This is part of a series on New York City museums. For the other posts, see below:

- The Frick

- The Morgan

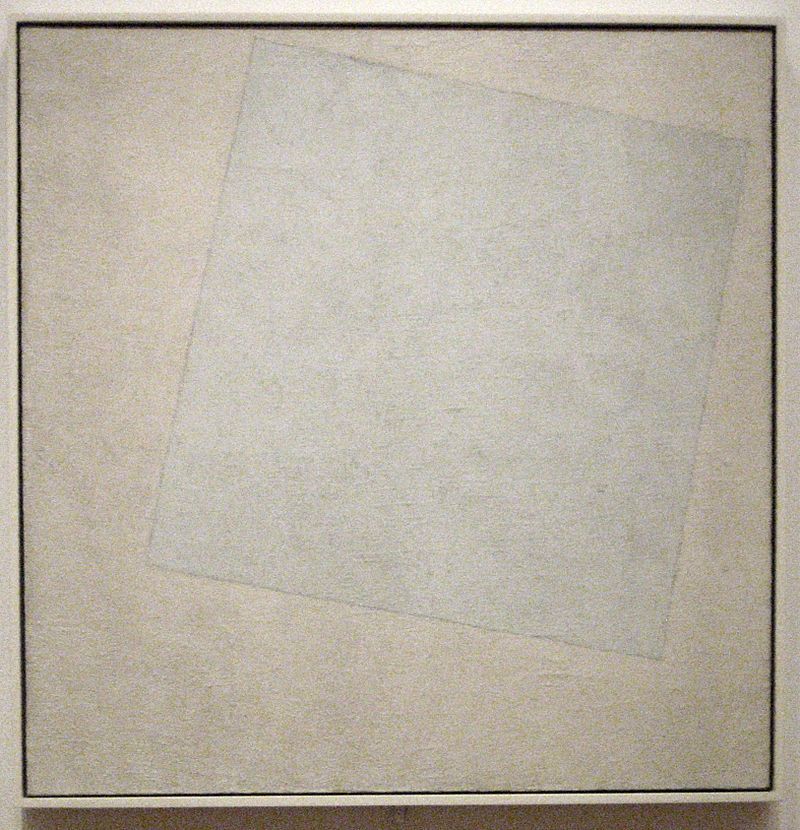

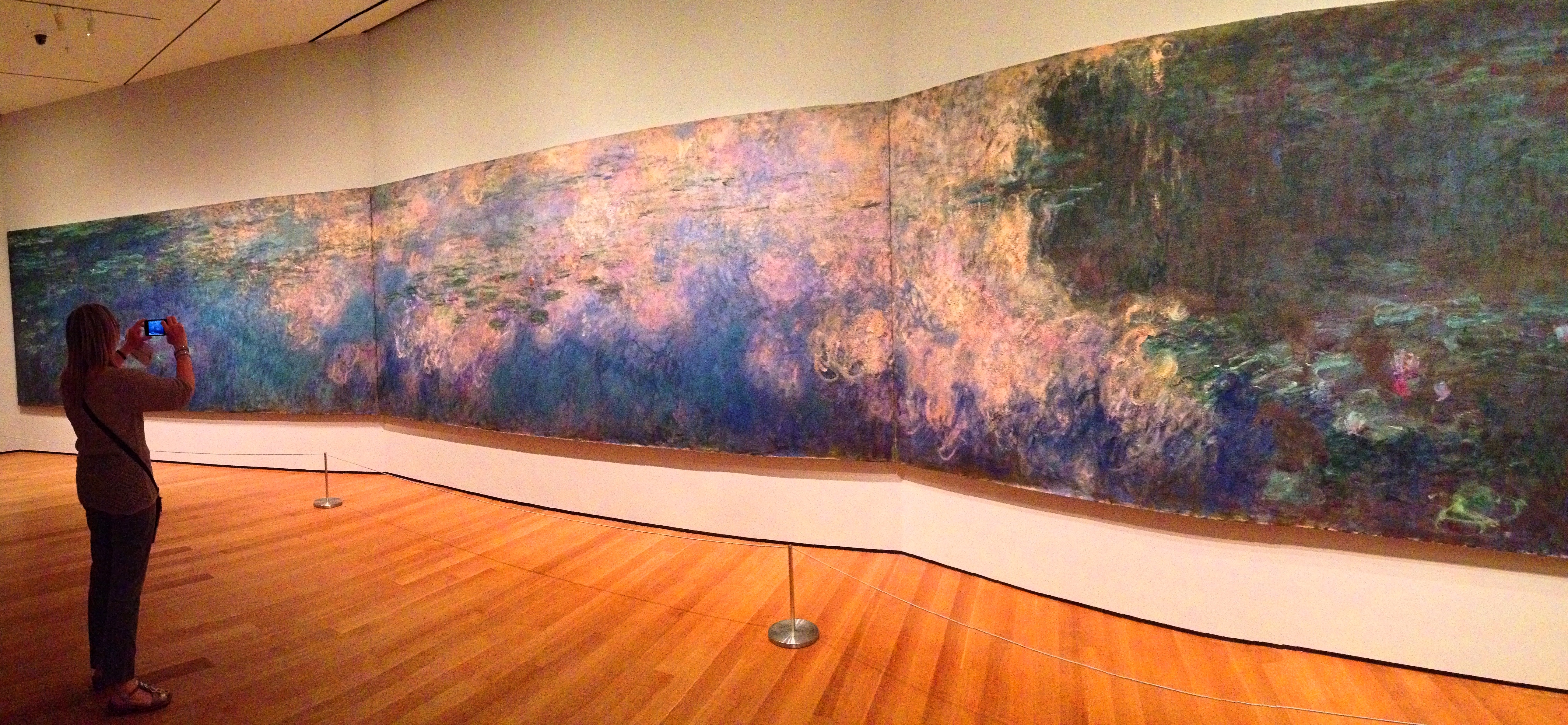

- The MoMA

- The Cloisters

- The Museum of Natural History

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art

There is no place in New York City to which I have a more intimate connection than the American Museum of Natural History. I practically grew up inside its walls. For a nerdy boy on the Upper West Side, it was the perfect place for a weekend outing. My mom recalls taking me there and letting me run around in the big Hall of Ocean Life, while she enjoyed a beer at the refreshment stand. (They do not sell beer anymore.) My dad took me plenty of times, too, and then followed up the visit with a meatball subway sandwich.

Kids still love the museum. The natural world, after all, is far more accessible than the highfalutin world of art. A child who is still figuring out the basics of the world around her has no need of elaborate images to reconnect her to her senses. And it is fortunate for our society that the museum is so accessible to children. Judging from the case of Carl Sagan, Stephen Jay Gould, or Neil deGrasse Tyson (as well as myself) the fascination exerted on youthful visitors to the museum often matures into a fascination for the natural world and a respect for the power of human reason. And you do not need to be a child to feel this twin amazement at world without and the intelligence within. I feel it every time I visit.

You can enter the museum from several spots. The grandest is, without a doubt, through the Roosevelt Rotunda on Central Park West. When walking up the stairs, the visitor will notice the heroic equestrian statue of President Theodore Roosevelt. It is worth pausing to continue this statue, for it encapsulates much of the controversial history of the institution. The mustachioed man is flanked by a Native American and an African man, both on foot, and both looking rather dejected to my eyes. The racial message is clear: the white man sits atop the lesser races. To its credit, the AMNH is acknowledging this imagery with a special exhibit, “Addressing the Statue.” I think this strategy is far preferable to the idea of simply removing it, since now the statue provides an opportunity for learning.

Theodore Roosevelt holds a special place in the history of the museum. His father was one of the museum’s founders, when it was still housed in the Arsenal Building of Central Park. The younger Roosevelt was himself an ardent naturalist, and we have him to thank for many of our country’s most beautiful national parks. But being a nationalist in those days did not mean what it means today. Roosevelt did an awful lot of hunting on behalf of the museum, providing some of the exotic animals that were later stuffed and mounted in the amazing displays. Our views on hunting big game and on racial differences have both, fortunately, evolved since then.

To thank the President for his support, the museum is studded with acknowledgements. The most extravagant of these is the massive mural painted by William Andrew Mackay, covering three tall walls of the Roosevelt Rotunda, where the visitor enters. These depict the eventful life of the naturalist president, turning him into a kind of secular saint on the walls of the cavernous room. But of course most people’s attention is absorbed by what is happening in the middle: the dramatic encounter between a brontosaurus protecting its calf, and the hungry allosaurus prowling for prey. Both the baby and the predator are dwarfed by the gargantuan form of the brontosaurus, whose already significant height is bolstered by standing on its hind legs. Personally I doubt that such a massive animal could perform such a maneuver without breaking its legs. Indeed, replica fossils had to be used, since the real fossils (made of stone, after all) are too heavy to mount in such a way.

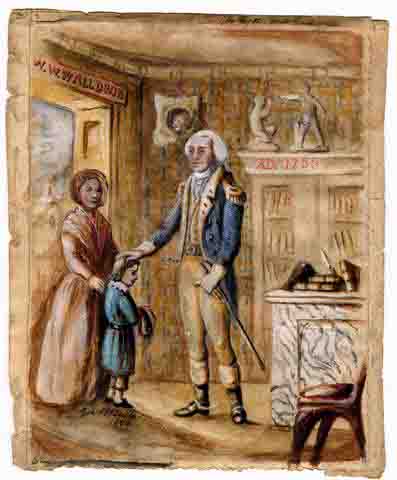

Much as I would like to move on to the museum’s exhibits, there is one more relic from the museum’s past that deserves comment. Downstairs from the glorious Roosevelt Rotunda is the Roosevelt Memorial Hall, which includes four small exhibitions about the varied activities of the president: his interest in nature; his love of exploration; his time as a statesman; and his life as a writer. What draws most attention, however, is a diorama showing a meeting between Peter Stuyvesant—the Dutch leader of what later became NYC—and the indigenous Lenape people. Made in 1939, this diorama contains several omissions and inaccuracies that work in the Europeans’ favor, such as showing the Lenape almost nude. Again, to its credit, the AMNH has included annotations on the glass, pointing out several of these problems; and their website includes lesson plans to help visiting teachers use the diorama.

I am dwelling on these examples of the museum’s less noble past, not to portray the institution in a negative light, but to show that the museum is working to improve itself without burying its past. It is a model to imitate. And the museum has a long history. This year, 2019, marks the 150th anniversary of the institution. This makes the AMNH one year older than the Metropolitan, which was founded in 1870.

Now it is finally time to enter the museum. Luckily, the entrance fee is still a suggested donation for all visitors, so you need not break the bank. What should we see first? There is a great deal to choose from. In fact, the AMNH is the largest natural history museum in the world, with millions upon millions of specimens of animals, fossils, minerals, artifacts… It would be virtually impossible to see the entire thing in one day. For my part, it has taken me dozens of visits to fully wrap my mind around the museum; and even a lifetime would not suffice to learn all it has to teach.

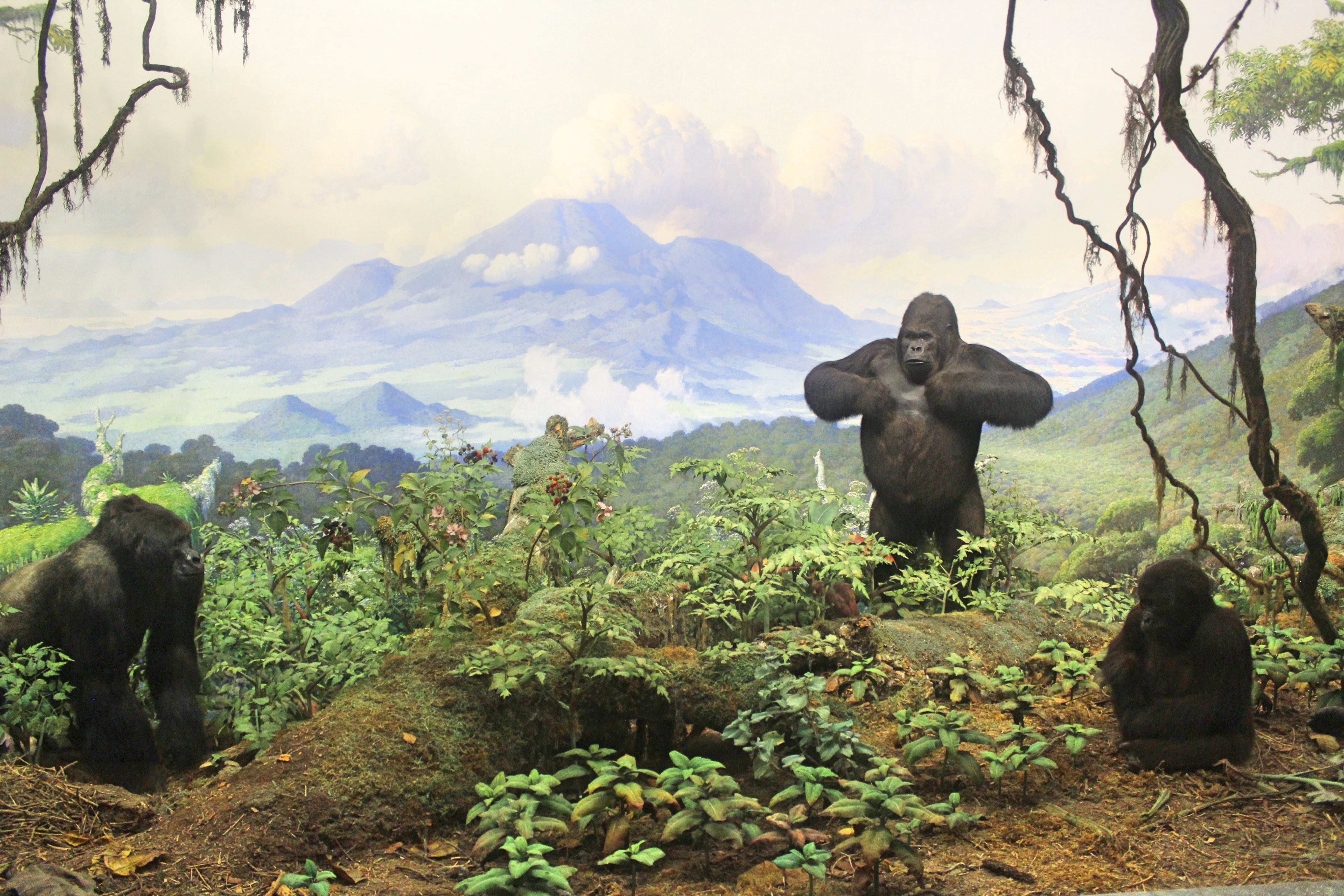

Let us go on straight ahead from the Roosevelt Rotunda into the Hall of African Mammals. Simply as a work of art, this is one of the high points of the museum. In the center a herd of eight African elephants—bulls, cows, and calves—huddle together. Arranged around this heard, in little niches in the walls, are other exotic animals: lions, zebras, giraffes. The visitor would be forgiven for thinking that all of these were merely plastic replicas; but they are real taxidermied specimens of animals (one of the elephants was shot by Theodore Roosevelt himself). This gives the dioramas a kind of macabre air, which is combined with melancholy when examining endangered species such as the rhinos and the gorillas.

Yet art intervenes to uplift this collection of exotic bodies into a thrilling exhibit. Every diorama is masterfully done: the animals stand in dramatic, lifelike poses amid an environment so scrupulously recreated as to be totally convincing. Added to this are the paintings on the curved surfaces enclosing the dioramas. These hand-painted backgrounds are worthy works of art in their own right: adapting perspective to the wall’s curvature in order to create a nearly seamless continuation with the scene in the foreground. The result is a strange blend of natural beauty and human invention, which is at turns convincingly lifelike and technically astounding. As I walked along from diorama to diorama, I felt like pilgrim visiting a church, walking around from chapel to chapel.

The lion’s share of the credit for this work goes to Carl Akeley, who participated in both collecting and mounting these specimens. Though this business of big-game taxidermy can seem to us in the present day as grim and barbaric, I think that Akeley deserves to be viewed as an artist of high ability. Creating compelling nature dioramas is no easy matter. It requires a naturalist’s eye for fact and a sculpture’s eye for form. To construct a compelling design that is, at the same time, true to nature, requires a special knack. Akeley was a master of it.

A kind of sister to this gallery is the Hall of Asian Mammals, also accessible through the Roosevelt Rotunda. This is a decidedly smaller space; and as the plaque on the wall informs us, the animals here are owed to a “Mr. Ferney” and a “Colonel Faunthorpe,” who made six expeditions into Asia to hunt these animals. Two Asian Elephants stand in the center of this gallery, slightly smaller than their African counterparts. This gallery originally contained a specimen of a giant panda and a Siberian tiger, but the subsequent history of those species led the museum to place these in the Hall of Biodiversity as examples of endangered species (more later). On my latest trip, I learned that there is a type of Asian Lion with a rangy mane, which lives in a small sliver of India.

Now let us descend a flight of stairs once again to the Rockefeller Memorial Hall, on the ground floor. Here we can enter the space directly below the Hall of African Mammals: the Hall of North American Mammals. We find still more superb animal dioramas. The most famous of these is the Alaska Brown Bear. Two of these stand behind the glass. One is reared up on its hind legs, while the other prowls menacingly nearby. The height of the upright bear is startling. Standing before it, you feel how easily this creature could overpower you. Another superb display is of the moose, which features two bull moose jousting with their antlers. As a Canadian friend once told me, moose are the “king of the beasts.”

A quick trip through the Roosevelt Memorial Hall will lead us to one of the museum’s newer spaces: the Hall of Biodiversity. Opened in 1998, it did not exist when I was a young child. The room has a stunning design. Through the center is a swath of artificial rainforest, made to replicate one of earth’s most diverse environments. A legion of tentacled creatures hang from the ceiling, including a giant squid, an octopus, and a massive jellyfish. A glass case holds the giant panda and Siberian tiger, among others, as examples of endangered species; and the bones of the long-dead dodo can be found. Most of the action takes place on the far wall, which is illuminated from behind. Here is represented the entire panoply of life, from bacteria, to algae, to fungi, to plants, and finally to all the many variations of animals: worms, insects, crustaceans, mollusks, and vertebrates of every kind. (There is an online version that you can click through.)

The sheer abundance of models on display gives a visual illustration to the richness of life on this planet. This amazing variety, developed over 3 billion years of evolution, goes far beyond our humdrum ideas about plant and animal types. To give an example, once a teacher of mine asked everyone in class to make a guess at how many species of bee there are in the world. People’s guesses ranged between 12 and 300. The answer is 20,000. Unfortunately, this biodiversity is being dramatically curtailed through human action—which is why this gallery was made.

This attractive space opens up to what has always been, for me, the most dramatic room in the museum: the Hall of Ocean Life. Here is where I would spend most of my time as a child. This hall is one of the biggest spaces in the museum. It is dominated by the life-sized model of a blue whale, the largest animal to ever exist on the planet, hanging from the ceiling. This lightweight model weighs no less than 21,000 pounds—so just imagine what the real animal must weigh. It is frankly stupefying that something so large can be alive. The entire herd of elephants from the Hall of African Mammals can huddle underneath its belly.

Dioramas line the walls of both floors of this hall. The best of these are on the bottom, where you can find a polar bear, a pod of walruses, and a huddle of sea lions. Here, as elsewhere, these displays are amazingly dramatic and lifelike. We can see the sharks in pursuit of the poor sea turtle, and the dolphins jumping out of the water to catch some flying fish. But the real masterpiece of this hall is the battle between the sperm whale and the giant squid. The sperm whale is the biggest toothed predator in the world, and its prey is likewise large. This big-headed mammal dives deep under the water—sometimes over a mile deep, going more than an hour without breathing—in order to prey on the invertebrate monsters that lurk below.

The most notable foe of this whale is the giant squid, itself one of the world’s largest animals, capable of growing to over 40 feet in length. When a whale finally catches on of these squids, it must be a serious fight, as the suction-cup scars found on the hide of sperm whales attest to. The diorama evokes all the drama of this encounter. We arrive once the fight has commenced: the whale has one of the squid’s tentacles in its jaws, and the squid is wrapped around the whale’s enormous head. The diorama is illuminated in a semi-darkness that recalls the inky blackness of the deep ocean

As a child, I found this scene both fascinating and terrifying, and became obsessed. I drew the battle over and over, doing my best to perfect the two different forms: the smooth blue whale and the sprawling red squid. Even now, this conflict between the big-brained sperm whale and the monstrous giant squid calls to mind a deep conflict within our own nature.

This description only touches upon the strange, otherworldly beauty on display in the Hall of Ocean Life—a beauty that captivated me as a child and which still moves me. The world below the seas is more fantastic and alien than anything dreamed up in science fiction. You can see this clearly in the three dioramas depicting life in the ancient oceans: creatures whose bodies form spirals, cones, wings, prowling about on an ocean floor populated with blooming anemones. The colorful, twisting, bulbous forms of the coral reef also evoke this strange allure. A part of me has always wished to be a marine biologist.

Now we will leave the Hall of Ocean Life to travel back through the Hall of Biodiversity, to enter a space which I have still not adequately explored. The first is the Hall of North American Forests. This space is dedicated to the sorts of environments present in the United States and Canada, from the deserts of Arizona to the cold forests of Ontario. The most impressive object on display is a cross section from a 1,400 year-old Sequoia. It is enormous: big enough to serve as a dance floor or even to serve as the foundation for a house. Notable historical events are marked on the tree rings, going from the invention of book printing in China (in 600), to the crowning of Charlemagne (in 800), to the death of Chaucer (in 1400), to the ascension of Napoleon (in 1804), to when the tree was finally cut down, in 1891.

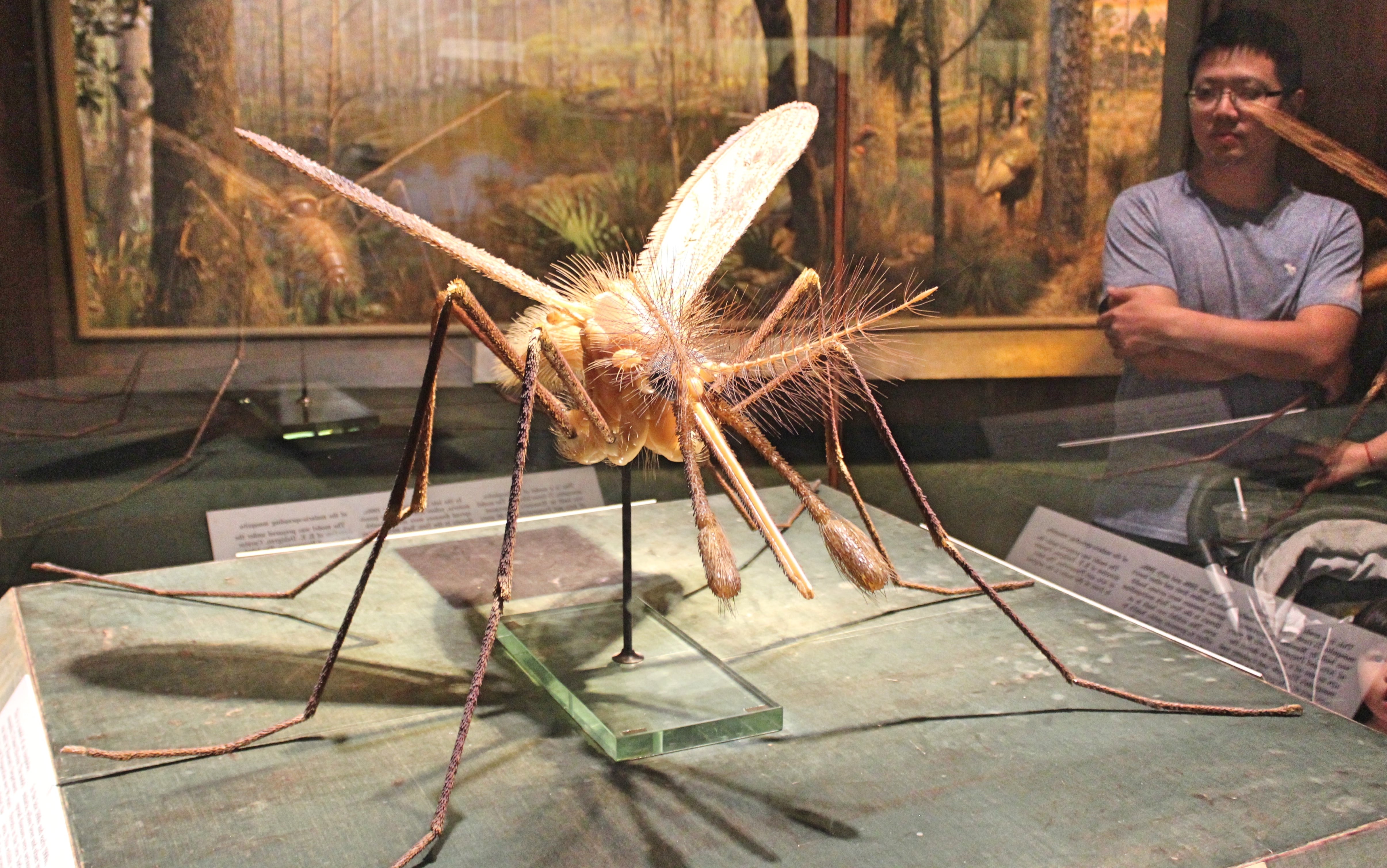

This hall is also notable for a diorama depicting the little critters who live in the soil, responsible for breaking down organic matter and keeping the cycles of life in swing. The worm, centipede, and daddy-long-legs are blown up to 24 times their actual size, which is not a pleasant sight. The same can be said for the giant model of a malarial mosquito, which does not increase my affection for that species. Teddy Roosevelt played a part in educating the public about the role mosquitos play in spreading malaria, since he had to deal with the disease when overseeing the Panama Canal.

When we leave this hall, we enter yet another of the museum’s grand entrance spaces. This is named, appropriately enough, the Grand Gallery. It is most famous for the hanging Great Canoe, made by the peoples of the Pacific Northwest. Carved from a single tree, this enormous boat can hold a dozen people and is suitable for use in ocean waves. The front features an exquisite painting of a killer whale. When I was a boy, I normally entered the museum here. At the time the canoe was filled with the plastic figures of Native Americans; and I would look at these mannequins with a kind of uncomprehending terror, since I could not figure out what those men were doing. The museum has since refurbished the canoe and removed the figures, hanging it higher so as to make the decoration more visible.

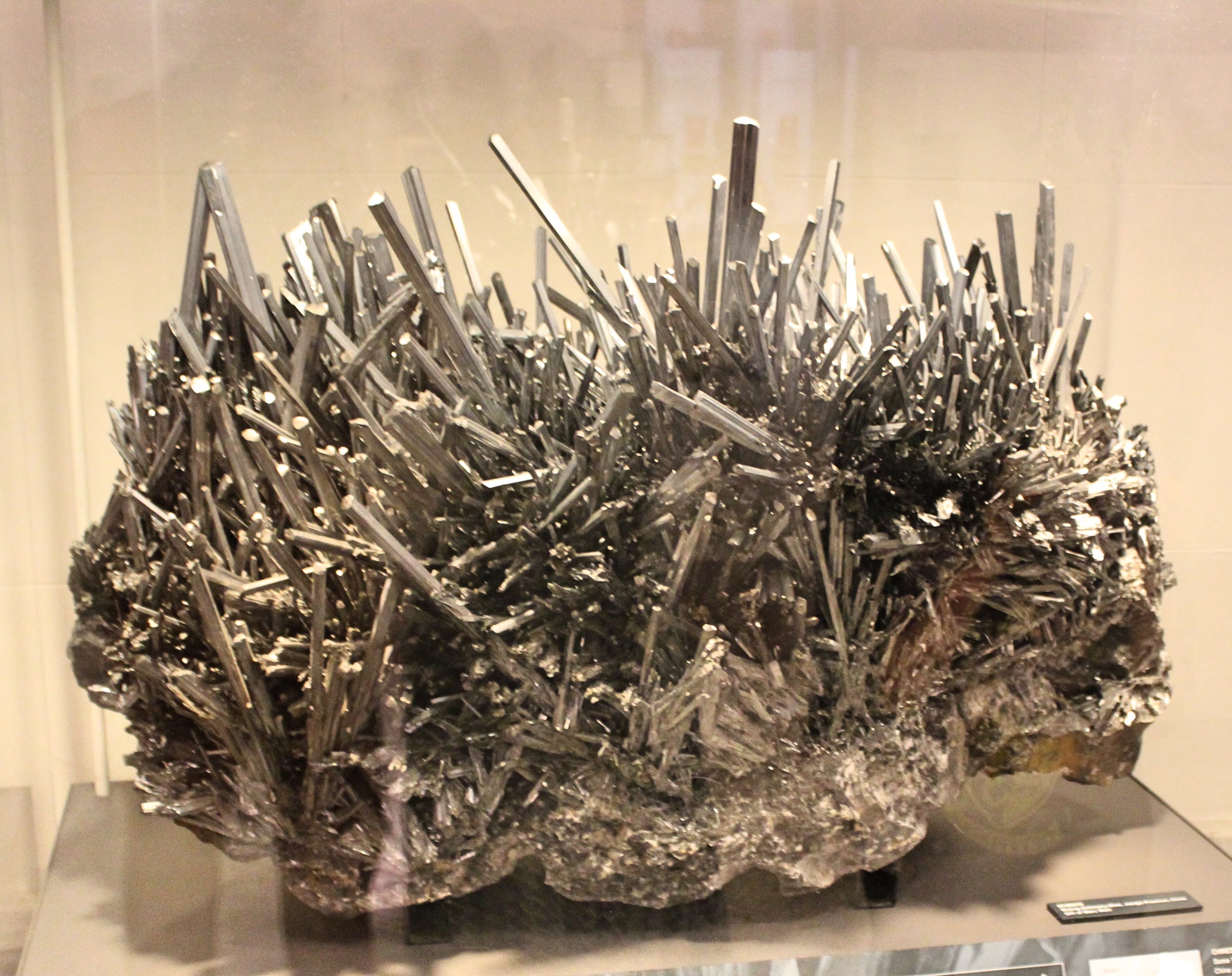

There are still other treasures to be found in this gallery. In one corner is a glass containing an ammonite fossil. This are extinct mollusks which looked like squids living in a spiral shell. This particular ammonite happened to fossilize under high pressure, which resulted in it being an iridescent rainbow. Nearby is a magnificent stibnite: a metallic crystal formed from antimony and sulfur. These crystals form themselves into a collection of jagged silver spikes all sprouting from a central core. A nearby child compared it to a porcupine.

The Grand Gallery normally leads to the Northwest Coast Hall; but it is currently closed for renovation. This hall is the oldest continued exhibit space in the museum, having been opened in 1900. The peoples of the Pacific Northwest are known throughout the world for the high quality of their visual art, including the iconic totem pole. This hall contained a great many of these poles, among other art, which made it one of the museum’s more beautiful spaces. Much of this was collected by the pioneering anthropologist, Franz Boas, during the famed Jesup North Pacific Expedition of 1897 – 1902. The current renovations are yet another example of the museum’s attempt to confront its past: updating the information to reflect how these cultures wish to be represented, rather than how anthropologists represented them 100 years ago.

The Grand Gallery also leads into the equally grand Hall of Human Origins. Opened in 1921, this hall was the first exhibit about the controversial topic of human evolution in the United States. The hall still performs this admirable task, teaching visitors about the evolutionary past of our own species. The visitor is first confronted with three skeletons, one of a modern human, one of a chimpanzee (our closest living relative), and one of a Neanderthal (our nearest extinct cousin). On the wall there are models of various primates, with their genetic similarity to humans shown underneath. Chimpanzees are nearly identical, with 99% similarity.

A major highlight are casts of famous human ancestor fossils, including Turkana Boy and Lucy. (I myself studied human evolution in the Turkana Basin, so it is always gratifying to see the plaque about the region.) There is also a reproduction of the Laetoli Footprints—imprints preserved in volcanic ash 3.5 million years ago, showing clear evidence of bipedalism—and a diorama of the what the two australopithecus may have looked like as they walked across the ashy plain (the male with his arm snuggly around his mate). There are also scenes representing the life of early humans, building shelters out of mammoth bones or being ambushed by giant hyenas. It was a tough life back in the paleolithic.

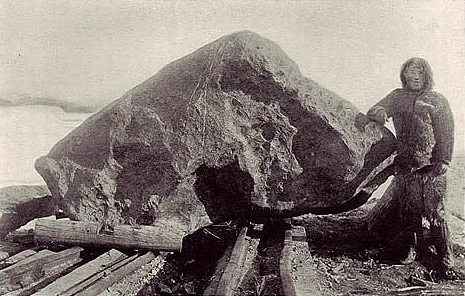

After moving through the Hall of Human Origins, you come to the Hall of Meteorites. This is most notable for containing a large chunk of the Cape York Meteorite. It is unknown when this iron meteorite struck the earth (near Cape York, in Greenland), though it was likely thousands if not millions of years ago. The original meteorite broke up into three large pieces, which were used by the Inuit living nearby to make iron tools. For decades Westerners searched for the mysterious source of iron (not easy to come by in the arctic), until Robert Peary, the explorer, finally found the meteorites and arranged for them to be transported and sold to the AMNH (likely without compensating the Inuit). The fragment displayed is so heavy that the foundations for the platform had to be built down to the bedrock below. It’s an awfully big rock.

The Hall of Meteorites normally leads to the Hall of Gems and Minerals. However, this hall is closed for renovations at the moment, which does not surprise me, since every time I visited the hall struck me as looking decidedly retro. The angular, geometrical design of the room (which appropriately mirrors that of a crystal) was praised highly when it was opened in the 1970s; but nowadays it looks very similar to how Kubrick imagined the future would be, in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Nevertheless, this is one of the most beautiful corners of the museum. The glass displays, arranged throughout the room, are filled with gleaming stones—gems which reflect and refract light in a thousand distinct ways.

(Visit here to see photos of the original gallery and concept drawings for the new gallery.)

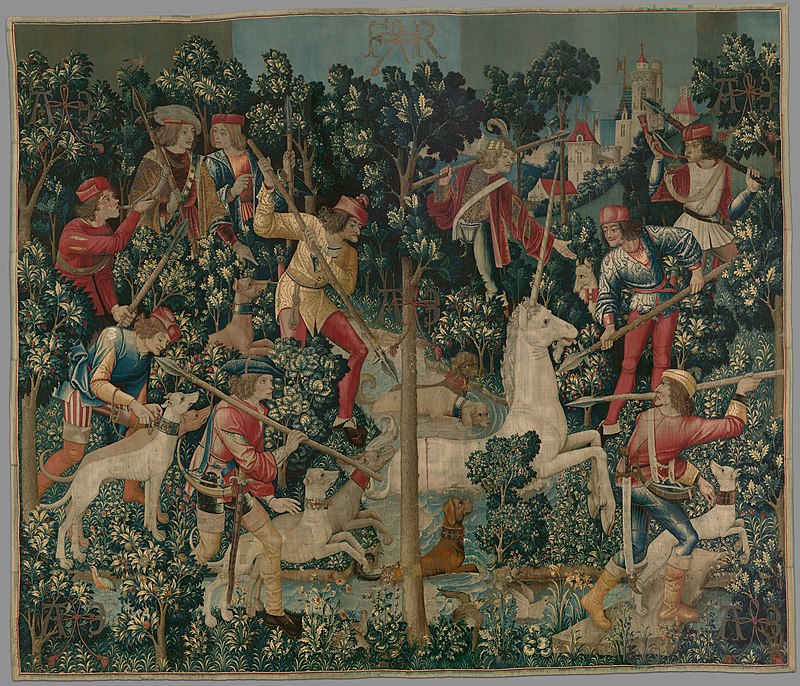

This hall has a colorful history. Whenever I visit, I think that the hall looks like the kind of place Lex Luther would rob in order to get some kryptonite. Other people have had similar thoughts, it seems. In 1964, Jack Roland Murphy (“Murph the Surf”), with two accomplices, snuck into the museum and stole some of its most famous pieces: the Eagle Diamond, the DeLong Star Ruby, and the Star of India sapphire (all donated to the museum by J.P. Morgan). The thieves were eventually caught, and the jewels found and returned to the museum—the Star of India was found in a bus station foot locker—with the notable exception of the Eagle Diamond, which was likely cut into smaller pieces and sold. (Murph the Surf was later convicted for murder; in prison he became a minister and was released early; he is currently the vice president of the International Network of Prison Ministries.)

We have gone to the very end of the museum, but we have still left out one of the museum’s most notable wings: the Rose Center for Earth and Space. Opened in 2000 (so I did not see it as a child) this is the newest part of the museum, and it shows. The space-age design features a massive central sphere enclosed in a glass cube. The new Hayden planetarium is housed within this sphere, where visitors can see shows projected on the upper dome. Neil deGrasse Tyson is the first and, so far, the only director of the Rose Center; and he narrates many of the astronomical shows.

Below this “cosmic cathedral” (as the designer called it) is the Hall of the Universe. Here you can find information about stars, planets, galaxies, and the moon, all displayed on sleek metallic panels. There are scales that tell you what your weight would be on Mars and the Moon (in pounds, which requires a conversion for non-American visitors). In one clear glass case there is a self-contained ecosystem of algae and tiny shrimp—a microcosm that represents the macrocosm of earth. A curving walkway that leads away from the planetarium takes the visitor through the entire history of the universe, from the big bang to the present day.

The star of the hall is the Willamette Meteorite. This is another iron meteorite, yet it looks strikingly different from the Cape York Meteorite. Its surface is pockmarked—I believe from centuries of weather erosion. The rock has been on earth a long time. Possibly the core of an early proto-planet, smashed to smithereens in a cosmic collision, this meteorite struck earth thousands of years ago (but we have yet to be able to find the impact sight). It was found in Oregon, but it was likely moved by expanding and receding glaciers. As with the Cape York Meteorite, the Willamette Meteorite was taken without the consent of the native peoples who had long known about it. This led to a lawsuit, in 1999, by the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon, demanding the return of the rock (which had been in the museum for nearly 100 years by then). Luckily, the AMNH reached a deal that allowed it to keep the meteorite.

Adjoining the Hall of the Universe is the Hall of Planet Earth, devoted to geology. This gallery has accomplished the difficult job of rendering geology visible, tactile, and immediate. The space is filled with models of geological formations, many of which can be touched. These slices of earth help to illustrate the normally invisible processes below the surface which have shaped our planet—the slow churning of the continental plates, the effects of receding glaciers and running water, the volcanic explosions which hurl up new land from the depths. The hall also has a section devoted to climate change, which features an ice core (a piece of ice formed over thousands of years) which the visitor can “read” by moving a monitor over different sections, thus revealing how the climate has changed.

From what I observed, children love the Rose Center for Earth and Space. Everywhere I looked young kids were reading, looking, touching, laughing, and in general having a great time. To me this represents an accomplishment of a high order. Making whales and dinosaurs accessible to children is straightforward; but to make accessible the abstract theories of physics, the slow processes of geology, and the distant threat of global climate change—this calls for subtlety and skill, and the designers of this hall have accomplished their task with brilliance.

Now we must get to an elevator and ascend from the bottom to the top floor. We have dallied in the museum for a good, long time, and it will close soon, so we had better get to the spectacular fossil rooms on the fourth floor.

The proper place to begin is on the Orientation Hall. Here the visitor can see a video that explains some background of evolution and cladistics (making evolutionary trees). But the visitor will likely have difficulty focusing on this video, since in 2016 the museum added an enormous dinosaur to the room. This is the Titanosaur, a massive, long-necked sauropod whose form dominates the space. From tail to head, the animal stretches 119 feet (or 32 meters); and in life it likely weighed well over 60 tons (an adult elephant, by comparison, weighs about one-tenth as much). The size of these animals is simply staggering—especially considering that they began life in an egg scarcely bigger than that of an ostrich. How much vegetation did one of these have to eat in a day in order to survive?

The fossil rooms make a closed circuit, so the visitor can go in any direction. The most logical direction to go in, however, is to begin with the Hall of Vertebrate Origins—since this way the galleries are chronological.

From the perspective of biology, the Hall of Vertebrate Origins is likely the most fascinating hall of fossils, even if it lacks any of the spectacular specimens of later eons. We can see examples of the first vertebrates, on sea, on land, and in the air. One of the more memorable fossils on display are the jaws of the extinct Megalodon, a shark that lived millions of years ago, and which grew several times larger than today’s great white shark. The tremendous and terrifying jaws, hanging from the ceiling, dwarf even the bite of a Tyrannosaur. Nearby hangs a model of the Dunkleosteus, an armored fish that lived many hundreds of millions of years before the Megalodon, and which likely was major predator of its day. Further on is a Pterosaur, a member of the first known vertebrates to have achieved flight. (Commonly called dinosaurs, the Pterosaurs were closely related but technically not dinosaurs. Also, the term “Pterodactyl” only refers to one subgroup of the Pterosaurs.)

These three examples only touch on the immense biological richness in this hall. For anyone hoping to better understand the history of life on our planet, their time will be well spent in close examinations of the specimens on display. The museum also offers computer booths that allow visitors to scroll through various evolutionary trees and learn more about different species.

We now come to one of the museum’s most spectacular spaces: the Hall of the Saurischian Dinosaurs. Now, Dinosaurs are typically split into two large evolutionary groups, the Ornithiscia and the Saurischia. The latter includes all carnivorous dinosaurs as well as sauropods (and birds, the only living dinosaur group). This means that this gallery includes the famous Tyrannosaur. Even when manifestly dead, the Tyrannosaur has a commanding presence. The mere thought of it being alive is enough to cause goose bumps. And this predator—one of the largest to have ever walked the earth—was likely even more terrifying than we normally think. According to the paleontologist Stephen Brusette, Tyrannosaurus was highly intelligent, had excellent vision, and likely lived and hunted in packs. One of them is frightening enough; imagine a gaggle of T. Rex. And to think that this fearsome creature began its life no bigger than a chicken.

Across from the Tyrannosaur is another museum favorite, the Apatosaurus (sometimes called the Brontosaurus). This is a sauropod, somewhat smaller than the Titanosaur in the other room, but still large enough to make even the Tyrannosaur look petite by comparison. Another fearsome predator on display is the Allosaurus, a carnivore somewhat smaller than Tyrannosaurus that lived several million years earlier, which was an apex predator in its own epoch. This Allosaur is bending over to scrape some meat off of a fresh carcass. One less flashy specimen on display is the skull of a velociraptor (which, despite its portrayal in Jurassic Park, was about the size of a turkey).

Next we come to the Hall of the Ornithischian dinosaurs. This group does not contain quite as many star dinosaurs as the other hall, but it will not disappoint. Here can be found one of the museum’s most important specimens, a mummy of a duck-billed dinosaur. Unlike in the vast majority of dinosaur remains, here we do not only have the skeleton, but the skin of the ancient animal. This has allowed scientists to get a much better idea of what the scales of a dinosaur were like. Also on display is a Stegosaurus, famous for its small brain, spiked tail, and a back covered in vertical plates (whose purpose is still debated). My personal favorite, however, is the Triceratops, an herbivore that lived alongside T. rex and was one of its principal foes. Powerfully built, with a three-pronged horn and a protective ridge, hunting these beasts must have been no easy matter.

I am always moved by the dinosaurs. They were magnificent animals, many of them so far beyond the range of size and power that we can find among today’s land mammals and reptiles. That such a diverse group of powerful beasts could go entirely extinct from a chance event—a meteoric bolt from the blue—cannot but remind us of our own precarious existence. Indeed, these chance catastrophes play a disturbingly crucial role in the history of life on our planet. Dinosaurs themselves would never have become so dominant if not for the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event (possibly caused by volcanic activity), which eliminated much of their competition. And the mammals would never have been able to emerge as the current dominant life form if not for the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event, which eliminated every one of these creatures (except for birds), thus leaving the stage set for us. But how long will we last?

The next hall focuses on the early history of our own clan, the mammals. The further back one goes in evolution, the mudier become the distinctions between distinct lineages. Thus, some of the fossils on display in the Hall of Primitive Mammals do not strike us as mammals—and in fact are not, only early relatives. Into this class falls the Dimetrodon, a sail-backed cuadroped that looks far more reptilian to my eyes than anything resembling a house cat. But a close examination of its skull reveals the tell-tale opening behind its eye socket, leaving a bony arch which scientists have decided constitutes the defining mark of a new class of animal, the Synapsids, which includes mammals.

The Hall of Primitive Mammals is notable for the mammal island—a large array of fossil specimens that illustrate the range of mammalian diversity. By any measure, we mammals are an immensely diverse lot, having populated the land, sea, and air, occupying all sorts of niches, and ranging in size from a large insect (the smallest bat) to the biggest animal ever to exist (the blue whale). Amid this sea of variety we find the Glyptodont, an extinct relative of the armadillo, far larger and far more heavily armored. The face of this fossil preserves a sense of the patient drudgery which must have characterized this poor beast’s life, as it dragged its heavy shell through the landscape. The saber-toothed cat led a more exciting, if not more successful, life thousands of years ago, as did the lumbering cave bear. But the most terrifying skeleton of all may belong to the Lestodon, an enormous ground sloth whose gaping nose socket seems to look at you like a cyclops.

Finally we come to the Hall of Advanced Mammals, which features species more recently extinct (many of which died off during the great megafauna extinction 10,000 years ago). Here we can see a large array of specimens that illustrate the evolution of horses, growing up from dainty things the size of dogs up into the stallions of today (though, as often happens with evolution, this progress was not always linear). At the end of the hall we see extinct relatives of the elephant. One is the mastodon, which is about the size and build of a modern elephant, if slightly stockier. This nearly complete fossil skeleton was found in New York—amazing to consider.

Standing a head taller is the Mammoth, a much closer relative of the elephant that went extinct not too long ago, while the Mesopotamian and Egyptian civilizations were well under way. It is massive, of nearly dinosaurian proportions, with tusks that curve so tightly inward that it seems they would have been useless for defense. (Scientists are now playing with the idea of using DNA from frozen mammoth remains to bring them back. I wish them luck.)

By now, you must be exhausted. Museum fatigue has set in, and you can no longer concentrate on or even enjoy what you are seeing. This is inevitable at the American Museum of Natural History. There is just way too much. I have already written far, far more than I planned to, and there is still so much of the museum left to explore. I have left out the Hall of Reptiles and Amphibians, the Hall of North American Birds, and the Hall of Primates. And that is not all. The museum has huge exhibits devoted to cultural anthropology. Aside from the aforementioned Northwest Coast Hall, there is the Hall of Asian Peoples, the Hall of African Peoples, the Hall of Mexico and Central America, and the Hall of South American Peoples.

And here I must add a note of criticism. It says a great deal that a museum of natural history would include exclusively non-Western cultures. Admittedly, this is largely a historical artifact of the time when the study of “primitive” living peoples was grouped with the study of human evolution and primate behavior in the discipline of “anthropology.” This grouping obviously reflected cultural and racial biases of the original founders of the field. But we have moved far beyond that, and now it seems discordant and strange to walk through, say, the Hall of Asian Peoples. How could a single hall, however well-made, encompass the enormous history and diversity of the Middle East, Central Asian, Southeastern Asia, and East Asia? Even encompassing the traditions of China alone would require a museum for itself. Not only that, but the cultural halls generally have a dark and dingy aspect, as if they have been left unchanged for decades.

So it is my hope that the museum soon refurbishes, not just the Northwest Coast Hall, but all of the cultural halls—taking into account not only advances in our understanding, but how the cultures themselves would like to be represented. Judging by the progress that the museum is already making in this respect, I think that the future looks bright.

What more can I say about the Museum of Natural History? I have already said more than I planned to, and yet it scarcely seems enough. My visits to the museum had a fundamental influence on me. My shifting interests throughout my childhood and adulthood—in marine biology, chemistry, physics, botany, human evolution, and human cultures—have virtually tracked the floor plan of the museum. From an early age, I have been possessed with a desire to collect, catalogue, and display—an urge which I am sure owes much to this place. Beyond its importance in my life, however, I see the Museum of Natural History as a model institution for the coming ages, as something much needed in our society, even as a kind of secular church for the new age: capable of appealing to the mind and to the emotions. I hope that every child may feel the wonder I felt, and still feel, at both the universe around us and the intelligence within, which has allowed us to know something of this universe.