The plane landed late; and by the time the metro took us to the city, it was midnight. Though the Airbnb was not far from the metro stop, we were so tired that we elected to take a taxi. The driver grimaced when he saw the address.

“How much you pay to stay there?” he asked.

“Not much,” I said truthfully.

“You should pay nothing!”

He dropped us off in front of a long, dark alley.

“Stay on that side,” he told us, before driving off.

“I guess this is it,” I said, and we hesitatingly began to walk into the darkness.

Just as we approached the door, a noise startled us. Two homeless people were crouched right beside the door, talking. In truth I had no reason to think that they posed any kind of threat. But the taxi driver’s words had put me on edge. I fumbled with the lockbox on the door, reading the relevant digits from my phone and tugging. The thing popped open and revealed our keys.

We took the elevator to the top floor. There, I read in the instructions that I was to use the blue key for this one. My friend Becca tried to open it, but to no avail.

“Are you sure it’s this one?” she said.

“Yes, it says the blue key for the blue door.”

She tried again.

“It’s not working,” she said. “Want to try?”

I pocketed my phone and grabbed the key. But as soon as I turned it I felt a snap—the key had broken off in the lock. I was horrified. It was one o’clock in the morning and I had just jammed the lock of our apartment. There was nothing to do but to call the host, who I hoped lived close by. Luckily he picked up quickly.

“You what?” he said.

“The key broke off in the lock.”

He grumbled.

“How hard is it to open a door?” he said.

“I’m sorry…”

“You know ten people are staying there?”

“Yes, I know it’s…”

“Just wait there.”

I assumed that he would have to call the locksmith, which on a Friday night at one in the morning could easily take hours and cost hundreds of euros. But, to my immense relief, within five minutes he appeared carrying a box of tools. The key shard was extracted and, with some more scolding, we were ushered inside. He then opened a lockbox inside the apartment and gave us a replacement key. The charge was five euros.

“Thank you!” I said, marvelling at the efficiency of the process. Guests must break keys in the door all the time, if he had it down to such a science.

Anyways, the ordeal was over: we had arrived in Athens. From the balcony of our Airbnb we could see it: the Parthenon, high up on its hill, gleamingly lit with floodlights. I looked at the ancient temple, relaxed, and felt that strange wondrous feeling of finally seeing something with your eyes which you have seen a thousand times in photographs.

I was finally here, in Athens, the honorary birthplace of Western culture. I was in the city of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle; of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides; of Thucydides and Pericles and Solon. For worshippers of history, no ground is more sacred. And yet my first experience in this city of philosophy and art was being frightened by a taxi driver and then criticized by a disgruntled landlord.

Our first stop was the National Archaeology Museum. As one might expect from an archaeology museum in one of the greatest of ancient cities, this is one of the city’s cultural jewels. It is located right in the heart of Athens, in an impressive neoclassical building that evokes the grandiose history it hopes to document. When we went, the line was short and the price was entirely reasonable.

The collection begins with a set of artifacts which cannot be properly called ‘Greek.’ Some of these are Cycladic art, from the Cyclades, a collection of small, rocky islands off the Greek coast. The art is remarkable, both for its high quality and for its extreme contrast to what we normally think of as ‘Greek’ art. There is no hint of realism in these works. To the contrary, the sculptures of faces and bodies are heavily stylized, leaving a characteristically angular and abstract form which would fit in well in any modern art gallery. One of my favorite works from this section is the representation of a harp player, whose instrument seems to emanate from his leg.

Another civilization which flourished before the ancient Greeks were the Mycenaeans, whose culture covered much of modern-day Greek, the Peloponesus, and the islands. The archaic culture takes its name from the greatest city of its era, Mycenae. One of the artistic masterpieces from this period is the so-called Mask of Agamemnon. This is a funerary mask made of pounded gold around 1500 BCE. The mask owes its name to its discoverer, Heinrich Schilemann, who believed it to belong to the legendary king of the Trojan War. Nowadays this link seems extremely unlikely, if not fanciful. The mask is beautiful, nonetheless. Its highly stylized features evoke an individual—noble, powerful, and tranquil in the repose of death.

What I stumbled upon next astonished me: the Antikythera mechanism. This is one of the most remarkable artefacts in history, one which I had heard about several times from documentaries and television. But I had no idea it was here. The Antikythera mechanism is a highly sophisticated device used to compute the positions of celestial objects and to calculate eclipses. In essence it is an ancient computer. It was discovered in a shipwreck off the coast of Antikythera, in 1901, and was made some time around 100 BCE. Badly corroded by its centuries under the sea, and broken into several fragments, the pale green chunks of metal hardly do justice to the triumph that such an object represents.

In technical sophistication it would be over a thousand years until Europeans created anything comparable. The mechanism contained over 30 gears whose turnings could model the irregular movements of the sun, moon, and planets. It would be wound with a little crank, and it was originally covered with inscriptions of the months and days (Egyptian names written in Greek script) and the intercalandary days used to correct the Egyptian 360-day year. The level of knowledge needed to create such a device is extraordinary. Merely developing the mathematics needed to accurately calculate the moon’s orbit, for example, took generations of work. And to be able to build such a delicate device that embodies these mathematical relationships in a usable form—that is true sophistication.

Near the fragments of the original device are several modern reconstructions of what it may have looked like. All of these agree that it was a medium-sized box with a metallic face that displayed several rotating rings. The device is not exactly beautiful to look at; but in what it means for our species—the ability to chart and predict the movement of celestial bodies with mathematical precision—it is an artifact more moving than even the finest sculpture.

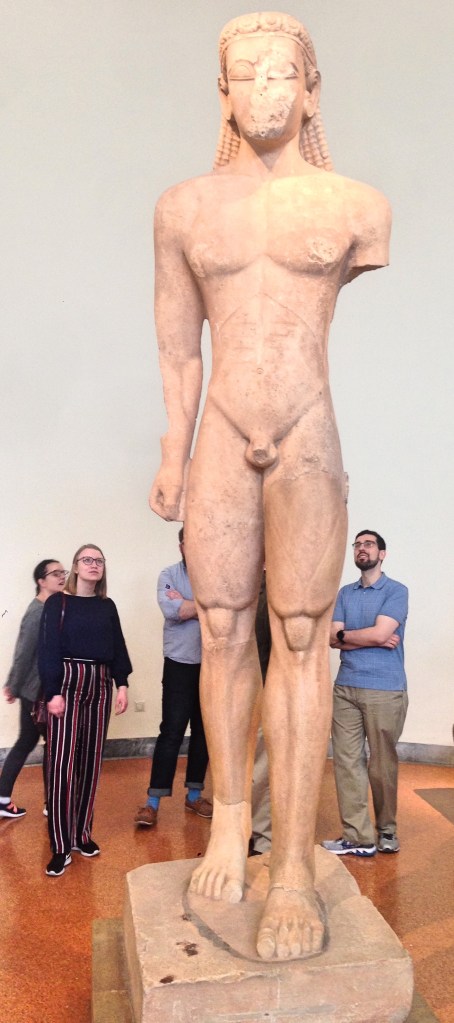

The museum’s sculpture collection allows the visitor to see the evolution of Greek technique. The archaic period was characterized by a notable influence of Egyptian art upon the Greeks. One can see this clearly in the Knoisos Kouros, a large statue of a young man made around 500 BCE to mark a grave. The figure is stiff, with his arms straight at his sides; his hair is braided behind him; and his mouth wears that characteristic ‘archaic smile,’ a sort of otherworldly grin typical of this period. Nearby is a statue of a sphinx—with a smiling human head, an eagle’s wings, and a lion’s body. Clearly these early Greeks were admirers of their ancient counterparts in the Nile Valley.

Compare this statue with one made about 100 years later: the Poseidon of Cape Artemision. This is a bronze statue depicting a bearded god, his arm raised in a gesture of smiting, found in a shipwreck. (It is unclear whether it is Poseidon or Zeus, since the object in the god’s arm—a trident or a thunderbolt—has been lost.) Here the body is far from stiff, but poised to strike, its right foot lifting up in preparation. The face, too, is far more expressive. Gone is the archaic smile. The bearded god is magnificent, foreboding, and regal.

Found in that same shipwreck is the Jockey of Artemision, a bronze statue that was made even later, at around 150 BCE. Here realism has advanced considerably. We see a young boy riding a horse. The horse is frozen mid-stride, while the impossibly small boy is seated bareback. To my eyes the work has a decidedly morbid air: the horse looks sickly while the boy looks frightened. But it is a masterful work of art, with every muscle of the horse’s body modeled beautifully, and its face wonderfully lifelike. Again, we must marvel at the technical sophistication needed to create such a well-balanced, realistic sculpture out of bronze.

The Golden Age of Greek art is, however, normally considered to lie between the stiffness of the archaic period and the realism of the Hellenistic period. During this properly classical age, idealized form met technical sophistication, creating those wonderful heroic figures who are both believable and yet beyond human. Among these we might class the Aphrodite of Knidos or the Capitoline Venus, iconic statues of the idealized female body, both of which can be found at the museum—or, at least, Roman-era copies.

One of the museum’s great male nudes is the Antikythera Ephebe, a bronze statue found in the same shipwreck that yielded up the above-mentioned mechanism. As with the case of the Poseidon statue mentioned above, the identity of the young man is unclear, since we do not know what he held in his hand. Nevertheless it is an extraordinary representation of the perfect human form—very far-removed in conception and execution from the Egyptian-influenced statues created just two centuries before.

The museum has many masterpieces; but one cannot do justice to its collection by focusing on these pieces alone. There are superb examples of ancient coins and pottery, and sculptures ranging from 1,000 BCE to the Roman era. The Greek vase-painting alone deserves and rewards close study. But, for me, the most moving galleries were those which contained ancient funerary markers. These are like tombstones, most often decorated with statues in high relief, that show us intimate and often touching representations of the departed. In one we see a father holding a baby, whose little hand is outstretched towards his deceased mother. It is wonderful art; but, more importantly, it is so wonderfully human.

This was our first morning. As visiting museums is tough work, we emerged tired and hungry. But the weather was lovely beyond belief. It was mid-March, and Madrid was still feeling the winter chill. Athens, meanwhile, was sunny and perfectly warm, and the sky had nary a cloud. We were also fortunate when it came to food. Greek food is justly famous; and Athens, of course, has no shortage of it. We ate lunch in a place called O Kostas, ordering two lamb gyros and fries with feta cheese. It was delicious. For dessert, we headed to a spot called Lukumades, which serves a type of pastry called, appropriately, Loukoumades. These are essentially like doughnut holes—fried balls of dough—but they are especially sumptuous, soft on the inside and slightly tough on the outside. Traditionally they are served with honey, which is what I ordered. It was a voluptuary experience.

After we ate, we headed to a tour that Becca had booked before we arrived. We wanted to see at least some of the country outside of Athens. A trip to Delphi or, better still, one of the Greek islands would have been ideal; but since we had limited time, we settled on a short trip to the Temple of Poseidon. The tour met at a hotel, where we boarded a large tour bus. I was rather impressed at the driver’s ability to maneuver the blimp-like vehicle through the narrow Athenian streets. Our guide gave us a running narration of the sites we were passing, through the bus’s PA system, as well as giving us some background as to the history and the mythology associated with the temple.

Apart from its major monuments, the city of Athens is itself not especially attractive—a clutter of unremarkably buildings—but the landscape surrounding the city partakes in all that fabled beauty of the Greek countryside. The bright blue Mediterranean, the gentle hills and small islands sparsely covered with green, and the little towns nestled among these elevations—the whole scene brought my thoughts back to the country’s ancient past.

Many times I have heard it said that the particular geography of Greece was the key to its cultural development: that the hills and mountains made overland travel difficult, while the many islands and harbors made sea travel, and thus international trade, far more profitable. Thus, the Greeks became excellent sailors and developed independent city-states, whose merchants sailed far and wide, coming into contact with other cultures and bringing back ideas, arts, and technologies from afar. I have even heard it said that the particular clarity of the Meditteranean sun in Greece shaped their logical philosophy and their classical art. Theories such as these should always be handled with caution. Still, as I looked at this dramatic and yet harmonious landscape, I could not help but feel inspired myself.

Finally we reached the temple. It stands on a bluff overlooking the sea, a commanding position for the house of a god. The guide led us from the parking lot to the site, gave us a little speech, and then let us roam free. Built during the Golden Age of Athens, under Pericles (c. 440 BCE), the temple itself is now in a ruined state, with less than half of the original columns standing and nothing of the roof or internal structures to speak of. Even so, the temple has been a tourist destination for many years, as attested by the many graffiti carved into the rock, including the name of Lord Byron. The ruined temple is perhaps all the more charming to modern visitors because of its ruin. As it stands now, the columns open up towards the viewer, and the temple itself becomes a kind of lens or frame for the landscape around it.

Martin Heidegger, the philosopher who idolized the Greeks, was horrified by most of what he actually saw on his trip to Greece. This temple was one of the few sites that inspired him, which he recorded in his influential essays on aesthetics:

Standing there, the building rests on the rocky ground. This resting of the work draws up out of the rock the obscurity of that rock’s bulky yet spontaneous support. Standing there, the building holds its ground against the storm raging above it and so first makes the storm itself manifest in its violence. The luster and gleam of the stone, though itself apparently glowing only by the grace of the sun, first brings to radiance the light of the day, the breadth of the sky, the darkness of the night.

My response to the structure was, however, muted compared with my response to the landscape surrounding the temple. Nevertheless, it was special to see my first true Ancient Greek temple, in situ. It is a work of art that perfectly complements nature.

We arrived back around dinnertime, ate, and then went to bed. Tomorrow was going to be a big day.

We awoke in our pitch-dark room early. It was time to visit the Acropolis. Breakfast was easy. The streets were full of vendors selling sesame bread rings—which taste like thin, crunchy bagels.

The walk to the base of the hill was short, and it was not long before we began to encounter ruins. First was Hadrian’s Library, built during the reign of that Roman Emperor to house some of the cultural treasures of Athens. (Educated Romans were acutely aware of the cultural debt they owed to Greece.) Little of this structure remains, just a few walls and free-standing columns in a grassy field. Nearby is the Roman agora (an agora is an open space used for assemblies). Athens’ original agora was apparently swallowed up by surrounding buildings, making a new one necessary during the Roman era. The most famous structure in this area is the Tower of the Winds, possibly the first weather station in history, equipped with a wind vane, multiple sundials, and a water clock.

Our path then took us past the iconic Theater of Dionysus. Built into the side of the hill, the theater will be familiar to anyone who has seen later Roman theaters, partially because the Romans refurbished it, and partially because this is the prototype of all theaters that came later—possibly history’s first theater. Semicircular rows of seats descend to the stage, which is framed by a grandiose stone backdrop. It was amazing to see the venue where, in all probability, the works of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes were performed. It may be difficult for us to appreciate this nowadays, when theater and all its offspring (television, movies) so dominate our entertainment and art. But at one point theater was an entirely new, cutting-edge artistic medium. The Greeks not only gave birth to this artform, but quickly produced masterpieces, still powerful after more than 2,000 years.

The path took us on a gradual ascent up the hill of the Acropolis. Soon we came to the entrance to the site. Though there were lots of tourists mulling about, I was surprised that we did not have to wait on a long line to get inside. It was not at all like visiting the Colosseum in Rome: we paid and walked right inside. A little more walking, and we were standing before the ancient entrance to the Acropolis, the Propylaea. This consists of a marble colonnade, with wings on either side, which sits grandly atop the stairs leading up to the Acropolis. At the time this was a sacred space, and so the Propylaea served as a gate, and was used to control access to the city’s temples, barring the way of any undesirables.

We climbed the stairs, passed under the Propylaea—and there it was, the Parthenon.

Seeing any iconic site evokes a peculiar feeling: a quick succession of awe, disappointment, boredom, excitement, curiosity, wonder, and awe again. First you think, “That’s it!” Then you think, “Well, I guess that’s it.” And then you start to really look at it, in a way you never could in photos or in videos. Now you can sense the building’s proportions, and see it in the proper situation—the strong Mediteranean sun bearing down, the bear rock of the hill underfoot, and the expansive view on every side.

The Parthenon was built at the height of Athenian power, at around 450 BCE. Athens had just emerged victorious from a war with Persia, the very war recorded by Herodotus in his Histories. During that conflict, the Persians had ransacked the city of Athens and had burned several sacred sites, including an older temple. Nevertheless, Athens emerged from the war stronger than ever before, the de facto leader of the Delian League—a loose federation of Greek city-states. Indeed, the league dues paid to Athens by the other members helped to fund the new temple, something that the other cities did not appreciate. The high-handed leadership of Athens eventually resulted in the Peloponnesian War, recorded by Thucydides, which ended with the defeat of Athens by Sparta and its allies, and the end of the Athenian Golden Age.

The construction of the Parthenon, then, coincides exactly with Athens’ most glorious moment. On the surface the building is simplicity itself: rows of columns (69 in all, originally) holding up a roof. But the beauties are in the subtleties. First, the columns themselves swell slightly in the middle, in order to counteract the optical illusion that perfectly straight columns are narrower in the middle. The whole foundation itself is slightly bowed, or bent, which helped rain flow off the roof as well as made the building stronger—not to mention lessening the stiffness of the building’s profile.

Then there is the artwork. Very little of the original sculptures remain, much of it having been carted off to England by Thomas Bruce, the Earl of Elgin (more on that later). As extraordinary as much of this artwork is, it was not meant to be the main focus on the structure. In fact, it was placed so high above that it is unclear how it could have been properly seen. The Ancient Greek traveller, Pausanias, does not even mention the friezes that are now considered touchstones in the history of art. Instead, the main focus of the building was an enormous statue of Athena, holding the winged form of Nike (or vistory), now lost to time.

We do have a good idea of what this statue would have looked like, though, from several reproductions and representations, as well as from written descriptions. Ironically, as the classicist Mary Beard points out, we in the present would likely not have found this statue particularly beautiful. Certainly the full-scale reproduction in Nashville is not inspiring. The gargantuan figure was not meant to be a work of art, after all, but a cult image—indeed, the goddess herself made incarnate. And the temple was not a place of services or worship, such as a church or a mosque, but a place to house the offerings to this physical goddess.

Nowadays, we are not apt to see the ruined temple as the house of a goddess, or even as primarily a religious structure. Rather, we cannot help seeing the Parthenon as a kind of visual representation of the culture that gave us philosophy, art, and democracy. We see the ancient structure, and we think of Pericles, the great leader of Athens, and his iconic funeral oration:

If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences…if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition. The freedom we enjoy in our government extends also to our ordinary life. There, far from exercising a jealous surveillance over each other, we do not feel called upon to be angry with our neighbour for doing what he likes…

But the Parthenon has been affected by far more history than merely Classical Athens. The building served as a church for much longer than it ever was the home of Athena. The pagan temple was first consecrated under the Byzantines as a Greek Orthodox church; and then, during the crusades, the Parthenon fell under the control of several different Western European states, becoming a Roman Catholic church controlled by the French, the Italians, and the Catalans in turn. Finally the Ottoman Turks seized control, and the Parthenon became a mosque. In 1687, during a war with Venice, the Ottomans unwisely decided to use the Parthenon as a refuge for civilians, as well as a storage depot for gunpowder. A stray Venetian shell ignited the powder, killing dozens and seriously damaging the building’s structure.

Thus, what we see now is merely a shadow of what the building would have originally looked like. In fact, the Parthenon has already been partially reconstructed; at the beginning of the previous century, not even the building’s outline remained standing. Even so, what would have been the dark internal chamber is now nothing but empty space (where a large crane was parked when I visited). What stands, in other words, is only the outer rim of the building—as if a house had been gutted, leaving only its external walls. What is more, almost all of the sculpture has been destroyed or removed; and, importantly, the bright paint that would have originally decorated the Parthenon has long ago been washed away.

The building we celebrate, then, is very different from what the Athenians actually built. And as in the case of the Temple of Poseidon, I suspect that we cherish the Parthenon because the passing years have turned it into a noble ruin. Rather than a colorful exterior containing a dark internal chamber, we now find a skeleton made of pure white marble, filled with nothing but sunlight and air. What we see, in other words, is only the mathematically clean and elegant outline of the original structure—giving us a rather false idea of what life in Ancient Greek was actually like.

Still, it is beguiling to behold. The temple has a mesmerizing power, its irregularities so subtle as to be unnoticeable and yet intriguing. What could have been a stiff and rather lifeless building instead appears supple, graceful, and dynamic.

It is worth momentarily pulling your gaze from the Parthenon to examine some of the other temples on the Acropolis. The most notable of these is the Erechtheion, a somewhat smaller temple dedicated to both Poseidon and Athena. According to the founding myth of the city, those two gods had a contest in order to which one of them would become the city’s patron deity. Poseidon struck the ground with his trident, and caused a well to gush forth. Unfortunately, however, it the water was salty. Athena responded by causing an olive tree to grow. As olives are fundamental to the Mediterranean diet, the Greeks wisely chose Athena. This temple marks the spot where the contest supposedly took place, and was built around the two miraculous gifts—the marks of Poseidon’s trident and the sacred olive tree.

The profile of the Erechtheion is somewhat odd, since it was perforce built over uneven ground, to which the architects had to adapt. Its most famous feature is the Porch of the Maidens, a porch held up by the statues of six young women, called Caryatids. Now the statues in the porch are all replicas. One of them was carted off by the infamous Lord Elgin, and now stands in the British Museum. The other five have been moved to the Parthenon Museum (more later).

The last temple on the hill is the Temple of Athena Nike. It is a small temple situated near the entrance, which was decorated with friezes of the highest quality, some of which are now in the British Museum, and others which have remained in Athens. Besides these other structures, it is worth mentioning the view from the hill of the Acropolis. Athens spreads out in all directions, an endless sea of mostly white buildings hemmed in by distant green mountains. From here I could see the Temple of Hephaestus, a remarkably well-preserved temple that does not receive a fraction of the attention from tourists as do the ruined temples in the city—which supports my earlier point, that we are attracted to these buildings precisely because they are ruins. Near the temple is the Church of the Holy Apostles, a 10th century Orthodox Church.

I could also see the famous Areopagus, a rocky outcropping said to be where the gods held Ares on trial (thus the name), and, according to Aeschylus, where the gods held Orestes on trial for the murder of his mother. The ancient Athenians used this hill for their own trials, and St. Paul was said to have made a speech to the Athenians in this spot. John Milton referenced this classical past in the title of his iconic defense of a free press, the Areopagitica. Looking in another direction I saw the ruins of the Temple of Olympian Zeus, at one time the largest temple in Greece, but now only a collection of free-standing columns in a grassy field. Most striking of all was Mount Lycabettus, a hill whose rocky peak is taller even than the Acropolis.

I descended from the Acropolis feeling a mixture of triumph and deflation. The big moment was over: I had seen the Parthenon. Was I any the better for it? But we still had a great deal more to see, much of it found in the Acropolis Museum, located right down the hill from the Acropolis itself.

The Acropolis Museum is the second great museum in the city of Athens. Compared with the Archaeology Museum, this one is a much younger institution, having been opened in 2009 after many false starts. The museum, thus, projects a sleek, modern aspect to the visitor. Even the building itself is interesting and innovative. Designed by the Swiss, Parisian, New Yorker Bernard Tschumi, the entire structure is lifted above an ancient archaeological site, leaving the ruins below both visible to visitors and accessible to researchers.

Unfortunately, photos were not allowed in most of the museum, so I must rely on my hazy memory. The first exhibit was housed in a large hall. Shards of broken pottery and other small archaeological remains were housed in glass cases along the walls, while free-standing statues and structures were scattered throughout the space. This is the gallery containing artifacts from the slopes of the Acropolis—consisting of a mishmash of domestic items and the remains of various small sanctuaries. The floor has several glass panels, allowing the visitor to look down at the ancient site below (called the “Makrygianni plot”). As the museum’s website explains, the upwards slope of this hall intentionally recalls the slope of the Acropolis hill itself: quite a nice touch.

After climbing some stairs, the visitor then finds herself in a sort of enormous warehouse, with concrete grey pillars holding up the high ceiling, and large windows letting in the bright Greek sun. The space is full of statues and fragments of buildings, many of them visibly archaic. These are the remains of the pre-Golden Age Acropolis, the temple complex which was largely destroyed by the invading Persians. Only broken fragments of the decorations remain, but they are beautifully suggestive. Particularly noteworthy are the pediments from the Hekatompedon, the so-called Ur-Parthenon that stood on the site of the current temple. We see a lion killing a calf, the curling body of a snake, and a man with three bodies (each of them wearing the above-mentioned archaic smile). For me, the statues of the animals are especially lovely. The Golden-Age Greeks seldom depicted animals in their visual art, preferring to focus instead on ideal human form.

Moving on through this floor, the visitor then comes to a special balcony, where she will find five familiar friends: the Caryatids who hold up the Porch of the Maidens in the Erechtheion. They are exhibited, appropriately, on a balcony within the museum. These are the originals—at least, those that have remained in Athens. Besides taking one back to England, Lord Elgin badly damaged another of the Caryatids in his attempt to remove the sculpture. The authories in the museum have done their best to piece her back together again, but the difference is stark. The mythological significance of these Caryatids is, as it happens, uncertain. According to the museum’s website, the most plausible theory is that they represent choephoroi (mourners, or “libation bearers”) of Cecrops I, the king of Athens who was supposedly buried there.

taken from Wikimedia commons

Nearby are the friezes taken from the Temple of Athena Nike. Among these is a justly famous sculpture of a goddess adjusting her sandal. For me, it is a wonderful piece. The way that the thin cloak drapes over the goddess’s body is masterful, both revealing the countours of her body and creating a fascinating geometrical pattern. Indeed, the lightness and daintiness of this image reminds me of nothing else so much as Degas’ many paintings of ballerinas.

So far, we have already had much to see: but the museum’s main raison d’être is still unmentioned. On the top floor is a space especially constructed to house the friezes and sculptures from the Parthenon. It is an enormous space, flooded with light, made to be the exact same dimensions of the original building, and even oriented the same way. In the original building, the friezes would have been far above the visitor, with most of their beautiful details impossible to see. Here, the friezes are dispalyed above the viewer, but close enough for pleasurable viewing. At either end are the remains of the pediments—fragmentary sculptures of gods and heroes.

In my opinion, it is a brilliant design, doing justice to the original setting of the works while allowing for added visibility. The Greek authorities had good reason for investing in such a cutting-edge design, you see. Remember that the vast majority of the original friezes are not in Greece at all, but in Athens, thanks to the aforementioned Lord Elgin. The Louvre has some other pieces, and a few other fragments are scattered here and there. As one might expect, Greece has been trying to get back these originals for decades, arguing that they were taken under improper settings. One of the main arguments against returning the works was that they are impossible to see in the original setting. But the construction of this gallery had made that argument a moot point. Now, Athens has arguably a better space for displaying the artwork than London or Paris.

The British Museum and its counterparts have, unsurprisingly, been less than forthcoming in these demands to return the originals. For one, losing the Parthenon freize would mean losing one of the British Museum’s prized posessions. What is more, giving back the artwork would set a precedent that could potentially unravel the British Museum completely, considering how many of the British Museum’s prized works have been taken from other parts of the world, often under less than scrictly legal circumstances. Greece is just one of many countries demanding repatriation.

For my part, I would be deeply sad to see the British Museum come apart. But after seeing the frankly amazing gallery in Athens, I cannot help but think that this is where the Parthenon freize belongs—lit up by the Mediterranean sun, with the Parthenon itself visible through the wide windows. Seen here, amid so much other classical art, the work is just more meaningful than in foggy London.

So what is in the gallery, if the originals are in London and Paris? Well, mostly plaster casts. Certainly they lack the quality and luster of the original marble, but it is better than the proverbial nothing.

The sculptures and friezes of the Parthenon are virtually the definition of classical perfection for us moderns. In the pediments (under the slanted roof) we see the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus on one end, and the competition between Athena and Poseidon for the loyalty of the citizens on the other—though these are so badly damaged that only fragments of heads and bodies remain. Somewhat better preserved are the metopes. These are panels of friezes in high relief that went around the outside of the building. There were, originally, 92 of these; but time, deliberate destruction (by Christians who thought them graven images), and accidental tragedies (such as the powder explosion) have destroyed most of them beyond recognition. The best ones are mostly in the British Museum, while some of the most ruined panels are still in place on the building, all by invisible to the visitor.

The metopes were divided into four themes, one per side: the gigantomachy (the fight between the gods and the giants); the Amazonomachy (the fight between Greeks and Amazon warriors); the fall of Troy; and the fight between the Lapiths and the centaurs. The theme is clear: war. Each of the panels depicts two figures, embroiled in conflict. These four mythical wars encapsulate the worldview of Periclean Athens quite well: the supriority of the divine over earthly force, the superiority of men over women (and the Athenians were patriarchal even by ancient standards), the superiority of Greeks over non-Greeks (xenophobia is nothing new), and the superiority of humans over the beasts. It is easy to see these articles of faith as a response to the Persian invasion—an assertion of the superiority of Greece over everyone else.

As works of art, the panels of the fight between the Lapiths (legendary Greeks) and the centaurs are perhaps the finest from the Parthenon. Some of them must certainly be ranked among the finest sculptures in Western history. However, as Mary Beard points out in her guide, several of these panels are manifestly inferior—stiff, awkward, misproportioned. It seems that the Greeks hired mediocre workmen in order to get the building finished. After all, the entire building was finished in less than ten years. Compare that to the decades, and even centuries, it took to build the great cathedrals!

The last major sculptural work is the frieze, which went around the naos in a continuous panel. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon consisted of two major parts: the peristyle, which are the columns that wrap around the perimeter, and the naos, or inner chamber. The Parthenon as we know it today consists exclusively of the peristyle, which contained the pediments and the metopes. As a result, imagining how the frieze would have originally looked is somewhat more difficult for us.

The frieze, sculpted in rather low relief, depicts an enormous procession, with men, women, and children, animals of various sorts, and people on horseback, bearing all sorts of goods and objects. It is an amazing work of art, containing immense variety within a coherent narrative structure, in a style that has come to be synonymous with Classical Athens. Ironically, however, scholars are still unsure what this iconic work of art is supposed to represent. The work is virtually unique for being a representation of daily life—something otherwise absent in Greek artwork. Most would accept that it is some sort of religious procession, but which one is yet to be determined. The museum’s website asserts that it is the Panathenaia—the most important ritual in honor of Athena—but, according to Mary Beard, this is far from clear. So, as it happens, we do not know what one of the most influential works of Western art is about.

After our busy morning on the Acropolis and several hours in the museum, we had ingested all of the art and architecture we would digest for one day. Our next stop was quite a bit different. Becca wanted to visit a famous sandal shop, which used to be owned and run by Stavros Melissinos, known as the poet sandalmaker. The shop is well-known; and it counts many celebrities as past customers, including John Lennon (after whom there is now a sandal named). Now, I must admit that I am not an expert sandal connoisseure. I have been wearing Birkenstocks for most of my life, and they suit me just fine. But other people seem pretty pleased with the shop’s products.

We spent the rest of our time just wandering and eating. Virtually everything we tasted was excellent. Before long, it was time to brave the dark alley once more, and go to sleep in our little bunk-beds. The next morning we walked over to Syntagma square—the central plaza of Athens—and then took the metro back to the airport. It had been quite a journey. Surely, we had missed a great deal of what Athens has to offer. But what we had seen was enough to make Athens one of my favorite trips in Europe. I will return one day.