I made a podcast of my review of Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. You can listen here:

Month: July 2019

Memories of Sintra

There are many day trips that one can take from Lisbon, but one stands out both in popularity and importance: Sintra. This small city contains multitudes. Populated since prehistoric times, occupied by the Moors, used as a summer retreat by the royal family, and then beautified during the Romantic age of architecture—the city is bursting with monuments. And, most importantly, Sintra is easily accessible from Lisbon, merely a 45-minute ride on a cheap commuter train from Lisbon’s central Rossio station.

A penalty of this accessibility and attractiveness is, of course, popularity. The city is crawling with tourists and all of the concomitant junk: overpriced restaurants, tacky gift shops, crowded streets, and so on. But, of course, if Sintra is popular, it is popular for a reason. This is apparent as soon as you step off the train. The surrounding countryside is picturesque in the extreme, with rolling green hills dotted with tile-roofed houses. The old center of the city is just as lovely, filled with imposing mansions (Sintra has long been the wealthiest spot in Portugal) ranged along medieval streets.

The whole place has the aura of a fairytale, so it is fitting that Hans Christian Anderson visited in 1866. A plaque marks the house where he stayed. Lord Byron was another famous visitor, relishing the dark forests and the craggy peaks that loom above the city. When he first visited the city, he wrote “Oh Christ! it is a goodly sight to see / What heaven hath done for this delicious land! / What fruits of fragrance blush on every tree! / What goodly prospects o’er the hills expand!” Years later, in a famous line from Childe Harolde’s Pilgrimmage, Byron dubbed the place a “glorious Eden”—words that the Sintra tourist office are grateful for, I’m sure.

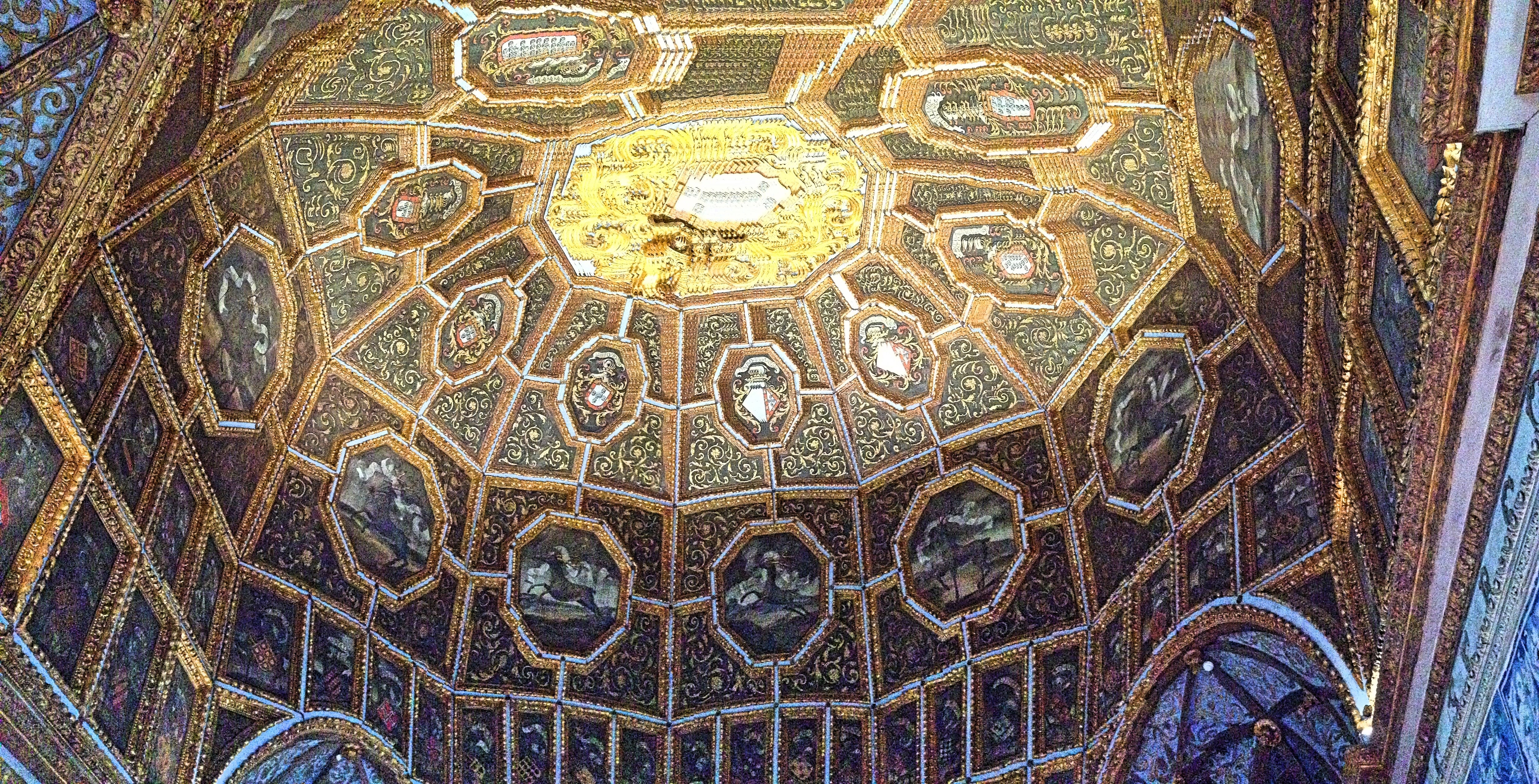

The most notable landmark within the old center is the Sintra National Palace. Compared with many other European palaces, this one has a rather modest aspect, striking the visitor as a large manor house rather than an imposing royal residence. Its most notable aspect are the two white cylindrical smokestacks that rise up from one side, like the two ears of a rabbit (used for the kitchen). The interior decoration, too, is quaint rather than majestic. Wood-paneled ceilings are decorated with the images of swans, magpies, and sailboats. The only room that is unmistakably regal is the Sala dos Brasões, or the Blazons Hall, with features a Moorish-influenced wooden ceiling bearing over seventy coats of arms of noble families, with azulejos running across the lower half. One is also reminded of Portugal’s Age of Exploration, since a delicately-carved model of a Chinese temple is also on display.

Most of Sintra’s notable monuments are, however, not to be found in the city center; rather, one must ascend the hill overlooking the old town. It is possible to walk up this hill, though it is not for the faint of heart. I think it would take at least an hour of trekking from the base to the top. Most people opt for the bus, specifically the 434 bus, which leaves from Sintra’s train station. Now, I have taken this bus up twice and it has been highly unpleasant both times. The road leading up is steep, winding, and narrow; it is easy to get stuck behind a slow driver. In any case, the bus is normally packed to bursting, so that one may have to stand up during the ride, gripping the railings for dear life as the bus chugs its way up.

The bus stops near two major monuments: the Castle of the Moors, and the National Palace of Pena. I opted for the former during my first visit, for the very silly and superficial reason that it was cheaper.

The Moors were no fools: when they built fortifications, they chose locations wisely. This is just such an example: the old castle sits atop a hill, providing great visibility of the surrounding area and making attack up the steep hill difficult. Nevertheless the castle fell, in the 12th century, to the invading Christians (though it was not taken by force). Henceforth it became a Christian castle, and was periodically rebuilt and reinforced down the years. The walls that stand today probably owe little to the Moors, the castle’s name notwithstanding.

It is an extremely romantic spot. Grey granite walls rise out of the trees, snaking around the hillside. The visitor can walk along these walls, enjoying the unsurpassable view of the surrounding countryside. Below one can see the town of Sintra itself, ensconced in the forest and centered around the palace, with the green countryside beyond speckled with habitations as the land spreads out until the blue sea in the far distance. Though the hill is not very high, standing atop the walls and looking down gives one an amazing sense of height. Aside from the view, the castle itself spurs the imagination. Its crumbling form, wrapping around little but empty forest, evokes a faraway time. Like all ruins, the fortification’s very incompleteness invites fantasy.

Standing on the walls, back in 2016, I could see across to the colorful, even disneylandish form of the National Palace of Pena. I was both intrigued and repulsed by what I took to by a terrific display of gaudiness. Yet despite this garish impression, enough curiosity formed deep within my psyche to prompt me to revisit Sintra, two years later, with the purpose of seeing this memorable building up close.

The Pena Palace was built in the 1800s, during the high point of architectural romanticism: and it remains a monument to this movement. Romanticism, as a movement, was characterized by a fascination for everything exotic and ancient. The Romantic imagination, no stickler for details, freely mixed elements of medieval France, Renaissance Europe, Golden-Age Portugal, and Moorish Spain, resulting in an eclectic jumble of styles held together by sheer exuberance. The castle today is dominated by its bright pallet of red, blue, and yellow—its flamboyant form visible for miles around.

When I spied the castle from the Castle of the Moors, it did not look very big to me—even smaller than the Sintra Palace below. Yet when I finally approached the building, years later, I found it to be gigantic, dwarfing all of the visitors that climbed up to visit. The palace has a roughly tripartite structure, with a red right, a blue center, and a yellow left. The visitor first passes through an elaborate stone gate, reminiscent of the Torre Belém, in order to reach the front entrance. There another gate—the walls covered in blue tiles, with elaborate and gruesome decorative sculptures surrounding the windows—leads inside the palace. From here I entered a sort of cloister, with every surface covered in tiles of blue, orange, and green, rather like those in the Alhambra.

Many of the rooms we passed were similarly decorated. The roofs, however, swelled into elaborate, web-like vaulting: a parody of gothic cathedrals. From within the cloister we could look up to see the bright red tower, whose form is also reminiscent of the Torre Belém. As is typical of palaces, there were rooms full of ornate furniture and other expensive decoration. In one room a beautiful candelabra with glass blown to look like leafy vines hung from the ceiling; in another, the Noble Room, nearly life-sized statues of bearded men held up the candles. Royalty has its rewards. Yet one of the more memorable rooms was the kitchen, whose elegant simplicity contrasted sharply with the pageantry above.

This strange architectural conglomeration owes its form to many hands. The primary architect was the German Wilhelm Ludwig von Eschwege, who is also remembered for his geological research. The King and Queen themselves also lent a hand in the decoration. As it stands today, the palace is somewhat reminiscent of the modernist works of the Catalan architects Gaudí and Domènech i Montaner, though it lacks the controlling intelligence that vivifies the works of those two men. The final impression not one of beauty, but of a kind of whimsical playfulness, strangely contrasting with the normally austere ideal of monarchy.

Eschwege also lent a hand in planning the gardens surrounding the palace, and in this he was highly successful. Both times I visited this hill, I decided that I could not endure another bus ride, and elected to walk down the hill. Luckily, gravity aids greatly in this direction. I recommend this strategy, since the forest is lovely. Here you can see the other layers of walls that form the Castle of the Moors, which slither down the mountain like a ridgeback snake. While lost in this forest, it is easy to see why this spot attracted the attention of romantics: the decaying ruins amid the tangle of trees perfectly evokes that sense of distant grandeur that so beguiled the romantic imagination.

I reached the end of the hill, continued further down through the old streets, once again admiring the many small, nameless corners of beauty in the city. As I got on the train back to Lisbon, I thought complacently that, finally, I had seen what Sintra had to offer. But I was mistaken—which I would have known if, for once, I had done some research before visiting. In fact, I had not even come close to exhausting the treasures of Sintra, so it seems that I must still go back.

The most famous thing I missed is the Quinta da Regaleira. This is yet another monument of the eclectic imagination of the romantic mind. A “quinta” is a large manor house, typically owned by an aristocrat of some sort. This one was eventually purchased by António Cavalho Monteiro, an eccentric who was lucky enough to inherit a large fortune. He used this fortune to create a landscape of mysteries. The dominant architectural style of this property is neo-gothic, which can be seen in the palace and the chapel. The gardens, however, reveal the previous owner’s love of the enigmatic: they feature several tunnels and even two inverted towers that Cavalho Monteiro dubbed “initiation wells.” They were apparently used in rituals related to Tarot cards. Nowadays they are used in the modern ritual of Instagram.

Nearby is the Quinta do Relógio, a Neo-Mudéjar manor house that is currently on sale for over $7,000,000. Tempting, I know. Also close is the Seteais Palace, a large manor house originally constructed for the Dutch consul in the 18th century, and now run as a luxury hotel. Probably outside my budget. Somewhat further off is yet another palace: the Montserrate Palace, which used to serve as a summer getaway for the court. This somewhat strange-looking edifice is yet another example of the romantic style of Sintra’s architecture: colorful, exotic, miscellaneous.

This short list only scratches the surface. Probably the best way to see everything is with a car and a few days to spare, not just a day-trip from Lisbon. I am sure that such a trip would be amply rewarding. The area is enchanting, and has enchanted so many people throughout the years that it is filled with monuments to its own charm. I can see what Lord Byron was talking about.

Memories of Lisbon

Lisbon was the very first place outside of Spain that I visited in Europe. It was in April of 2016, during Holy Week, as the end-point of a trip through Extremadura. We took a Blablacar, and I was amazed that there was no border, natural or artificial, between Spain and Portugal.

As we approached the city, the driver turned on the radio to let us hear Portuguese. I had hoped that my experience with Spanish would allow me to understand a little of this sister tongue. But it was absolutely foreign to my ears. Far from sounding like a closely-related language, Portuguese was as familiar as Russian. (I have since learned that this reaction is quite common. Peninsular Portuguese is strikingly different in pronunciation and speech rhythm from Spanish, even though on paper the two languages are quite similar.)

We entered the city on the majestic 25 de Abril Bridge—a suspension bridge conspicuously reminiscent of the Golden Gate Bridge of San Francisco. (The 25th of April, 1974, is the date of the famous Carnation Revolution, when the dictatorship was overthrown.) Two massive towers hold up a double-decker span over the river Tagus, the whole thing painted a rusty red color. Next to the bridge is another monument that recalls a foreign city: Christ the King, a tall statue of Jesus inspired by the famous Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro. Through the cables of the bridge we could see the city of Lisbon huddled on the riverbank, its colorful tiles shining in the sunlight. This was my first glimpse of the city.

(The Tagus, by the way, is the longest river in the Iberian Peninsula, also passing through Toledo and Aranjuez.)

Despite this grand entrance, however, my mood quickly turned sour. I had been spending the previous six months exploring Spain like a madman, slowly getting the lay of the land, coming to understand the ancient country’s geography, culture, and language. Now I was, once again, a complete novice. I did not have the slightest grasp of Portuguese, so I had to rely on English, which made me feel like any other tourist. (This wasn’t a problem for communication, since the Portuguese are excellent linguists.) And I had not even the slightest notion of the history of anything we saw.

But maybe this is all just an excuse. Maybe I was just sick of being on the road. After all, I had hardly spent a single weekend in Madrid the whole year. Whatever the cause, I managed to sabotage my own trip to Lisbon. I spent the better part of my time in that beautiful city wishing I were back in Spain. As anyone who has been to Lisbon knows, this is a shame, since Lisbon is one of the jewels of the Iberian peninsula—indeed, of all Europe.

Residual guilt and regret prompted me to revisit the city two years later, in September of 2018. TAP Portugal, the budget airline, lets you have a layover in Lisbon for no additional charge. So, before returning to Spain for the new school year, I had a little vacation in the Portuguese Capital, determined to see the city with fresh eyes. It was worth it.

Lisbon has one of the most distinctive profiles of any European city. The streets are paved with the famous Portuguese pavement—smooth bits of stone, black and white, that are sometimes arranged into mosaics. The buildings, meanwhile, are marked by that other distinctly Portuguese art: azulejos, or colored tiles. Even very ordinary apartment buildings are coated in shining porcelain. The city is generally quite hilly; and the smooth pavement does not make walking any easier. But the hills are what make Lisbon so dramatic, for streets will open up into magnificent views of the city and the ocean beyond.

On my first trip to Lisbon I learned something of the history and layout of the city by taking a “free” walking tour. The tour lasted four hours, and it was one of the most memorable experiences from my travels. We were led around by a man with long, flowing, black hair, whose passion for the city was intoxicating. He was a true Portuguese patriot, and an enthusiastic son of Lisbon. As he reminded us, Lisbon is one of the oldest cities on the Iberian Peninsula and indeed in the world, founded by the Phonecians and later occupied by the Carthaginians and the Romans. The city is far, far older than the country for which it serves as capital.

In our guide’s memorable phraseology, Lisbon is a woman—with “black, flowing hair” (like his) “studded with seashells, who wears a dress that flaps in the wind like a sail.” Her husband, he continued, was the sea; and their child is the neighborhood of Alfama. This is the oldest neighborhood in the city; and if you have an ear attuned to languages, you will know that its name derives from Arabic. Though popular with tourists, the neighborhood has preserved much of its original charm. When we arrived, neighbors were chatting through their windows, and an old woman was washing something in a fountain. The area preserves the chaotic jumble of narrow streets typical of ancient cities; and this arrangement muffles out much of the extraneous urban noise, giving the Alfama a peaceful atmosphere.

Our guide also took us to the Bairro Alto, the “upper district.” Indeed, the neighborhood stands on one of the city’s hills. It was built considerably after the Alfama, and its streets lack the labyrinthine intricacy of that lower zone. Nevertheless, the streets are intimate and at times reveal lovely views of the city. More importantly, the Bairro Alto is the center of Lisbon’s youth culture nightlife, comparable to Brooklyn or Madrid’s Malasaña. At night the streets are packed with crowds of drinkers freely mingling. Unfortunately I did not get a chance to partake.

I did, however, go to see a fado concert in a café in this neighborhood. Fado is the flamenco or the blues of Portugal: a folk music sung to the accompaniment of a guitar (in this case, a Portuguese guitar). Though I did not understand the words, the music’s mournful quality is palpable. As the guide of our free walking tour informed us, the music expresses saudade, a Portuguese word that means “longing”—a deep state of spiritual disquiet for something missing. Our guide, incidentally, thought that this feeling was at the heart of the Portuguese character: the yearning of a widow for her fisherman husband, lost at sea; or the urge that drove the Portuguese to push off into the unknown during the Age of Exploration; or nowadays the longing of some Portuguese (our guide among them) for the country’s Golden Age, when it was briefly one of the most powerful states on earth. Thus our tour ended with our guide stating his desire that Portugal leave the European Union to forge its own path. Quite an experience.

To continue with my overview of the city, we turn next to Baixa. It stands in the heart of the city, and at the heart of Baixa is the Plaça do Comécio. This is a grand, monumental square that opens up right to the River Tagus. An equestrian statue of Joseph I of Portugal stands at the center of the yellow buildings, with the king looking warlike and formidable despite being mainly dedicated to opera during his reign. In this area are to be found high-end shopping and touristy restaurants, which I like to avoid. Right next to Baixa is Chiado, a similar zone of shopping and restaurants, containing some of the city’s central plazas.

One of Lisbon’s most characteristic sights are the trolleys. As in San Francisco, the trolleys help pedestrians to traverse the steep hills of the city; and they have become a tourist attraction in their own right. The trams preserve a retro look, since the cars in use are still of the same rather diminutive size as when the system was built, in the 1870s. The most famous tram line is 28, which often ridden just for providing a good tour of the city. Our guide, however, warned us that it was wise to keep a sharp eye on one’s belongings, since the trolley is patrolled by pickpockets. I took a ride on the tram on my first trip—waiting nearly an hour on line to do so—and was, sadly, quite disappointed in the experience. I think walking provides a much better view of the city.

Lisbon has more recently taken on a strangely south Asian appearance, due to the spread of rickshaws catering to tourists. Again, I preferred to walk.

As befitting a seaside city of steep streets, Lisbon has many excellent lookout points. One is the Miradouro de Santa Luzia, near the Alfama, which offers an excellent view of the deep orange tiles of the rooftops and the pastel blues and pinks of the buildings. Lisbon has none of the brooding majesty of some Spanish cities; it is all light and air. The lookout point itself is a nice place to have a rest, with its tile benches and flowering trees. Right next door is the Miradour das Puertas do Sol—offering another superb view of the Alfama and the river beyond. The last time I went an enormous cruise ship was docked right in front of the old neighborhood. This cannot be good for maintaining its local atmosphere.

By continuing up the hill you will reach what is simultaneously one of the best views and the most impressive monuments of Lisbon: the Castelo de São Jorge. This medieval fortification is built upon the ancestral core of the city, where everybody from the Phoenicians to the Moors had their own forts. This is no surprise, of course, since the castle stands upon an easily defensible spot, controlling all the surrounding ground and providing an excellent view of the river as well. It is a superb spot.

What remains today is hardly more than a husk—the proud walls encircling little but trees and a few decaying ruins. But it is worth visiting for the commanding view alone, which becomes especially dramatic once you climb up to the top of the walls. The castle gardens are home to a handful of peacocks, which surprised me by appearing high up above my head, in the branches of a tree. I had no idea that peacocks were so agile. The castle also contains a small museum, showcasing some of the archaeological objects unearthed there—many examples of ceramics, as well as some ornamental Moorish tiles.

From the front of the castle, overlooking the city, the visitor can spot one of the other great lookout points of Lisbon: the Miradouro da Graça. Further up that same hill is the Miradouro da Senhora do Monte, a place frequented by sunset lovers and aspiring instagrammers. The city is nothing if not photogenic.

During my first visit to Lisbon I was very surprised by its cathedral, often called the Sé. I was used to seeing the massive gothic, barroque, and neoclassical constructions of Spanish cities. Lisbon’s cathedral seems downright humble by comparison. It was built during the Romanesque period, which necessarily limits its size (since the barrel vaults of Romanesque architecture require a narrow space). What is more, the church has been repeatedly buffeted by earthquakes, most notoriously the Lisbon Earthquake of 1755.

This earthquake was one of the deadliest and most destructive in history. It was a catastrophe. The earthquake struck in the morning of All Saints Day, when most people were in church—heavy stone buildings that were probably the worst place to be. A massive tsunami followed in the wake of the earthquake, and in the chaos a fire raged out of control. In the end, tens of thousands of people were killed and over three-fourths of the city’s buildings were in ruins. During the walking tour our guide pointed out the Carmo Convent, a convent that has been maintained in its ruined state as a memorial.

This disaster caused ripples in Europe’s culture as well as its surface. Many took it as a punishment from God, since it fell on a holy day. Voltaire, meanwhile, was dissuaded of the Leibnizian idea that we live in the best of all possible worlds. This led, among other things, to the writing of his most famous book: Candide. But before that philosophical tale, Voltaire published a poem on the event, condemning the idea that humans had somehow deserved it: “And can you then impute a sinful deed, / To babes who in their mothers’ bosoms bleed?” Rousseau responded vigorously against this poem, asserting that humanity deserved it by being corrupted by civilization. After all, if the people of Lisbon had been living in little hamlets, spread out thinly across the landscape, the casualties would have been small. But it did not take a Voltaire to see through this casuistical argument.

My second trip to Lisbon was vastly enhanced by visiting two of the city’s museums. The first was the very popular Museo Nacional do Azulejo, which celebrates the great Portuguese art of colored tiles. The museum is somewhat out of the way, located in what was previously a convent: Madre de Deus. But it is well worth the effort to get there.

The collection offers a bit of history on the tradition of azulejos. As you may have intuited, the word is a loanword from Arabic, specifically the word for “small polished stone.” Any visitor to the Alhambra will know that decorative tile had a strong tradition in the Moorish world, the art of geometric design driven by the prohibition on depicting human forms. Even today, many if not most azulejos contain either geometric or plant motifs. However, this is certainly not always the case. Azulejo altarpieces depicting Jesus, Mary, and the saints were on display. Other tiles portrayed scenes of history or of daily life, like the tapestries that hung in many royal dwellings.

The variety was astounding. From restrained blues and white to vibrant colors of every kind; from quaint flowers to designs created from mathematical algorithms; from plain squares to tiles with three dimensions—the museum showcased the scope of the artform. Just as impressive as the collection, however, was the building itself. The convent has many richly decorated rooms, with golden altars, coffered ceilings, and walls covered with paintings. In one of the more celebrated rooms, the choir, the entire space is ornamented with gilded woodwork encasing high-quality oil paintings.

Yet the most stunning work on display was the Panoramic View of Lisbon before the 1755 Earthquake. This sequence of tiles encircles the walls of a large room, providing a detailed sketch of the riverside of Lisbon as it existed before that calamity. The work was originally commissioned to decorate a palace, presumably to help a monarch keep track of his own domain. Even a superficial inspection of this work will impress the viewer with how much the city has changed since the earthquake. The old city is covered with religious architecture: churches, convents, monasteries—and now only a hint of this monumental majesty remains. This azulejo is likely the closest thing we have to a snapshot of the ruined Lisbon.

The next museum I visited was the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, which is somewhat misleadingly translated as the National Museum of Ancient Art (though the word “antiga” just means old, not “ancient,” and indeed hardly anything in the collection comes from ancient times). This is the largest museum in Lisbon and indeed Portugal; in fact it boasts one of the largest collections in Europe—or so they like to boast.

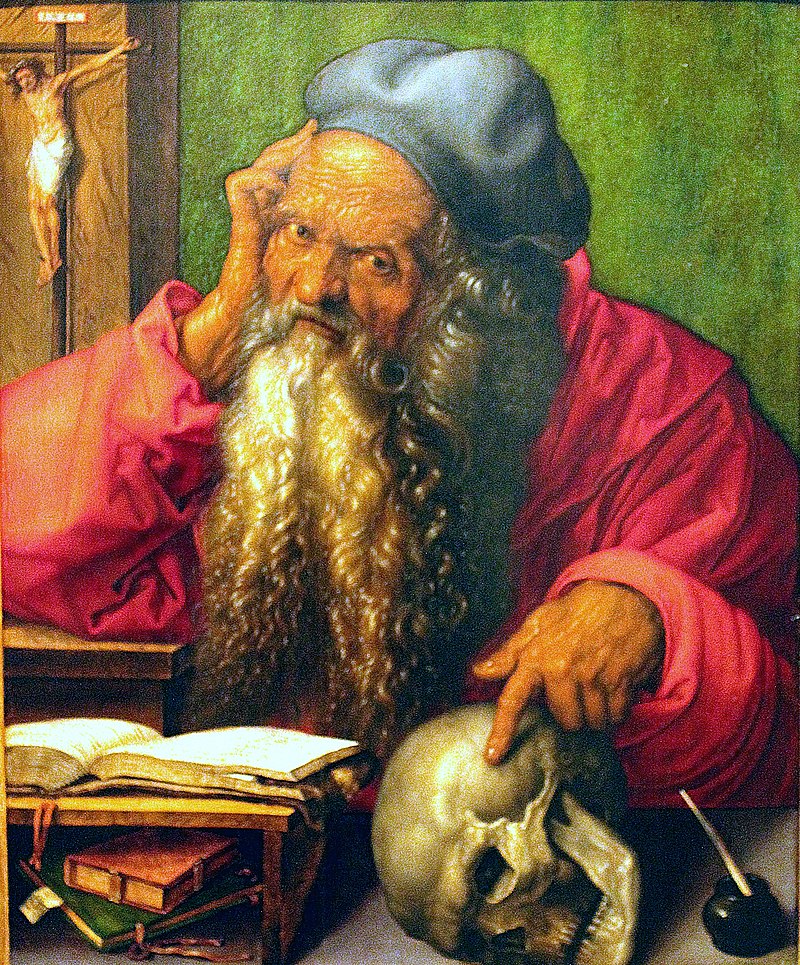

Judging from my visit, I am willing to believe the claim, for the museum seemed to constantly expand. Luckily, the museum is quite a pleasant space, since it is in an erstwhile palace. I first visited the painting gallery. It was far more impressive than I had anticipated. There were works by Dutch, German, Italian, and Spanish masters. I was particularly pleased to find a wry work by Albrecht Dürer, St. Jerome in His Study, with the old bearded saint pointing rather impishly to a skull as a memento mori. The airy, triumphant style of Giambattista Tiepolo (who decorated Madrid’s palace) was in attendance, as well as the dark, brooding style of José Ribera.

But my favorite work by a long shot was the Triptych of the Temptation of Saint Anthony by Hieronymous Bosch. Anthony was one of the early Christian ascetics, who isolated themselves in the desert in order to purify themselves. Bosch’s work represents the physical and spiritual temptations that the saint had to endure during his long years of fasting and prayer. As usual with Bosch, this gives rise to bizarre and fantastic imagery. The central panel is the main focus: showing the kneeling saint surrounded by the whole population of Bosch’s superfecund imagination: human-animal hybrids, men lacking limbs and even whole bodies, fish wearing armor, ruined buildings and burning cities—each of these images visually fantastic and symbolic of sin. It seems that Bosch had a both a horror and a fascination of sin, since he was so adept at portraying it.

Paintings constitute only a small part of the museum’s collection. There are all of the items of royal living: elegant furniture, finely-woven tapestries, delicately crafted silver and ceramic tableware—the list goes on. And the collection is not merely from Europe. Pioneering explorers and colonists as they were, the Portuguese collected many fine works from far off places, most notably China and (if memory serves) Japan. The museum’s sculpture collection is especially impressive, if only because of the way that the statues are arranged in the wide halls of the former palace, like silent servants waiting to be called upon.

Inevitably with a museum of this size, some version of fatigue sets in during the visit. Fortunately, the museum has a fine café which leads out to a garden in the back, where you can enjoy yet another sweeping view of the city. I would have lingered there longer, but the museum was closing and the guard kicked me out.

I have spent this long describing the enchanting city, but I have yet left out one of the most splendid corners of the city: Belém.

The name “Belém” is Portuguese for Bethlehem. The neighborhood stands rather far from the city center, near the mouth of the Tagus river. To get there it is best to take a tram or a train. I took the latter, passing under the 25 de Abril Bridge on the way.

I am afraid that my first trip to Belém, in 2016, only added to my bitterness at Lisbon. This is because the line to visit the Jerónimos Monastery—one of the famous monuments of the are—was very long; and after waiting for an hour and paying to get inside, I found out that the most impressive section of the monastery, the church, is free to visit and has no line at all. Let my experience serve as a warning to any visitors in a hurry.

All carping aside, the Jerónimos Monastery is by far the most impressive work of religious architecture in the city. Its size is immediately striking. Like so many grand monasteries, Jerónimos spreads out with the girth of a palace. While waiting in line, under the hot Portuguese sun, I did get a chance to admire the building’s beautiful façade: ornamented with fabulously intricate friezes designed by João de Castilho (or, as he is known in his native Spain, Juan de Castillo). The cloisters of the monastery are some of the finest I have ever seen, so delicately carved that it makes the stone seem lighter than air. Within this monastery are buried several Portuguese luminaries, such as the novelist Alexandre Herculano and the poet Fernando Pessoa.

The monastery church maintains this exquisite decoration. In the vast and gloomy space, culminating in web-like vaulting, the columns rise up like legs. Each of them has been carved almost from top to bottom. As in the Escorial Monastery in Spain, Jerónimos serves as the royal resting ground. Large pyramidal tombs sit upon sculpted elephants, containings kings and queens. Yet the most famous people buried in the church had not a drop of blue blood. In matching tombs near the entrance are buried Luís de Camões, Portugal’s greatest poet, and the famous explorer Vasco da Gama. These tombs were constructed long after those two eminent men died; but their remains were transported here in the 19th century.

The style that characterizes the Jerónimos Monastery is called Manueline—a blend of gothic, Italian, Spanish, and Moorish influences—and it is typical of the Portuguese Golden Age. Nearby is another excellent example of this style, as embodied in the Belém Tower. Indeed, this tower was composed of the same rock as was used to make the monastery. It was built as a defensive structure; but this pragmatic function did not lead to a dull edifice. Rather, the fortification displays the same exuberant decoration as the monastery. The fortress was originally constructed on a small island near the bank; but the shoreline has gradually expanded, so that nowadays the tower can be visited on foot. Both times I saw the tower, the line to enter was quite long, so I decided against it.

Just down the river from the tower is the Monument to the Discoveries. This is a far more recent construction, having been built in 1939 for the Portuguese World Exhibition. It is a worthy addition to the area. The massive concrete fin is shaped like the prow of a ship; and riding on top, in a heroic procession, are great figures from Portugal’s Age of Discovery. In the space in front of the monument, a large mosaic compass has been inserted into the pavement. In the center is a map of the world, with the names of notable explorers and the dates of their voyages marked. Most of the figures aboard the ship are, I am afraid, unknown to me. But at the tip is Henry the Navigator, the Prince who helped to inaugurate and coordinate the first Portuguese explorations.

No account of Belém would be complete without mention of the Fábrica de Pastéis de Belém, a bakery famous for making Lisbon’s most iconic food: pastel de nata. This is made with egg custard inside a small, crispy pie crust. They are omnipresent in Lisbon and make for an excellent breakfast or dessert. The recipe was originally developed in the Jerónimos Monastery itself, by monks who wanted to make some extra money. But when the monastery was secularized in the 19th century, the recipe was sold. While I am on the subject, I should also say that, in general, the food in Lisbon is quite good: fresh, flavorful, and reasonably priced. I especially enjoy the cod.

To sum up this long overdue account, Lisbon is a city of delights. The city itself is beautiful; and it is full of history and culture. Indeed, the only problem with Lisbon is that it is so nice that it attracts a great many tourists. But this is the curse of all great destinations.

Podcast Episode 6: Popper

For my next podcast, I recorded my review of Karl Popper’s Logic of Scientific Discovery.

You can listen here:

Review: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Reading this book was an illustration of the dangers of watching the movie first. I could not get Jack Nicholson out of my head, and heard all of the dialogue in his voice. This is, in part, a testament to the quality of the movie, which I think in many ways improved upon the book—both in plot and characterization. And though of course Kesey deserves credit for dreaming this whole thing up, I found his own version to be less compelling.

This is not an insult, however, since the movie is masterful and the book is almost as good. Both McMurphy and Nurse Ratched are iconic characters, and their clash is wonderfully realized. The list of strong secondary characters is too long to go through. As for plot, Kesey has managed to create a perfect parable for the countercultural narrative: that society cruelly forces people into conformity, and rebellious laughter and rule-breaking is the only way to stay sane and human.

All this being said, this is not simply a story about society in general. Now, I must preface these remarks by saying that I generally do not focus on issues of representation in novels. Not that representation is unimportant, but I think that literary merit is independent of social enlightenment. However, I think that the racism and misogyny in this book is so forward and so consistent that it cannot be passed over in silence. Indeed, I think that the issue of gender specifically was so strongly emphasized that it must have been an intentional choice on Kesey’s part, not an incidental attitude of an author from another time.

In short, all of the heroes of this book (aside from the narrator) are white men, and they are oppressed—in a bizarre mirror of real life—by black people and women. The narrator, Chief Bromden, fixates on the orderlies’ blackness, mentioning it at every point. They are the “black boys” with hands “big and black as a swamp” and faces of “slate.” They are rarely referred to by their names and never seen as fully human: just stupid soldiers for the hospital.

But I think that the misogyny runs deeper than the racism and is, indeed, one of the novel’s main themes. Kesey emphasizes it again and again. One of the most famous quotes from the book is: “Man, you lose your laugh you lose your footing.” But what is usually left out is what follows: “A man go around lettin’ a woman whup him down till he can’t laugh any more, and he loses one of the biggest edges he’s got on his side.”

Not to be too Freudian, but Nurse Ratched is the empodiment of the castration complex: a joyless, sexless woman intent on castrating the men. The idea of growing balls and having your balls taken away is repeatedly mentioned. In fact, one of the patients in the “disturbed” ward kills himself by cutting off his own testicles. When Nurse Ratched threatens to have McMurphy lobotomized, he jokes that she wants to cut off his nuts. And so on.

Nurse Ratched’s carefully concealed breasts are also one of the novel’s main metaphors: her attempt to be completely sexless is equivalent with her attempt to control the men and make them weak. McMurphy’s definitive revenge comes when he strips off the nurse’s uniform, exposing her breasts. She thus loses her power because “she could no longer conceal the fact that she was a woman.”

The drama of Billy Bibbit also falls into this pattern, and seems to indicate that, for Kesey, the proper relationship of men and women is for women to sleep with men, and that’s that. Bibbit is momentarily cured by finally getting laid (and the prostitutes are the only women portrayed positively) and is driven to desperation by the idea that his mother—another old, sexless woman—might find out. The entire reason that our hero, McMurphy, is committed in the first place is for statutory rape—a fact seen as heroic, not depraved.

Now, to repeat myself, this misogyny is so constant and so explicit that I do not think it is incidental to the book’s message. As Harding, the most articulate character, says: “We are victims of a matriarchy here, my friend, and the doctor is just as helpless against it as we are.” The whole story, then, becomes a kind of metaphor of the struggle of men to resist the enfeebling force of women: And social conformity itself is seen as primarily the doing of womankind.

I am unsure what to think about this. It is just possible that Kesey intended this as a kind of satire on misogyny, though the text did not read that way to me. In any case, despite this rather glaring theme, I still thought that the book was compelling. Kesey did, indeed, raise awareness for how psychiatric patients are mistreated. And the novel is undoubtedly a classic of the counterculture movement. The movie wisely toned down this prominent misogynistic aspect, which is yet another reason why I think it is superior.

View all my reviews

Podcast Episode 5: Ryle

My next podcast is my review of Gilbert Ryle’s The Concept of Mind.

You can listen to it here:

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/review-the-concept-of-mind/id1469809686?i=1000444804548

Podcast Episode 4: Wittgenstein

Episode 4 of my podcast is out. This one is my review of Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations.

You can listen to it here:

Podcast Episode 3: Heidegger

I made a postcast version of my Heidegger review. And I have a new microphone!

You can listen to it here:

Review: Heidegger’s Basic Writings

Basic Writings by Martin Heidegger

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Every valuing, even where it values positively, is a subjectivizing. It does not let things: be.

A Gentle Warning

In matters philosophical, it is wise to be skeptical of interpretations. An interpretation can be reasonable or unreasonable, interesting or uninteresting, compelling or uncompelling; but an interpretation, by its very nature, can never be false or true. Thus, we must be very careful when relying on secondary literature; for what is secondary literature but a collection of interpretations? Personally, I don’t like anybody to come between me and a philosopher. When a philosopher’s views are being explained to me, I feel as if I’m on the wrong end of a long game of telephone. Even if an interpreter is excellent—quoting extensively and making qualified assertions—his interpretation is, like all interpretations, an argument from authority; to interpret a text is to assert that one is an authority on the text, and thus should be believed.

Over generations, these interpretations can harden into dogmas; we are taught the “received interpretation” of a philosopher, and not the philosopher himself. This is dangerous; for, what makes a classic book classic, is that it can be read repeatedly—not just in one lifetime, but down the centuries—while continuing to yield new and interesting interpretations. In other words, a philosophical classic is a book that can be validly and compelling interpreted a huge number of ways. So if you subscribe to another person’s interpretation you are depriving the world of something invaluable: your own take on the matter.

In matters philosophical, I say that it is better to be stupid with one’s own stupidity, than smart with another’s smarts. To put the matter another way, to read a great book of philosophy is not, I think, like reading a science textbook; the goal is not simply to assimilate a certain body of knowledge, but to have a genuine encounter with the thinker. In this way, reading a great work of philosophy is much more like travelling someplace new: what matters is the experience of having been there, and not the snapshots you bring back from the trip. Even if you go someplace where you can’t speak the language, where you are continually baffled the whole time by strange customs and incomprehensible speech, it is more valuable than just sitting at home and reading guide books. So go and be baffled, I say!

This is all just a way of warning you not to take what I will say too seriously, for what I will offer is my own interpretation, my own guide-book, so to speak. I will make some assertions, but I’d like you to be very skeptical. After all, I’m just some dude on the internet.

An Attempt at a Way In

The best advice I’ve ever gotten in regard to Heidegger was in my previous job. My boss was a professor from Europe, a very well educated man, who naturally liked to talk about books with me. At around this time, I was reading Being and Time, and floundering. When I complained of the book’s difficulty, this is what he said:

“In the Anglophone tradition, they think of language as a tool for communication. But in the European tradition, they think of language as a tool to explore the world.” He said this last statement as he reached out his arm in front of him, as if grabbing at something far away, to make it clear what he meant.

Open one of Heidegger’s books, and you will be confronted with something strange. First is the language. He invents new words; and, more frustratingly, he uses old words in unfamiliar ways, often relying on obscure etymological connections and German puns. Even more frustrating is the way Heidegger does philosophy: he doesn’t make logical arguments, and he doesn’t give straightforward definitions for his terms. Why does he write like this? And how can a philosopher do philosophy without attempting to persuade the reader with arguments? You’re right to be skeptical; but, in this review, I will try to provide you with a way into Heidegger’s philosophy, so at least his compositional and intellectual decisions make sense, even if you disagree with them. Since Heidegger’s frustrating and exasperating language is extremely conspicuous, let us start there.

Imagine a continuum of attitudes towards language. On the far end, towards the left, is the scientific attitude. There, we find linguists talking of phonemes, morphemes, syntax; we find analytic philosophers talking about theories of meaning and reference. We see sentences being diagrammed; we hear researchers making logical arguments. Now, follow me to the middle of this continuum. Here is where most speech takes place. Here, language is totally transparent. We don’t think about it, we simply use it in our day to day lives. We argue, we order pizzas, we make excuses to our bosses, we tell jokes; and sometimes we write book reviews. Then, we get to the other end of the spectrum. This is the place where lyric poetry resides. Language is not here being used to catalogue knowledge, nor is it transparent; here, in fact, language is somehow mysterious, foreign, strange: we hear familiar words used in unfamiliar ways; rules of syntax and semantics are broken here; nothing is as it seems.

Now, what if I ask you, what attitude gets to the real essence, the real fundamentals of language? If you’re like me, you’d say the first attitude: the scientific attitude. It seems commonsensical to think that you understand language more deeply the more you rigorously study it; and one studies language by setting up abstract categories, such as ‘syntax’ and ‘phoneme’. But this is where Heidegger is in fundamental disagreement; for Heidegger believes that poetry reveals the essence of language. In his words: “Language itself is poetry in the essential sense.”

But isn’t this odd? Isn’t poetry a second or third level phenomenon? Doesn’t poetry presuppose the usual use of language, which itself presupposes the factual underpinning of language investigated by science? In trying to understand why Heidegger might think this, we are led to his conception of truth.

If you are like me, you have a commonsense understanding of what makes a statement true or false. A statement is “true” if it corresponds to something in reality; if I say “the glass is on the table,” it is only true if the glass really is on the table. Heidegger thinks this is entirely wrong; and in place of this conception of truth, Heidegger proposes the Greek word “aletheia,” which he defines as “unconcealment,” or “letting things reveal themselves as themselves.”

It’s hard to describe what this means abstractly, so let me give you an example. Let’s say you are a peasant, and a rich nobleman just invited you to his house. You get lost, and wander into a room. It is filled with strange objects that you’ve never seen before. You pick something up from a table. You hold it in your hands, entranced by the strange shape, the odd colors, the weird noises it omits. You are totally lost in contemplation of the object, when suddenly the nobleman waltzes into the room and says “Oh, I see you’ve found my watch.” According to Heidegger, what the nobleman just did was to cover up the watch in a kind of veneer of obviousness. It is simply a watch, he says, just one among many of its kind, and therefore obvious. The peasant, meanwhile, was experiencing the object as an object, and letting it reveal itself to him.

This kind of patina of familiarity is, for Heidegger, what prevents us from engaging in serious thinking. This is why Heidegger spends so much time talking about the dangers of conformity, and also why he is ambivalent about the scientific project: for what is science but the attempt to make what is not obvious, obvious? To bring the unfamiliar into the realm of familiarity? Heidegger thinks that this feeling of unfamiliarity is, on the contrary, the really valuable thing; and this is why Heidegger talks about moods—such as anxiety, which, he says, discloses the “Nothing.” Now, it is a favorite criticism of some philosophers to dismiss Heidegger as foolish by treating “Nothing” as something; but this misses his point. When Heidegger is talking of anxiety as the mood that discloses the “Nothing” to us, he means that our mood of anxiety is the subrational realization of the bizarreness of existence. That is, our anxiety is the way that the question faces us: “Why is there something rather than nothing?”

This leads us quite naturally to Heidegger’s most emblematic question, the question of Being: what does it mean to be? Heidegger contends that this question has been lost to history. But has it? Philosophers have been discussing metaphysics for millennia. We have idealism, materialism, monism, monadism—aren’t these answers to the question of Being? No, Heidegger says, and for the following reason. When one asserts, for example, that everything is matter, one is asserting that everything is, at base, one type of thing. But the question of Being cannot be answered by pointing to a specific type of being; so we can’t answer the question, “what does it mean to be?” by saying “everything is mind,” or “everything is matter,” since that misses the point. What does it mean to be at all?

So now we have to circle back to Heidegger’s conception of truth. If you are operating with the commonsense idea of truth as correspondence, you will quite naturally say: “The question of ‘Being’ is meaningless; ‘Being’ is the most empty of categories; you can’t give any further analysis to what it ‘means’ to exist.” In terms of correspondence, this is quite true; for how can any statement correspond with the answer to that question? A statement can only correspond to a state of affairs; it cannot correspond to the “stateness” of affairs: that’s meaningless. However, if you are thinking of truth along Heidegger’s lines, the question becomes more sensible; for what Heidegger is really asking is “How can we have an original encounter with Being? How can I experience what it means to exist? How can I let the truth of existence open itself up to me?”

To do this, Heidegger attempts to peel back the layers of familiarity that, he feels, prevents this genuine encounter from happening. He tries to strip away our most basic commonsense notions: true vs. false, subject vs. object, opinion vs. fact, and virtually any other you can name. In so doing, Heidegger tries to come up with ways of speaking that do not presuppose these categories. So in struggling through his works, you are undergoing a kind of therapy to rid yourself of your preconceptions, in order to look at the world anew. In his words: “What is strange in the thinking of Being is its simplicity. Precisely this keeps us from it. For we look for thinking—which has its world-historical prestige under the name “philosophy”—in the form of the unusual, which is accessible only to initiates.”

What on earth are we to make of all this? Is this philosophy or mystical poetry? Is it nonsense? That’s a tough question. If by “philosophy” we mean the examination of certain traditional questions, such as those of metaphysics and epistemology, then it might be fair to say that Heidegger wasn’t a philosopher—at least, not exactly. But if by “philosophy” we mean thinking for the sake of thinking, then Heidegger is a consummate philosopher; for, in a sense, this is the point of his whole project: to get us to question everything we take for granted, and to rethink the world with fresh minds.

So should we accept Heidegger’s philosophy? Should we believe him? And what does it even mean to “believe” somebody who purposely doesn’t make assertions or construct arguments? Is this acceptable in a thinker? Well, I can’t speak for you, but I don’t accept his picture of the world. To sum up my disagreement with Heidegger as pithily as possible, I disagree with him when he says: “Ontology is only possible as phenomenology.” On the contrary, I do not think that ontology necessarily has anything to do with phenomenology; in other words, I don’t think that our experiences of the world necessarily disclose the world in a fundamental way. For example, Heidegger thinks that everyday sounds are more basic than abstract acoustical signals, and he argues this position like so:

We never really first perceive a throng of sensations, e.g., tones and noises, in the appearance of things—as this thing-concept alleges; rather we hear the storm whistling in the chimney, we hear the three-motored plane, we hear the Mercedes in immediate distinction from the Volkswagen. Much closer to us than all sensations are the things themselves. We hear the door shut in the house and never hear acoustical sensations or even mere sounds. In order to hear a bare sound we have to listen away from things, divert our ear from them, i.e., listen abstractly.

To Heidegger, the very fact that we perceive sounds this way implies that this is more fundamental. But I cannot accept this. Hearing “first” the door shut is only a fact of our perception; it does not tell us anything about how our brains process auditory signals, nor what sound is, for that matter. This is why I am a firm believer in science, because it seems that the universe doesn’t give up its secrets lightly, but must be probed and prodded! When we leave nature to reveal itself to us, we aren’t left with much.

And it was clear that I’m not a Heideggerian from my introduction. As the opening quote shows, he was partly remonstrating against our dichotomy of subjective opinion vs. objective fact; whereas this notion is the very one I began my review with. You’ve been hoodwinked from the start, dear reader; for by acknowledging that this is just one opinion among many, you have, willingly or unwillingly, disagreed with Heidegger.

So was reading Heidegger a waste of time for me? If I disagree with him on almost everything, what did I gain from reading him? Well, for one thing, as a phenomenologist pure and simple, Heidegger is excellent; he gets to the bottom of our experience of the world in a way way few thinkers can. What’s more, even if we reject his ontology, many of Heidegger’s points are interesting as pure cultural criticism; by digging down deep into many of our preconceptions, Heidegger manages to reveal some major biases and assumptions we make in our daily lives. But the most valuable part of Heidegger is that he makes you think: agree or disagree, if you decide he is a loony or a genius, he will make you think, and that is invaluable.

So, to bring this review around to this volume, I warmly push it into your hands. Here is an excellent introduction to the work and thought of an original mind—much less imposing than Being and Time. I must confess that I was pummeled by Heidegger’s first book—I was beaten senseless. This book was, by contrast, often pleasant reading. It seems that Heidegger jettisoned a lot of his jargon later in life; he even occasionally comes close to being lucid and graceful. I especially admire “The Origin of the Work of Art.” I think it’s easily one of the greatest reflections on art that I’ve had the good fortune to read.

I think it’s only fair to give Heidegger the last word:

… if man is to find his way once again into the nearness of Being he must first learn to exist in the nameless. In the same way he must recognize the seductions of the public realm as well as the impotence of the private. Before he speaks man must first let himself be claimed again by Being, taking the risk that under this claim he will seldom have much to say.

Review: Père Goriot

Père Goriot by Honoré de Balzac

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Money is life; money accomplishes everything.

I recently worked as a slush pile reader for a literary magazine, sorting out the best stories from the flurry of submissions. Many of these were quite expertly written—sharp prose, snappy beginnings, intriguing plots, quirky characters, and all of the other boxes ticked. However, the lion’s share lacked something which I came to call “weight.”

The stories never escaped the sense of airy insubstantiality that besets much fiction, that nagging and persistent sense of emptiness—in short, of being entirely fiction. The characters spoke with the voices of puppets and moved in a daydream world. I could not believe, so I did not care. Balzac presents a striking contrast. From the very start, this novel is heavy-laden with realistic details snatched from history and from daily life. Far from being phantasmagoric, the setting is etched into the memory with acid, becoming more real than the characters themselves.

Doubtless this ability to lend the weight of reality to his stories is what made Balzac the father of realism. But Balzac’s realism is most impressive in his depiction of the Paris of the Bourbon restoration; it does not extend so forcefully to his characters. Even the best characters in this book are rather one-dimensional and static; they achieve force through intensity, not complexity. Balzac endows each of his creations with an overwhelming passion, a monomania. In the case of Goriot it is his daughters; with Rastignac, social clout; and with Vautrin, a general diabolical glee.

But if Balzac does not stop at these monomanias, for he is at pains to show that each of these passions is fundamentally rooted in money. Goriot loses the affection of his daughters by giving away his last bit of money; Rastignac realizes that money is the key to social success; and Vautrin wishes to buy a plantation in the American south. For a nineteenth-century novel, this is refreshing. Balzac eschews the usual plot mechanics of romance and marriage in favor of the far more contemporary problem of making one’s way in a morally treacherous world. He is a genius at revealing how mercenary motives worm their way into even the most intimate of relationships.

Given Balzac’s reputation for realism, I was surprised by the amount of melodramatic passion on display in this novel. Often this was a weakness, loading the book down with declamations and hysterics. But, at times, it allowed Balzac to reach a level of emotional intensity that was almost operatic. This was particularly true in the final scene, where the combination of grinding poverty, total desperation, and feverish despair reached Dostoyevskian proportions. Indeed, Pere Goriot was a major influence on Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, as is clear from the many parallels between the two books.

The final result is a book which, if aesthetically rough and conceptually limited, is both an incisive look at the hypocrisies of society and a gripping work of art.

View all my reviews