2020 on Goodreads by Various

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Well, this has been quite a year.

I began by reading the latest release of one of my favorite authors, Bill Bryson, about the human body. I devoured this book—a Christmas present—with the kind of rapacious glee that comes over me whenever I discover an untapped well of unfamiliar facts. It had never even occurred to me that the human body could be so strange and so mysterious, or that there was still so much we do not know about our organic vessels. One particular moment sticks in my memory: The section on infectious diseases ends with a warning that another 1918-type pandemic is very possible, and that we are little better prepared to deal with it. I remember this because I actually scoffed at it, thinking the notion alarmist.

Life went on as planned, at least for a while. My big idea was to continue reading about economics, mathematics, and the history of science. I listened to several Great Courses, struggled through the works of Archimedes, and beat my head against a biography of John Maynard Keynes. Unfortunately, I remain much unimproved; but at least I finally read Daniel Kahneman’s fascinating work on the psychology of decision-making (another Christmas present), which has quite serious ramifications for economics.

Then the coronavirus hit, derailing my reading as well as the rest of my life. While many used reading as a means of escapism, I felt extremely frustrated by my lack of understanding of what was happening, and so I embarked on a series of books about diseases. This began with Micheal Osterholm’s book about infectious illness, Deadliest Enemy, which is a kind of all-purpose primer about the threats posed by different sorts of germs. I recommend it. Another all-purpose analysis is William McNeill’s speculative book on the impact of infectious diseases on human history. This was followed by John Barry’s history of the 1918 pandemic (also recommended), Richard Preston’s account of Ebola, Andrew Spielman’s summary of mosquito-borne illness, and Daniel Defoe’s fictional narrative of the bubonic plague. The best book of the lot was And the Band Played On, Randy Shilts’s devastating report of the AIDS epidemic in America, which unfortunately has many parallels in the handling of the pandemic by the current administration.

In June, the pandemic restrictions were mostly lifted in Spain. Meanwhile, Black Lives Matter exploded across the world, and the American elections came into focus. This prompted another reading adventure. I had the idea of reading at least one book about each major problem facing my beloved and beleaguered country. This began with David Wallace-Wells dire warning about climate change (potentially much worse than a pandemic!), Uwe Reinhardt’s mordant criticism of the abysmal American health system, and Sara Goldrick-Bar’s study on the difficulties of paying for higher education. Alex Vitale made the case for defunding our militarized police force, Angela Davis urged for decarceration, and Michelle Alexander—in perhaps the most eye-opening book of my year—compellingly argued that mass-incarceration was just another chapter in American racism.

Economics looms large in any diagnosis of societal ills. Andrew Yang, William Julius Wilson, and the co-authors Nicholas Kristoff and Sherlyn WuDunn all came to similar conclusions: that good jobs are disappearing from many parts of the country, with devastating social consequences. David Harvey, Thomas Piketty, and the co-authors Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo analyzed this same worrisome trend on a macro-scale, and came to essentially the same conclusion: that the rich are getting richer and the poor poorer, in part thanks to neo-liberal economic ideas (“trickle-down economics”) which have failed quite abysmally in delivering on promised growth. But as an analysis of economic woes, no book was more revelatory than Matthew Desmond’s book on eviction—easily one of the best, and most depressing, books of my year. Before leaving politics, I should also mention David Hemenway’s analysis of gun violence, Herman and Chomsky’s critique of the mainstream media, and two very upsetting works of journalism about the presidency of you-know-who.

Since I devoted so much energy to all this nonfiction, my fiction reading was necessarily limited, though I did get around to many books which had long been on my list: Henry James’s The Ambassadors, D.H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks, Lord Byron’s Don Juan, Gabriel García Márquez’s Cien años de soledad, John Williams’s Stoner, and Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. To a certain extent, I liked all of these books, some of them very much; but I cannot say that any of them were the gut-wrenching literary experiences I was hoping for. My year in philosophy was even less impressive, consisting only of Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation, which mostly left me cold.

But I did learn some new things. I revisited college chemistry with lectures by Ron B. David, Jr., and I also make some clumsy attempts at learning to draw. My biggest accomplishment was probably my German. Lockdown provided me with a lot of time to regain all the proficiency I had lost since switching my focus to Spanish, and I think I am now better than ever before. And of course there were many books that did not fit into any of the above categories, some of them quite excellent, like McCullough’s history of the Wright brothers or Murakami’s essays on running.

On the whole, then, I think I must rate this year very highly, if only because I learned so many things—about history, disease, politics, economics, science—that I had not even considered learning before. Somehow, my main coping mechanism (read a book about whatever it is that is giving me anxiety) served me well during this whole, 365-day ordeal. I do hope, however, that I will not have to use it so much in the year ahead.

Thanks to you all for being a part of this great community. This year would have been worse without you.

View all my reviews

Month: December 2020

The Statue of Liberty & Ellis Island

It was a thoroughly muggy day in mid-August when I boarded a boat in Battery Park.

My destination was the most famous statue in the United States, if not the world. And I was willing to pay to get up close. Now, if you merely wish to take a good picture of the statue against the New York City skyline, then no financial transaction is necessary. The Staten Island Ferry—a gratuitous vaporetto—passes quite near Liberty Island, allowing its parsimonious passengers an excellent vantage point from which to gawk and snap photos. But I was in no mood for drive-by glances; I wanted to see the statue from dry land, which requires a certain amount of money.

In the time before COVID-19, the ferry company had no qualms with herding us through a large security tent and then packing us into the boat like salted fish. I opted to stand on the deck. Despite the summer heat and the humidity, the sea wind whipped up soon after we set off, giving me goosebumps. But this was compensated by anticipation. Even a short ferry ride partakes, however modestly, in the romance of travel by sea. And as a good friend of mine once said (well, he said it repeatedly): “The best way to see a city is by boat.” This is certainly true regarding New York City, at least. Seen from the harbor, the Manhattan skyline is at its most vertiginously dramatic. The Statue of Liberty is not bad, either.

In about twenty minutes the boat docked at Liberty Island. Now, this was not always the name of this little piece of earth. Before Europeans came to dominate the land, the Canarsie people called it Minnisais. Since then, however, the island has been dubbed Love Island, Great Oyster Island, and Bedloe’s Island, among other appellations. It had many uses before being made home to an enormous copper goddess. Food was grown, men were hanged, garbage was dumped, and Tories waited here to be extracted to England. The island was even used as a kind of lazaretto for those suspected of harboring smallpox. Its last function before being turned into a monument was as a fortified battery; and the star-shaped remains of Fort Summer still sit below Liberty’s green heel.

I pushed my way down the boarding ramp and headed straight for the statue. This was not my first visit. Many years ago, when I was still in middle school, I visited the island with my Californian cousins, who wanted to see some of the main sights of New York. At the time I was inclined to see any sort of cultural excursion as a monumentally boring waste of time. Video games were infinitely more entertaining, and I resented my family for dragging me away from my computer. Nothing I saw made much of an impression on me: not the Empire State Building, not Wall Street, not Battery Park. It was wholly unexpected, then, when I found myself entranced by the Statue of Liberty. I could not take my eyes off it. I even felt inspired. Somehow the statue had broken through the many layers of youthful apathy and juvenile ignorance to touch a hitherto unknown part of myself.

This second visit was not quite as stupendous, if only because by this time I had grown accustomed to visiting monuments and the feelings that they evoke. This is not to say that I was uninspired. The towering lady is not as dynamic in composition or as beautiful in form as, say, Michelangelo’s David; and the sickly green color (caused from the oxidation of the copper) is not the most aesthetically pleasing shade imaginable. (Like the oxidized patina itself, however, it grows on you.) But statues of this size have different engineering constraints, not to mention serving a different purpose. As a synecdoche of the nation, as a grandiose welcome to those arriving by sea (many of them immigrants), and as an artwork that represents the Enlightenment values that (nominally, at least) set this nation apart, Liberty Enlightening the World could hardly be more successful. Granted, Bartholdi probably only intended some of this in his design; yet the mark of any great work of art is that it goes beyond even the vision of its creator.

I had opted for the cheapest ticket, which only allowed me to gaze at the statue from without. Paying more would have given me access to the pedestal, and still more would have allowed me to ascend to the seven-pronged crown. (Visits to the torch have been prohibited since 1916, for a somewhat obscure reason.) But even the most basic ticket seemed pricey to me. So after I had taken my fill of the statue, and walked around her a few times, I wandered over to the other end of the island to see the museum. The visit begins with a strange cinematic experience, wherein visitors are led into a big, empty room, shown an informational video about the statue’s history, and then led into another room where the video continues, and then yet another. I suppose they screen the film this way so that more visitors can be shown it at once, though I did wish there were seats available.

The museum in general was surprisingly good. There are models of the statue and its innards, a great deal of information about its construction and inspiration, and even real models and former parts. But rather than try to narrate the museum, I will use it as an opportunity to tell something of the statue’s history:

Given that Lady Liberty is one of the most quintessentially images of America, it is somewhat ironic, then, that the statue was designed and built entirely by the French, and given to us in an act of international generosity. I can think of no other major monument with such an origin.

The idea for a celebratory dedication to the United States evidently originated with Édouard René de Laboulaye, a prominent French abolitionist, who wished to celebrate the Union victory in the Civil War, and the end of American slavery. This proposal was taken up by his friend, the artist Frédéric Bartholdi, who liked the idea, if only because it would have provided an indirect rebuke to the repressive regime of Napoleon III. But such projects are seldom conceived and completed on schedule; and by the time the statue was finally built, in 1885, Napoleon III had been deposed.

It was difficult enough for the cities of Brooklyn and New York (when they were formally separate) to work together to plan, fund, and execute the Brooklyn Bridge across the East River. Imagine, then, the nightmare of coordinating an international project across the Atlantic. To build the statue, Bartholdi had to personally come to the United States, scout out a good location, meet with the president (Ulysses S. Grant at the time), and then cross the young nation trying to drum up support. Batholdi also had to come up with a design. That the theme should be liberty was obvious; but freedom can take many forms. It can be a bare-chested woman leading troops into battle, à la Delecroix; yet that seemed too violent or revolutionary. Instead, Bartholdi opted for a neoclassical design, staid and solemn, robed in a Roman stella (togas are for men), crowned with a diadem, and holding a torch rather than a sword.

In 1875 Bartholdi and Laboulaye set to work raising money for the statue. It was to be a long slog, combining a difficult PR campaign with a vast logistical challenge. Building material was needed, talent had to be recruited, and the public interest maintained at a high enough level to keep funds flowing. As an engineering task, the statue was daunting enough. Standing 46 meters tall, the statue had to support 91 tonnes of metal without crumpling or toppling over. The thin copper skin simply would not bear that much weight, and so Gustave Eiffel was contracted to design an internal steel skeleton. This internal work is a magnificent achievement in itself, since it could be easily assembled and disassembled, and also because Eiffel designed it in such a way as to allow the metal to expand and contract in the changing weather without cracking the skin. Were the copper exterior removed, then, New York would have her own Eiffel Tower.

While the French were busy with the statue, the Americans had to make the pedestal. This proved to be quite a challenge, for the simple reason that nobody wanted to cough up the money. Grover Cleveland—who was then the governor of New York—vetoed funding for the statue, which left the project lingering in unfunded purgatory. (Cleveland, as president, later presided over the dedication of the statue, which seems terribly unfair.) The task to fund the project fell, instead, to private industry and the good people of New York. Specifically, Joseph Pullitzer led a funding drive in his newspaper, The New World, promising to publish the name of every single contributor. Thus the pedestal was built with spare nickels, dimes, and pennies, mailed in from children, widows, and alcoholics. Even so, it took longer than expected to raise the required sum, and the pedestal was still incomplete by the time the statue arrived by steamboat.

The assembly and disassembly of the statue, transportation across the seas, and then reassembly in its new home, was yet another massive engineering challenge for the designers. Eiffel’s steel beams arrived with Bartholdi’s hand-beaten copper, and teams of workers had to put it all together, like an enormous erector set. The statue’s completion was celebrated by the city’s first ticker-tape parade, which culminated in a yacht trip to the island for a private dedication ceremony, attended only by politicians, dignitaries, and other officials. Ironically, in a fête for an enormous female, few women were permitted to attend. The values of the Enlightenment have their limits, after all.

My sojourn on the land of liberty had come to close; but I still had more to see. Tickets to visit the Statue of Liberty come included with a trip to Ellis Island, just a few minutes away. Like Liberty Island, this island used to be called Oyster Island, for the very logical reason that it was a shallow tidal flat where oysters liked to live. As such, it was used as an important food source by the Lenape people, but they called it “Kioshk” for the many seagulls which liked to rest there. Much later, when an island was needed to process the increasing tides of immigrants, the government started dumping sand, rocks, and soil (taken from the subway tunnels) in order to create something fit for permanent habitation. (This had very unfortunate results for the oysters, which scientists are now trying to revive in the Billion Oyster Project.) Ellis Island was not even originally a single island, but three separate ones which were gradually merged. The current landmass is shaped like a fat “C,” and ships dock in the space between the northern and southern halves.

Ellis Island has come to serve as a symbol of American immigration, but of course this particular institution represents only one chapter of the story. Ellis Island was never the only port of entry into the United States for immigrants, and it was active for only about thirty years, from 1892 to 1924. Most of these immigrants coming through Ellis Island were, naturally, from the other side of the Atlantic, specifically Europe. This includes Germans, Irish, Scandinavians, a great many Italians, Eastern European Jews escaping pogroms—and many more, to the tune of 12 million souls. It has been calculated that 40% of the United States population can trace at least one ancestor to Ellis Island (though I do not know if that includes me).

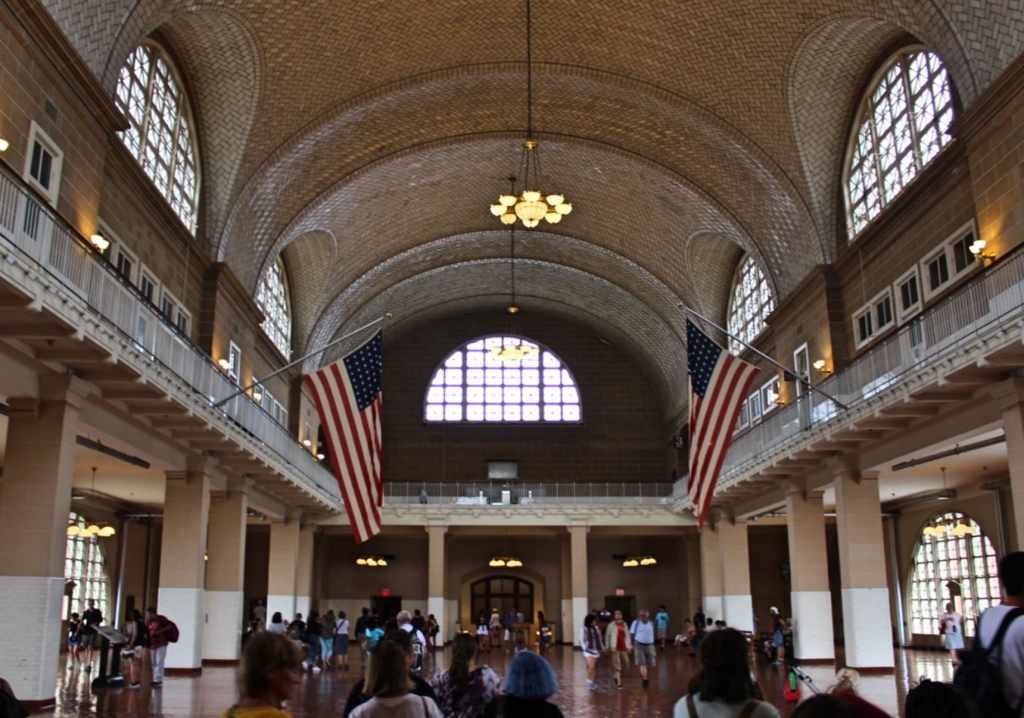

The basic visit is to the island’s Main Building. This is a large and surprisingly beautiful structure, built in a French Renaissance style. Your visit is meant to replicate the journey of an arriving immigrant to the island. You begin in the baggage room, complete with real period suitcases and trunks, where you pick up your audioguide. Then you advance to the registry hall, a cavernous open room topped with Guastavino tiles, which shimmer and sparkle in the indirect light. But I doubt that an arriving immigrant would have been in the mood to admire architecture, since this room was the scene of fateful decisions.

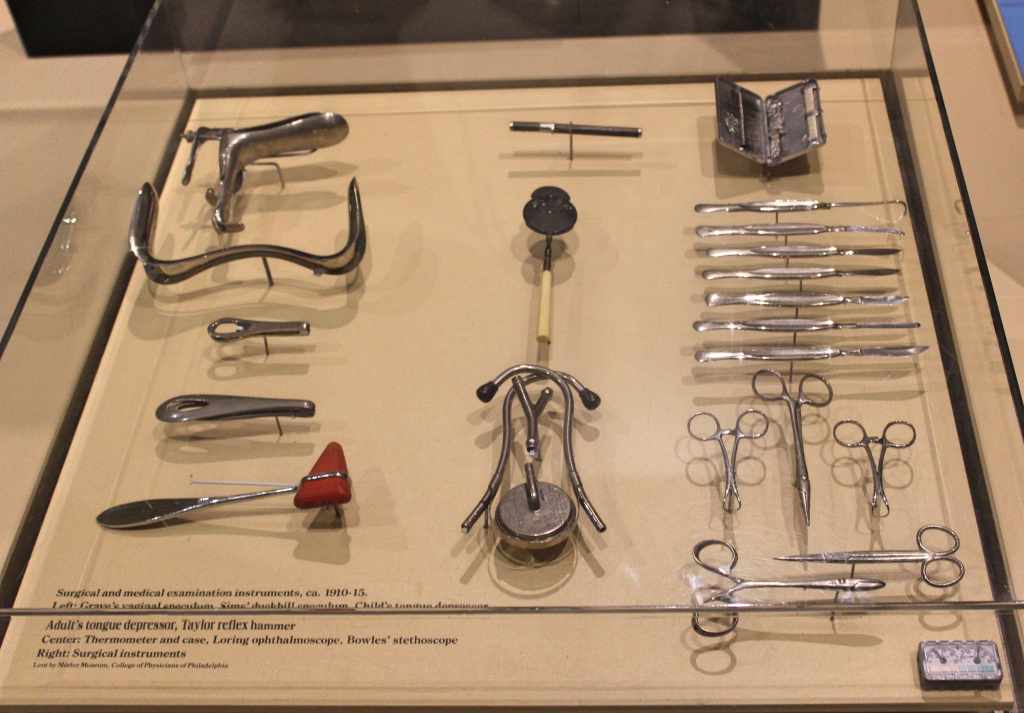

While the hall is now open and luminous, during the heyday of Ellis Island it would have been full with queues upon queues of incoming immigrants, awaiting their turns on long benches to talk with a customs official. While they entered and waited, doctors would inspect and examine the hopeful immigrants for any signs of ill health. Those presenting a worrisome sign would be marked with chalk and more thoroughly examined. If the problem was grave, or the disease highly contagious (like trachoma, an eye affliction), the poor soul might be sent all the way back—a fate of a small minority (about 2%), but a very crushing fate indeed after spending one’s savings and crossing an ocean in the hopes of a new life. If the problem was less severe, then the migrant may be in for a stay at the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital (more on that later).

In any case, even for the well in body in mind, the experience must have been extremely stressful. For the most part, the rich are not the ones who emigrate; it is the poor, with little money to spend. Consequently, then, the voyage aboard the steamers crossing the Atlantic was abysmally uncomfortable—cramped, cold, dark, seasick and poorly fed. Then the storm-tossed travelers were thrown into a hall echoing with unintelligible languages to be handled by unfeeling officials.

Thankfully, for the majority of those arriving on Ellis Island, the affair was quite short, lasting only a matter of hours before they were allowed through. Laws regarding immigration were, after all, far more lenient back in the day, especially in the decades leading up to World War I. Stefan Zweig, for example, remembers traipsing around Europe without even possessing a passport. But that war initiated a period of nationalism and xenophobia on both sides of the Atlantic. A literacy test was mandated in 1917 (in the immigrant’s native language), and by the 1920s quotas were imposed, thus ending the period of mass immigration.

From the registry hall, you move from room to room, each one used to process the immigrant in a different way—further health inspections, mental aptitude tests, literacy tests, legal processes, money exchanges, bus tickets, and so on. A courtroom was busy hearing cases of immigrants suspected of being professional paupers or contract laborers (oh, the horror!); luckily, immigrant aid societies paid for lawyers to help appeal cases, and 80% of the immigrants on trial were accepted. Particularly fascinating to me were the examples of IQ tests, meant to weed out those considered to be mentally infirm or deficient. This was a challenge, since the tests had to be applicable to anyone, regardless of their national background. Even a simple task, like drawing a diamond, was not a fair measure, since a large portion of immigrants had never even held a pencil. The psychologists thus settled on visual tests, like identifying faces or distinguishing between images. Still, the whole attempt seems rather silly in retrospect.

To repeat, for the majority of immigrants, Ellis Island was only a brief stopover. But a sickly minority required a longer stay—days, weeks, or even months—in the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital. For some, this meant a stay to “stabilize” their condition before being sent back, but for others successful treatment was an entry ticket to another life.

The hospital is on the other half of the island, and off limits to the casual visitor. To go, one must sign up for a guided hard-hat tour, as the buildings are nowadays in a quite dilapidated condition, empty and overgrown. But at one time this was one of the biggest public health hospitals in the world, complete with separate words for infectious diseases. Nowadays, in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, we can appreciate the role of border control in controlling contagious illness. This idea was old even by the time Ellis Island was built (there are islands for isolation in the Venetian lagoon, for example), though of course it was never a fool-proof way of controlling epidemics—such as the waves of cholera that arrived from the Old World. Still, Ellis Island was an important line of epidemiological defense for the United States.

Taken together, the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island are the country’s greatest monuments to the immigrant—symbols of the country’s open-armed embrace of anyone willing to come. At a time when anti-immigrant sentiment is once again raising its ugly head, these monuments are more important than ever, for they remind us that the majority of us are descended from immigrants, most of them poor, most of them uneducated, and all of them looking for a better life. How were those Hungarians or Italians, unable to write or even to hold a pencil, any different from the people now at our southern border, who fill us with so much fear?

Economists may show us, again and again, that immigrants do not steal jobs; and historians may demonstrate that xenophobia is used, again and again, as a scapegoat for other social ills. But no argument is as profoundly moving as that lady of oxidized copper, herself an immigrant, holding out her torch towards the vast and windy seas, inscribed with the words of Emma Lazarus:

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Washington D.C. and Arlington National Cemetery

Some capitals are far older than the countries to which they belong. This includes Lisbon, Paris, London, and Rome—all ancient settlements which survived the rise and fall of many states. We have very little idea how these cities were founded, who exactly founded them, or when exactly they first came into being. None of this is true in regards to America’s capital city. Washington D.C. is younger than its country (by one year), and we know nearly everything about its creation.

When George Washington was inaugurated as the first president of the United States, in 1789, it was not, of course, in the city that now bears his name, but in New York City. Many in his cabinet—including, most notably, Alexander Hamilton—would have been quite happy to have left the capital right there, in the nation’s largest and most cosmopolitan city. But a powerful contingent from the south feared that this would give the northern moneyed interest too much sway over the nascent country. Therefore, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison pushed to have the nation’s capital established in the south.

Although Hamilton did not get along with the two Virginians, they somehow managed to come to an agreement, in what we now dub the Compromise of 1790. (The details of the negotiation are impossible to pin down, since it took place at a private dinner.) In return for allowing the federal government to assume the states’ war debts—thus helping to establish the new country’s credit—Hamilton agreed to have the capital established along the banks of the Potomac. Thus, even before the ground was surveyed, Washington D.C. was marked by backroom political haggling.

Though most everyone is aware that the city is named for our first president, there are fewer, perhaps, who know that “Columbia” was a kind of highfalutin name for America. The city was built on land donated from Maryland and Virginia—though in the tensions leading up to the Civil War, Virginia cordially decided to take its land back. The city owes much of its shape to a foreigner, the Frenchman Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a Revolutionary War veteran who came up with the basic grid layout. His original plan for a presidential mansion five times the size of the White House was, however, mercifully not put into action.

Washington D.C. has grown into a medium-sized city, with about 700,000 residents. But when its entire metropolitan area is included, the population rises to 6 million, making Washington D.C. the sixth-biggest urban center in the country. Yet the city still retains the artificial character of its origin. A friend of mine once described D.C. as having “all the hospitality of the north, and all the efficiency of the south.” Though perhaps a bit too hard on the capital, this description does capture the strange lack of personality that struck me as I first stepped foot D.C. It is a place of many monuments and little life.

But I do like a good monument.

The taxi left us—my dad and my brother, plus me—at the National Mall. It was a muggy day in early September, and the blue sky was heavy with clouds. The only structure breaking the sky was the familiar form of the Washington Monument.

This was the first time I had seen the famous tower since I was in middle school, and I was surprised by its height. Indeed, the Washington Monument is fairly massive: standing over 500 ft. (150 m), it is simultaneously the tallest obelisk, the tallest structure made of stone, and, for five glorious years, it was the tallest structure in the entire world. (The Eiffel Tower put an end to its brief reign in 1889.) It is also curiously discolored, as a result of using marble from two different sources during its construction—which in turn was a result of a long hiatus in construction, caused by a lack of funds and the American Civil War. As the ancient Egyptians could have told us, building obelisks is not as simple as it seems.

Our first stop was the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which is one of the many Smithsonian museums along the National Mall. Housed in a decidedly futuristic building—like a step pyramid that had been turned over—the main collection is displayed underground. This museum was only opened in 2016, a shocking fact, considering that the Holocaust museum opened almost two decades earlier. It is always easier to deal with the crimes of others, I suppose. Considering how important it is for the country to come to terms with African American history, it pains me to criticize this museum. However, I must admit that I was disappointed by the visit, partly because there was a great deal of text to read in the poorly lit, underground rooms, and also because I found the history presented to be almost the identical story that was taught to me in high school, and thus already familiar. Such a museum should not feel like a textbook but a reckoning.

We emerged, blinking, back into the hazy D.C. summer day. To our right was the grand obelisk, and all around us were grass and trees. This was the famous National Mall, a green area stretching from the Lincoln Memorial, to the east, to the Capitol building, to the west. (While it does seem appropriate that the center of American power is a mall, the name derives from an older version of the word, meaning a sheltered promenade.) The entire area from the Washington Monument to the Capitol is dotted with enormous museums, all administered by the Smithsonian Institute.

Strangely enough, the name of this august body comes from a man named James Smithson, an Englishman and a bastard in the technical sense, who spent much of his life running around Europe performing scientific research. A bachelor, he left his estate to his nephew, with the stipulation that, were his nephew to also die without an heir, the money be used to set up an “establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men” in Washington D.C. The nephew did duly die childless, and so the Smithsonian was born. It is rather strange that Smithson chose Washington for this bequest, since he never visited the United States. And so our most prestigious center of knowledge bears the name of an aloof English bastard.

The Smithsonian, as it exists today, is beyond the bounds of even the most eccentric English scientist. All told, the Smithsonian administers 50 institutions—including museums, research centers, libraries, and even a zoo—and its collection is numbered in the tens of millions of items. Much of the money used to fund this vast edifice of knowledge comes from the humble tax-payer, who is rewarded by being allowed free entry into any and all of the Smithsonian museums. The headquarters is quite conspicuous among the enormous buildings of the National Mall. Nicknamed “The Castle,” it is built in a kind of flamboyant medieval revival style out of red sandstone. This eye-catching design, by the way, was the work of James Renwick, Jr., who is also responsible for the even more resplendent St. Patrick’s Cathedral in NYC.

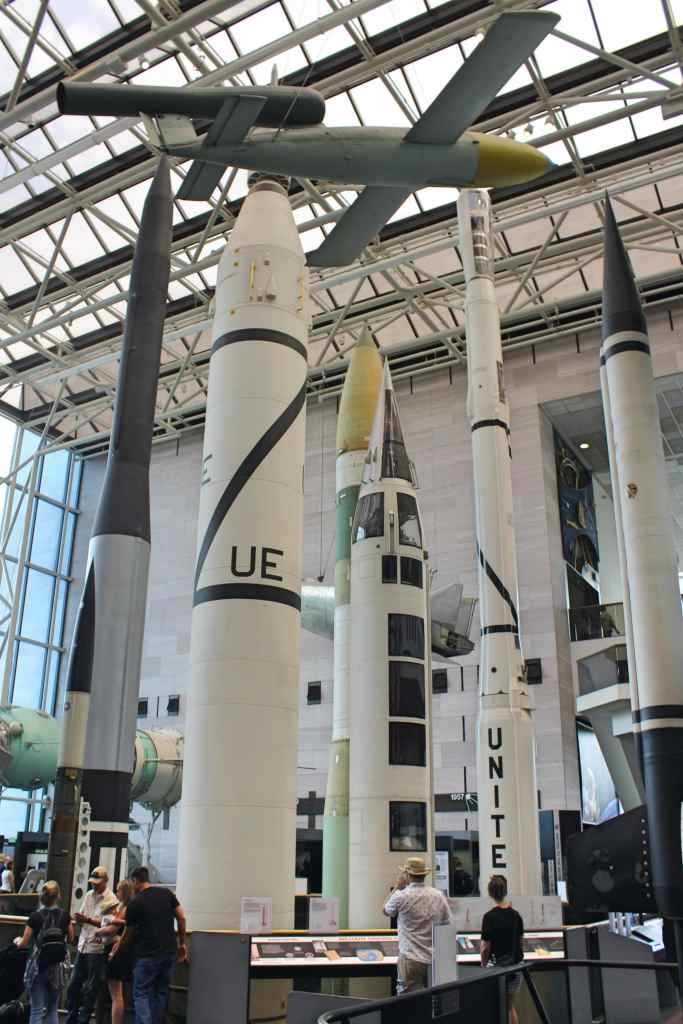

We had many museums to choose from. Besides the previously mentioned, there was the Museum of American History, the National Gallery of Art, the Museum of Natural History, the Museum of the American Indian, the Hirshorn, the Renwick Gallery, the Museum of African Art… All wonderful museums, I am sure, and all within close walking distance. But, for my part, if you are in Washington D.C. and hoping to rekindle your patriotism and American pride, the best place to go is the Air and Space Museum.

If you retain even one iota of the childhood wonder of human flight, then the Air and Space Museum will be a delight. It is exactly what you would expect: room upon room full of fighter jets, propeller planes, gliders, rockets, missiles, satellites, space shuttles, and landing craft. So many of these vehicles are connected with American firsts—the first airplane, the first transatlantic flight, the first man on the moon—that a visiting citizen cannot help but feel a mixture of pride and also nostalgia, since these great achievements now seem so very distant. Indeed, the Cold War still hangs over this museum like a stubborn ghost, as it was this conflict which spurred us to the furthest reaches of the atmosphere and beyond.

My favorite part of the museum was the exhibit on the Wright Brothers, which has the original Wright Flyer on display. The exhibit was conspicuously well-written; indeed, its tone was so highly reminiscent of the historian David McCullough, that it made me wonder if he had written the plaques himself. After this exhibit, I was so impressed by the Wrights that I decided to pick up McCullough’s book on the inventors, which I highly recommend. The brothers were far more than idle tinkerers, as I had assumed; they were brilliant mechanics and dogged problem-solvers, who accomplished something many people thought impossible. Seldom has a single invention so entirely changed modern life as the airplane; and its inventors were bike mechanics.

After taking in our fill of space suits, cockpits, engines, wings, slats, spoilers, and flaps, we went back out into the mall for a bite to eat. There were plenty of food trucks around, so this was quite easily accomplished. A few dollars bills exchanged, a few chunks of greasy meat swallowed, and we were ready for the next museum: the National Gallery of Art.

This is the Smithsonian’s enormous homage to Western culture. The central building has a façade and dome made in imitation of the Pantheon in Rome; and its spacious wings are full to the brim with paintings from Spain, France, Italy, England, and the Netherlands (not to mention the United States). Stretching from the middle-ages to the twentieth century, the collection is remarkably high-quality. There are self-portraits by Rembrandt and Van Gogh, studies of light by Monet, atmospheric symphonies by Turner, dancers by Degas, landscapes by Cezanne, and portraits of all the founding fathers. El Greco’s magnificent Laocoön is to be found here, as well as a breath-taking full-length portrait of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David. Most spectacularly of all, the National Gallery has the only work of Leonardo da Vinci to be found in the country: Ginevra de’ Benci. In sum, I think the American National Gallery is fully the rival of its counterpart in London, which is high praise indeed.

While we were about halfway through the visit, my brother slipped off to meet a friend of his in the area. The two of them visited the National Portrait Gallery, where, among other works, there hangs the iconic presidential portrait of Barack Obama, by Kehinde Wiley. I wish I had gone to see it, too.

Now, at this point my visit to D.C. became somewhat jumbled—what with going out to eat, rendezvous with family, returning to the hotel, meeting local friends, and so forth—and so I will forego any pretext of narrating my own visit in order to round out this portrait of the National Mall.

At the eastern end of the Mall stands the most impressive structure in the entire city: the Capitol Building. Its majestic form is so iconic that, I have found, many foreigners actually confuse the Capitol Building for the White House. But with 13 times the floor area, and 4 times the height, the Capitol Building is far grander. It is also far more approachable. The curious visitor can walk right inside to the visitor’s center of our legislative palace, without the worry that a secret service sniper will open fire. The name “Capitol,” by the way, apparently derives via Jefferson from the Capitoline Hill, in Rome—though the connection between American democracy and Jupiter Optimus Maximus remains obscure to me. Jefferson did, however, manage to give everyone a headache when it came time to spell capital and capitol.

The Capitol was not always such a grandiose structure. The original building, completed in the year 1800, was a fairly modest affair, roughly the size of the present White House. But as the country grew in wealth, population, and number of states, so did the building have to be enlarged and expanded. The current dome—88 meters high, and 96 in diameter—was built between 1855 and 1866 (Lincoln insisted that construction continue right through the Civil War), and is actually made of iron painted to blend in with the white stone of the main structure. The two legislative chambers are now housed in the expansive wings to the north (Senate) and south (House of Representatives).

As one approaches from the west—passing the monument to Ulysses S. Grant, which marks the end of the National Mall—the Capitol presents a grandiose but inviting appearance, with two winding staircases leading up to the entrance. If one approaches from the east, however, one can see the faux-Greek temple façades, complete with sculpted pediments, such as the Apotheosis of Democracy above the entrance to the House of Representatives. The Capitol Building is also, naturally, decorated with plentiful patriotic art in its interior. Beneath the dome is the painting, The Apotheosis of Washington—a kind of heavenly scene, common in European palaces, that I always find rather silly—and below that, the Frieze of American History, a trompe-l’œil (as in, a painting that pretends to be a frieze), whose colonial imagery did not age particularly well. Both of these are the work of the Italian-American painter Constantino Brumidi, who famously fell off the scaffold and had to hold on for dear life for 15 whole minutes, until someone noticed the poor hanging artist.

But most of the people who worked on this resplendent structure were not eccentric European immigrant artists. In large part, the manual labor was performed by slaves, and the same is true of the White House. Racism runs very deep, indeed, in our democracy.

Right across the street from this most democratic branch of our government is the least: the judiciary. The current Palace of Justice is not as old as one might expect, having been completed as recently 1935. Before that, the Supreme Court had no residence to call its own, but instead had to find space within the Capitol Building. What is now called the Old Supreme Court Chamber served as the seat of constitutional law from 1810 to 1860, and the court moved to the Old Senate Chamber (itself replaced when the Capitol was expanded) until the construction of the current building. Finally, under the impetus of William Howard Taft (the only person to serve as both president and chief justice), a separate structure was built for the court.

Designed by Cass Gilbert, a friend of Taft, the Supreme Court Building is a testament to the American pretension for fancying ourselves heirs of Greco-Roman culture. The building takes the form of a Greek temple, with columns, pediment, and walls made of white marble. Two brooding statues, the Authority of Law (masculine) and the Contemplation of Justice (feminine), flank the staircase leading up to the main entrance. Above, in the pediment, is a frieze with the great theme: “EQUAL JUSTICE UNDER LAW” (they spell it out in case you miss it).

The humble visitor does not ascend these great steps to enter the court, however, but walks in through a little door at ground level, with the obligatory metal detectors. Inside the visitor center, one is presented with a monumental sculpture of John Marshall, who is often considered the greatest Supreme Court Justice ever. There are also plentiful little plaques and exhibits, and of course busts of many other justices, past and present, and a very beautiful marble spiral staircase. The visitor is permitted to ascent to the first floor, and peek into the courtroom. (The only way to actually enter, when court is not in session, is to sign up for a lecture.) Then, the visit is capped off by exiting out of the enormous, bronze doors.

As impressive as all this was, the cold dictates of justice did not touch me so nearly as the warm thrill of literature from right next door: the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress. This is but one of three library buildings in the capital, the other two being the John Adams and the James Madison memorial buildings (to deal with the overflowing collection). As an institution, the Library of Congress is impressive. With a collection of over 170 million items, in 470 different languages, the Library of Congress plausibly claims to be the largest in the world. Like any famous library worth the name, it has an ample collection of rare books and manuscripts, including one of the three perfect versions of the Gutenberg Bible still in existence. Thomas Jefferson amply deserves to be the namesake of this library, as he personally sold his collection of 6,487 books to the federal government after the invading British burned the previous collection during the War of 1812. (A subsequent fire unfortunately destroyed many of Jefferson’s books as well.)

I am a sucker for books, of course, and rather fond of ornate architecture as well. So I was absolutely delighted with the Thomas Jefferson Building. The visitor is first confronted with the busts of literary giants, from left to right: Demosthenes, Emerson, Irving, Goethe, Franklin, Macaulay, Hawthorne, Scott, and Dante. Some of these choices do seem questionable to me, however. Why a Greek orator, an Italian poet, a German dramatist, a Scottish novelist, and an English historian? And why, in this great diverse nation, no women or minorities? I propose, then, that we replace old Demosthenes with Emily Dickinson, Goethe with Louisa May Alcott, Macaulay with Frederick Douglass, Scott with Herman Melville (a white man, yes, but for my money the greatest American novelist), and Dante with Walt Whitman (another white man, though at the very least sexually adventurous). I think we have quite enough native talent here to occupy all of the busts on our own national library, thank you very much!

The interior of the building is even more richly decorated than its façade. The Great Hall is covered in an elaborate program of murals, friezes, and sculptures, created by an enormous team of artists. It is a kind of secular cathedral, with personifications of the arts, sciences, and civic life. Little cherubins adorn the grand staircases leading up to the upper deck, while heroic figures in flowing robes masquerade as abstract concepts. The names of great writers—Cervantes, Shakespeare, Milton—with accompanying quotes are worked into the decorative program, preserving something of the taste of Ainsworth Rand Spodoff, who was the Librarian of Congress at the time. All of the decoration, abstract and figurative, is lovely. The room has a light and buzzing energy, not at all oppressive in its finery. The rare books on display complete the impression of a temple of knowledge.

From the upper level of the Great Hall the visitor can peak down into the equally vast Reading Room. I must confess that, at this point, the first thing that came to mind was the second National Treasure movie. I must further confess that I was feeling slightly annoyed, as I had mixed up the Library of Congress with the National Archive, and assumed that the Declaration of Independence was displayed here. In any case, the Reading Room is quite gorgeous—filled with concentric circles of reading desks, all beneath a towering dome. Here, too, allegorical women and Great Men stand guard, including statues of Beethoven, Homer, Plato, and Newton to keep the busy scholars company. (The statue of Columbus may be somewhat less welcome nowadays, however.) Even if I were looking up the number of hairs on the underside of a flea, I think I would feel quite wise and important while doing so in such a room.

As much as I love the idea of a national library serving as an enormous intellectual resource for the nation’s lawmakers, I wonder how often members of congress nowadays make use of this temple of knowledge. One suspects it is a lot less than ideal.

I want to mention here an institution in the neighborhood that I regret not visiting: the Folger Shakespeare Library. This is an independent research organization, dedicated to the bard. Its name may be familiar from the high-quality editions of Shakespeare’s works published by the library. For any Shakespeare fans, this is the nearest thing to a mecca in the United States, as the library has the largest collection of the bard’s printed plays, as well as a theater where his immortal works are performed. Admittedly, it does seem a little strange that an institute dedicated to an Elizabethan playwright is located in the heart of our nation’s capital; but I suppose we have never been able to shake off a bit of our ancestral anglophilia.

Well, we have visited two of the branches of the federal government, so it is high time we make our way over to the third: the executive. To get to the White House from the Capitol Building by foot means walking along the most famous stretches of road in the country, a section of Pennsylvania Avenue called “America’s Main Street.” The walk takes about half an hour, and leads past a few notable monuments. One is the National Archive—which, again, I regret not visiting—and another is the monumental Old Post Office building, designed in a castle-like Romanesque Revival style. I must say, however, that Washington D.C. is not a pleasant city to stroll about, even on its most famous avenue.

Unless you contact your Member of Congress to request an official tour, chances are you will be seeing the White House from the outside, as I did. Your choice, then, is to see the presidential residence from the north or the south. The southern route takes you to The Ellipse, a large clearing in President’s Park; and from the north the spectator must gaze from Lafayette Square. This last park is the scene of much recent controversy. Presiding over the green space is an equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson, a populist and a racist, which Black Lives Matter protesters attempted to remove during the 2020 protests. The police not only thwarted the demolition, but forcibly removed all of the protesters from the area with chemical irritants, in order to give the president photo opportunity with the nearby St. John’s Church. I will let Christians decide on the righteousness of this course of action.

The White House was completed in 1800, which means that John Adams, not George Washington, was the first president to occupy this iconic seat of American power. The building owes its design to the Irish Architect James Hoban, who himself was deeply influenced by the Italian Renaissance architect Andres Palladio, who himself was deeply influenced by the Roman architectural writer Vitruvius. In consequence, the style of the White House is thoroughly neoclassical. As with the Capitol Building, the White House has two distinct façades. The northern one, facing Lafayette Square, features four columns and a triangular pediment, while the southern façade consists of six columns on a semicircular bow. It is worth pointing out that, compared with either the Capitol or the Supreme Court buildings, the White House is conspicuously unadorned. There are no statues or allegorical friezes, which I think gives the building a certain gravitas.

As presidential power gradually expanded, and the president’s entourage grew, so did the White House. The West Wing was added during the presidency of Teddy Roosevelt, in order to deal with this influx of personnel, to which William Howard Taft later added the now iconic Oval Office. The East Wing was added a few decades later, thus giving us the symmetrical structure we have today. Having toured many palaces in Europe, I must say that the White House is, at least, refreshingly small by comparison. Charles L’Enfant envisioned a palace more along the lines of Versailles; but I agree with Jefferson in thinking that such a monstrous residence would be out of keeping with a democracy. The White House is not meant to be the domain of some distant, all-powerful ruler, but our house—the seat of the people’s power.

But let us leave this fraught symbol of national power and return, once again, to the National Mall. Whereas the eastern half of the mall is dominated by museums, the western half is given over to memorials. The grandest of these is, without a doubt, the Lincoln Memorial. The memorial takes the form of a Greek temple, situated at the end of a long reflecting pool. A staircase leads the visitor past two rows of columns and into this presidential shrine, where, instead of finding an enormous Athena, we are greeted with the equally august Abraham Lincoln. He sits, regal and somewhat world weary, on a kind of throne; and the text of two of his speeches—the Gettysburg Address, and his second inaugural address—adorn the walls on either side of this national hero. Though I cannot help a little irreverence in my description, in truth I found the memorial—and especially the statue of Lincoln, designed by Daniel Chester French—to be both beautiful and inspiring. It is rare that a monumental sculpture of a politician is so compellingly human.

Standing at the other end of the reflecting pool is the World War II Memorial, which was opened as recently as 2004. Perhaps the least famous of the mall memorials, it consists of a series of granite slabs in two opposed semicircles, one per each state and U.S. territory (56 in all). The Korean War Memorial, to the south of the pool, is rather more striking in design. 19 stainless steel soldiers, in full gear, bedecked in ponchos, make their way through what is doubtless muddy ground. For my part, the sculptures strike a difficult balance between portraying the horrors of war and capturing the determination of the soldiers.

The most iconic memorial, however, is that devoted to the Vietnam War, which stands north of the pool. In design, it could hardly be simpler: a black wall that cuts a triangle into the earth, inscribed with the names of all the servicemen (and, later, some women) who died in the conflict. At the time, this design was controversial, both for its simplicity and also because its designer was an Asian woman, Maya Lin. As a compromise, a more traditional sculpture, The Three Soldiers, was placed nearby. But history has vindicated Lin’s design. Even the casual visitor cannot help but sense the trauma left by the war. Indeed, the sculpture itself was conceived as a kind of wound in the earth, which opens and then closes as the visitor makes their way from end to end. Friends and family and old comrades still leave flowers and photos besides the names of their loved ones.

Before we leave the mall, I have to mention some memorials that I did not have the opportunity to visit. They are located around the Tidal Basin, the reservoir between the National Mall and the Potomac River. One is that dedicated to Martin Luther King, Jr., which was completed in 2011. It is centered around a monumental sculpture of the civil rights leader, called The Stone of Hope (a line from King’s most famous speech), in which he emerges from a partially carved block of granite. (I should also mention that the spot from which King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech is also marked, on the steps to the Lincoln Memorial.) Further on is the Franklin Delano Roosevelt memorial, which features an open, spread out design, commemorating the 32nd president with a series of scenes from his eventful tenure. But the memorial to Thomas Jefferson undoubtedly occupies the pride of place. Like that of Lincoln, Jefferson’s shrine is a pseudo-Greek temple, with a statue of Jefferson at the center, surrounded by some notable quotes of his. Though I think the building itself is impressive, I must say that I do not care for the bronze statue of Jefferson at the center.

Well, at this point I wish I could say, “Enough with dead presidents and old wars!” But our next destination has plenty more of both: the Arlington National Cemetery. To get there, the visitor will have to leave D.C. entirely, traveling across state lines to Virginia, via the Arlington Memorial Bridge. (The bridge had been proposed since at least Andrew Jackson’s presidency, but it was not built until 100 years later. It was conceived as a kind of symbolic reunification of North and South.) Though I cannot say the walk is especially scenic, at least you get a good view of the Potomac.

Arlington National Cemetery is a graveyard with an odd history. After the Revolutionary War, the land was bought by an adopted son of George Washington, whose daughter eventually married Robert E. Lee—a man who was, himself, the leading general of the secessionists during the Civil War. In a decision that was equal parts whimsical and spiteful, the land was then confiscated to be used as a resting place for the Union soldiers who died fighting against Lee’s forces. The Supreme Court eventually decided that this confiscation was not legal, and awarded Lee’s son a very large chunk of money for the land. It does seem ironic for the government to pay someone who wanted to secede from the country for use of their land, but I suppose even rebels deserve due process.

Arlington is a military cemetery. There are very strict rules for being interred on the grounds, most of which involve having served in the military (or being the family of someone who has). With 400,000 already buried, space is naturally limited. But one can immediately see why Arlington is such a coveted spot to inter one’s earthly remains. Even if this land had not been the residence of a rebellious general, it would still be ideally suited for the task. Consisting of rolling hills that rise up above the Potomac, the cemetery provides a commanding view of the surrounding area, including the Pentagon (which sits just to the south). In fact, Lee’s old house still stands on the property, an enormous neoclassical building that was, unfortunately, closed during my visit.

The most famous person buried in Arlington National Cemetery is John Fitzgerald Kennedy. His tomb is marked by a simple black slab, which stands before an endlessly burning torch, the “eternal flame.” Nearby are buried John’s two brothers, Edward and Robert, who lay under simple crosses. Another often-visited tomb is that of Audie L. Murphy, one of America’s most decorated soldiers from the Second World War, who went on to be a movie star in later life. But most of the landmarks in this cemetery are dedicated to groups of people—mostly men—who died in tragic circumstances.

There is, for example, the tomb to the unknown soldiers of the Civil War, which stands near Lee’s old mansion. Also notable is the tombstone dedicated to the crew of the space shuttle Challenger—a moving monument, unfortunately marred by quite ugly portraits of the crewmembers on the tombstone. Most monumental of the monuments is that devoted to those who died aboard the USS Maine, which exploded off the coast of Havana, sparking the Spanish-American War. (Most likely the Spanish had nothing to do with it, but the explosion was used as a pretext for hostilities.) The monument incorporates the main mast of the ship, likely making it the tallest structure in the cemetery.

More famous, perhaps, than even the tomb of John F. Kennedy, is the tomb of the Unknown Soldier. This is a large marble vault in the courtyard of the cemetery’s amphitheater, where the unidentified remains from four American wars are interred—World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. Well, since 1998 that number has been 3, since the remains of the Vietnam soldier were identified via mitochondrial DNA and disinterred.

In any case, the bodies inside the actual tomb are meant more as symbols of the many thousands of soldiers whose remains have been lost in the fog of war. As such, they are symbolically guarded by soldiers in the United States Army, around the clock, since the year 1937. These soldiers perform an elaborate ritual of pacing back and forth, snapping their rifle from soldier to soldier, in a series of actions so precisely timed and coordinated that it seems scarcely human. It is hypnotic to watch; one wonders at the amount of training that must have been necessary. Every hour or half-hour (depends on the month), the guard is relieved of duty in an equally elaborate ritual, known as the Changing of the Guards, in which the rifle is presented to the next guard on duty.

Now, here I am, at the end of a long post about the capital of the United States of America. And I am afraid that it has all been rather stuffy and dreary. Virtually all that makes Washington D.C. notable has to do with politics or war (which is, of course, just politics by other means). In other words, it is a city given over to monuments, memorials, and museums—beautiful, grandiose, and dead. Apart from these attrctions, the city center is mostly comprised of governmental offices, filled to the brim with bureaucrats, lawyers, administrators, clerks, officials, aides, and of course politicians (aside from all the tourists). This gives the city a curiously alien feel, as if it exists for nobody in particular—like an office full of disaffected workers. Even the shops and restaurants reinforce this impression, as the vast majority are chains and franchises, equally devoid of character.

So, to end this post, I would like to focus on a bastion of life in our nation’s great capital, a little takeout place called the Greek Deli, located right in the center of D.C. Its owner, Kostas Fostieris, has been working in this cramped little shop for over 30 years, beginning his workday at 3 in the morning. He was still going strong when we visited, September of last year. The deli serves an assortment of typical Greek staples: gyros, soups, hummus, salads, feta cheese, and so on. What makes the place so special—aside from the food being so very delicious—is that it is absolutely unpretentious. There is nothing trendy about the place; there is little outdoor seating, and there is no way to order via an app. Indeed, the deli is not even open on the weekends. Instead, the visitor must queue up, order from Fostieris himself, and then hope there is a spot to eat in one of the tables outside.

Explained in such a way, perhaps the deli does not sound so appealing. But in a city like D.C., it is a godsend. This was the one time during my whole visit that I felt like I was in a real place, filled with living people, people who were laboring, loving, and growing old in this chosen spot. This is the feeling one gets from any genuine community—and it is a feeling horribly lacking from the capital, or at least the city’s center. And, let me add, the story of a Greek immigrant struggling night and day to make his little shop a miniature institution is just as American as the Lincoln Monument. For my part, Kostas Fostieris is an American hero. At the very least, he has likely brought more joy into the world than many who have served inside the Capitol Building.

I am sure that is a lot more to D.C. than what I saw during my short visit. My only hope that there are enough pockets of life like the Greek Deli to help compensate for the sterile deserts of jingoistic vainglory that so dominate Washington. During my visit, I felt that the entire city epitomized the emotional distance between the ordinary citizen and those at the country’s helm—as if our politicians were the equivalent of the guard of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, enacting a stiffly ritual preservation of the illustrious dead. But, as Jefferson noted, “The earth belong always to the living generation.” This is why politics, at its best, shares the same goal as any great human endeavor: to touch people. And I cannot think of any better way of doing that than a delicious lamb gyro.

I’m on the Radio, again!

Back in June, I was interviewed for the radio station Santa María de Toledo. The host, Teresa Martín Tadeo, apparently enjoyed the interview enough to ask me to do another one. This time we talked about Thanksgiving traditions (the holiday isn’t celebrated here, so Spaniards are always curious), as well as the recent elections. I hope you enjoy!