered that the eruption was a process, not a single moment. Tremors and earthquakes began to rock the city for days beforehand; and the first phase of the event consisted of hail of pumice, lasting many hours, which is normally not life-threatening. The residents of Pompeii thus had ample warning that something was happening, and had plenty of time to escape if they chose to. Most did. For the unlucky few who remained, the situation soon became far more dangerous. Pyroclastic flows—clouds of ash, extremely hot, moving at hundreds of miles per hour—streamed down the sides of the volcano. The physical impact alone was sometimes powerful enough to destroy buildings. But even if the building held firm, anyone sheltering inside was killed instantly by the arrival of the hot gas (after traveling the long distance from Vesuvius, the gas was still as hot as your oven at full whack).

In total, about 1,100 people lost their lives in the event, in a city of probably at least 20,000. What remained of the city was entombed beneath a layer of ash, 6 to 7 meters (19-23 ft) deep.

This eruption is forever connected to two Plinys—the younger, previously mentioned, and the Elder, his uncle. Pliny the Elder was a famous naturalist, remembered for assembling a massive encyclopedia of knowledge of the natural world, called the Naturalis Historiæ. When Vesuvius began to erupt, he was at his villa across the Bay, and set off on his boat on a rescue mission (as well as to collect some observations on volcanoes, one presumes). Unfortunately, the old man died in the attempt, apparently by breathing in toxic fumes from the volcano (though the other members of his party were unharmed). Meanwhile, the younger Pliny—a writer and future statesman—was observing the scene from across the bay. Many years later, this Pliny put down his reminiscence of the catastrophe in a couple letters to the historian Tacitus.

Here is what he said about the eruption:

A cloud, from which mountain was uncertain, at this distance (but it was found afterwards to come from Mount Vesuvius), was ascending, the appearance of which I cannot give you a more exact description than by likening it to that of a pine tree, for it shot up to a great height in the form of a very tall trunk…

And here is the younger Pliny’s moving description of the aftermath:

We had scarcely sat down when night came upon us, not such as we have seen when the sky is cloudy, or when there is no moon, but that of a room when it is shut up, and all the lights put out. You might hear the shrieks of women, the screams of children, and the shouts of men; some calling for their children, others for their parents, others for their husbands, and seeking to recognise each other by the voices that replied; one lamenting his own fate, another that of his family; some wishing to die, from the very fear of dying; some lifting their hands to the gods; but the greater part convinced that there were now no gods at all, and that the final endless night of which we have heard had come upon the world.

It is difficult to imagine something more terrifying—especially when you consider that Pompeians had only feeble oil lamps to use in the ashy darkness as they made their escape. We have unusually detailed knowledge of the victims, as they died almost instantaneously, and were then entombed under the ash. Later excavators would fill in the cavities left by these bodies (now decomposed) to make gruesome plaster casts of victims in their last, painful moments. Some were sheltering in homes or basements, while others were struck down as they fled, carrying some money and a few valuables.

In the weeks and months that followed, the site was visited by survivors and, most likely, looters, who came to retrieve the valuables left behind. There is clear evidence of post-eruption tunneling, and it is even possible that some skeletons in the site are actually would-be robbers, whose tunnels collapsed on them. But after that, the site slowly drifted from memory, laying mostly undisturbed for well over a thousand years. Aside from a few chance encounters, the site was only really re-discovered—and then excavated—in the 18th century, by the Spanish engineer Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre.

Excavation has continued right up to the present day, as significant sections of the city still remain buried in ash. Just three weeks ago, for example, the discovery of a Pompeian pub was announced. Since the city’s discovery, archaeologists and antiquarians have raced against time to preserve the site, as tourism, looting, vandalism, pollution, the Italian sun, the Mediterranean rain, and the slow knife of time do their damage. Pompeii is even battle-scarred: Allied forces dropped bombs on the ruins (presumably they missed their target), reducing many structures to rubble. The city just can’t catch a break.

But now we must go back to the beginning. Though Pompeii is now known as a quintessentially Roman site, one must remember that the Romans were comparative latecomers in antiquity. Before they conquered Italy and spread their Latin language, the peninsula was populated by a patchwork of peoples speaking different Italic languages, such as Etruscan and Umbrian. Here at Pompeii, the people spoke Oscan; and they had been living in Pompeii for centuries before the Romans arrived. Indeed, it was the Greeks who came first, integrating Pompeii into their network of trading ports. (At the time, the city of Pompeii was much closer to the coast; volcanic eruptions have extended the land many hundreds of meters out into the Mediterranean since then.) In an exhibition center, some artifacts from these bygone days—pottery, armor, weapons—were on display.

After centuries of being gradually pulled into the Roman orbit, and serving as a Roman ally, Pompeii officially became a Roman colony in 89 BCE. This meant that its residents were just as much citizens of Rome as the denizens of the capital city itself. By the time of its destruction, Latin was spoken in the streets, Roman gods and emperors were worshipped in the temples, and Roman laws were enforced in the land. But it is worth remembering that many other peoples—Oscans, Greeks, Etruscans, Samnites—contributed to the shape of the city, too.

But enough background. Let us explore the site itself.

Upon entering the front gate, you soon come upon the so-called Antiquario. This is a kind of miniature museum with all sorts of artifacts on display—coins, jewellry, urns, furniture. But the most memorable thing to see are four plaster casts of victims, their bodies curled and twisted in the moment of death. Nearby there is a cabinet displaying a few dozen of the human skulls found at the site (as well as one horse skull). It is a grim introduction to Pompeii. Later on, I peered into another storage area for these petrified corpses. The human tragedy of Pompeii is brought painfully to mind by these remains. But the most touching might be a dog, whose final agonizing moment is captured in vivid detail. It is hard to look at.

Most of the time, however, visiting Pompeii does not feel at all like visiting a macabre museum. Rather, you find yourself walking down cobblestone streets and wandering in and out of buildings. But the streets themselves are interesting enough. There are recognizable sidewalks that run along the street, just like today—though unlike today, in Pompeii the sidewalks are elevated high from the street. In fact, the sidewalks are so high off the ground that I actually ripped the crotch of my bluejeans stepping up onto it (luckily, the rip was invisible while I was standing). The probable explanation for this is that the streets easily flooded during a downpour, as the city lacked sewers. (The streets also probably smelled terrible, for the same reason.) I must also mention one of the niftiest features of the Pompeian streets: the stepping stones that allow the pedestrian to cross the street without descending, while also allowing wheeled vehicles to roll through the gaps in the rocks. That is elegant design.

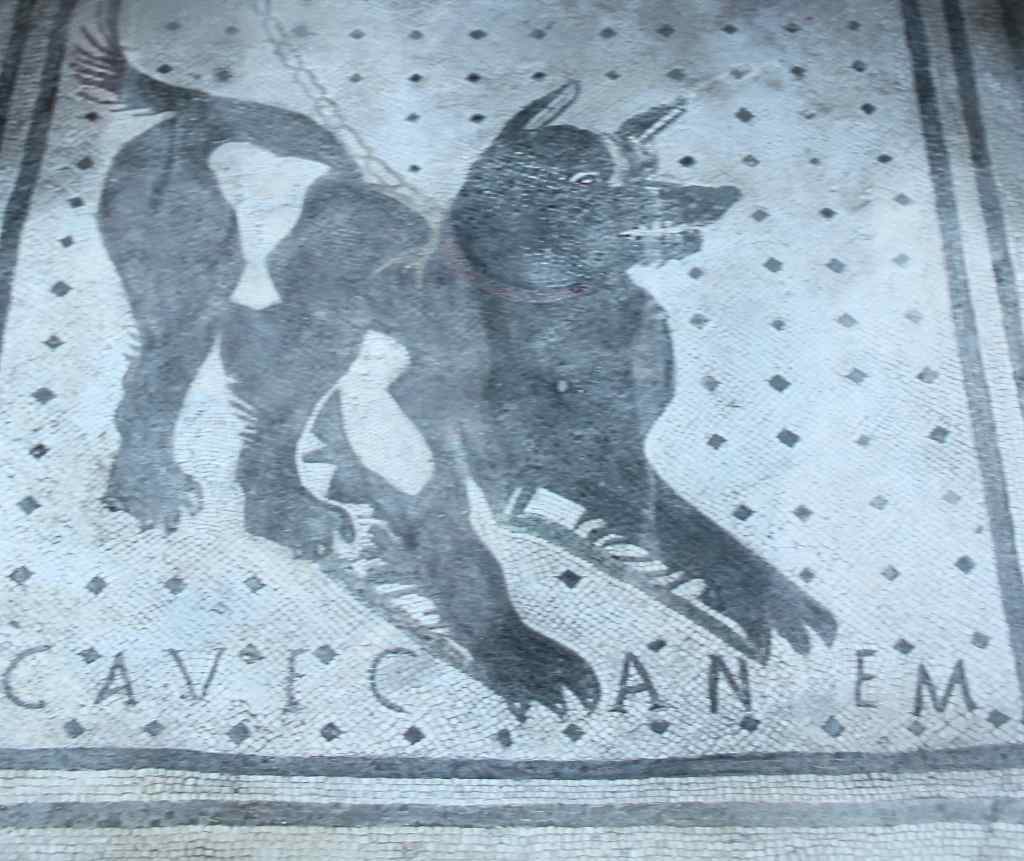

The buildings of Pompeii range in size, splendor, and state. Some are little more than a few walls and a roof, with weeds sprouting in the middle. But others are quite magnificent. Among the most famous is the so-called House of the Tragic Poet. We have no idea if a tragic poet really lived there; but the house has invited speculation because of the high-quality art packed into a relatively modest dwelling. More amusing to me, however, is the mosaic of a pooch on the floor near the entrance, with the words “Cave Canum” (“Beware of dog,” in Latin) spelled around it. Another notable residence is the House of the Faun—an enormous mansion, which obviously belonged to someone very wealthy, named after a charming little statue in its courtyard. The house was richly decorated. The Alexander Mosaic, for instance, adorned a floor here (imagine walking on such a work of art!). Above the doorway the word “HAVE” is inscribed, Latin for “Greetings”—though it does seem an unintentional pun on the owner’s wealth.

Another common sight in Pompeii are buildings with countertops, filled with large holes. At first, Holden and I speculated that they were communal toilets (which the Romans did use). In reality, however, these were eating establishments. Poorer residents, you see, usually lived in cramped little apartments on upper floors, with no kitchen and hardly any space to store food. Thus, unlike in our own day, it was the poor who ate out. The modern visitor can discover some erstwhile cooking implements, and even some frescos adorning the walls of these eateries—scenes of restaurant life (like two drunkards arguing) or images of what was on the menu: chicken, duck, goat. We know from surviving Roman cookbooks, as well as archaeological remains, that snails were a favorite. They were usually topped with garum, the ubiquitous Roman condiment made from fermented fish. Some garum was produced right in Pompeii, doubtless to the delight of neighbors’ noses.

(Competing with garum production for the stinkiest work in Pompeii was the fullery business, wherein workers—normally slaves—had to stand in a mixture of chemicals and urine, stomping on cloth, in order to soften it for garments.)

If you were a Roman with a little money and some free time, there were plenty of opportunities for entertainment. The biggest structure in the city was the Amphitheater, with seats for almost the entire town (20,000). Here, the bloodthirsty Roman citizen could enjoy a bit of ultra-violence—either in the form of gladiators hacking each other to bits, or humans and animals reducing one another to shreds. In a more pacific vein, Pink Floyd also had a concert here. For more sophisticated amusement, the Roman could head to the Theater Area, which contains two performance spaces, one large and one small, for plays and concerts. But one suspects that many Romans liked the Lupanar best of all—in plain English, the brothel. (“Lupanar” means “wolf-den,” which I suppose says something about the Roman attitude towards prostitution.) It was not especially difficult to identify this building as a brothel. There are erotic frescos adorning the walls, and hundreds of graffiti scratched on as well, mostly vulgar. It is a bit of a sad place, consisting of cramped rooms with concrete beds (one hopes they had mattresses).

The center of city life, as in all Roman settlements, was the forum. Nowadays there is not much to see—a collection of broken columns, supporting nothing, surrounding a big empty space. But one must imagine this place filled with all sorts of people, buying, selling, playing, laughing, and bickering. When I visited there was a statue of a centaur that I took to be original. Actually, it is a sculpture by Igor Mitoraj, a Polish artist, whose work was being exhibited throughout the site. I quite like it. Nearby are the Forum Baths, some of the best preserved Roman baths in existence. Bathing was quite important to the Romans; it was a communal activity, in a space where hierarchy mattered far less. Indeed, bath houses were public goods, owned by the state. Walking through this bath house, you can see the different spaces for hot, lukewarm, and cold baths. Though the image of squeaky clean, democratic Romans is appealing, Mary Beard reminds us that the water was not drained and refreshed. In other words, the Romans were probably bathing in a stew of bacteria and muck—if not worse.

The Romans were a rowdy and bawdy bunch, but they did have their more spiritual side. The city was littered with images of gods, both large and small; and several temples are to be found in the site. The best preserved of these is the Temple of Isis, captivating both for its well-preserved art and for serving as a window to how foreign gods were incorporated into the Roman pantheon. For Isis was, of course, an Egyptian goddess, and elements of Egyptian design are built into details of the temple. Nevertheless, it is a Roman construction, filled with Roman frescos quite non-Egyptian in style. For my part, I thought the temple was surprisingly small—a covered stone platform, accessed via a small stairwell—and I found the frescos a little silly. But for the women, slaves, and freedman who worshiped here (for Isis was a friend of the downtrodden), it must have been an awesome space.

Holden and I visited for about five hours before calling it quits. But we did not see all there was to see. Pompeii just has so much to offer. Indeed, I found it difficult even to wrap my mind around it. While I strolled through the ancient city, my thoughts were mostly blank, my emotions calm, as I wandered this way and that. But for days afterwards, I constantly thought about Pompeii. It is unlike any place I have ever visited, a startling journey to another time. There are plenty of more beautiful and impressive monuments—the Colosseum, the Roman forum, the Pantheon, the aqueduct of Segovia, the theater of Mérida—but no place comes close to the evocative power of Pompeii.

I like to think that a city is a concrete representation of the human mind. You can read our thoughts, values, and emotions in its buildings. In Pompeii you can observe the free and easy attitude towards sex and violence (in the amphitheater and brothel), the inequalities of wealth and status (in the different sized residences), but also the democratic ethos of the Roman people (in the baths). You note the importance of trade and commerce (in the forum), a spirit which even extended to the divine (if I sacrifice a goat to you, you have to reward me). The overwhelming impression is of an extroverted people. Every activity took place in public—eating, bathing, art, business, politics, and even defecation. Sex (or at least images of sex) was always in view. Like the Naples of today, then, Pompeii was a city that lived in its streets.

Epilogue

Holden and I returned to Naples by train. We were tired and footsore, but still eager to see more of the city. So in the remaining hour of daylight, we rushed to see the Castel Sant’Elmo. This is a castle situated atop the Vomero Hill, overlooking Naples. To get there without an exhausting climb, we opted to take the city’s funicular, a kind of subway for the slope. But lacking small change, we ended up climbing in without paying. Holden, to his credit, felt very bad about this. For my part, I was just eager to see the castle. Unfortunately for us, the place had closed right before we arrived, depriving us of the panoramic view of the city. This was the end of our sightseeing.

Now, I need to explain some details of our travel plan before going any further. Our flight back to Madrid left at an ungodly hour in the morning—around 5:30, if memory serves. So to save money, we had decided not to reserve our Airbnb for that night (since we would have had to leave at around 3:00 anyway) and instead sleep in the airport. Thus, now we had to retrieve our things from the Airbnb. After that we elected to have dinner in the same pizza restaurant as before. And it was even better this time. Italian families crowded around us, with children running around and grandparents clinking glasses. I felt fantastic.

After that, we slowly made our way through the center of town, on the way to the airport bus. On the way, we stopped to buy some gelato for dessert. It was some of the best ice cream I believe I have ever tasted; and it was served to me by an incredibly beautiful Neopolitan woman. The point is that I was feeling pretty great—relaxed, satisfied, my stomach full of pizza and ice cream. It was a great shock, therefore, when my jubilation was rudely interrupted at the bus stop.

We had missed the last airport bus, by just a few minutes. For no good reason, I had assumed the buses ran all night; but they stopped at around 22:30.

“I guess we gotta take a taxi,” I said to Holden.

“But wait,” he said. “Is the airport even open?”

“Open? Why not?”

But to double check, I looked it up on my phone.

He was right to ask: As I soon discovered, the Naples Airport closes from 23:30 to 3:30 every night. In short, we had nowhere to sleep and no place to go.

After a bit of despairing head-scratching, we came up with a plan. As it so happened, the Naples International Airport is not very far from the city center, only an hour and a half walk. If we walked slowly, we would arrive at around one or two in the morning, and then only have to wait a couple hours. Granted, we were both quite tired from having spent the day walking around Pompeii, but there did not seem to be much of a choice.

So we set out. The path soon took us out of the busy city center and into the bland and ugly outskirts. We passed twisting highways, empty parking lots, and suburban homes. After about twenty minutes, we happened upon a hostel. The light was on; and the reception room had a big, comfortable couch. I even smelled food. We asked how much it would cost to sleep on a bed for a couple hours, and were told thirty euros a piece. This was too much. Holden asked if we could just stay in the reception room for a while, but was denied. So we had to continue our way, through the suburb and into the industrial park surrounding the airport. Occasionally we passed a group of drunken youngsters; but for the most part the streets were deserted.

Eventually we arrived at a lot used for rental cars. It was fenced in; and next to the parking spots there was a vending machine with a couple benches.

“Let’s stop here for a bit,” Holden said. “I’m going to try to sleep.”

Holden lay down on a bench and, in minutes, was fast asleep. I tried to do the same. But I couldn’t relax. I felt cold and exposed, nervous that I was trespassing. Every time I was on the verge of sleep, a kind of high-pitched chirping would disturb me. Was it rats? I nervously looked around, wondering if the vermin were lurking under the cars. But I didn’t see anything. After a while I figured out that the sound was coming from the bats who were circling overhead, which made me feel at least a little better.

I was again trying to sleep when I heard a car approach. I looked up, and saw—to my horror—a car pulling into the parking lot. It pulled into a space and a man got out. He looked at me, and started walking in my direction. I panicked. Who was he, a police officer? I had no time to think. I got up and walked over to Holden, nudging him awake.

“Holden!”

“Huh? What?”

“Holden, there’s a guy!”

The next moment, he was standing before us. I opened my mouth to sleep. But before I could say anything, he smiled and started speaking in Italian. Judging from his expressions, he was telling us we were free to stay here. Then he gave us the thumb’s up, and left.

Whew.

We stayed there for another half hour or so, before we continued on to the airport. Even so, we arrived an hour before the doors opened. Nearby was a pod hotel, full of little sleeping capsules that can be rented by the hour. It was open; but by this time the price didn’t seem worth it. Besides, I was too nervous to sleep. Holden, for his part, took advantage of a plastic slide in the airport playground to catch a few more minutes of rest.

Finally, at 3:30 the airport doors opened, and we could escape the chilly night air. Soon we were flying back to Madrid, absolutely exhausted. Normally I don’t sleep well on planes; but I was basically comatose on that flight.

My trip to Naples thus ended with a little adventure. But even without this escapade, the trip would have been wonderfully memorable. Indeed, I feel as though every instant of my time there has stuck in my memory, and often catch myself daydreaming about the place. And though my visit could hardly have been more pleasant, I do have many regrets, as there is so much I did not see: Mt. Vesuvius, Herculaneum, or Posillipo in the surrounding area; and in the city itself, the Catacombs of San Gennaro, Underground Naples, or the Capella Sansevero. In short, Naples is an absolute joy, and I hope to return as soon as I can.