Federico García Lorca is the most famous playwright and poet that Spain produced in the previous century. This is largely owing to undeniable brilliance, as any readers of Bodas de Sangre or Yerma can attest to. Yet his fame is also due, in part, to the tragic story of his death—executed by Nationalist forces during the first few months of the Spanish Civil War. Among the hundreds of thousands dead from that conflict, Lorca remains its most famous victim. And in death, he has become a kind of secular saint to artistic freedom.

The precise details of Lorca’s murder were, for a long while, rather obscure; and it is largely thanks to the Irish writer, Ian Gibson, that it was finally uncovered. Prior to our trip to Granada, Rebe had read Gibson’s book, El asesinato de García Lorca, and so we had a full Lorca itinerary planned.

Our first stop was the Huerta de San Vicente. This was the summer house of the García Lorca family for the last ten years of the poet’s life. It is a kind of rustic villa, typical of Andalusia, with large windows and whitewashed walls—ideal for keeping cool. We joined a tour and were shown around the house, which has a piano that Lorca would play on (he was a gifted musician, and friends with Manuel de Falla), as well as a desk at which he wrote.

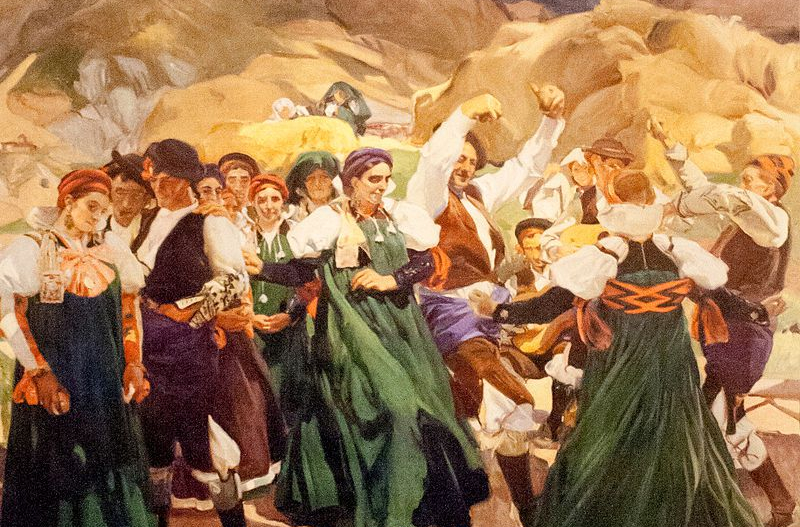

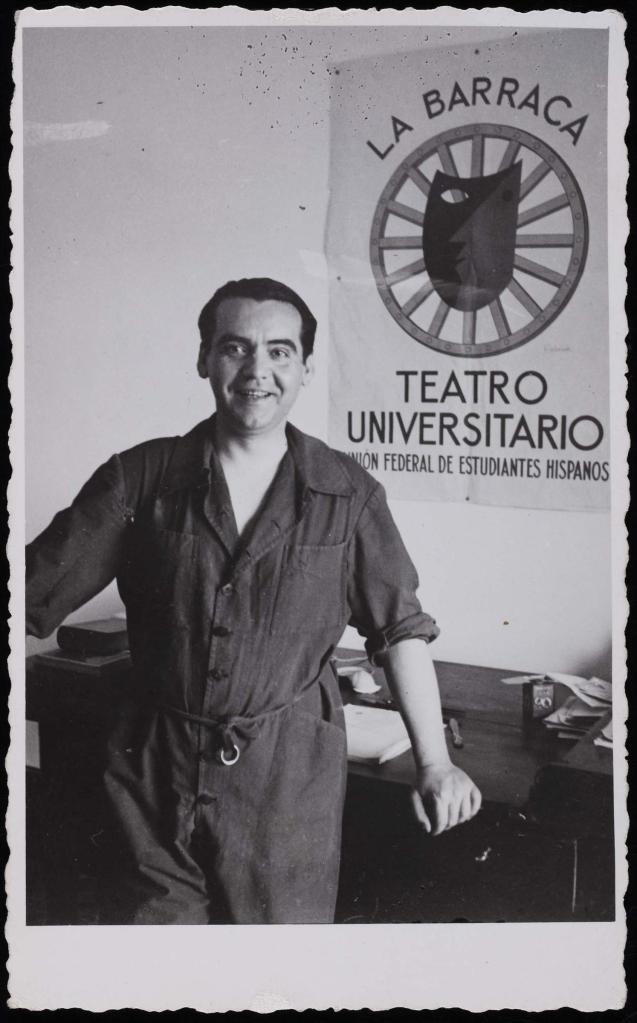

The hour-long visit gave a satisfying overview of the many facets of his short life. Lorca came across as a man wholly devoted to the arts—to music, to poetry, and above all to theater. One of my favorite items on display was a poster for La Barraca, a popular theater group that he helped to direct. They would travel around the countryside and perform for the benefit of the public, putting on avante-garde shows for the masses. It reminds me somewhat of the Federal Theater Project of the American New Deal, and demonstrates that Lorca, while not overtly political, did not shy away from social causes.

Our next stop was the small town of Fuente Vaqueros, which is a short drive from Granada. There, we visited the house where Lorca was born and spent his earliest years. It is a large house with thick walls, ideal for keeping out the heat. We were given a tour—just the two of us—by a local whose grandfather had gone to the same primary school as Lorca himself! He explained that the Lorca family was quite wealthy, having made their fortune in the tobacco business. Indeed, their house was one of the first to receive electricity in the area.

The upstairs of the house was made into a small exhibition space. Among other things, there is the only extant video clip of the poet, as he emerges from a truck used to haul theater supplies. The video has no sound and it lasts for only a few moments. Yet it is a tantalizing glimpse into the past. Also on display are puppets that Lorca made, in order to put on shows for his baby sister.

A short drive from Fuente Vaqueros is the town of Valderrubio, previously known as “Asquerosa” (“Disgusting”). Apparently, this name is a linguistic coincidence, having come from the Latin Aqua Rosae (“Pink Water”), but it led to the unfortunate toponym “asquerosos” for the denizens of this perfectly inoffensive town. Here is yet another house museum of the playwright, this one larger and grander than the one in Fuente Vaqueros. Unfortunately, however, we arrived too late for the tour of this house, and had to content ourselves with a quick walk-through.

But we were on time for the tour of the House of Bernarda Alba. This is an attractive villa next to the Lorca property, where a widow lived with her daughters. Federico used this family as the basis for one of his best plays, La casa de Bernarda Alba, which is about a tyrannical widow who imposes a decade’s long period of mourning on herself and her daughters after the death of her husband. Apparently, the actual family—who I presume weren’t nearly as monstrous as Lorca portrayed them—were understandably quite offended by this, and cut off contact with the Lorcas. And now, to add insult to injury, their home stands as a museum to the poet’s honor!

Our last stop was rather more somber. On the 19th of August, 1936, Lorca was arrested, taken outside the city, and shot. Against the advice of his friends, on the eve of the Civil War he had traveled to his native city. But as war broke out and violence spread, he realized that he was unsafe and so hid himself in the home of family friends, who were members of the right-wing Falangist party. The political connection didn’t help. Along with three other men, he was taken to a spot on the highway between Vïznar and Alfacar and shot.

The place where Lorca was executed is hardly recognizable today. At the time it was a barren hillside, completely devoid of vegetation. Today, however, it is a grove of tall pine trees that cover the ground with shade. We parked the car and walked up a hill, not sure what we were looking for. Then we noticed papers tacked onto trees, like ‘Lost Cat’ posters on telephone polls. They were photos of the people believed to be executed here. There were dozens of these photos, each one with a name, profession, and believed date of death.

Even more unsettling were the white tents, standing empty and silent. They were covering excavation pits, where investigators are finally unearthing the remains of the hundreds of victims executed here, nearly a century after the Civil War. The investigators are also collecting DNA samples from surviving family members, so as to be able to identify any remains they uncover. Lorca’s body is believed to be here somewhere, though it hasn’t been identified yet. (You can learn more about the effort by following the groups’s Instagram.)

To state the obvious, it is chilling to think that such a harmless man—a gift to the world and an ornament to his country—could be deemed so threatening that he had to be executed this way. His last moments must have been terrifying. His work, however, has outlived Franco and his regime, and perhaps it will outlive the current constitution.

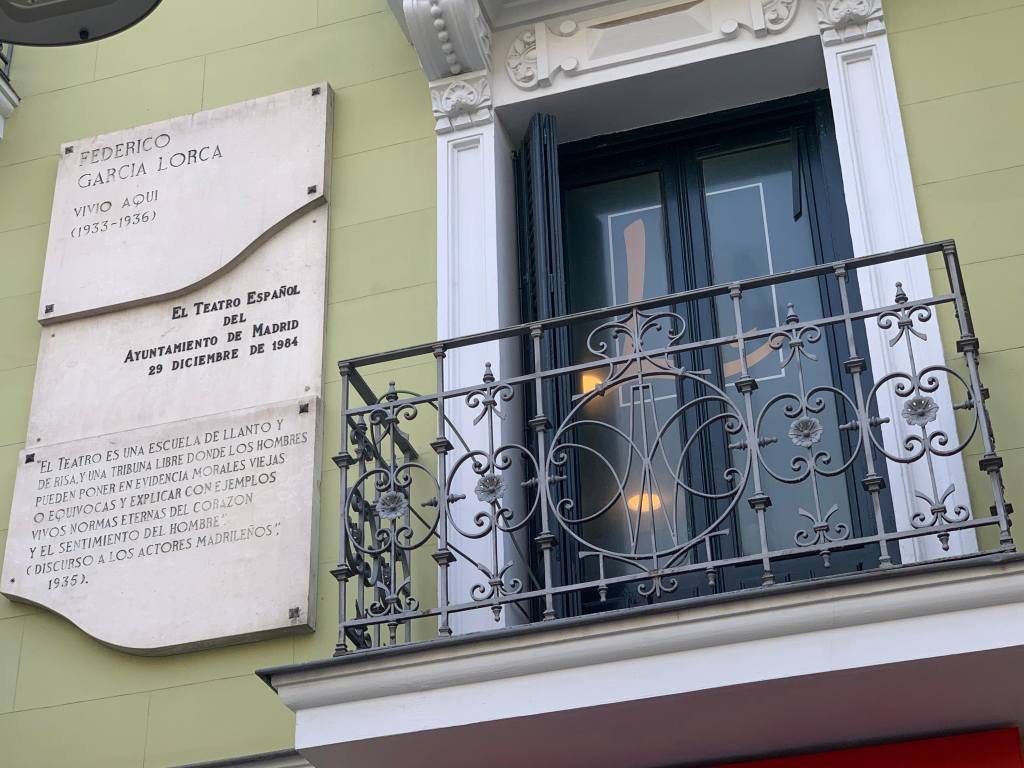

Now, for the very serious Lorca fan, there are also some sites to visit in Madrid. There is a lovely statue of the poet in the plaza de Santa Ana, and on Calle de Alcalá 96 there is a plaque which marks the apartment where Lorca lived for the last three years of his life. Another worthwhile visit is the Residencia de Estudiantes, where Lorca lived as a student along with his Dalí. The two were very close as young men, though many have criticized Dalí’s later reconciliation with the Francoist regime as a betrayal to the memory of his friend.

But, of course, the most important thing is not to follow in his footsteps, but to keep reading and performing his works. This way, he will remain forever alive.