Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

In any case, truly democratic debate cannot proceed without reliable statistics.

For such a hefty book, so full of charts and case studies, the contents of Capital in the Twenty-First Century can be summarized with surprising brevity. Here it goes:

For as long as we have reliable records, market economies have produced huge disparities in income and wealth. The simple reason for this is that private wealth has consistently grown several times faster than the economy; furthermore, the bigger your fortune, the faster it grows. As a result, in the 18th and 19th centuries, inequality was high and consistently grew: most of the population owned nothing or close to nothing, and a small propertied class accumulated vast generational wealth. This trend was only reversed by the cataclysms of the 20th century—the World Wars and Great Depression—as well as the resultant government policies, such as social security and progressive taxes. But all signs indicate that the general pattern is re-emerging, and we are reverting to levels of inequality not seen since the Belle Epoque.

This is a relatively simple story, but Piketty goes to great lengths to prove it. Indeed, the value of this book consists in its wealth of data rather than any seismic theoretical insights. Piketty is an artist on graph paper; and with a few simple dots and lines he cuts to the heart of the matter. The large time scales help us to see things invisible in the present moment. For example, while some economists have thought that the ratio of income going to labor and capital was quite stable, Piketty shows that it fluctuates through time and space. Seen in this way, the economy ceases to be a static entity following fixed rules, but something all too human—responding to government policy, cultural developments, and historical accidents.

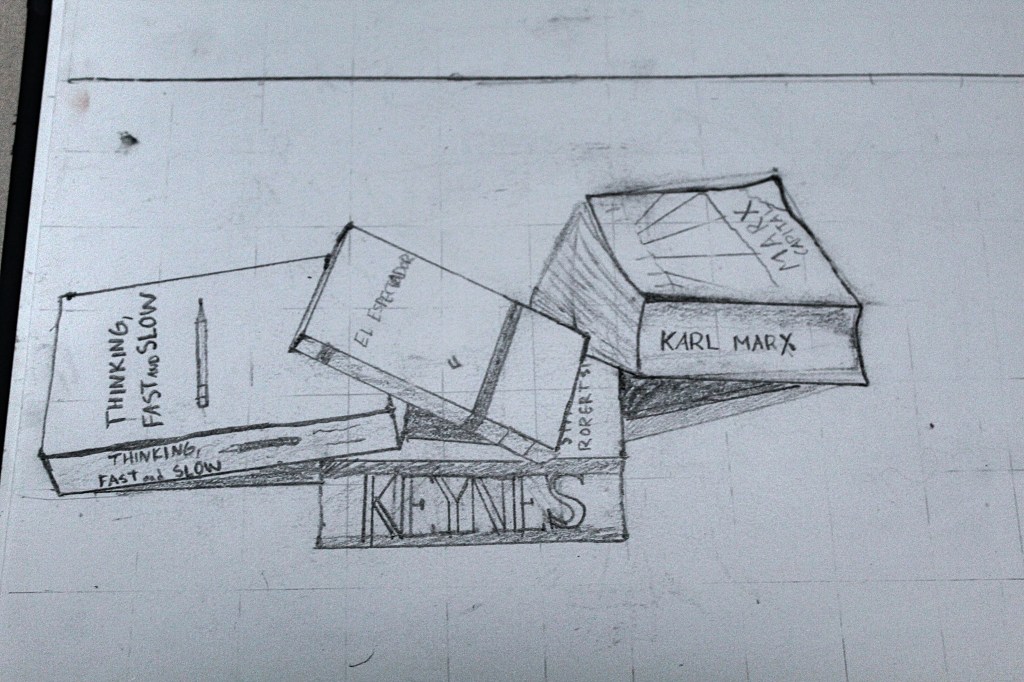

Given the title of this book, comparisons to Marx are inevitable. Piketty himself begins with a short historical overview of the thinkers he considers his predecessors, with Marx given due credit. Piketty even concurs with the basic Marxian logic—that capitalism inevitably leads to a crisis of accumulation, with the capitalists siphoning off more and more resources until none are left for the rest of the population (with revolution inevitable). If we have avoided such a crisis, says Piketty, it is because Marx based his analysis on a static economy, not a growing one. The twentieth century was exceptional, not only because of its many calamities, but also because it saw enormous rates of economic growth, which also helped to offset the basic logic of capitalist accumulation. Growth rates have significantly slowed in this century.

In summarizing Piketty this way, I fear that I am not doing justice to his appeal. This book is at its most enjoyable when Piketty is at his most empirical—when he is taking the reader through historical trends and case studies. This is extremely refreshing in an economist. I often complain that economics, as a discipline, is needlessly theoretical, getting lost in abstruse debates about how certain variables affect one another, rather than focusing on observable data. Piketty explicitly rejects this style of economics, and puts forward his own method of historical research. This has many advantages. For one, it makes the book far easier to understand, since Piketty’s point is always grounded in a set of facts. What is more, this way of doing economics can be integrated with other disciplines, like history or sociology, rather than existing apart in its own theoretical realm. For example, Piketty often has occasion to bring up the novels of Jane Austen and Honoré de Balzac to illustrate his points.

Well, if Piketty is even approximately correct, then we are left in a rather uncomfortable situation. As Piketty repeatedly notes, vast inequality leads to political instability and the undermining of democratic government, as the super-wealthy are able to accumulate ever-larger influence. So what should we do about it? Here, the difference in temperament between Marx and Piketty is especially apparent. Instead of advocating for any kind of revolution, Piketty puts forward the decidedly wonkish solution of a global tax on wealth. The proposed tax would be progressive (only significantly taxing large fortunes) and would extend throughout the world, so that the rich could not simply hide their money in tax havens. Yet as Piketty himself notes, this solution is nearly as utopian as the Proletariat Revolution, so I am not sure where that leaves us.

As much as I enjoyed and appreciated this book, nowadays it is somewhat difficult to see why it became so wildly popular and influential. This had more to do with the historical moment in which it was published than the book itself, I suspect. The world was still reeling from the shock of the 2008 crash, and the public was just coming to grips with the scale and ramifications of inequality. Specifically, while most people tend to think of inequality in terms of income—partly, because most people do not have much wealth to speak of—Piketty’s emphasis on wealth, specifically generational wealth, added another dimension to the debate. Piketty evidently succeeded in getting his message across, since I did not find anything in this book shocking. Now we all know about inequality.

While I am no economist, it does seem clear to me that Piketty’s argument has several weak points. For one, his narrow focus on income and wealth distributions lead him to ignore other important factors—most notably, for me, unemployment rates. Further, the major inequality that Piketty identifies—that wealth grows faster than the economy, or r > g—could have used more theoretical elaboration. I wonder: How can private wealth grow so much faster than the economy, if it is a major component of the economy? At one point, Piketty argues that the super rich can afford to hire the best investors and financial consultants; but from what I understand, professional investors do not, on the whole, outperform index funds (which grow along with the economy). Clearly, there is much for professional economists to argue about here.

Whatever its flaws, Capital in the Twenty-First Century is an ambitious and compelling book that made a lasting and valuable contribution to political debate. Piketty may be no Marx; but for a man who loves charts and graphs, he is oddly compelling.

View all my reviews