The word puente has two meanings in Spanish. Most commonly it simply means “bridge.”

But it is also the word for an extra day off given when a holiday falls in-between a weekday and the weekend. For example, December 8, 2015—a Tuesday—was a holiday; and as a result I got the preceding Monday off. (This holiday, which comes every year, is called the Día de la inmaculada, a day dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Unlike in the US, most holidays in Spain are religious—specifically, Catholic.)

In short, it was time to go to Seville.

But how to get there? Before I came to Spain, everyone told me that flying in Europe was remarkably cheap; but every flight to Seville I found was annoyingly pricey. How about the high-speed train? This was even worse. What, then?

“How about Blablacar?” someone recommended, as I vented my frustrations.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“It’s a ridesharing service. It’s like AirBNB, except for car rides. You pay the driver and then go together. It’s quite cheap.”

“Hmm, interesting.”

“And it’s a good way to practice Spanish, too, since you can talk with the driver. I’d recommend it.”

(As a side note, I have since used Blablacar dozens of times, and I have had nothing but good experiences. Though I was at first concerned for my safety—getting into a car with a stranger—the identity checks and the system of reviews on the site make it quite safe. And besides, what other ways are there of forcing a Spanish person to talk to you for hours on end?)

§

When you take the usual dross material of small-talk, and then throw in the difficulty of communicating in a language you hardly know, the end result is pretty stale conversation. Our poor Spanish driver had thus to deal with five hours of slow and painful attempts by me to be personable and interesting, while I fumbled for words and made a mockery of grammar.

Many hours after I had reached the full extent of my Spanish ability, we reached Seville.

Seville is a city with a long past and a bright present. Populated at least since Roman times, the city grew into a prosperous power under the Moors, who controlled the city for about 500 years—until, in 1248, the city was conquered by the Christian king Ferdinand III of Castille.

The city is 80 km (50 miles) from the Atlantic Ocean, crowded along the banks of the Guadalquivir River; and Seville’s harbor is the only river port in all of Spain. This port on the Atlantic Ocean gave Seville a huge economic advantage when Spain began the age of colonization in the New World—an economic dominance which lasted until the 17th century, when silting rendered the port unusable, thus leading to the ascendence of Cádiz (though by this time Spain was economically in decline).

Though not as dominant as it was in the past, Seville is still a thriving place. The fourth largest city in the country, with a population of about 700,000, the city is also the capital of all of Andalusia. It is also the metropolitan area with the highest average temperatures in all of Europe—its summer highs only exceeded by nearby Córdoba. Culturally, too, Seville is extreme: its massive Holy Week processions are internationally famous, as is the city’s raucous annual festival.

Our first stop was the cathedral. The Cathedral of Seville, Santa María de la Sede, is one of the largest church buildings in the world. Indeed, when it was first built it surpassed the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, which had held the title of the biggest church for the previous 1,000 years. The cathedral was built on such an enormous scale as a way of celebrating the Christian reconquest of the city from the Moors, back in 1248, as well as the city’s growing wealth. According to an old tradition, the cathedral chapter wanted to build a cathedral “so big that those who see it think we are insane.”

Despite all this, I must say that, from the inside, the cathedral did not feel noticeably bigger than the other cathedrals I have been in. All of them are fairly gigantic.

In any case, the Seville Cathedral is not only big, but is one of the finest in the country. The cavernous space, populated by a forest of columns that branch into elegant ribbed vaults, is spacious and bright. The choir, the organ, the chapels—everything has been decorated with extreme skill and unfailing taste.

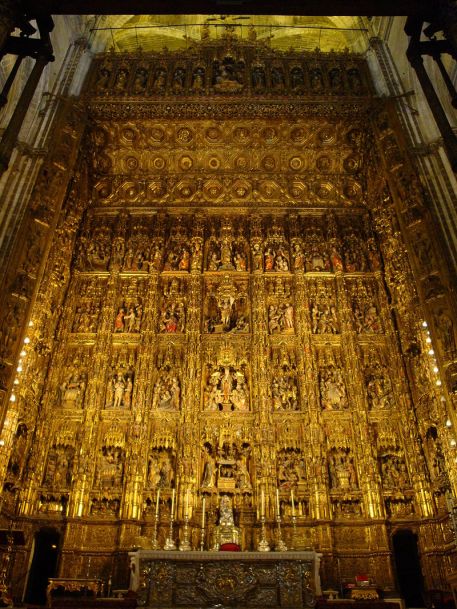

Even among this embarrassment of riches the main altar stands out. Like the cathedral itself, it is absolutely massive: 20 meters (66 ft) in height, 18 meters (59 ft) wide, and divided into 28 scenes of the life of Jesus and the Virgin Mary. Considered among the finest altars in Christendom, this piece was designed by Pierre Dancart, and took fully 80 years to complete (by which time Dancart had long since died). The audioguide remarked that the altar can be thought of as a gigantic visual theological treatise, though perhaps calling it a visual Gospel would be more accurate. Several hours would be necessary to properly examine the whole work, savoring every scene and detail. As it was, I could only gape stupidly at the big hunk of finely decorated gold for a few minutes before moving on.

I do remember being somewhat disappointed with the audioguide. The visit took us to every small chapel in the cathedral—and there are many—directing us to look through the grilles at the altars and tombs inside, as the narrator simply listed off individual object therein. I would have appreciated more information about selected pieces rather than a catalogue. In any case, according to the guide the cathedral possesses one of the most important collections of religious paintings in all of Spain. Unfortunately this collection is difficult to appreciate, as—peering through the bars of the grille like a prisoner, squinting from 15 feet away—you cannot get a good look at most of the paintings.

So I was a bit bored by the time I circled through half the cathedral, and found myself standing in front of an impressive statue of four men holding a coffin on their shoulders.

“This is the tomb of Christopher Columbus,” said the guide.

I froze. This is an excellent example of what I call “European Travel Syndrome.” Let me explain. It is sometimes easy to forget that you are traveling in Europe. On a car, a train, a city street, often surrounded by other American tourists, you could be at home. But sometimes the reality that you are in Europe—the place which you spent so long learning about in school, the place where Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, and Napoleon performed their famous and infamous deeds—brings itself to your attention so forcefully that it nearly knocks you down.

This was one such occasion.

Most of the time, historical personages like Columbus are little different from fictional characters. We hear a few stories about them, stories which purportedly explain some facet of the present world; but really they remain shadowy figures in our imagination, in the same realm as Santa Claus and Huckleberry Finn. But here were Columbus’s bones.

I was staggered. It is not that I have any particular love or respect for the man—from what I’ve heard, he was horrid—but it was simply the shock of having an erstwhile figment of my imagination become a flesh-and-blood individual right before my eyes.

It’s worth noting in passing that Columbus’s remains roamed nearly as much as he did. They were first interred in Spain, first in Valladolid and then in Seville. Then they were moved to the Dominican Republic, and then to Cuba, and then finally back to Spain again. The man was well-traveled.

Columbus’s bones notwithstanding, the highlight of the cathedral is without doubt the Giralda. This is the cathedral’s famous and lovely bell-tower. It owes its form to two cultures: originally a minaret constructed by the Moors, the Christians later added a Renaissance-style top to the edifice, leaving the Giralda with a unique juxtaposition of styles. The result, however, is a beautiful structure, which stands nobly over the surrounding area, its tan façade shining brightly in the Andalusian sun. The tower’s 105 meters (343 ft) are topped with a statue (known as “El Giraldillo”) of Faith triumphantly lifting a cross, designed by Hernán Ruiz. (A copy of this statue greets visitors on their way inside the building.)

Though the Giralda is tall, the climb to the top is not so bad. This is because there are not any stairs. Rather, dozens of ramps lead the pilgrim gently up and up, without having to break a sweat. The original purpose of these ramps, by the way, was to allow people to ride their horses up to the top, which sounds like great fun to me.

Like the Empire State Building, the top of the Giralda is always crowded, with people jostling for space, squeezing into every spot with a view. I joined the contest, nudging and elbowing my way to a good spot. It is worth the struggle, for this is undoubtedly the finest view in Seville. You can see for miles and miles, all of Seville stretched out before you with its rows of white buildings glaring in the sun, so bright that it was hard to look at them.

The visit ended in the Courtyard of the Oranges—which, as the name implies, is a courtyard full of orange trees. This is typical of Seville: there are orange trees everywhere, in every park and alongside every street. Several times I considered plucking one of these oranges, but thought better of it when I noticed that nobody else was doing so. Perhaps there’s an obscure sevillano law forbidding it. Regardless, I’ve never seen fruit trees just sitting around a town like that, completely laden with ripe fruit. Don’t the oranges eventually rot and fall into the street? Do they have government employees dedicated to cleaning up all the fallen oranges? Are they ever harvested? These are the questions that keep me up at night.

§

In a rare spasm of foresight, I did a bit of research and bought tickets to a flamenco show before arriving in Seville. Andalusia is known for its flamenco; and being a longtime fan of Paco de Lucía, I simply had to see a show.

So after a stroll around the city, across two bridges which spanned the Guadalquivir river, we found ourselves in a cozy room filled with folding chairs—not more than thirty, I’d say—the walls covered in sundry Spanish guitars, sitting before a stage. The show was about to begin.

A young man with a full black beard, dressed from head to foot in plain black clothes, climbed onto the stage and sat down. He was the guitarist. As soon he began I could tell that he was excellent. Like all flamenco guitarists, he played with his fingers, not a pick. The nails on his right thumb, forefinger, middle finger, and ring finger were filed into impressive knife-blades, with which he plucked, strummed, tapped, and flicked the strings. Most of the interesting guitar-work in flamenco is done with this hand. The guitarist picked out complex arpeggios and sustained notes with a rabid tremolo, his fingers so precise that they seemed more like machines than human appendages.

But there was nothing mechanical about the music. The first song was in a free rhythm. It began in a whisper and ended in a roar. The harmonies used in flamenco are not the sweet and dulcet harmonies often heard in, say, classical guitar. Rather, they use (among other things) a lot of parallel octaves and fifths, which gives the chords a strong, striking, and slightly sour sound.

Partly as a consequence, there is a certain emotional flavor associate with flamenco music that I find hard to put into words. As in American blues, in flamenco sadness is the fundamental emotion of the music, and the problem to be dealt with. But whereas blues deals with melancholy using a winking ironic, in flamenco the response is passionate melodrama. The emotions are mastered, paradoxically, by pushing them to the limit of intensity. Thus there is something grandiose, even ostentatious, about flamenco; it is as if one must puff oneself up with pride before performing.

The show went on. The guitarist shifted to a faster tune, showing off his rhythmic chops. A man joined him on stage for this song, wearing leather shoes with high heels, who stomped and clapped as accompaniment to the guitarist. But in addition to being the drummer of sorts, this man was the singer; and for the next song he stood up, walked to a corner of the stage, and raised his chin into the air as he prepared to sing.

His voice was incredibly loud—almost painfully so. In flamenco, the goal of the singer is neither melodic flourish nor sweetness of tone, but intensity. To this end, the singing is done with the back of the throat, producing a thick, husky timbre, surging with energy. The result is extremely expressive; it is as if you are not merely hearing the sound, but being pummeled with it.

Next came the dancer. She was a young woman, wearing a bright dress. Before she began, she arched her shoulders back and looked straight out across the audience, her face scrunched up in an expression of both pain and the contempt of pain. She seemed somehow too giant for that tiny room and that miniscule stage. Her squinted eyes looked past audience and even the walls, penetrating far beyond.

The dancing began. She was wearing high-heeled shoes similar to the singer’s, which allowed her to use her feet as drumsticks to pound on the floor. It was staggering how quickly she could move her feet, sounding like a snare drum as she crossed the stage from right to left, left to right, creating a sound so tremendously loud that I considered plugging my ears with my fingers.

Soon I was completely absorbed. My sense of time disappeared; I was so involved in the sound, my entire attention focused on the little details of timbre and ornament, that no concentration was left for anything else. I forgot everything: where I was, who I was, even that I was anything at all—my mind so awash in notes and rhythms that, for all I knew, my whole life up until that point might have been a silly dream.

By now I was sitting on the edge of my seat, my feet tapping of their own accord, my heart thumping, my skin covered in goosebumps, the hair on my arms and legs standing on end. The singing was so loud, the rhythm so fast, the guitar playing so intricate, that the whole effect was overwhelming. It became as physical as it was mental, as if the sounds were reaching across the room and shaking me in my seat.

My mind started to race. Thoughts popped in and out of my head, new thoughts, strange thoughts, memories, hopes, dreams, fears, vague longings, all colored with ecstatic shades of excitement. I felt timeless and invincible; I felt that nobody has ever been so inspired or so creative. The world around me took on a new glow, and I saw and heard everything for the first time. Mad confidence surged through me: I

And then the music ended, my heart rate slowed, and I became tired and groggy, like I just woke up from a troubled sleep. I walked from the venue into the cool night air, which brought me back to my senses. Like all great music, the flamenco had lifted me into a heightened state and kept me there, refreshing my spirit in the process.

§

Because one day of the puente was taken up visiting Córdoba (an easy day trip on the train), we only had one more day to see Seville.

It was time to visit the Alcázar of Seville. Now, there are “alcázars” all over Spain. This word (as do many Spanish words that begin with “al-”) comes from Arabic (“al-” is just the word for “the”, and “cázar” comes from “qasr”, meaning palace, castle, or fort). After the Moors were banished from Spain, several impressive castles and forts were left behind, which the Spanish Catholics happily repurposed. The Alcázar in Seville is one of the most famous of these, and justly so.

After a long line that thankfully moved quickly, we had passed through the front gate—the Puerta del León, named for the painting of a grotesque lion, wearing a crown and holding a cross, which sits over the entrance—and had arrived inside.

The Alcázar of Seville is among the most fascinating building complexes in Spain. Gothic, mannerist, baroque, and mudéjar styles are crammed up next to each other, as different sections of the palace were completed in different phases of history. The most famous section of the palace is the mudéjar palace. Though the palace’s history dates back to the Moorish period, this palace was built under Peter I of Castille, a Christian king who hired Muslim artisans to construct a palace similar to the Alhambra in Granada, which had been built just 20 years before. This building is thus a testimony to the deep cultural exchanges between the medieval Christians and Muslims.

As a side note, the Alcázar is still a royal residence—where the royal family stays when they visit Seville—thus making it the oldest active palace in the country.

The intricate Moorish architecture, with its finely carved floral designs, its sweet blues and subdued sand-colored walls, its elaborate wooden and gilded ceilings, gave the structure a gentle nobility far removed from the ostentatious grandeur of the gothic architecture of Seville’s cathedral. Every surface of every wall was covered with complex designs: arabesques, calligraphy, and colored tiles running along the lower half. Horshoe archways (which the Moors copied from the Visigoths) separated chamber from chamber. Within was an open space, the Courtyard of the Maidens, containing a rectangular pool of sky-blue water.

The most impressive room in the entire palace is the Salón de embajadores, or the Ambassador’s Salon, which is covered with a golden dome that has been ornamented with intricate geometrical designs. The adornments on the walls, too, are sumptuous and remarkably fine. One of the only reminders that this palace is not the Alhambra itself are the insignias of Castille and León which can be seen inserted into many of the designs.

Another clue are the floor tiles that contains the words Plus Ultra. This phrase is a reference to the phrase ne plus ultra (“not further beyond”), which was applied to the Strait of Gibraltar—believed in previous ages to be the limit of the navigable world. Columbus, sailing for Spain, proved this to be wrong, and thus the Spanish Coat of Arms contains the phrase “further beyond”: Plus Ultra.

There is also a gothic palace in the Alcázar. Compared with the mudéjar palace, this one looks rather shabby—some of the decorative tiles have even been installed incorrectly. But it does contain some excellent tapestries with images of old maps.

Beyond the palaces are the gardens. These are marvelous—and enormous, covering 60,000 square meters (about 15 acres), and containing more than 170 species of plant.

Tiled walkways cut through enclosures of big-leafed shrubs; tiny aqueducts lead from fountain to lazily bubbling fountain; palm trees jut into the air, towering high up above. It is very easy, and very pleasant, to get totally lost amongst the winding paths and tall trees. Suddenly you are not in a busy city, surrounded by tourists and street performers, but someplace far away, someplace quiet and green. It was lovely.

But we couldn’t stop and smell the palm trees; our time was running short. So, after just a half hour, we pulled ourselves from the garden and made our way to the Plaza de España.

This plaza lies in the heart of the Parque de María Luisa, the loveliest park in the city. Both this park and the plaza owe their current form to the Ibero-American exposition, a world’s fair held in Seville in 1929. Thus, unlike other plazas de España in Spain, Seville’s Plaza de España is not a city-square at all, but a massive exhibition space and architectural showpiece.

A fountain sits at the center of the large open space, embraces by a sprawling, semi-circular edifice. This structure was built in the Neo-Mudéjar (Moorish-Revival) style, and consists of a central building with two towers on either end, connected by curved wings. Separating the fountain area from the building is a moat, spanned by several bridges; and if you pay a price, you can rent a little row-boat and row around this artificial river. I didn’t do this myself, but the rowboats certainly added to the charm of the place.

Beyond the bridges, attached to the building’s façade, are rows of elaborately decorated benches. Each of these is dedicated to a specific Spanish city, and has a famous historical event depicted in colorful marble on the back. The cities were arranged alphabetically, making the Plaza de España a true celebration of Spain and all its history.

“Let’s take a picture in front of one of these,” GF said.

“Fine,” I said, and began to sulk. For whatever reason, I loathe the idea of bothering strangers to take a picture of me. First, I think it’s a silly reason to interrupt someone else’s vacation; and second, I have this reoccurring fantasy that as soon as my phone is handed over, they’ll just bolt with it.

In any case, we asked an elderly couple to do the honors. This little interaction led to a conversation—during which I learned that they were Germans, and that the husband was very displeased with Spain’s upkeep of its monuments. “They don’t clean anything here,” he said, and then went on to comment on the abundance of “black money” (money kept off the books) to be found in the country. They were Germans, all right.

§

Our last stop was the Metropol Parasol. This is a gigantic wooden structure that looks like a bunch of mushrooms sticking out of the ground in downtown Seville. Indeed, in Spanish it is known as Las Setas de la Incarnación, “Incarnation’s mushrooms.” This structure, which boasts to be the largest wooden structure in the world—judging from this and its cathedral, Seville has a preoccupation with largeness, it seems—was designed by Jürgen Mayer, a German architect, in 2011.

After another line (the omnipresent plague of holiday-makers), a three-euro fare, and a ride in a snazzy elevator, we were up at the top of the thing. A twisty passageway led from the elevator to the main platform. The view here was excellent, nearly as fine as the view from the Giralda. The sun was just setting, lighting up the horizon in a faint carmine glow, while the rest of the overcast sky was a dull bluish gray hanging lazily above us. A nearby church tower split the view of the city into halves; and beyond we could see the cathedral, standing proudly over the city streets. And as I looked out over the city of Seville, I could not help feeling the faint tug of melancholy, for our wonderful weekend had come to a close.

Our trip ended at a restaurant on the Guadalquivir river, eating tapas and watching the ferries go by. The lights from the boats and the bridges shimmered off the water, making the ground and sky melt into one another. Our waiter happily welcomed us to our seats, and then promptly forgot us—which is so typical of Spanish waiters. I sat and sipped my wine, watching a couple of children play on the fences nearby—and this is also typical of Spain, where parents take their young kids out to bars at night. In short, everything was perfect. There is something special about Andalusia.

Hey Roy,

Great post man. The puentes here are amazing, and in both contexts.

I live here, have done for 13 years and your blog and information is impressive.

In what ways would you say seville is different from Madrid? Could you imagine living down here?

Will be following your blog from now on. I also write about Spain.

Thanks

Barry

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Barry! Thanks for reading! I suppose the strong Meditteranean culture of Seville is what most sharply distinguishes it from Madrid in my eyes.

Your blog looks cool! I too play guitar, write novels, and teach English. Pleasure to be in contact!

LikeLiked by 1 person

No worries Roy, good to build contacts. What sort of novels have you written? Where can I get a copy? Best of luck.

LikeLike

I wrote a “philosophical” novel that I haven’t done anything with yet…

LikeLike