This is Part Six of a six-part series on Rome, following this plan:

- Introduction

- Churches

- Basilicas

- Museums

- Ruins

- The Vatican

While I do have some scruples about including the Vatican in my series about Rome—since it technically is not a part of Rome—I think excluding it would be paying too much attention to official opinion at the expense of geographic fact.

To state the obvious, the Vatican is unique. The smallest state in the world, both by population and area, the Vatican is also distinguished for being a theocratic monarchy, governed by the bishop of Rome, the Pope. The Vatican’s economy is also unique, supported almost entirely by tourism.

The Vatican is not as old as you might imagine. In former times the Pope was as much a secular ruler as a spiritual guide; the Papacy had its own proper country, known as the Papal States—which lasted from the time of Charlemagne to the nineteenth century—which controlled a sizeable hunk of the Italian boot. This state was swallowed up by Italy during the rise of Italian nationalism after the Napoleonic Wars. The Vatican as we know it today was established in 1929 in the Lateran Treaty. It is thus only a little older than my grandmother.

Aside from the pilgrims, many millions of secular tourists visit the Vatican each year, and all of them to see three things: the Vatican Museums, the Sistine Chapel, and St. Peter’s Basilica. This is what I saw, and this is what I’m here to tell you about.

The Vatican Museums

The first thing you should know about visiting the Vatican is that you must buy your tickets ahead of time. (Here in the link.) If you don’t, you will be one of the hundreds of people waiting—probably in vain—in the enormous line that stretches out the museum’s entrance and curves around the Vatican’s walls. I felt a mixture of pity and, I admit, self-congratulation upon seeing this line, its members sweating in the relentless sun, unremittingly pestered by tour guides.

I scheduled my visit to the Vatican for my first full day in Rome. I did not trust myself to figure out the public transportation, so I walked, which took me about an hour and a half. I was so worried about missing my entrance-time that I didn’t stop to eat or drink. Added to this, it was hot and humid, and I stayed in a room without air conditioning or even a window; so I slept poorly the night before. When I arrived, I was sticky with sweat, dehydrated and dizzy, my stomach filled with foam, disoriented by the heat and sleep deprivation, my legs a bit shaky, my heart pumping like mad, my body full of adrenalin. It was, in other words, a normal vacation day for me.

The Vatican Museum is one of the largest and most visited museums in the world. Begun in the fifteenth century by Pope Julius II, it displays some of the finest pieces in the papal collection, and thus some of the most important works in Western history. There are over 20,000 works on display; I will content myself with some highlights.

The real shame of the Vatican Museum is that most tourists rush through it to get to the Sistine Chapel. I do not blame the tourists: when you have something like the Sistine Chapel waiting for you, it is hard to take your time. Nevertheless, in the process visitors walk past one of the most impressive museums in the world.

Before visiting, I had hardly an inkling of the size and scope of the museum’s collection. In the Museo Gregorio Egiziano, for example, there is an enormous collection of Ancient Egyptian artifacts, including mummies, sarcophagi, papyruses, statues, and even reproductions of the Book of the Dead; the museum boasts a similarly complete collection of Etruscan art. In another wing, much further along the visit, is a collection of modern religious art. Added to all this is a seemingly endless collection of Greek and Roman statues. In the Museo Chiaramonti, for example, such a huge number of busts and sculptures—of emperors, heroes, and gods, all white marble—are pilled up on top of one another that it seems as though you’ve wandered into a warehouse of a sculpture factory.

The museum is notable not only for its works, but for its spaces. In the Sala Rotunda (“round room”), larger-than-life statues occupy niches in a circular room, built to imitate the Pantheon; and in the middle of the room is a gorgeous ancient mosaic. The Gallery of Maps is a long hallway; the decoration of the ceiling is unspeakably ornate—totally covered in floral designs, patterns, paintings, and decorative moldings—lit up with a golden glow; and its walls, as befitting its name, are covered in a series of lovely maps of Italy.

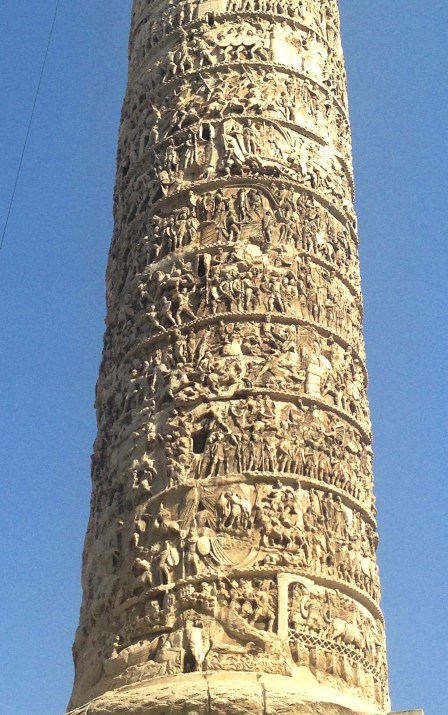

The Cortile della Pigna, or Courtyard of the Pine Cone, takes its name from the Fountain of the Pine Cone. This fountain, of Roman origin, was moved in 1608 from its original location near the Pantheon to decorate a large niche in the courtyard’s wall. (At the time, this courtyard was twice as large, and was known as the Cortile del Belvedere; the Apollo Belvedere used to be displayed here, which is where it gets its name.) In the center of this courtyard is a version of Arnoldo Pomodoro’s famous statue, Sfera con sfera—a large golden sphere, cracked and broken, with another similarly damaged sphere inside. There is also a monumental bust of Augustus, who was given a new hairdo in during the Renaissance.

Among the hundreds of excellent sculptures, my favorite is Laocoön and His Sons—a work that can also be said to be the founding piece of the Vatican Museum. The statue was made sometime around the first century BCE (we think), and later found its way to the palace of the Roman Emperor Titus, where it was praised by the Roman writer Pliny the Elder (first century CE). At some point in antiquity the statue was lost; it was only rediscovered during the Renaissance, in the February of 1506. The antiquarian and art-loving Pope, Julius II, was immediately informed of this discovery; Michelangelo went to investigate and sent an enthusiastic report of the statue; and one month later, Julius had the magnificent sculpture on public display in the Belvedere Courtyard. The statue now stands in the Museo Pio-Clementino.

The statue depicts a moment from Virgil’s Aeneid. The Greeks have given up trying to knock down the walls of Troy; instead they are following Odysseus’s sneaky plan, to gift them the Trojan Horse. The big, wooden horse is wheeled up to the walls, and the Trojans obligingly come out to admire it; soon they decide to bring the horse inside the walls. Laocoön, a priest, is the only person against this plan. “Beware of Greeks bringing gifts!” he says. At that moment, spurred on by the malevolent gods, two enormous snakes appear and strangle both him and his two sons. The Trojans interpret this as an omen, thinking that the gods disapproved of Laocoön’s skepticism. In reality, the gods were on the Greeks’ side.

The statue is extraordinary. Far removed from the Classic Greek ideals of perfect form and sublime grace, it is full of suffering and fear. The bodies are contorted and twisted, the faces scrunched up with pain; the snakes’ slithering bodies are wrapped around arms and legs, tying all the figures together into a writhing mass of limbs. Every detail is exaggerated. Indeed, the statue could have been melodramatic, even silly, if not for its perfect execution. Every detail seems just right: the arrangement of the figures, the anatomy, the posture, the expressions, the technical execution. It is one of those few masterpieces of art that impress themselves upon the memory after a split-second of viewing.

I stood for a long while admiring the work. How could so much movement be conveyed by immobile stone? How could an entire story be told instantaneously? The feeling evoked by the statue is one of gruesome tragedy. Laocoön will die even though he was right, and his sons will die even though they are innocent of any crime. All of them will die publicly, and in immense pain, for nothing, and with nothing to look forward to except oblivion. The image is much too exuberantly violent to be melancholy, much too grisly and ghastly to be beautiful. It is, rather, sublime: instead of conforming to your aesthetic sense, it overawes you, trampling over all your tastes and preconceived notions, soaring above all your attempts to measure or define it, leaving you simply dazed at the power of human art.

I could spend hours and pages in ecstasies over other works in the museum, but I will exercise self-restraint. The only other individual works I will mention are Raphael’s frescoes.

These were commissioned by that same Pope Julius II, in 1508, to decorate the papal apartments. They occupy four rooms, now called the Raphael Rooms: the Sala di Constanto, the Stanza di Eliodoro, the Stanza della Segnatura, and the Stanza dell’Incendio del Borgo. Needless to say, each one is a masterpiece and worthy of study. But by far the most famous of these are in the Stanza della Segnatura. This was the first room that Raphael completed. At the time, this room contained the Pope’s personal library, which is why Raphael set about creating intellectual allegories.

No place in the world more perfectly captures the Renaissance blending of art and science, of classical education and effective government, of pagan philosophy and Christian theology. In the Disputation of the Holy Sacrament, Raphael depicts theology as a collection of saints, popes, and religious poets engaged in a discourse on the nature of God, while Jesus and the Father sit enshrined above. In The Parnassus we find an allegory poetic inspiration, Apollo and the Muses stand with a collection of melodramatic bards and troubadours, all crowned with laurels, crowded on top of a hillside. (Dante is the only figure to be represented twice in the fresco sequence, appearing both among the theologians and the poets.) And in the Cardinal Virtues, both human and divine virtues are depicted in allegorical form, the human virtues—prudence, fortitude, and temperance—as women, and the divine virtues—charity, hope, and faith—as accompanying cupids.

The last and incomparably most famous is the School of Athens. Even if you do not know its name, it is an image you have undoubtedly seen countless times. At least three books in my library have this painting as their cover image. It is one of the iconic images of Western art: a symbol of the Renaissance, of humanism, of philosophy, of science, and of the entire intellectual tradition. Like other iconic images—The Mona Lisa, Guernica, The Creation of Adam—it is somehow unforgettable: every detail is classic, perfect, and instantly memorable, and it is carried with you the rest of your life.

In his classic documentary, Civilisation, Kenneth Clarke tells us that Raphael’s works must be looked at long and hard to be truly appreciated. Rather like Mozart’s music, Raphael’s art is so perfectly balanced, so immediately appealing to the senses, so intuitively intelligible even to the ignorant, that it seems as if they are devoid of serious substance. Raphael’s painting is just so seeable. The painting unfolds itself to you; it almost sees itself for you. The viewer is not asked to do any work, just to enjoy. Every relevant detail is taken in at a glance. Again, like Mozart’s music, everyone might agree that Raphael’s work is pretty, charming, and pleasant, but many might not guess that it is also profound.

To sense this profundity, you must learn to unsee it before seeing it again: you must fight the immediate familiarity, the apparent ease, and try to see the painting as it might have appeared to its first viewers: as striking, imaginative, triumphant, and so utterly convincing that one man’s individual vision soon became a model for classic grace.

This is, of course, much easier said than done. It is especially difficult if you are standing in the middle of a crowded room, buffeted by tour group after tour group, trying to find a good angle to photograph the painting. By this time, I was thirsty, hungry, and feeling not a little claustrophobic from the swelling crowds. I tried to look at the painting long enough to see what Clarke saw; but the contrast between Clarke calmly meditating on the painting in solitude, and myself sweating and painting in the noisy crowd, was too much to overcome. After fifteen minutes of staring, I turned and left. I was about to enter the Sistine Chapel.

Sistine Chapel

(If you want to take a virtual tour of the chapel, there is an online version that you can find here. I recommend viewing it while listening to Georgio Allegri’s beautiful “Miserer mei, Deus,” composed for performance in the Sistine Chapel.)

Stepping into the Sistine Chapel is an unforgettable mixture of sublime awe and petty annoyance. Security guards are posted all around the room, keeping the gaping tourists out of main channels, preventing the entrance and exit from getting blocked, and repeatedly reminding tourists that no photos are permitted. Hundreds of people were packed into the room, all of them standing elbow to elbow, standing singly or in tight groups, everyone with their eyes turned upwards. It reminded me of those cartoons in which turkeys drowned themselves by looking up, mouths agape, during a rainstorm.

The hushed and hurried sounds of voices, some whispering, some laughing, reverberated in the stone chamber, creating a decidedly unmeditative din. Every five minutes or so, a voice crackled onto a PA system and told everyone, in four or five languages and to respect the sacred space. This created about thirty seconds of respective silence until the talking irrupted again, and the process started over. Even in this place, the most important space in the world for Western art, a holy place for Catholics and humanists alike, we recreate the same silly dynamic as in a middle school classroom.

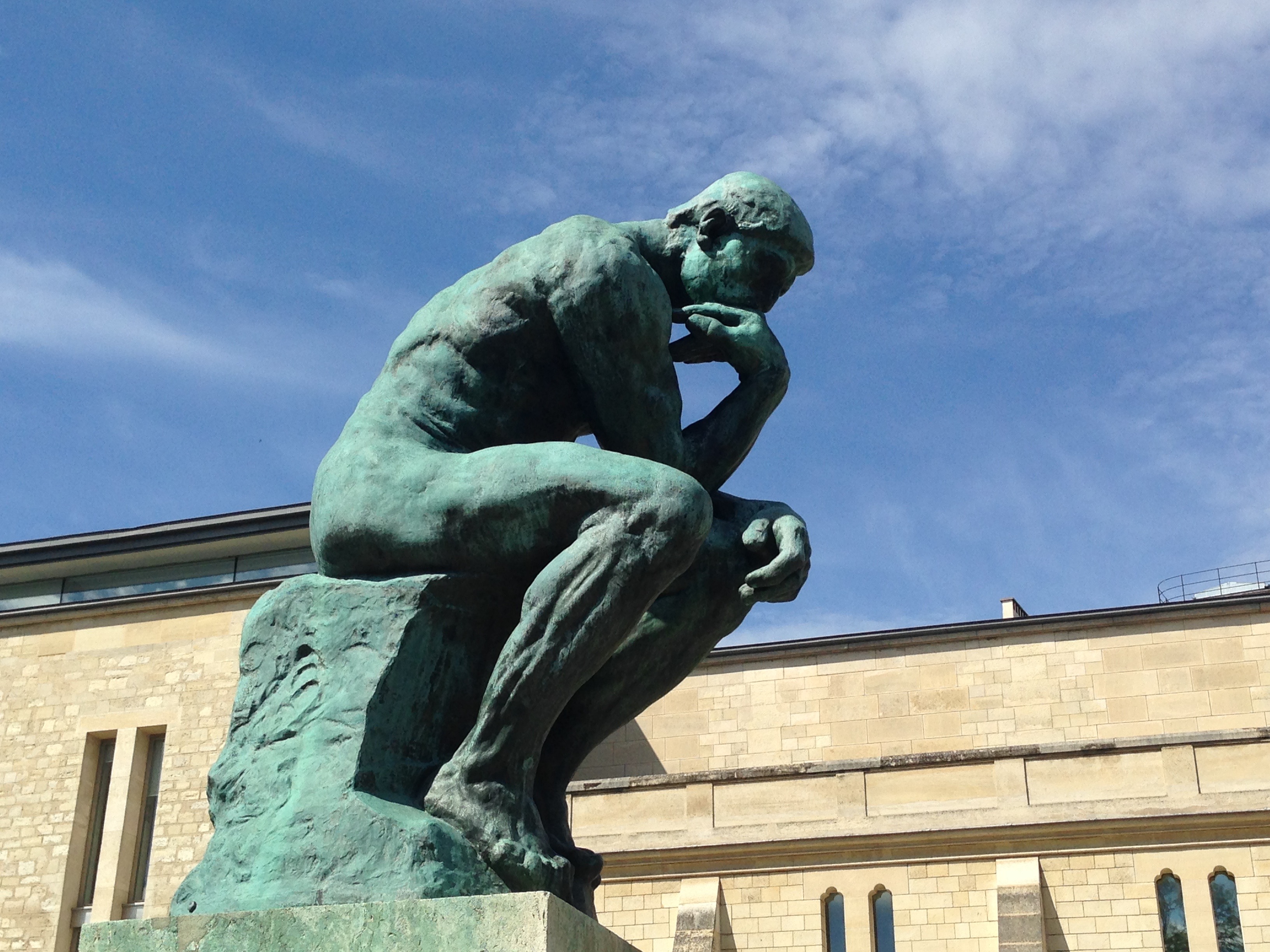

Even without Michelangelo’s frescos, the Sistine Chapel would contain enough artwork to make it a necessary visit for any art-lover. To pick just one example, Botticelli’s Temptations of Christ, an obvious masterpiece, is on one of the lower walls, along with numerous other paintings of similarly high quality. And yet it is nearly impossible to pay any attention to these paintings; indeed, I bet most visitors do not even notice them. Michelangelo’s ceiling frescos are so overpowering that you cannot look at anything else. Every visitor stares helplessly up at the ceiling, painfully craning their neck like Rodin’s statues.

The work is so famous that it seems superfluous to say anything about it. Everybody has seen it. Everybody knows the story of Michelangelo, tortuously arching his back on the scaffold, slowly and scrupulously completing the frescos almost single-handedly. Michelangelo even wrote a sonnet about his own discomfort (this is a translation by Gail Mazur):

I’ve already grown a goiter from this torture

hunched up here like a cat in Lombardy

(or anywhere else where the stagnant water’s poison).

My stomach squashed under my chin, my beard’s

pointing at heaven, my brain crushed in a casket

my breasts twisted like a harpy’s. My brush,

above me all the time, dribbles paint

So my face makes a fine floor for droppings!

(You can read the rest of the poem here.)

Both artwork and artist have been turned into one of the great creation myths of European history. The work even seems to allegorize its own heroic origin: Just as God, sublime and omnipotent, reaches out with one delicate figure to delineate the reclining figure of Man, so did Michelangelo himself give form to the ideal image of Man. Here is the perfect symbol of creativity.

The Sistine Chapel was commissioned by the same Julius II—the most important of the Renaissance Popes, perhaps—and interrupted Michelangelo’s work on the Pope’s tomb. This tomb, by the way, was never completed on the scale originally imagined. The half-finished sculptures that were to form a part of it are now considered to be among Michelangelo’s masterpieces, such as the Dying Slave in the Louvre. Although originally planned for St. Peter’s Basilica, the tomb, as eventually realized, is in San Pietro in Vincoli, a church near the Colosseum; this tomb is now most famous for its statue of Moses.

The most striking thing, aside from their awe and splendor, about Michelangelo’s frescos are their focus on man. I use “man” deliberately, because the vast majority of the figures are men, aggressively so. Michelangelo does not portray landscapes, vegetation, or animal life; there are hardly any objects to distract us from the people. Michelangelo was entranced by the body—its musculature, its skeletal structure, its twistings and turnings, its living flesh. This is most striking in his Last Judgment, an obscene explosion of naked bodies.

The Catholic Church has traditionally had a fraught relationship with the human body, to say the least; but Michelangelo seems not to have shared this aversion. If you believe that humanity was made in God’s image, his fascination for the human form is sensible: by studying the human, you might get a glimpse of the divine.

I end this section feeling much as I did when I walked out of that room: overwhelmed. What are you supposed to say when face to face with such a work of art? How are you supposed to feel? How can you even understand what you are seeing, much less properly appreciate it? Can you, through any means, do justice to the experience? Michelangelo’s frescos are, for me, like Shakespeare’s Hamlet or Beethoven’s final symphony: a work that reduces me to the same stunned speechlessness as the starry sky.

St. Peter’s Basilica

By the time I left the Vatican museum—winding my way down the double-helix staircase—I was hungry, thirsty, and totally dazed. I bought an overpriced coca-cola from a vending machine, gulped it down, and then bought a bottle of water. Soon I was out on the street again. I had just seen some of the greatest art in the world; but every trace of aesthetic pleasure vanished in the hot sun.

I wanted to go home and sleep, but I didn’t have time to waste. I still had to go see the Vatican’s Basilica.

San Pietro in Vaticano is the church at the very center of the Catholic world. It is the last of the four major basilicas (I’ve written about the other three here), and the most important. The building, as it appears today, is actually the second St. Peter’s Basilica; the first was built during the time of Constantine, and had fallen into such disrepair during the Avignon Papacy that it was clear repairs were needed. The infinitely ambitious Pope Julius II—the ever-present specter of this post—was not content with mere repairs, however, and conceived a project far more daring: to tear down the original St. Peter’s and rebuild it on an even grander scale.

If you bear in mind that the original church was one of the most venerable, most historical, and most important churches in Europe, not to mention one of the biggest, you can get a notion of how bold this plan really was. Julian wanted not only to rival, but to surpass the great ruins of Rome that still towered above everything else in the city.

A contest was held for designs of the new building, and Donato Bramante’s design was the winner; he called for a Greek cross and a massive dome, modeled after the Parthenon’s. One hundred years earlier, the architect Brunelleschi had designed the massive dome the cathedral of Florence, still the biggest brick dome in the world, and Bramante wanted to build something even bigger. But construction was slow in getting off the ground; and it was not long before both Bramante and Pope Julius died. The leadership eventually passed to Raphael, who altered the design to include three main apses; but Raphael died, too, and the project changed hands many times again. When Charles V’s troops sacked Rome, in 1527, this did not help matters. Eventually Michelangelo, then an old man, begrudgingly took on the job; and nowadays his contributions are regarded as the most important.

The Basilica sits at the end of St. Peter’s square. This is a massive plaza, closed to vehicles, that is enclosed by two sprawling colonnades that welcome the visitor in a gigantic embrace. The square was designed by Bernini during the 17th century, and is visibly a product of the Counter-Reformation: grand, impressive, and crushingly huge. The colonnade is four columns deep, and is topped by a row of statues that are difficult to identity from the ground. In the center of the plaza is an obelisk, originally taken from Egypt during the reign of Augustus (a visible marker of the continuity between the Roman Empire and the Roman Church).

On any given day, the plaza is probably one of the most diverse places on earth. Visitors from hundreds of countries, sporting clothes of every imaginable style, speaking a befuddling mix of languages, crowd the massive square. The one thing they all have in common—at least on a sunny, summer day—is that they are very sweaty, and are busy taking photographs.

I was certainly sweaty when I got on the line to enter the Basilica. To pass from the plaza to the Basilica, you need first to go through security: this means waiting in line for the metal detectors. After you pass through security, however, you can waltz right inside. The Basilica is free to visit, which means that you can still see one of the great works of Renaissance architecture even if you forget to buy tickets for the Vatican Museums.

When you walk into St. Peter’s, the first and most persistent impression is the sense of space—open space, empty space, expanding space flooded with light. Everything is on such a huge scale that it is difficult to keep it in perspective; the ceiling is far above you, but sometimes does not appear so high up because everything is proportionally large; and it is only when you compare the little men and women scurrying about on the floor that you realize how big is everything.

The next impression, for me, was an overpowering sense of splendor and fine taste. As in so many Italian churches, but on an even more magnificent scale, the decoration of every surface is lush: shiny, colorful, and finely textured. Statues adorn nooks and crannies—heroic statues of popes and saints—each of them of the highest quality; and yet there are so many, and each is so consistently masterful, that no single thing particularly attracts your attention. Instead, all of the decoration and the statues create an atmosphere of awe.

Seeing the dome of St. Peter’s from the inside is somewhat surreal. It is so big, and so far away, that it is difficult to gauge exactly how big and how far away it is, exactly. Underneath the dome is one of the most famous works in the Basilica, Bernini’s Baldachin. This is a canopy, somewhat like a pavilion, that sits above the main altar. And it is gigantic: stretching to 30 meters (98 feet) in height, it is the largest bronze object in the world. (And despite this, it still looks tiny in the massive space of the Basilica.) The most distinctive and, for me, the most attractive feature of the work are the twisting, swirling columns that support it.

After wandering my way through the Basilica for a while—open-mouthed, exhausted, too dumbstruck and tired to really process any of the experience—I turned to leave. But there, on the way to the exit, was the most famous artwork of all: Michelangelo’s Pietá. The statue now sits in a side-chapel near the front portal, protected by a shield of bulletproof glass. (This glass was not always there. In 1972, a mentally disturbed Australian geologist attacked the statue with a geological hammer, while shouting “I am Jesus Christ!” He managed to destroy Mary’s arm and nose, and it was only through painstaking reconstruction that the statue was restored to its previous appearance. The world is an odd place.)

The statue is extraordinary. Jesus lays sprawled on Mary’s lap, while she looks down at his lifeless body. Jesus’s face is impossible to see clearly, since it is turned limply toward the sky; but Mary’s face is fully visible. For a woman old enough to have an adult son, she is strikingly youthful and beautiful. Her expression is a masterpiece: so quietly sad, so mournful, and yet not despairing; a tranquil and meditative grief. The viewer cannot help but recall all the images of the Virgin with the Christ Child, rosy-cheeked and smiling, sitting on her lap; now Christ still sits on her lap, a grown man, gaunt, tortured, and put to death. The mother gave life to the son, and now he is gone; but the son will return, and he will give life to mankind. Death and life are united in one image—the tragedy of mortality and the injustice of the world, and the hope of immortality and the justice of the universe.

I stood there for a long while, admiring the statue, and then turned to go. There was only one thing I had left to see: the crypt. St. Peter’s contains the remains of over 100 people, most of them Popes. This crypt is free to visit. To get there, I walked around the side of the building and then down a staircase.

What surprised me, most of all, was its plainness. The walls are white and mostly devoid of decoration; the tombs are relatively simple—at least, compared to everything else I had seen that day. If memory serves, many of the tombs had little plaques near them, explaining who the Pope was and what were his most notable accomplishments. I paused to read some of these, but I find that I normally do not remember much when I do this, so I skipped most. (In retrospect, I was right: I do not remember anything I read.)

At the end of the crypt I came to one far more ornate than the rest. It was not a sarcophagus, but a whole shrine—filled with gold and marble—visible through a glass window. I noticed many people pausing, crossing themselves, and praying before the tomb. Who was he? Then I realized: it was the tomb of St. Peter himself.

According to the story, St. Peter was crucified here on Vatican Hill, during the reign of Nero. He was crucified head downward, at his own request, so as not to die in the same manner as his savior. Peter is traditionally regarded as the first Pope, largely because of this passage from the Gospel of St. Matthew (16.18-19): “I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hell will not overcome it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven.” It was for this reason that Constantine decided to build the original St. Peter’s in this spot.

In the 20th century, archaeologists investigated the area underneath the Basilica’s main altar—right underneath Bernini’s Baldachin. Several burials, tombs, and bones have been discovered under the Basilica. It seems that the area had been used as a gravesite before even the Christian era; coins and even animal bones were discovered. In 1968 it was finally announced that the bones of St. Peter’s had been identified. How any bones could be confidently attributed to St. Peter is another question; what matters, I suppose, is that they were given the official sanction, which makes them officially St. Peter’s bones.

Whenever I visit a cemetery, a tomb, or a graveyard, I think about human finitude. Our bodies are so frail, and will inevitably fail one day. Death comes for us all. And when I see these big stone structures we build for our bodies, it seems as if they are attempts to cope with this finitude. Maybe I will die, but my tomb will survive, and my name will be known, and my memory will live on. But this form of immortality is sterile. What is a tomb but a pile of rock? What is a name but a puff of air? What is a memory but a vague light flitting in darkness?

But when I see Laocoön and His Sons, The School of Athens, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and St. Peter’s Basilica, it gives me pause. So much imagination, effort, will, knowledge, and force is compressed into these things that they seem as if they cannot die. This is fanciful thinking, of course. Everything can die, and everything will. But how could anything so splendid be undone, even by destruction? These works seem to transcend their earthly matter and break into the realm of pure forms, immaterial and everlasting. Why I feel this way, and why I choose to express myself using metaphysics and metaphors, I cannot quite say. What I can say is that these works of art do give me a certain feeling of faith: a faith in the human spirit.