Columbus: The Four Voyages by Laurence Bergreen

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I remember learning about Columbus when I was in elementary school. The story was simple: he was a daring, visionary man who set out to prove that the earth was round, heroically defeating the nay-sayers who thought that he would sail right over the edge of the earth. To the mind of a child, it is a compelling tale. It is also, of course, complete fantasy (to use a polite word). Since those Edenic days of unproblematic national heroes, Columbus has become a much more divisive figure. So I decided I ought to get the real story, hopefully from somebody without an ideological axe to grind.

As I knew from his books on Marco Polo and Magellan, Bergreen is in the business of writing popular histories of famous explorers. This book is up to his usual standards, though the raw material he had to work with is naturally somewhat messier. Both Polo and Magellan were famous for one iconic voyage, while Columbus travelled to the “New World” on four separate occasions. Instead of one grand adventure, then, we get a series of expeditions, each one drearier than the last. By the fourth voyage, I was quite ready to be done with the Genoese explorer.

But I did learn. For example, Bergreen makes it clear that the competing narratives of Columbus have existed from almost the very beginning. There were rumors and accusations regarding his cruelty and incompetence during his lifetime (which resulted in his imprisonment); and not long after his death the great Spanish anti-colonialist, Bartolomé de las Casas, skewered Columbus for his role in the destruction of the native peoples. In short, he was never a universally beloved hero.

Furthermore, Columbus only became a cornerstone of patriotic ideology centuries later. He started to be celebrated in North America, for example, after the Revolutionary War, as the young nation searched for a founding myth that wasn’t so tied to England. In Spain, October 12th (when Columbus “discovered” the New World) did not become a holiday until 1892, as part of the conservative restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. In the United States, it was not made a holiday until 1937.

So, should Columbus Day be celebrated? Insofar as celebrating Columbus is merely a way of celebrating European colonization of the Americas (which certainly seems to be the case), then I think the answer must be a clear no. I don’t think it is possible to learn about the cataclysm that engulfed the native peoples of the Americas—which resulted in millions dead and the disappearance of so many cultures and languages—and think that worth celebrating. Granted, there is a kind of paradox for European Americans in this, since if there had not been a Columbus we would not exist; and it is difficult to wish oneself out of existence. Even so, celebrating the enslavement and elimination of whole peoples does not seem quite right.

Yet what about celebrating Columbus himself? Well, he does not exactly make a good impression in these pages. Certainly he was a bold and determined man, willing to risk his life for an idea (as well as for gold and glory). And his talent as a navigator is impressive. But these positive qualities seem rather pale when compared with his narrow-mindedness, his incompetence as an administrator, his cruelty to others, and his messiah complex. In the course of these voyages he combats several mutinies (with varying degrees of success), strands his own men (to be used as a bargaining chip), and has untold numbers of people enslaved. And even if you focus exclusively on his role as a “discoverer,” it is difficult to celebrate a man who steadfastly refused to acknowledge the truth of what he, in fact, had stumbled upon.

The truth is that Columbus, contrary to what the legend says, did not have a more accurate notion of the earth than the experts of the time. Precisely the reverse: Columbus’s voyage was based on a profound underestimate of the size of the earth. Indeed, it was pure luck that there was an unsuspected continent in the middle of the ocean. If America did not exist, and there were nothing but open sea between Europe and Asia—as he thought—Columbus would almost certainly have died in the enormous expanse of water. And he never even had the good grace to admit his mistake, insisting to the end that he had found a route to Asia, despite the very clear evidence to the contrary.

Of course, the fact remains that Columbus thought to do something that nobody (to his knowledge) had ever done before, and in the process inaugurated a new period of history. Indeed, given the tremendous importance of his voyage, we ought to do our best to understand both the man and the colonial undertaking he stands for. And I don’t think that is accomplished with myths and unreflecting celebration.

View all my reviews

Month: October 2023

Aachen: City of Charlemagne

It was the summer of 2022 and Europe was in the midst of an energy crisis. As a response to the rise in fuel prices, many governments attempted to make public transportation cheaper. Spain, for example, reduced the price of monthly metro cards by half and offered free train passes for commuters. Germany, meanwhile, offered a nine euro monthly pass that was valid for the bus, metro, and commuter trains for the entire country. It was an incredible deal, and I had arrived in Germany right in time to take advantage of it.

Now, this may come as a surprise if you believe in the German stereotype of efficiency and timeliness, but the trains in Germany are a mess, with constant cancellations and delays. (This is partly because, unlike in Spain or France, the high speed trains in Germany use the same tracks as the local trains.) The new 9-euro pass had only added to the chaos, since the added passengers put additional pressure on the already overburdened system.

So the train ride was not exactly quick. But I was in a good mood, nevertheless. You see, Aachen had been on my list for years, ever since I watched Kenneth Clark’s magnificent documentary Civilisation. The first episode of that series begins with the so-called Dark Ages, and culminates in the rise of Charlemagne—an event which, for Clark, signifies the rebirth of European civilization from the brink of destruction. Though many historians would, I think, dispute this dramatic conclusion, it cannot be denied that Charlemagne is a figure of paramount importance in the history of Europe. And if you want to learn about Charlemagne, Aachen is the place to be.

But my arrival was something of an anticlimax. As it happened, my train pulled into the Aachen Hauptbahnhof at almost the same moment that several appointments were made available on the Spanish government website. As I was in desperate need of an appointment (in order to get a document that would allow me to travel back to the United States while my visa was being renewed), I spent a panicked 15 minutes navigating the poorly designed and unreliable website in order to secure myself a spot. After so many years in Spain, I still feel acute and almost crippling anxiety when I have to do anything regarding my visa. My hands literally shook as I confirmed the appointment. When I realized I had been successful, relief washed over me.

Now, I could explore the town with no distractions. My route took me to one of the two surviving medieval gates of the city, the Marschiertor. (On the other side of town is the even more impressive Ponttor.) Nowadays, this huge gate stands alone, as Aachen is happily safe from foreign invaders—for the foreseeable future, at least.

Speaking of invasions, Aachen has been under the control of France on at least two occasions. First, it was ceded to France for about 15 years after Napoleon defeated the Holy Roman Empire. Then, after World War I, it was controlled by the allies until 1930. Germany lost control of the city at least once more after that, to American troops, who virtually leveled the place in the process. It was the first German city to fall to the Allies during the Second World War.

As you can see from these snapshots of its long and somewhat turbulent history, Aachen is not the sleepy town that is status as a spa city would have you believe (its hot springs have been appreciated since Roman times). Partially this is due to its history as a capital of the Holy Roman Empire (of that, more below). But this is also because Aachen is near the borders of Belgium and the Netherlands, making it simultaneously the door to Germany (in the Second World War) and, via Belgium, the door to France (in the First).

All this has resulted in a multitude of names for this place. In German it is, of course, Aachen, while in French it is Aix-la-Chapelle. Meanwhile, in Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish, the city is called some variation of Aquisgrán. This is an awful lot of historical and linguistic weight for one town of a quarter of a million souls to bear. But, on that sunny summer day, none of the residents seemed to notice or mind.

My first stop was the Aachen Town Hall. This is a venerable old building that, like Aachen itself, has suffered many reversals of fortune—burned down, left to crumble, burned down again, and then finally bombed. As it stands today, it is an imposing neo-gothic structure that looks more like the abode of a nefarious count than a civic-minded mayor. But the flocks of school children on field trips, and the wedding party out front, showed that—appearances to the contrary—this is indeed a beloved part of the town. For a modest price, you can even visit the interior of the Rathaus. If for nothing else, this is worth it to see the extremely well-made replicas of the Imperial Regalia of the Holy Roman Empire. (The originals are now in Vienna.) This includes the famous Imperial Crown, which is so encrusted with jewels that it looks decidedly uncomfortable.

My next destination was the Aachen Cathedral. This is by far the most famous sight in the city—the church built by Charlemagne himself, where 31 kings and 12 queens were crowned, one of the first places to be listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site. I walked in and was immediately awe-struck. But my amazement turned to confusion when I failed to find the legendary Throne of Charlemagne. I asked one of the tired-looking guards, in the best German I could muster, “Wo ist der Thron des Karl der Grosse?” He responded quickly, repeating the word “Führing” several times, which my dictionary told me meant “guided tour.”

With this new information, I left the cathedral and found the neighboring office, where tickets can be bought for the guided tour. Once there, I noticed an option to buy a combination ticket for the tour and the cathedral treasury—which worked out quite well for me, as it gave me something to do while I waited for the tour to begin.

Now, I have been in many cathedral treasuries by now, and most of the time I find them rather uninspiring—usually consisting of gold and silver reliquaries of various shapes and designs. But the artwork on display here was exquisite and unique. There is, for example, the Proserpina sarcophagus. Made of marble and carved in ancient Rome, it was brought here as a symbol of imperial rule by Charlemagne, who was quite possibly buried in it. Also (potentially) belonging to Charlemagne is a hunting horn and knife. But two works of the goldsmith stood out to me as the jewels of the collection.

One is the Cross of Lothair, made around the year 1000. On one side the gold cross is completely covered in jewels (much like the imperial crown). Strangely, in the very center of the cross is a cameo of Augustus Caesar. Now, it is possible that this pagan emperor was included to symbolize the connection between the ancient empire and the medieval so-called Holy Roman Empire. But it is just as possible that they simply did not know who it represented and thought it was a holy figure. In any case, the reverse side is certainly pious. Delicately engraved into the gold is a portrayal of the crucifixion. To modern eyes, it appears rather standard in design, if well-executed. But in 1000 the image of Christ suffering on the cross still wasn’t paramount in Christian decoration (notice the many depictions of Christ of the Last Judgments in medieval churches). This crucifix, then, is not only beautiful but artistically daring.

The other is the bust of Charlemagne, a reliquary containing a part of the king’s skull. Roughly life-sized, the bust was made hundreds of years after Charlemagne’s death, and so probably bears little resemblance to the actual king. But this portrait, however idealized, is shockingly lifelike nevertheless. The anonymous craftsmen who made it were obviously masters of their arts. The bust works on three levels, as a work of art, a religious object, and a symbol of imperial power. For example, the king’s tunic is covered with the imperial eagle and he wears a crown covered with jewels and, again, ancient Roman cameos (signifying the inheritance of the Roman Empire). It is a marvelous statue—delicate and beautiful, while authentically royal and imposing.

Now it was time to visit the cathedral. The visit began with the traditional entrance to the church, the Wolfstür. This is the subject of a legend, which (if memory serves) goes like this: The townspeople, lacking the time and resources to complete the church, made a deal with Satan. If he completed the church, he would be able to keep the soul of the first creature that entered its doors. But when it came time to honor the bargain, the townspeople craftily sent a wolf to enter the church doors, which is obviously not what Lucifer had in mind. The enraged devil tried to leave the church to punish the townspeople, but got his thumb caught in the closing door.

This story (repeated, in various forms, all over Europe and perhaps the world) has some physical manifestations. In the bronze door knocker, for example, there is a bump inside the lion’s mouth, which legend says is the satanic thumb. Once inside, there is a statue of the unfortunate wolf, and opposite that is (for whatever reason) a pine cone.

Finally we entered the church itself. The core of the structure—the so-called Palatine Chapel—goes back all the way to the year 800, though it has been so finely refurbished that you would hardly guess its age from its polished and immaculate appearance. In structure it is hardly like the typical European church, with its three names culminating in a main altar. Instead, the church is octagonal, with no natural front and back. It takes this design from the Byzantines, as the core of the church is closely modeled after Basilica San Vitale in Ravenna. Indeed, the structure even incorporates ancient marble columns taken from Rome. Clearly, Charlemagne was quite consciously forging a connection between his new kingdom and the splendor of the ancient world.

Hanging in the center of this splendid octagon is the so-called Barbarossa Chandelier, named for the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I (who had a red beard). Looking like a giant crown, its symmetrical shape complements the octagonal space, creating a sort of tunnel view up to the mosaic on top of the cathedral.

Then, our guide took out a large key and opened the grated metal door leading up to the stairs. This was the moment I had been waiting for, as I knew that Charlemagne’s Throne was on the up there. After pausing to admire the railings, ceiling mosaics, and marble columns, we arrived at the legendary seat.

It is, at first glance, almost comically unimpressive. Far from being the gold and bejeweled seat one might expect, it is made of plain stone slabs, sitting on a platform of what appear to be cinder blocks. Apparently, however, the slabs which make up the throne are relics of some kind (there are different theories, but they all connect the stones to Jerusalem and the life of Jesus). This contrives to make the throne itself into a kind of relic. And, indeed, visiting pilgrims would crawl underneath the throne as an act of devotion.

Considering this religious nature, “throne” may not even be the best word to describe this esteemed seat—at least, as it was originally conceived. Charlemagne, for example, was not crowned here, but in Rome. And, certainly, it is strange to imagine that ruler issuing his decrees from the second floor of a cathedral. But it became a throne, if it was not one to begin with. As I mentioned, dozens of monarchs were crowned on this very spot. Napoleon, in a rare moment of humility, climbed the steps but refrained from sitting down himself. According to our guide, such scruples did not stop Heinrich Himmler.

Now it was time to enter the gothic church. The original Palatine Chapel has, you see, been supplemented with a gothic choir, of a much more conventional—not to say unattractive—design. This part of the church also has its share of famous objects. There is, for example, Henry’s Pulpit (also called an “ambon”), which is yet another example of the golden and encrusted style typical of the Carolingian period. It is covered with exquisite ivory carvings and, as typical of the Holy Roman Empire, it incorporates elements of pagan art pillaged from Italy and the Holy Land. Nearby are the Karlsschrein and the Marienschrein, two enormous gold reliquaries. The first contains the bones of Charlemagne himself (moved from the Roman sarcophagus, apparently), while the second is supposed to contain Jesus’ swaddling clothes and a dress belonging to the Virgin Mary. What is indisputable, however, is that these two are remarkable examples of medieval metalworking.

This is where the tour ended. Dazzled, I wandered back into the streets of Aachen. It had warmed up by now and my jacket was unnecessary. Extremely hungry, I was gratified to find a German sausage restaurant right around the corner. There, I tried to order the most “German” thing I could, and decided that would be a mug of beer and a plate of blood sausages, accompanied with mashed potatoes and applesauce. A bit over the top, but I enjoyed it.

Stuffed to bursting, I wandered back to the train to return to Düsseldorf, where I was going to stay. But that is a story for another post.

Milan & Lago di Como

The bus from the airport dropped us off in front of a monster of a building. We were in Milan, and this was the city’s Centrale train station. Its enormous stone facade looms over the viewer, the pile of stone seemingly poised to crush you. It is, in a word, rather an aggressive structure—with ferocious eagles and lions staring malignantly from its walls. It should come as no surprise, then, that this grandiose design was willed into existence by the Duce himself, who wanted it to represent the power of Fascist Italy.

Rebe and I had come for a little break. It was May—international worker’s day—and the weather was sunny and warm. The first thing we did was to eat some pizza. Within five minutes of walking, we saw a place that looked good and went in. I have no idea if it was special by Italian standards, but the pizza was better than the best you can find in Madrid. Yes, we were in Italy.

This was my second time in Milan. My first had been in high school, on a class trip, when we had seen The Last Supper. Of course, I was too young to appreciate anything about the art (I was far more interested in the airlocks that controlled the atmosphere inside the room than the fresco itself). A decade and a half later, the city looked entirely unfamiliar to me. Not even a shadow of memory remained.

We had a little time to kill before we could check into the Airbnb, so we decided to visit the Castello Sforzesco. This is a lovely Renaissance fortification made of brick, which is free to visit. The castle is named after Francesco Sforza I, an important ruler of the city, who turned the erstwhile medieval castle into the palace we see today. One of his sons, Ludovico, was a great lover of the arts and contributed to the palace’s further beautification—notably, by calling on artists like Bramante and Leonardo da Vinci. Today, this castle is home to several museums, notably the city’s painting gallery.

But we did not have time to visit any museums. Instead, we took a stroll around the lovely Parco Sempione, a large landscaped park. And as it was quite warm, we helped ourselves to some gelato. (Since we had traveled with Ryanair, which charges for carry-on luggage, we only had small backpacks and didn’t need to find a luggage locker.)

After some time relaxing on the grass, it was time to go. Our Airbnb was not in the city of Milan. We only had three days to spend in Italy, and I decided that it would be more fun to explore the nearby Lago di Como rather than stay in the city of Milan. So we walked over to the Cadorna train station and took a commuter train north. Soon, we were all checked in, and exploring the city of Como, at the southern point of the lake.

It was a relief to be outside of a big city. A cool breeze blew off the lake and green hills rose up above us. As if hypnotized, we began to walk along the water.

Perhaps I was just sleep deprived and delirious, but I remember this walk with a strange intensity. Everything seemed colorful, new, and interesting. The ferries in the harbor, the blue hangar full of sea planes, the colorful concession stand selling gelato and panini with Italian flags waving on the top… Soon, we came across a large, classical building. This was the Tempio Voltiano, a temple dedicated to Como’s most famous son, Alessandro Volta. It contains some of the great scientist’s devices, including his voltaic piles—the first ever batteries. (Unfortunately, by the time we arrived it was closed.) Nearby is the War Memorial, a large concrete tower dedicated to those who fought and died in World War I. Built in 1933, the memorial looks remarkably more modern than that, perhaps because it was based on a sketch by the Italian futurist Antonio Sant’Elia, who himself was a casualty of the war.

We continued to wander along the lake. With every step, more of the landscape came into view. It seemed too pretty to be real. The deep blue of the water, the dramatic hills, the unobtrusive architecture of the structures, all of it combined to make a kind of living postcard. It is no wonder that this lake has been a favorite resort since Roman times. But it is a minor miracle, at least, that after so many centuries of human habituation the environment seems so pristine, and the human presence remains tasteful and discreet. Sometimes one really has to hand it to the Italians. They may seem stubborn and stuck in their ways, but they know what they’re doing.

Eventually, we came upon the Villa Olmo, one of a seemingly endless number of lovely mansions that dot the lakeside. Now, I normally have scant interest in the ostentatious residences of the very rich; but this villa and its garden—like everything else—fit so perfectly the aesthetic of the lake that I could not possibly object. It was especially charming because, just as we arrived, a troop of people in period costumes walked by. I have no idea what they were doing.

It was getting late now and we needed to find a place for dinner. We decided that we would take the funicular up to Brunate, a small village on top of the nearby hills, and try our luck there. We had to wait in a queue for about ten minutes for it to arrive—a time that was rendered almost intolerable by the presence of a bunch of Erasmus students talking loudly in front of us. (One student, after professing to know “some Spanish,” proceeded to butcher the conjugation of a basic verb in a way I did not think possible.) Finally, the machine arrived and we boarded (as far away as possible from the students). It was a lovely, if crowded, ride, and soon enough we were in the sleepy town of Brunate.

It seemed like a ghost town after Como. Very few people were in the streets, and the light was fading fast. We hadn’t eaten in hours and were starving by now. We had to find a restaurant. After a quick search online, I guided us to the Trattoria del Cacciatore, crossing my fingers that the place wouldn’t be packed. Indeed, we had the opposite problem: the restaurant was completely empty and they hadn’t even opened up the kitchen yet. I suppose Italians dine as late as the Spanish. We were told we would have to wait half an hour, but were invited into the restaurant’s large backyard to have a drink. The view was shockingly nice—the lake and the mountains stretching out before us, the sky red from the setting sun. I drank an aperol spritz before being called in to enjoy a fine meal. It had been a wonderful day in Italy.

The next day we woke up early and returned to Como. This was our big day to explore the lake. The Lago di Como is shaped like an inverted Y, with the city of Como at the southern end of the western branch. Our first destination was Bellagio, which sits right at the center, where the three branches connect. To get there, we had to take a ferry. There are several routes on the lake, some local, and others express. To save time, we elected to take one of the express ferries that go there directly—making the trip in about 40 minutes, instead of over twice that much time.

The trip had a few hiccups. For one, even though surgical masks were acceptable for traveling on trains and planes in Italy (oh, the COVID times!), for some odd reason the ferry company demanded that we use the heavy-duty N95 mask. Unprepared for this requirement, we bought some masks from some entrepreneurs selling them on the street (for a significant mark-up, of course).

Because of this scramble to cover our breathing holes, we were among the last to board the ferry, meaning we had to take a seat below deck. This was quite frustrating, since we knew the views of the lake must be gorgeous. Rebe decided to take matters into her own hands and marched up the stairs to take pictures. I attempted to follow, but was immediately told by an attendant to return to my seat. I went back downstairs feeling defeated—frustrated that Rebe was enjoying the scenery while I had a view of a wall. After about ten minutes I made a second attempt, only to be told by the same young Italian man to go back to my seat. I was flabbergasted by this, since I was standing right next to Rebe, who was entirely ignored by the attendant. Was this Italian machismo, or just chivalry? (Maybe it comes to the same thing.)

We arrived in Bellagio in good time. Like everything on this lake, but even more so, it was picture-perfect—a kind of Platonic ideal of a lakeside town. If you try to imagine a place where a world-weary Romantic poet would go to recuperate his spirits, or a disenchanted millionaire would go to discover the charms of the simple life, Bellagio is what comes to mind. It is, in short, a gorgeous town. We walked first to the end of the peninsula, which had a wonderful view of the lake with snow-capped mountains beyond. There, a woman was selling a private boat rental, which we briefly considered before we looked at the price. Then, we walked through the center of town. It was crowded with tourists and full of the expected shops selling gelato and trinkets.

The main site to see in Bellagio is the Villa Melzi d’Eril and its gardens. Melzi, the man, is principally known to history for his brief stint as the Vice President of Italy under Napoleon. But he was also an art collector who was determined to make his villa one of the greatest on the lake. He succeeded. Though we didn’t enter the villa itself, the gardens are as beautifully arranged as any in the world—full of statues, excellent viewpoints, and exotic plants, trees, and flowers. As with everything on the lake, the overall effect was of overwhelming beauty—to the extent that your eyes can hardly take it in. I wonder if the residents of the lake long for brutalist concrete structures and piles of garbage, if only for a contrast.

We went back to the dock to get on the ferry to our next destination: Varenna, which is just across the water. While Bellagio, with a population of about four thousand, feels relatively compact, Varenna is positively tiny: with 800 souls calling it home. And as tiresome as it must be to hear by now, it is another jewel. Indeed, I found myself thinking on the ferry ride that the residents of this place, from Roman times onward, had collectively turned it into a kind of communal work of art—a living landscape painting that they gradually composed.

There is really nothing to do in Varenna, which is the best thing about it. There is a kind of plaza that drops off into the water, and at any given time is covered with dazed tourists gazing at the scenery. After our own bit of gazing, we wandered inland, eventually ending up at what we would call in New York a “deli,” but which I believe the Italians would refer to us a salumeria. There, we got a couple sandwiches and then wandered into the local church, Chiesa San Giorgio. This modest bit of sightseeing done, we retreated to a nearby bar for campari sodas.

We had had an altogether lovely day on the lake. But the voyage back to Como was perhaps my favorite part. Instead of taking the express ferry, we took the local, which took nearly three hours in its meandering voyage from Varenna back to Como. If I felt deprived of lake scenery on the voyage out, I was absolutely saturated with it by the time we got back. The only thing that would have made it more enjoyable was if the ferry’s bar had been open. A nice glass of wine would have been ideal. But we were still in COVID times, and so I had to get drunk on pure aesthetic pleasure.

Our short vacation was coming to a close. The next day, we had a late flight back to Madrid. This did not leave us much time to explore Milan.

Milan is the second largest city in Italy. A capital of finance and fashion, it does not exactly fit the stereotype that many hold of Italy—neither quaint and full of art, nor chaotic and rugged. Old women aren’t shouting from their balconies and old ruins aren’t dotted the cityscape. It is, rather, a clean and rather posh place.

Our time was extremely limited, so we went to the symbol of the city: the Duomo. When we visited (and this may still be the case) you had to buy a timed ticket in order to go onto the roof. We selected a time two hours hence, and then set about to see something of Milan.

To start, the Duomo is ringed by important buildings. There is the Palazzo dell’Arengario, for example, which now houses the Museo del Novecento (museum of the 1900s). Right nextdoor is the old Royal Palace, which now serves as a cultural center. And across the piazza is the magnificent Galleria Vittoria Emanuele II. This is a beautiful shopping gallery, consisting of two arcades that intersect at a huge glass dome. The place is full of restaurants and shops that we could hardly afford even to look at, but it was a pleasure just to explore this piece of 19th century splendor. The floor mosaic in the center—representing the regions of Italy—is especially lovely. Rome is, of course, represented by a she-wolf, while Florence is a lily. Turin, meanwhile, is a much-abused bull, whose delicate parts have been worn away by visitors spinning on their heel over them. Supposedly, this brings you good fortune. Perhaps I ought to have tried it!

Then, we visited San Bernadino alle Osso, a church nearby famous for its ossuary. This is a small side-chapel that has been extensively decorated with human bones (apparently the cemetery got too full). It is free to visit and is certainly worth your time if you have any taste for the morbid.

Finally it was time for the Duomo. My first impression was of its sheer size. It is the third largest church in the world, narrowly beating the gargantuan cathedral in Seville. Stylistically, it struck me as odd. Unlike the other great Italian churches, this one is a medley of styles, owing to the ungodly long time it took to complete—from 1386 to 1965. The proliferation of spikes and spires indicates gothic (unusual in Italy, to say the least, where the Renaissance dominates), but the Milan Cathedral does not have the exuberance, the spiritual riot, of a true gothic creation. It is, rather, quite stiff and almost formalistic, the lines in its facade intersecting at right angles, ascending up in a straight line without giving a great impression of height. This sterility is due, I think, to its facade being actually neo-gothic (after all, it was completed in the 19th century).

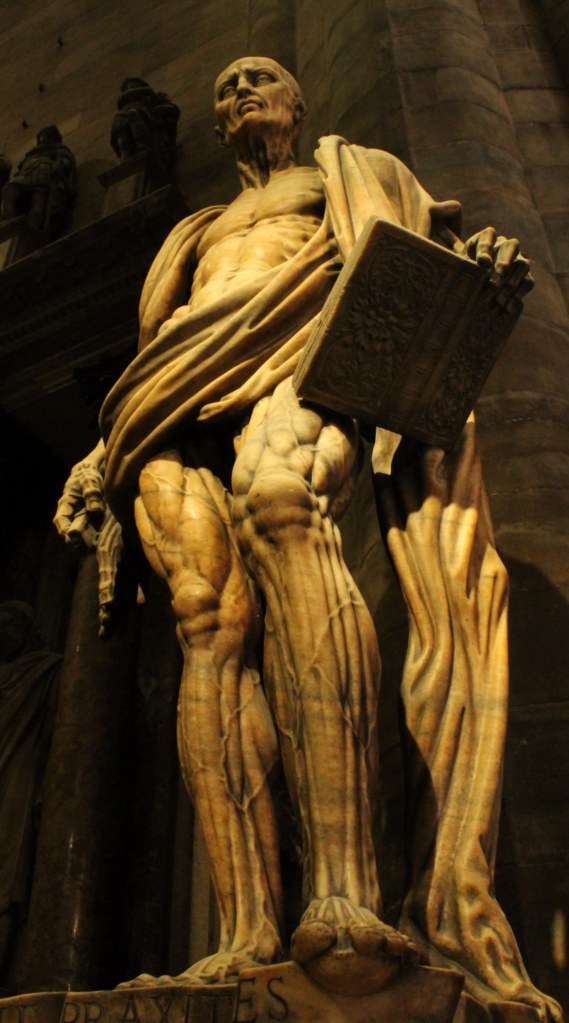

Stepping inside, I was once again astonished by its size. I also thought the interior of the church more restrained and tasteful. The same cannot be said, however, for the cathedral’s most famous statue, Marco d’Agrate’s Saint Bartholemew Flayed. Here we can see the unfortunate saint posing like a Roman senator, his skin wrapped around him like a toga, his muscles, veins, and nerves exposed. It is a kind of tour de force of anatomy, and obviously executed with a great deal of skill. But it is hard to call such a gruesome display a masterpiece.

Next, we took an elevator up to the roof. Though it was somewhat expensive (over 30 euros a person, I believe), the visit to the roof proved to be a worthwhile experience. What was nothing but a tangle of statues hanging in the air when viewed from the ground became, from up close, a kind of stone forest. While the decorative statues, judged individually, were rather generic and unremarkable, the sensation of being surrounded by so many floating figures was genuinely uplifting. The visit culminated (pardon the pun) at the top of the roof, where visitors were stretched out on the stone as if it were just another beach.

This was it for us. After a quick lunch (more pizza), we made our way to the Centrale train station and caught a bus to the airport. It had been a wonderful trip, though we had left much undone. I was particularly disappointed that we hadn’t had time to visit the Cimetière Monumentale—the city’s massive and beautiful burying ground—or the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan’s world class art museum. But after having seen so much beauty, it was impossible to have any regrets. Italy never disappoints.

Review: Long Day’s Journey into Night

Long Day’s Journey into Night by Eugene O’Neill

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

My first experience of this play was of an audio recording. It did not make an especially deep impression on me, and I was on the verge of writing a review saying as much, when another reviewer alerted me to the literary importance of the stage instructions. Chastened, I decided I ought to actually read the play before I made a fool of myself, and I’m glad I did. O’Neill, after all, never intended for this work to be produced as a play. It is, rather, like Goethe’s Faust a kind of closet drama, more effective on the page than on the stage.

The play is a masterful depiction of addiction and familial dysfunction. Indeed, I found it to be almost clinical in its psychology. O’Neill was clearly writing from personal experience. He ably captures the mixture of love and resentment that an unhealthy family bond can give rise to—perpetual annoyance, an endless buildup of grievances, non-stop bickering, all built on an unshakable foundation of love. And the characters of this play do love one another, quite dearly, even if they are stuck in a vicious cycle of blame and abuse.

Woven into this dreadful dynamic is addiction. Every member of the family is an addict, and all display the tell-tale signs. They search for excuses—good new or bad news, loneliness or companionship, special occasions or recurrent problems—to justify their habit. And then there is the deferral of responsibility, most exemplified by the mother in this play, who manages to blame everything in her life—her husband, her sons, her doctors, her upbringing—except herself for her morphine addiction. Yet of course the self-deception is never really believed. This awful truth is always there, burning underneath, a gnawing feeling that the substance will never quite deaden.

These contradictions—of great affection and resentment, of excuses and self-knowledge—are so starkly on display in this play that I think even the most brilliant actor would struggle to do it justice. The shifts of tone are too abrupt, the push and pull of conflicting feelings and truths are too violent. But, somehow, it works when read. On the page, a jostled, confused, and depressing mess becomes something orderly, transparent, and deeply tragic. A potentially pathetic group of boozers and dope fiends are transformed into symbols of aching humanity.

Considering that this play is strongly autobiographical, it is frankly amazing to me that O’Neill was able to create such a masterpiece. To confront what must have been a painful and traumatic time in his life and turn it into such a drama—a drama that pulls no punches, and yet condemns no one—is deeply impressive. As this play amply demonstrates, life too often conquers art. Routine deadens us to it, money woos us from it, addiction numbs us to it, so that we lose both our sensitivity to its beauty and the time and energy to create it. But sometimes, art conquers life. And this play is an example of that.

View all my reviews