It was a thoroughly muggy day in mid-August when I boarded a boat in Battery Park.

My destination was the most famous statue in the United States, if not the world. And I was willing to pay to get up close. Now, if you merely wish to take a good picture of the statue against the New York City skyline, then no financial transaction is necessary. The Staten Island Ferry—a gratuitous vaporetto—passes quite near Liberty Island, allowing its parsimonious passengers an excellent vantage point from which to gawk and snap photos. But I was in no mood for drive-by glances; I wanted to see the statue from dry land, which requires a certain amount of money.

In the time before COVID-19, the ferry company had no qualms with herding us through a large security tent and then packing us into the boat like salted fish. I opted to stand on the deck. Despite the summer heat and the humidity, the sea wind whipped up soon after we set off, giving me goosebumps. But this was compensated by anticipation. Even a short ferry ride partakes, however modestly, in the romance of travel by sea. And as a good friend of mine once said (well, he said it repeatedly): “The best way to see a city is by boat.” This is certainly true regarding New York City, at least. Seen from the harbor, the Manhattan skyline is at its most vertiginously dramatic. The Statue of Liberty is not bad, either.

In about twenty minutes the boat docked at Liberty Island. Now, this was not always the name of this little piece of earth. Before Europeans came to dominate the land, the Canarsie people called it Minnisais. Since then, however, the island has been dubbed Love Island, Great Oyster Island, and Bedloe’s Island, among other appellations. It had many uses before being made home to an enormous copper goddess. Food was grown, men were hanged, garbage was dumped, and Tories waited here to be extracted to England. The island was even used as a kind of lazaretto for those suspected of harboring smallpox. Its last function before being turned into a monument was as a fortified battery; and the star-shaped remains of Fort Summer still sit below Liberty’s green heel.

I pushed my way down the boarding ramp and headed straight for the statue. This was not my first visit. Many years ago, when I was still in middle school, I visited the island with my Californian cousins, who wanted to see some of the main sights of New York. At the time I was inclined to see any sort of cultural excursion as a monumentally boring waste of time. Video games were infinitely more entertaining, and I resented my family for dragging me away from my computer. Nothing I saw made much of an impression on me: not the Empire State Building, not Wall Street, not Battery Park. It was wholly unexpected, then, when I found myself entranced by the Statue of Liberty. I could not take my eyes off it. I even felt inspired. Somehow the statue had broken through the many layers of youthful apathy and juvenile ignorance to touch a hitherto unknown part of myself.

This second visit was not quite as stupendous, if only because by this time I had grown accustomed to visiting monuments and the feelings that they evoke. This is not to say that I was uninspired. The towering lady is not as dynamic in composition or as beautiful in form as, say, Michelangelo’s David; and the sickly green color (caused from the oxidation of the copper) is not the most aesthetically pleasing shade imaginable. (Like the oxidized patina itself, however, it grows on you.) But statues of this size have different engineering constraints, not to mention serving a different purpose. As a synecdoche of the nation, as a grandiose welcome to those arriving by sea (many of them immigrants), and as an artwork that represents the Enlightenment values that (nominally, at least) set this nation apart, Liberty Enlightening the World could hardly be more successful. Granted, Bartholdi probably only intended some of this in his design; yet the mark of any great work of art is that it goes beyond even the vision of its creator.

I had opted for the cheapest ticket, which only allowed me to gaze at the statue from without. Paying more would have given me access to the pedestal, and still more would have allowed me to ascend to the seven-pronged crown. (Visits to the torch have been prohibited since 1916, for a somewhat obscure reason.) But even the most basic ticket seemed pricey to me. So after I had taken my fill of the statue, and walked around her a few times, I wandered over to the other end of the island to see the museum. The visit begins with a strange cinematic experience, wherein visitors are led into a big, empty room, shown an informational video about the statue’s history, and then led into another room where the video continues, and then yet another. I suppose they screen the film this way so that more visitors can be shown it at once, though I did wish there were seats available.

The museum in general was surprisingly good. There are models of the statue and its innards, a great deal of information about its construction and inspiration, and even real models and former parts. But rather than try to narrate the museum, I will use it as an opportunity to tell something of the statue’s history:

Given that Lady Liberty is one of the most quintessentially images of America, it is somewhat ironic, then, that the statue was designed and built entirely by the French, and given to us in an act of international generosity. I can think of no other major monument with such an origin.

The idea for a celebratory dedication to the United States evidently originated with Édouard René de Laboulaye, a prominent French abolitionist, who wished to celebrate the Union victory in the Civil War, and the end of American slavery. This proposal was taken up by his friend, the artist Frédéric Bartholdi, who liked the idea, if only because it would have provided an indirect rebuke to the repressive regime of Napoleon III. But such projects are seldom conceived and completed on schedule; and by the time the statue was finally built, in 1885, Napoleon III had been deposed.

It was difficult enough for the cities of Brooklyn and New York (when they were formally separate) to work together to plan, fund, and execute the Brooklyn Bridge across the East River. Imagine, then, the nightmare of coordinating an international project across the Atlantic. To build the statue, Bartholdi had to personally come to the United States, scout out a good location, meet with the president (Ulysses S. Grant at the time), and then cross the young nation trying to drum up support. Batholdi also had to come up with a design. That the theme should be liberty was obvious; but freedom can take many forms. It can be a bare-chested woman leading troops into battle, à la Delecroix; yet that seemed too violent or revolutionary. Instead, Bartholdi opted for a neoclassical design, staid and solemn, robed in a Roman stella (togas are for men), crowned with a diadem, and holding a torch rather than a sword.

In 1875 Bartholdi and Laboulaye set to work raising money for the statue. It was to be a long slog, combining a difficult PR campaign with a vast logistical challenge. Building material was needed, talent had to be recruited, and the public interest maintained at a high enough level to keep funds flowing. As an engineering task, the statue was daunting enough. Standing 46 meters tall, the statue had to support 91 tonnes of metal without crumpling or toppling over. The thin copper skin simply would not bear that much weight, and so Gustave Eiffel was contracted to design an internal steel skeleton. This internal work is a magnificent achievement in itself, since it could be easily assembled and disassembled, and also because Eiffel designed it in such a way as to allow the metal to expand and contract in the changing weather without cracking the skin. Were the copper exterior removed, then, New York would have her own Eiffel Tower.

While the French were busy with the statue, the Americans had to make the pedestal. This proved to be quite a challenge, for the simple reason that nobody wanted to cough up the money. Grover Cleveland—who was then the governor of New York—vetoed funding for the statue, which left the project lingering in unfunded purgatory. (Cleveland, as president, later presided over the dedication of the statue, which seems terribly unfair.) The task to fund the project fell, instead, to private industry and the good people of New York. Specifically, Joseph Pullitzer led a funding drive in his newspaper, The New World, promising to publish the name of every single contributor. Thus the pedestal was built with spare nickels, dimes, and pennies, mailed in from children, widows, and alcoholics. Even so, it took longer than expected to raise the required sum, and the pedestal was still incomplete by the time the statue arrived by steamboat.

The assembly and disassembly of the statue, transportation across the seas, and then reassembly in its new home, was yet another massive engineering challenge for the designers. Eiffel’s steel beams arrived with Bartholdi’s hand-beaten copper, and teams of workers had to put it all together, like an enormous erector set. The statue’s completion was celebrated by the city’s first ticker-tape parade, which culminated in a yacht trip to the island for a private dedication ceremony, attended only by politicians, dignitaries, and other officials. Ironically, in a fête for an enormous female, few women were permitted to attend. The values of the Enlightenment have their limits, after all.

My sojourn on the land of liberty had come to close; but I still had more to see. Tickets to visit the Statue of Liberty come included with a trip to Ellis Island, just a few minutes away. Like Liberty Island, this island used to be called Oyster Island, for the very logical reason that it was a shallow tidal flat where oysters liked to live. As such, it was used as an important food source by the Lenape people, but they called it “Kioshk” for the many seagulls which liked to rest there. Much later, when an island was needed to process the increasing tides of immigrants, the government started dumping sand, rocks, and soil (taken from the subway tunnels) in order to create something fit for permanent habitation. (This had very unfortunate results for the oysters, which scientists are now trying to revive in the Billion Oyster Project.) Ellis Island was not even originally a single island, but three separate ones which were gradually merged. The current landmass is shaped like a fat “C,” and ships dock in the space between the northern and southern halves.

Ellis Island has come to serve as a symbol of American immigration, but of course this particular institution represents only one chapter of the story. Ellis Island was never the only port of entry into the United States for immigrants, and it was active for only about thirty years, from 1892 to 1924. Most of these immigrants coming through Ellis Island were, naturally, from the other side of the Atlantic, specifically Europe. This includes Germans, Irish, Scandinavians, a great many Italians, Eastern European Jews escaping pogroms—and many more, to the tune of 12 million souls. It has been calculated that 40% of the United States population can trace at least one ancestor to Ellis Island (though I do not know if that includes me).

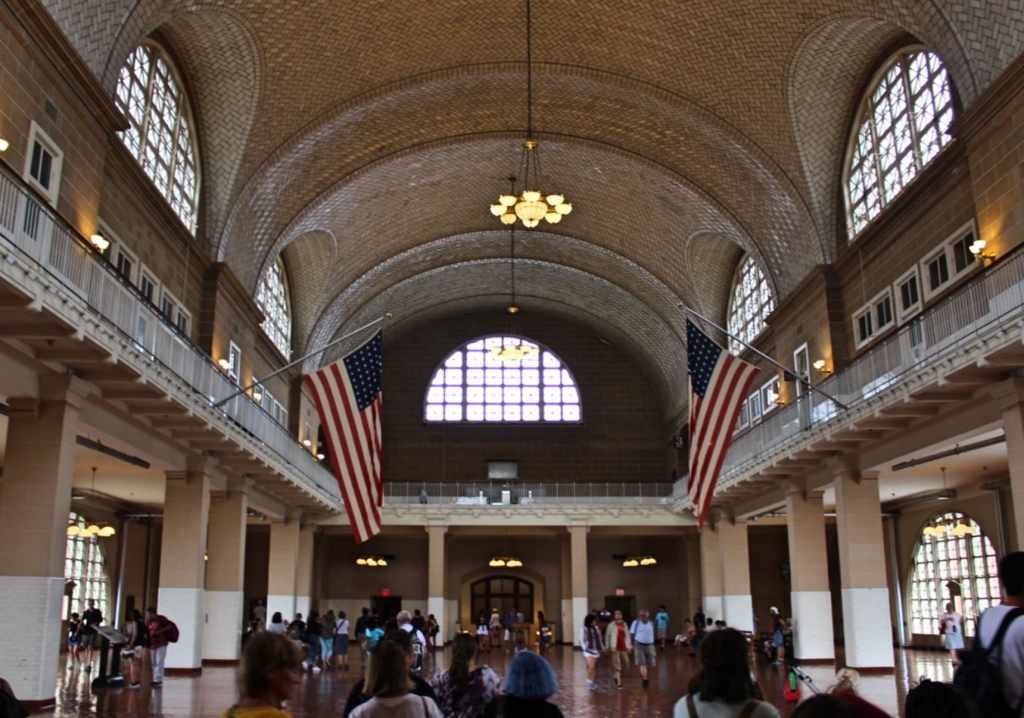

The basic visit is to the island’s Main Building. This is a large and surprisingly beautiful structure, built in a French Renaissance style. Your visit is meant to replicate the journey of an arriving immigrant to the island. You begin in the baggage room, complete with real period suitcases and trunks, where you pick up your audioguide. Then you advance to the registry hall, a cavernous open room topped with Guastavino tiles, which shimmer and sparkle in the indirect light. But I doubt that an arriving immigrant would have been in the mood to admire architecture, since this room was the scene of fateful decisions.

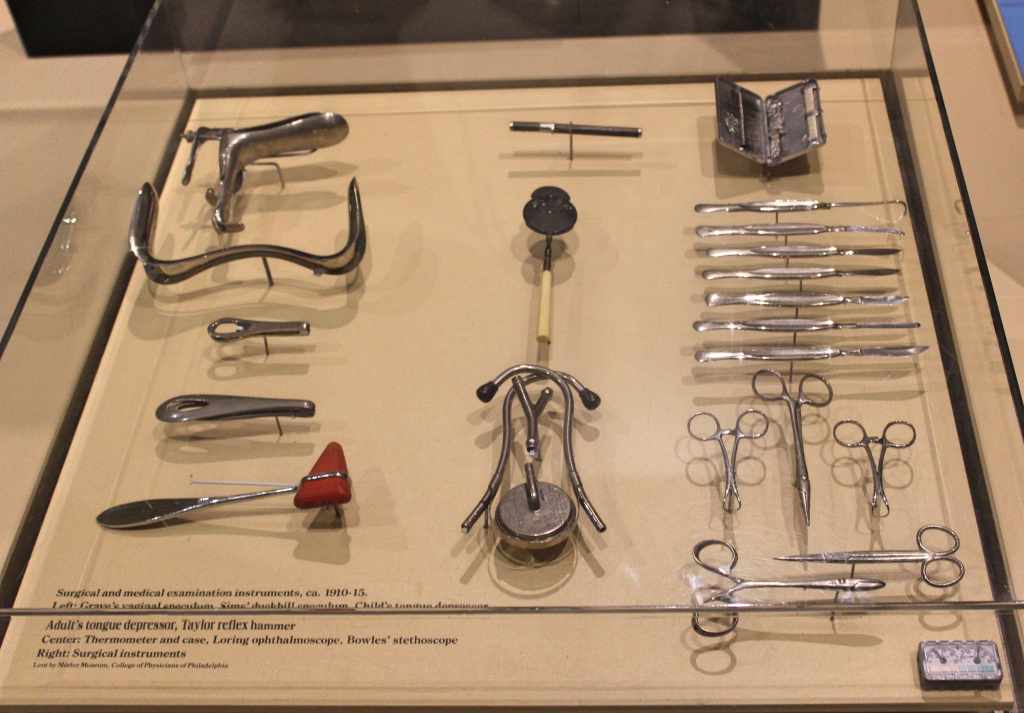

While the hall is now open and luminous, during the heyday of Ellis Island it would have been full with queues upon queues of incoming immigrants, awaiting their turns on long benches to talk with a customs official. While they entered and waited, doctors would inspect and examine the hopeful immigrants for any signs of ill health. Those presenting a worrisome sign would be marked with chalk and more thoroughly examined. If the problem was grave, or the disease highly contagious (like trachoma, an eye affliction), the poor soul might be sent all the way back—a fate of a small minority (about 2%), but a very crushing fate indeed after spending one’s savings and crossing an ocean in the hopes of a new life. If the problem was less severe, then the migrant may be in for a stay at the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital (more on that later).

In any case, even for the well in body in mind, the experience must have been extremely stressful. For the most part, the rich are not the ones who emigrate; it is the poor, with little money to spend. Consequently, then, the voyage aboard the steamers crossing the Atlantic was abysmally uncomfortable—cramped, cold, dark, seasick and poorly fed. Then the storm-tossed travelers were thrown into a hall echoing with unintelligible languages to be handled by unfeeling officials.

Thankfully, for the majority of those arriving on Ellis Island, the affair was quite short, lasting only a matter of hours before they were allowed through. Laws regarding immigration were, after all, far more lenient back in the day, especially in the decades leading up to World War I. Stefan Zweig, for example, remembers traipsing around Europe without even possessing a passport. But that war initiated a period of nationalism and xenophobia on both sides of the Atlantic. A literacy test was mandated in 1917 (in the immigrant’s native language), and by the 1920s quotas were imposed, thus ending the period of mass immigration.

From the registry hall, you move from room to room, each one used to process the immigrant in a different way—further health inspections, mental aptitude tests, literacy tests, legal processes, money exchanges, bus tickets, and so on. A courtroom was busy hearing cases of immigrants suspected of being professional paupers or contract laborers (oh, the horror!); luckily, immigrant aid societies paid for lawyers to help appeal cases, and 80% of the immigrants on trial were accepted. Particularly fascinating to me were the examples of IQ tests, meant to weed out those considered to be mentally infirm or deficient. This was a challenge, since the tests had to be applicable to anyone, regardless of their national background. Even a simple task, like drawing a diamond, was not a fair measure, since a large portion of immigrants had never even held a pencil. The psychologists thus settled on visual tests, like identifying faces or distinguishing between images. Still, the whole attempt seems rather silly in retrospect.

To repeat, for the majority of immigrants, Ellis Island was only a brief stopover. But a sickly minority required a longer stay—days, weeks, or even months—in the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital. For some, this meant a stay to “stabilize” their condition before being sent back, but for others successful treatment was an entry ticket to another life.

The hospital is on the other half of the island, and off limits to the casual visitor. To go, one must sign up for a guided hard-hat tour, as the buildings are nowadays in a quite dilapidated condition, empty and overgrown. But at one time this was one of the biggest public health hospitals in the world, complete with separate words for infectious diseases. Nowadays, in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, we can appreciate the role of border control in controlling contagious illness. This idea was old even by the time Ellis Island was built (there are islands for isolation in the Venetian lagoon, for example), though of course it was never a fool-proof way of controlling epidemics—such as the waves of cholera that arrived from the Old World. Still, Ellis Island was an important line of epidemiological defense for the United States.

Taken together, the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island are the country’s greatest monuments to the immigrant—symbols of the country’s open-armed embrace of anyone willing to come. At a time when anti-immigrant sentiment is once again raising its ugly head, these monuments are more important than ever, for they remind us that the majority of us are descended from immigrants, most of them poor, most of them uneducated, and all of them looking for a better life. How were those Hungarians or Italians, unable to write or even to hold a pencil, any different from the people now at our southern border, who fill us with so much fear?

Economists may show us, again and again, that immigrants do not steal jobs; and historians may demonstrate that xenophobia is used, again and again, as a scapegoat for other social ills. But no argument is as profoundly moving as that lady of oxidized copper, herself an immigrant, holding out her torch towards the vast and windy seas, inscribed with the words of Emma Lazarus:

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Your ancestors did not come through Ellus island. By 1897 we were already three generations here. Adam..Reuben..Albert..

Robert…Norman…Roy..

This is a great piece…I always loved the museum..originally done by Hallmark!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I knew the male Lotz line didn’t, but there are an awful lot of maternal lines that I haven’t traced.

LikeLike