Get the Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey Among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See by Bianca Bosker

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Much like Michael Pollan’s Omnivore’s Dilemma, I feel compelled to give this book top marks—not because I agreed with everything Bosker said, and not because I loved every moment of it—simply because I doubt a better book could be written about its subject. Bosker threw herself at the world of contemporary art with the devotion of a fanatic and the patience of a saint. This book represents, in a very real sense, a decent chunk of Bianca Bosker’s life. Years went into it.

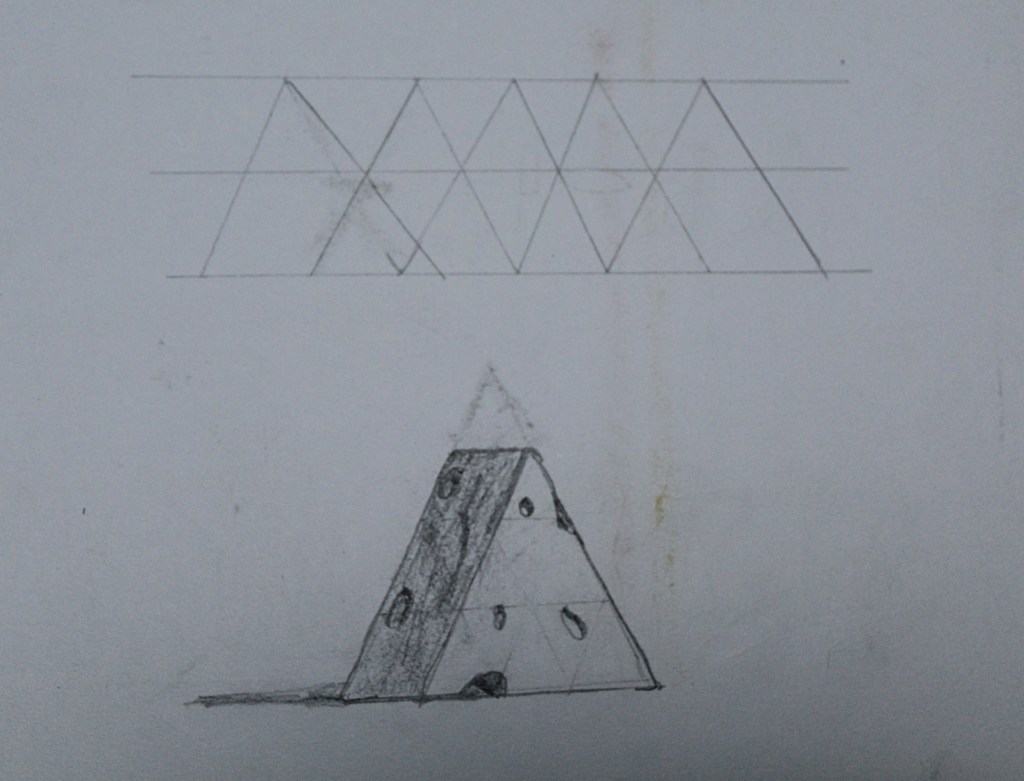

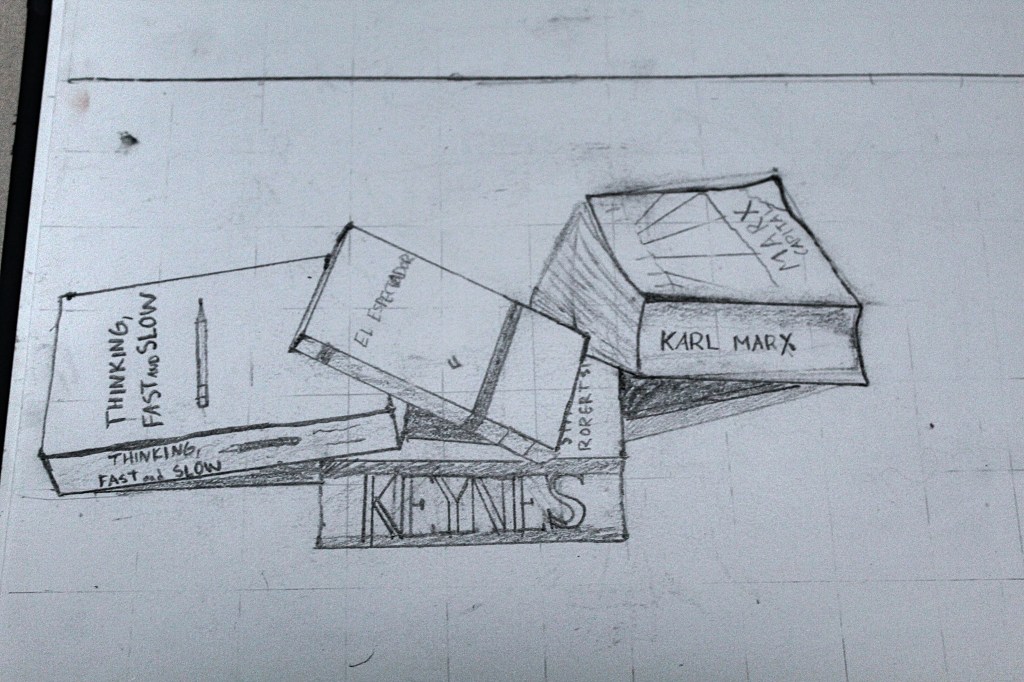

The comparison with Pollan is apt, as—like the food writer—Bosker is a kind of experiential journalist. She is not content to read art theorists and to visit a few galleries. No, she must work for a gallerist, apprentice with a painter, watch over the art in a museum, sell paintings in a show, plan an exhibition—in short, she must do everything that anyone involved in the art world does. And in so doing, she painstakingly assembles a map of this small, strange world.

The (ahem) portrait that she paints of this world is not flattering. This is especially true of the first part of the book, in which she becomes an assistant to a hip Brooklyn gallerist, Jack Barrett. I must say that I found Barrett to be the most unlikable person I had read about in quite some time—and I am including the murderous cannibals in The Road. He epitomizes everything unsavory in the art world: an obsession with reputation, with coolness, with inaccessibility, with fitting in—with everything, in short, except the art itself.

Like many gallerists, apparently, he prefers a property on an upper floor, so that it doesn’t attract street traffic. Visits from ordinary people—so-called ‘schmoes’—are to be avoided at all costs, as their appreciation is worse than worthless: it is detrimental. He even contemplates, at one point, hiring a web designer to make his website as difficult to use as possible, perhaps with white font over a white background. (Judging from his current website, this was wisely decided against.)

This emphasis on inaccessibility is certainly reflected in the language of the art world, whose style will be familiar to anybody who has been in academia. Probably many of you have had the experience of seeing something incomprehensible in an exhibition, turning to the plaque for guidance, and being confronted with a text that only adds to the confusion. As Bosker notes, this style of writing came into vogue in the 20th century, modelled after the French deconstructionists—whose already turgid prose was translated into highly unidiomatic English, and then emulated by anglophone writers. It is, in short, language meant to mystify and intimidate, not enlighten.

Most importantly, in Mr. Barrett’s world, “context” is king—which is really just a pretentious word for “reputation.” He is constantly worried about whether the people he is talking to are the “right” sort of people, in the sense that doing business with them will bolster his own reputation. When deciding whether to represent an artist, his most important question is whether they are the sort of person he would like to hang out with. He even goes so far as to nitpick Bosker’s clothes and to coach her behavior—not too many questions, no complements, no staring at the art—during their visits to galleries, since he doesn’t want her to taint his own manicured reputation.

The final irony is that Barrett, like so many in the art world, does so much of what he does in the name of progressive values, while personally betraying them. Several times, for example, he berates older painters and art critics (like Kenneth Clarke) for their focus on the female body, but he has no problem openly criticizing Bosker’s outfits, and even her exercise habits. He is critical of the white male establishment while being, quite obviously, a part of it—someone who is certainly from a rich family, but who hides his background so as to conceal his own privilege. And he is far from an aberration: as Bosker points out, the majority of galleries are owned by white males.

I am probably spending too much time on Barrett, who really only occupies the first quarter of the book. But I found his entire attitude towards art to be so poisonous that I could hardly even believe that such a person could really exist, much less be (as Bosker insists) one of the ‘nicer’ gallery-owners in New York. Yet perhaps the most damning fact is that, as Bosker points out, Barrett rarely if ever comments on the formal qualities of a work. In the rare moments that he deigns to explain why he likes a particular piece, he resorts to interpretations that rely on his knowledge of the artist—of “context,” in other words. If the book consisted solely of Bosker’s experience with Barrett, one would have to conclude that the art world was entirely and utterly vapid.

But Bosker has an incredible capacity for hope; and even after her tense working relationship with Barrett breaks down completely (he implies that he purposely told her the wrong way to paint a wall, so that he could criticize her for doing it wrong), she persists and actually succeeds in meeting some pretty nice people. The next gallerists she works for tell her, contra Barrett, to “stay in the work”—to appreciate the art you see in front of you, and not fall back on its reputation. And rather than insist on a frigid dress code and an affectless demeanor, they are bouncing off the walls with enthusiasm for the art they sell.

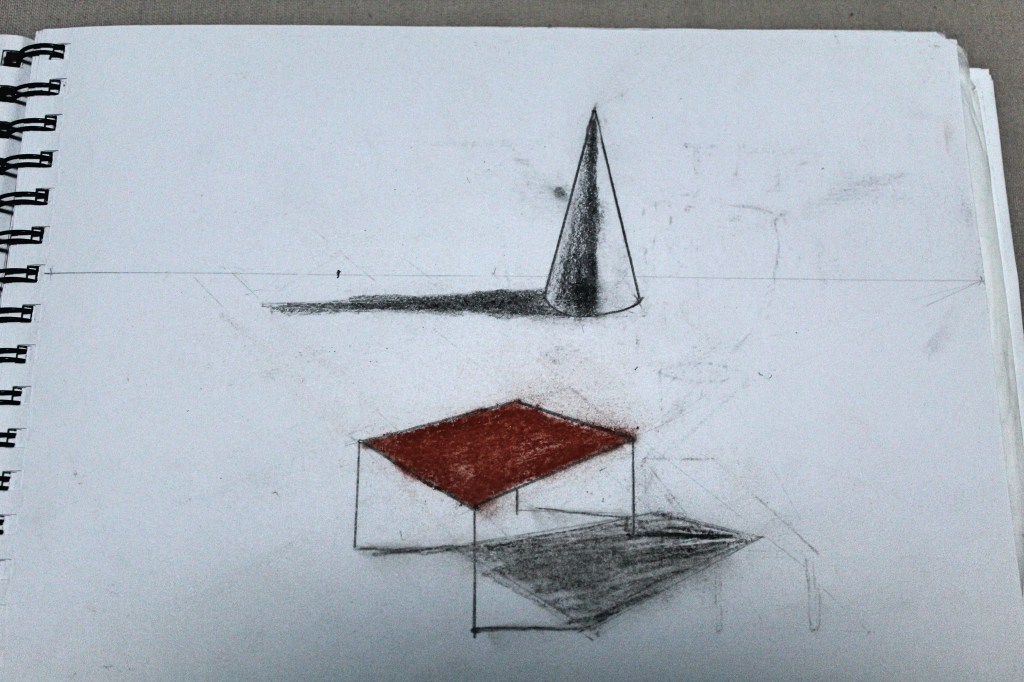

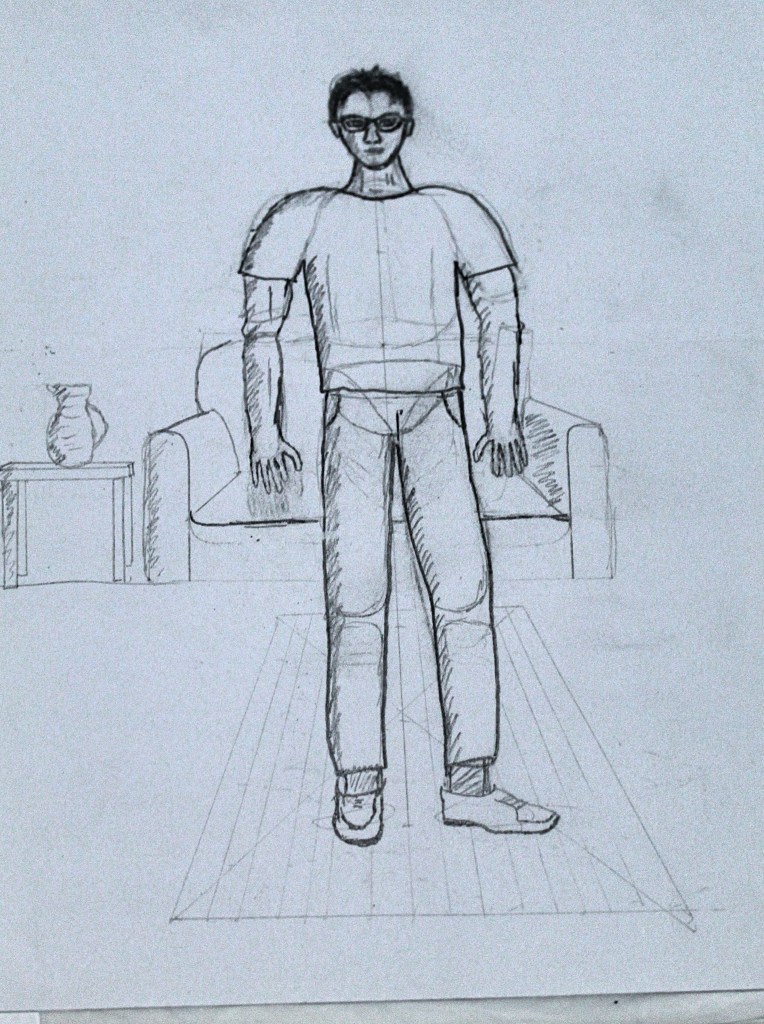

Yet the hero of this book is, undoubtedly, Julie Curtiss. With all of the focus on gallerists, curators, and collectors in the beginning half of the book, it is easy to forget the actual people who make the art. And Curtiss, whatever you think of her work, is every inch an artist—manic about her craft, able to talk your ears off about color, a perfectionist in every detail, and motivated by a kind of ineffable aesthetic vision. In stark contrast to the Barrett camp of art, Curtiss seems motivated purely by the formal qualities of her work—a vision in her head that she is trying to make manifest. What it means—whether it means anything—is of far less significance.

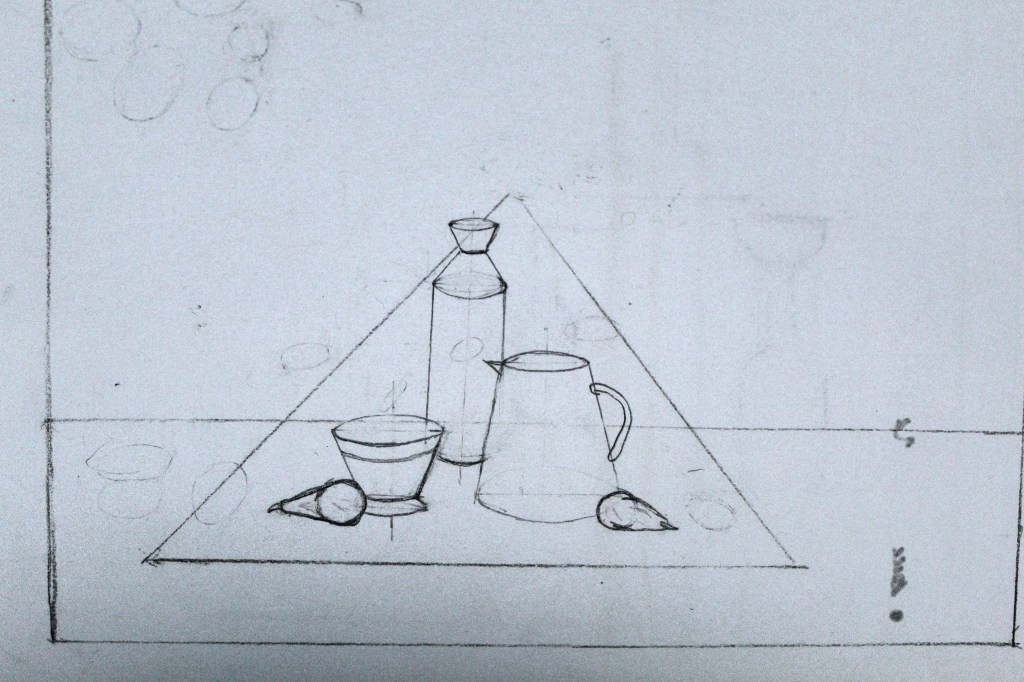

Bosker ends the book by taking her own stab at the question: What is the value of art? She decides that art works by reuniting us with the basic data of our senses. As she notes, our brains are constantly taking the information from our eyes and fitting it to preconceived patterns, which aid us in quickly making sense of what we experience. The advantage of this is greatly increased processing time (we know a lion immediately when we see one), but the disadvantage is that we can become disconnected from the real stuff of experience. Art breaks this pattern by presenting images to our brains that we can’t immediately make sense of.

Now, I think there is a great deal to be said for this view. For one thing, it avoids the over-reliance on “context” that plagues so much modern art—a sculpture of a coffee mug that comes with an essay about modern-day consumerism. However, as an attempt to come to grips with art it strikes me as both too broad and too narrow—too broad, in that many things besides art can reconnect us with our senses (travel, drugs, exercise…), and too narrow, in that art can do more than just attune us to the beauty of color and form. Yet it is difficult to criticize Bosker on this point, given that Plato and Kant also tried and failed to come up with an all-encompassing philosophy of art.

In any case, before writing this review, I made sure to try to put Bosker’s advice into practice. Last Saturday, I went to the Reina Sofia museum and forced myself to stare at art that, otherwise, I would probably have scornfully walked right by. As she advised, I tried to notice at least five things about each work I focused on, and even set a timer on my watch for five minutes, not allowing myself to move on until the time ran out. Perhaps this sounds more like a form of self-hypnosis or meditation than genuine art appreciation, but I did find myself enjoying some rather far-out contemporary works that were not to my usual taste.

And it is a great testament to Bosker’s book that, in spite of the (ahem, ahem) ugly picture she paints of the art world—so full of empty pretensions and hypocrisy, a “progressive” world of starving artists and rich collectors—that despite all this, she still deepened my enjoyment of contemporary art. It is a masterpiece.

View all my reviews

Cover photo by Wallygva at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15372441