New Art of Cookery: A Spanish Friar’s Kitchen Notebook by Juan Altamiras by Vicky Hayward

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I did not expect to be going to a book event during my last weekend in Madrid. But when I learned that an author was going to be talking about a historic Spanish cookbook at my favorite bookstore in the city, I decided that I had to make time for it.

I was transfixed from the start. The history of food is, I think, often overlooked—even by history buffs; and yet it provides a fascinating lens through which to learn about the past. In daily life, we are often apt to think of traditional dishes as things that have existed since time immemorial. But this often isn’t the case. In this cookbook, originally published in 1745, you will not find potato omelette, or paella, or croquetas, or cocido, or gazpacho…

Wait, I’m getting ahead of myself. Let me describe what this book is, first. Nuevo arte de la cocina is a cookbook published under the name Juan de Altamiras (a pseudonym) in 1745. It proved to be immensely popular, remaining a bestseller well into the next century. The book’s author—whose real name was Raimundo Gómez—was a Franciscan friar, who grew up and spent much of his life in rural Aragón. This book is a contextualized translation by the English author Vicky Hayward. Throughout the book, she adds a great deal of fascinating historical context, as well as modernized versions of each of the over 200 recipes here.

As you might expect, the book is organized along religious lines, with food for meatless and meat days. Back then, something like a third of the year consisted of meatless days; and during Lent, the pious were supposed to be basically vegan. This makes the book a surprisingly good resource for vegetarian cooking. Yet what made it so innovative in its time was that, unlike so many previous cookbooks, Altamiras wrote for ordinary Spaniards—not courtly chefs. The recipes here are simple home cooking at its finest, requiring basic ingredients and straightforward technique. This was revolutionary at the time.

And to return to my previous point, much of the cooking can seem surprisingly exotic. Altamiras uses sauces made from hazlenuts, almond milk, and pomegranate juice. He mixes citrus, saffron, and tomato, and loves to add cloves and cinnamon to his savory dishes. Hayward was good enough to cook samples for the audience at the book event—several of which made me think of Iranian food. According to Hayward, this is because the Morisco influence (Muslims who had converted to Christianity in the 15th century) was still alive and well in Altamiras’s childhood.

I was also surprised at the wealth of ingredients available to Altamiras. He calls on a wide range of fruits and vegetables, as well as fresh fish—despite not living near the coast. He had eggs aplenty and endless ham and lamb, not to mention nuts, legumes, and spices. Saffron grew locally in his day, and salt cod was a staple (though including such a humble ingredient as salt cod was innovative). Most surprising of all, he made iced lemon slushies by using the snow in the nearby mountains. This was a rich and varied diet.

Hayward has fascinating things to say about all of this—the cooking techniques, the sources for ingredients, the role of religion, the Muslims influence, and so much more. More than so many other history books, this one made me feel transported back in time. And a delicious time it was.

Now, one would think that there could be nothing more innocuous than a translation of an 18th century Spanish cookbook. And yet, the event I went to last month was the first event held in honor of the book—eight years after its initial publication! According to Hayward, this is because her book attracted the ire of the Aragonese government, who were offended that a foreigner had beaten them to the punch in bringing their native son to a wider audience. She reports being attacked left and right by Spanish academics. If this is true, it is very silly.

I left the event in a buoyant mood, glad that I could still be so surprised by Spanish history after so many years. And I celebrated, appropriately, by the orgy of food that is Tapapiés—Madrid’s annual tapa festival, held in the Lavapiés neighborhood. It was a wonderful way to spend my last Friday in the city.

View all my reviews

Category: Practical

Review: Bird by Bird

Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

There is a peculiar pleasure in reading books about writing. It is the only craft in which the manual to do it is an example of the craft itself. And since writers tend to be on the eloquent side, they are very good at making their particular pursuit sound interesting and admirable and arduous. Have you heard musicians talk about music? Poor fellows. Either they use the jargon of theory, or are reduced to the blandest platitudes.

Nevertheless, while writers may be in an excellent position to beautify and dramatize their profession, they are in a poor position to teach it. Writing simply cannot be broken down in the way that music can, into notes, scales, chords, etc. You cannot sit down and practice writing by typing the alphabet. Indeed, anyone who tries to teach writing in any capacity will quickly find that it involves so many subtle skills—from basic grammar, to the conventions of spelling and punctuation, to literary sensibility and aesthetic taste—that it resists being broken down into a set of teachable skills. Either it’s all working together, or it’s not.

Lamott begins on solid ground, by reiterating the advice given to all aspiring writers. Start small, write what you know, chuck perfectionism, give yourself permission to write bad first drafts. Nobody pretends that this advice is original, but it bears repeating, and often, since writers for some reason seem particularly prone to crippling self-doubt. I suppose it’s because writing, unlike playing guitar or painting a watercolor, is not particularly fun in itself. There is no sensory or physical feeling to enjoy. And writing being such a solitary pursuit, there is not even a social element. It is just you and the content of your words, and it can be a lot to bear.

Yet Lamott adds quite a bit to this basic, timeworn advice; and unfortunately for me, much of it rubbed me the wrong way. The rest of this review will thus seem unduly negative. So before I move on, I should say that any book that encourages people to read or to write is, for me, a good book. And this one has done a lot of encouraging.

The quickest way I can summarize what I felt was lacking in Lamott’s book is this: she does not pay enough attention to aesthetics. Put another way, I think her approach to writing is overly confessional. Lamott is concerned, above all, with expressing truth—not scientific truth, but personal, emotional, or even spiritual truth. There are times when this approach can be powerful. There are others when it can be horrifically boring.

Here is what I mean. She advises writers to carry around index cards and write down passing thoughts or overheard remarks. She encourages her students to write about their childhoods and to use their traumas. She gives careful advice about how to avoid libel by changing key details about the people in your life you intend to write about. Every story she tells about writing one of her books starts with an experience in her life that she wants to turn into fiction. And this book is peppered—“littered” is perhaps a better word—with anecdotes from her own life.

This is a recipe for thinly veiled autobiographical fiction (which seems to be the exact kind of fiction she herself writes). And the risk of writing such fiction is that it can easily become self-indulgent. It does not take an extraordinary narcissist to overestimate how interesting her life is to others. Most of us already torture our friends with long, boring stories about our days. Let’s not torture our readers the same way.

Of course, our experiences must inform our writing; and of course, most writers do want to express the truth as they see it. But what makes writing pleasurable and memorable, for me, is not that it tells the unvarnished truth about our various traumas, but that it transforms our experience into, well, literature. And this requires just the skills that Lamott neglects in this book.

For example, her chapter on plot counsels the writer to base the story on what her characters would plausibly do next. This strikes me as highly incomplete advice. Though some aspects of a story do grow organically from a character’s personality, most of the famous plots I know have a larger structural integrity. From the white whale to the ghost of Hamlet’s father, stories often contain elements that propel their characters into new situations, rather than vice versa. In the best stories, I think, a perfect balance is achieved between external events and internal turmoil. Thus the Greek tragedies.

This is a quibble, I suppose. More glaring is a complete absence of even a mention of different genres. One would never suspect, from reading this, that there are writers who wish to set their stories in the future or the past, in outer space or a fantastical dimension. One would also not suspect that many writers, rather than taking their inspiration directly from lived experience, are responding mainly to other books. Borges comes to mind as an obvious example, but I think most successful writers do their work in conversation with other authors, living or dead.

A good novel, after all, is not good because it captures something the author felt or thought or lived through. One can read all of Henry James’s books and learn very little about the man. The same can be said for authors as diverse as Shakespeare and Agatha Christie. A novel, once born, should stand on its own, and not serve as a window into the life of its author. This is what separates literature from confession.

Perhaps the most telling thing I can say about this book is that it reads more like a spiritual self-help book than a writing guide. And considering that Lamott seems to have achieved far more success with her series of spiritual self-help guides (she’s a proud Christian) than her fiction, this should perhaps come as no surprise. Indeed, I found this book most moving and powerful when she discussed how writing has helped her get through hard times. It may not be great advice for a novel, but it is not bad advice as far as life is concerned.

View all my reviews

Review: How to Draw

Drawing was one of my first obsessions. Not that I was ever any good at it. I had very little interest or ability in the visual arts; rather, I used drawing as a way to channel my other young obsessions. These ranged from whales, to dinosaurs, to guns, to cars, to phantasy battles—all of which I drew in a kind of careful, painstaking schematic style, wholly two-dimensional, like a crude blue-print. Eventually, my interest shifted to music and reading, and drawing was left behind.

My interest in this childhood preoccupation was reignited by reading Leonardo da Vinci and Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Both of these men used the pencil as a way of examining the world, of almost literally pulling it apart (both of them performed dissections, too), and of thinking about structure and form in ways no one had before. In short, for both the Renaissance painter and the Spanish neuroscientist, drawing was a philosophy and a science in addition to being an art, and this piqued my curiosity. Besides, I had always wondered if I could finally learn to draw in three-dimensions.

This set of lectures by David Brody was an excellent resource in this goal. Brody covers all of the basic techniques of drawing—line, composition, value, color, perspective, and the human form—including exercises, analysis, and history along with his demonstrations. To really work through all of these lectures would take a great deal of time. I spent over a year, on and off (mostly off), with these lectures, and even so I think far more time would be required to achieve results comparable to his (intimidatingly amazing) students.

On the whole, I would rate these lectures very highly. Brody takes an academic approach, trying to get his students to think analytically and to apply general-purpose techniques to a wide range of problems. That is, rather than focusing on specific tricks—such as how to draw convincing eyes or a tree—Brody tries to boil down drawing into fundamental techniques and approaches. Granted, I do think Brody took this approach too far, as a few lectures consist almost entirely of abstract discussions of visual space, hierarchy, color, and so forth. I think the series would have been improved with more draw-along types of activities.

Brody himself comes across as intelligent and surprisingly erudite. He uses many historical examples in his lectures—including many from Asia, which was a nice touch. (Brody is also, as it happens, a talented musician who published a popular fake book for the fiddle.) But he is, unfortunately, a rather dry and uncharismatic lecturer, which is one reason why it took me so long to get through this series.

Yet I cannot really complain, since Brody finally helped me to understand perspective, and to finally draw images in three dimensions. (I still need to work on bodies and faces.) And though I entertain few illusions about my own talent as an artist, I do think I developed a better artistic eye. And this is a reward in itself.

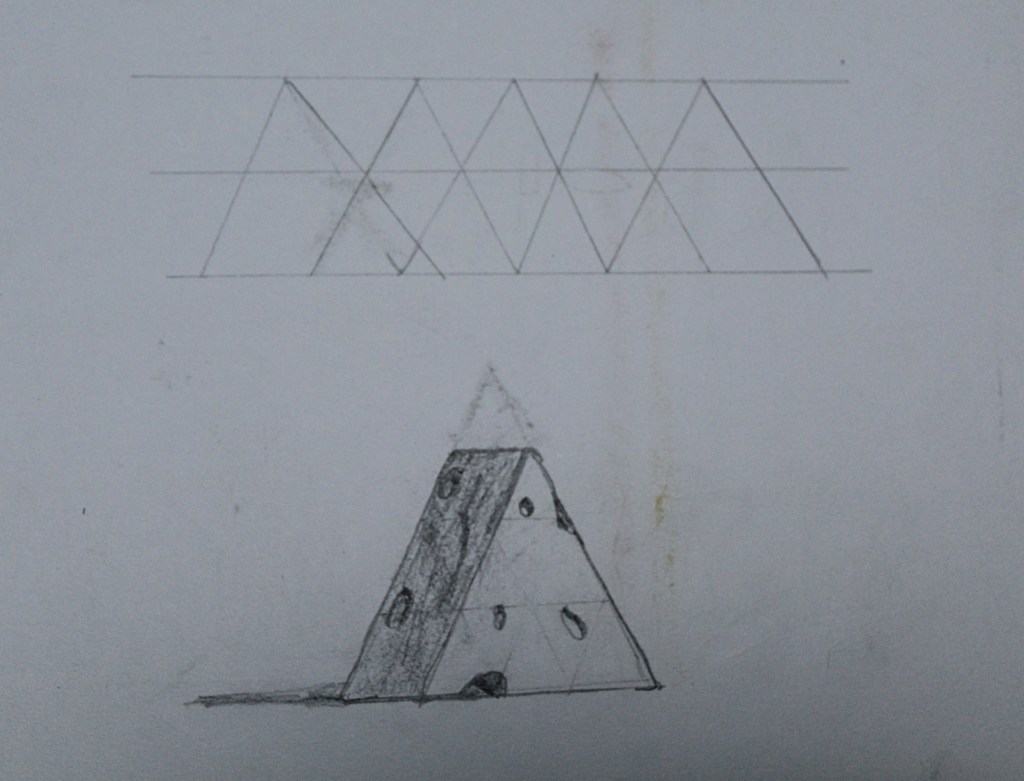

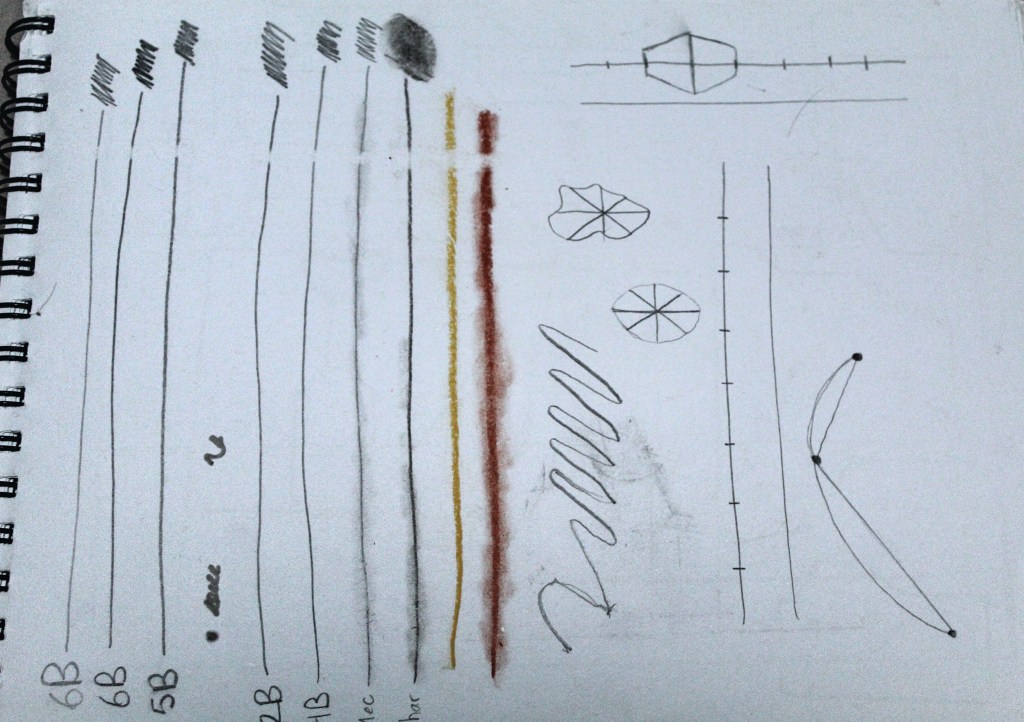

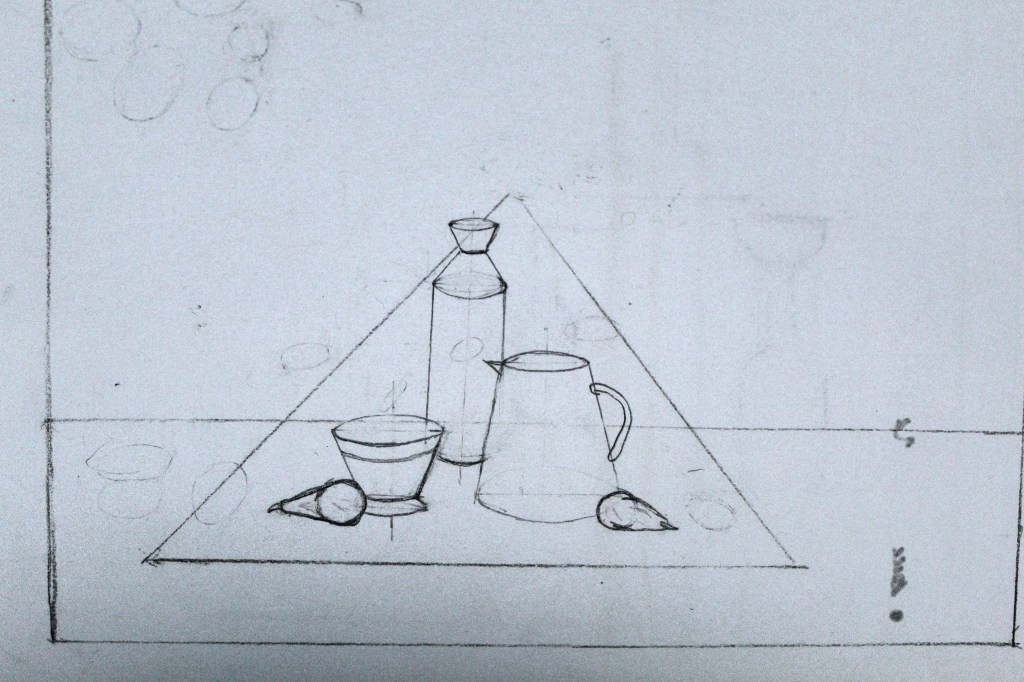

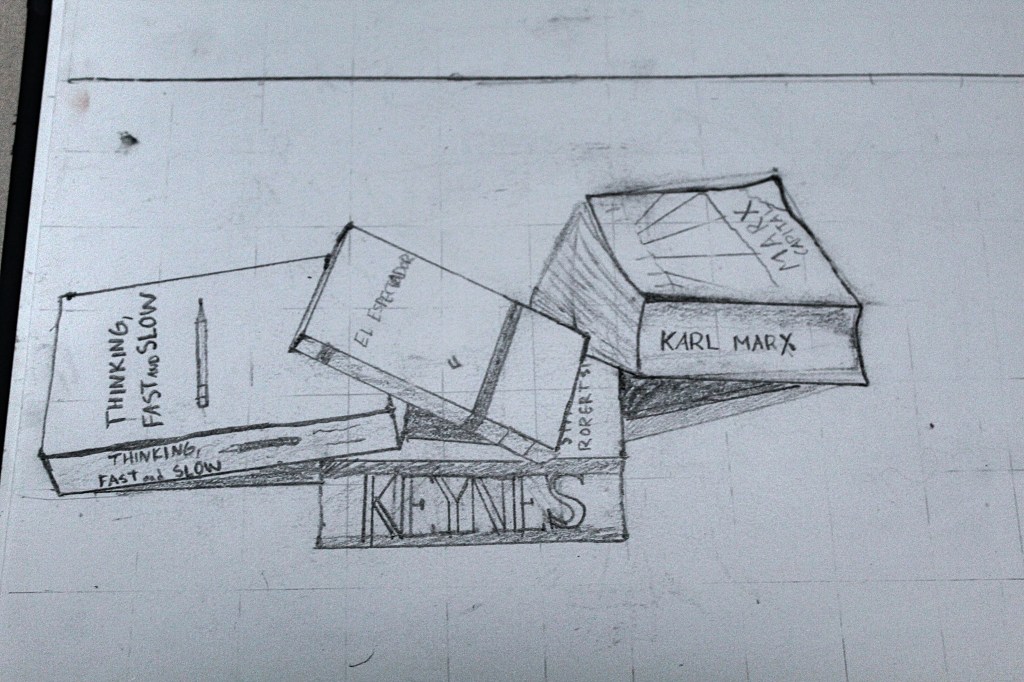

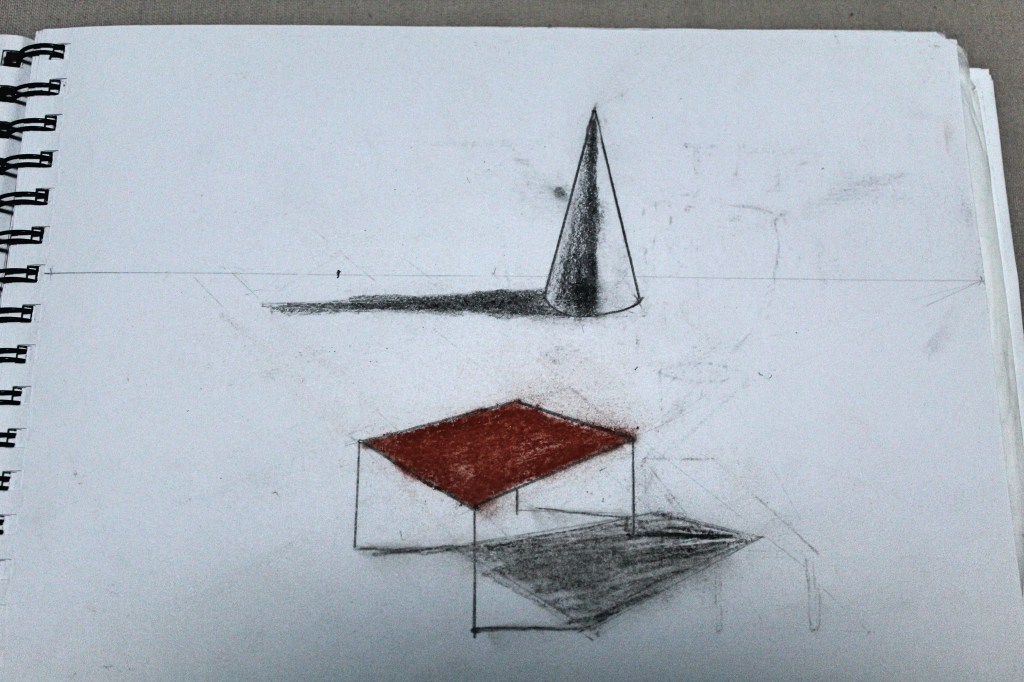

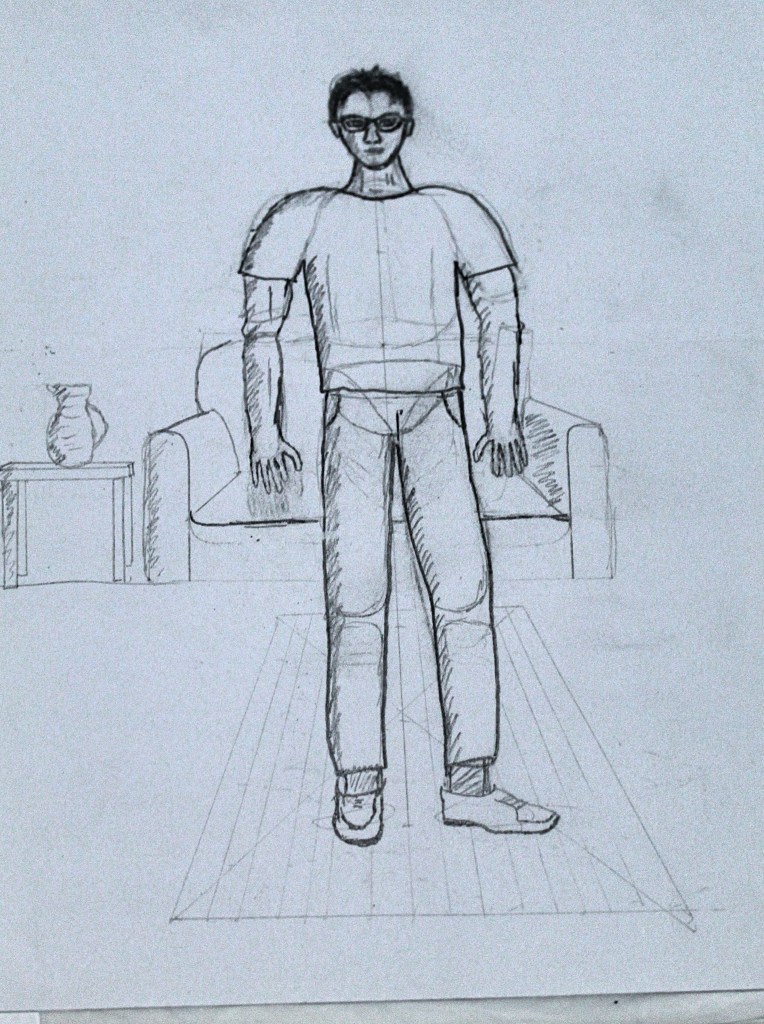

Below I have added some photos of the exercises, not because I am proud of them, but because it gives some idea of what one does in this course:

Review: The Incomplete Book of Running

The Incomplete Book of Running by Peter Sagal

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Of all the people on the face of this green earth, I never thought I would be the one reviewing this book. Indeed, I began this year by writing a blog post about my new year’s resolutions, confidently predicting that, whatever happened, I would not begin to exercise. Yet a month later I found myself in a sportswear store, perplexedly looking at running gear. What happened?

Nothing, really. Unlike Peter Sagal, my foray into running has not been the product of any personal troubles or existential crises. I am 27, too old for my quarter-life crisis, too young to be worried about entering middle age. I haven’t gotten married yet, and so have not had to endure any difficult divorce. I haven’t even had a bad breakup recently. I just decided to try something new, out of a sense of curiosity.

When I was in high school, you see, I dreaded the day when we were made to run a mile in gym class. It seemed like such an impossibly long distance. I was chubby and out of shape, so I could never make it the whole way without walking a considerable portion. Later on, at the ripe age of 17, I had to go to physical therapy for my knees after overstretching in Tae Kwon Do classes. These experiences convinced me that running was not my bent. But last February, feeling experimental, I decided to see whether walking a lot in Europe had inadvertently made me capable, finally, of running a mile without stopping. And it had.

Judging from this book, my experience was not typical. Running seems to be one of those hobbies, like meditation or prayer, that people pick up after some sort of acute trauma. Sagal got into running as he entered his forties, facing a midlife crisis which was to include a difficult divorce. As a comparison, it took the Buddhist author, Pema Chödrön, two divorces to become a celibate nun and celebrated teacher. (Lacking this experience, I am neither particularly enlightened nor especially fast.) Indeed, Sagal’s divorce haunts these pages as a kind of bitter undercurrent which seems to put many readers off. For my part, I do not require radio comedians to write about their ex-wives with saintliness.

I doubt I would have enjoyed this book half as much if I had bought the print version. Sagal is a radio personality, and the audiobook has his skillful delivery and signature voice. Using the audiobook also means that you can listen to the book while running. This is what I did, pledging that I would get through the book’s five hours and twenty-five minutes in five runs or fewer—and I succeeded. Listening to bald man who has struggled with his weight, and who had little natural talent to begin with, was great motivation as I shuffled my own soft body through Madrid’s Retiro Park. Now, here is an athlete I can identify with.

Apart from recounting some of his marathon experiences—which included the 2013 Boston Marathon, where he witnessed the bombing—as well as a few other running anecdotes, Sagal offers a bit of advice—all of it very sensible, and most of which I do not follow: don’t over-train, run with a group, eat healthy, etc. Most interesting to me was Sagal’s advising runners to go without headphones, in order to experience their environment and to mindfully monitor their bodies.

In fact, the way that Sagal describes running often reminded me of meditation books I have read. Both practices involve spending a considerable amount of time alone, paying attention to one’s breath and one’s body. Both practices are supposed to relieve stress and make one generally happier. And, as I mentioned, people tend to turn to these practices when they are having a problem. It is curious that focusing on the body can have such strong therapeutic effects.

One major difference between running and meditation is competitiveness. Runners are relentlessly challenging each other and themselves. This may not be wise, but it is fun on occasion. This foolhardy spirit of competitiveness has led me to sign up for Madrid’s half marathon on April 27. If you are standing near the finish line that day, and you wait long enough, you may see a tall, sweaty, teetering American stumble across the finish line. Wish me luck.

View all my reviews

Review: The Art of Worldly Wisdom

Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia by Baltasar Gracián

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Cada uno habla del objeto según su afecto.

This little book is one of the most read and translated works of the Spanish Golden Age. It has been surprisingly influential. Schopenhauer was a famous devotee, and even learned Spanish so that he could produce a translation (which went on to commercial success). Two English translations have been best-sellers, the first in 1892 and the second in 1992. Advice typically does not age well, but Gracián’s has stood the temporal test.

Yet for the reader of the original Spanish—especially the non-native reader—the book can be perplexing. Gracián was a major writer in the conceptismo movement: a literary style in which a maximum of meaning was compressed into a minimum of words, using every rhetorical trick of the trivium to achieve a style that seems to curl itself into a ball and then to explode in all directions. This can make the experience of reading Gracián quite akin to that of reading poetry—except here, unlike in poetry, you can be sure that there is a sensible meaning laying concealed underneath. When the antiquity of Gracián’s Castilian is added to the mix, the result is literary dish that is difficult to digest.

After a meaning is beaten out of Gracián’s twisted words, however, the result is some surprisingly straightforward advice. “Prudent” is the operative word, for Gracián manages to be idealistic and realistic at once, walking the fine like between cynicism and naïveté. Admittedly, however, the bulk of this advice is directed towards the successful courtier, and so is difficult to apply to less exalted positions. There is, for example, much advice concerned with how to treat inferiors and superiors, but in a world where explicit hierarchies are increasingly frowned upon (or at least tactfully concealed), the poor reader wonders what to make of it.

But much of the advice is timeless and universal. Make friends with those you can learn from (but not those who can outshine you!). Don’t let wishful thinking lead you into unrealistic hopes. Never lose your self-respect. The wise man gains more from his enemies than the fool from his friends. Know how to forget. Know how to ask. Look within… As any reader of Don Quixote knows, Spanish is a language exceedingly rich in proverbs; so it perhaps should come as no surprise that this language—so rhythmic and so easy to make rhymes with—is also an excellent vehicle for maxims. Gracián exploits the proverbial potential of Castilian to the maximum, expressing a sly but respectable philosophy in 300 pithy paragraphs.

Despite all the wit and wisdom to be found in these pages, however, I found myself wishing for amplification. Montaigne, though short on practical advice, is long on examples; so by the end of his essays the reader has a good idea how to put his ideas into practice. Gracián, by contrast, has no time for examples, and so the reader is left with a rather abstract imperative to work with. Needless to say I will not become a successful courtier anytime soon.

View all my reviews

Review: The Feeling Good Handbook

The Feeling Good Handbook by David D. Burns

The Feeling Good Handbook by David D. Burns

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Unlike with previous Burns books, I read this one while I was feeling relatively normal and untroubled. I did this because I sensed myself relapsing. Cognitive therapy, as you might know, is based on the premise that your thoughts control your moods and emotions. Thus it works by changing your beliefs and even your values in order to alleviate depression, anxiety, and problems with relationships. In my own experience, this can have a remarkably liberating effect. The problem is that, when the relief passes and you once more get sucked into the humdrum world of daily troubles, the original beliefs and values come creeping back.

But why is this? Why are we so prone to adopting irrational and self-defeating patterns of thought? Why do we embrace unrealistic standards, make unjustified assumptions, jump to unwarranted conclusions—only to wallow in misery and fear and loneliness—when a few pen-and-paper exercises is sometimes all we need to feel better? It is peculiar. Robert Wright argues that our cognitive imperfections stem from our evolutionary heritage. A competitive and materialistic culture might also contribute. Burns, for his part, does not offer much in the way of explanation; his aim is therapy, not theory. Yet answering this question seems vital if we are to fight an offensive battle rather than a defensive one.

It seems to me that the most proactive strategy would be to intervene on the social rather than the psychological realm (if that were possible). To pick a simple example, if an obsession with being the best is really self-defeating—at least as far as happiness is concerned—then why the opposite message so passionately embraced in the culture at large?

Perhaps it is because these value systems, which equate happiness with accomplishment, do benefit the group even if they are not psychologically desirable. An office full of perfectionistic over-achievers might out-compete an office full of contented workers with nothing to prove. Advertisements may not have much effect in a world of high self-esteem. And political parties will have trouble getting elected in a world without anxiety. In these and a thousand other ways, society depends on the very thoughts and attitudes that books like this try to combat. No wonder that relapse is common once therapy ceases.

It is also true that there are hidden, and sometimes ugly, benefits to our bad habits. It feels satisfying to think oneself superior to others. Insulting and controlling other people brings a rush. Anxiety helps us to avoid discomfort. Intimacy requires painful vulnerability. And who wants to accept imperfections in oneself? Burns’ methods require that we see ourselves as flawed, that we acknowledge that other people have a point, that our anger is often unjustified, that we face our fears—and who wants to do that? Indeed, sometimes the beliefs that are most precious to us, the beliefs that form our identity and reality, are just what cognitive therapy encourages us to give up—the belief that, for example, your money makes you superior, or that life is rotten, or that your wife is crazy—and these beliefs can seem more important than happiness itself.

Well, I’m not sure I have a solution to this, other than meditating and occasionally dipping into some cognitive therapy books when I feel particularly troubled. For that purpose The Feeling Good Handbook is well suited, since it is a sort of omnibus of Burns’ general approach, with sections on depression, anxiety, and communication. Even though I was not looking for any special relief, I still found the book useful (specifically the section on procrastination, which prompted me to finally begin submitting my novel to agents). As usual, Burns is a heartening voice—compassionate, intelligent, and motivating—who is accessible without descending into tackiness. And it is always a relief to read his anecdotes, since they remind me that these problems, far from hopeless or strange, are part of the human condition.

Review: Draft No. 4

Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process by John McPhee

Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process by John McPhee

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I include what interests me and exclude what doesn’t interest me. That may be a crude tool but it’s the only one I have.

I came to this book from an odd angle. Neither a reader of The New Yorker (where McPhee has published the lion’s share of his work), nor a reader of John McPhee’s books, nor even aware of his existence until a few months ago, I was nonetheless gifted this book for Christmas. It was an intelligent choice. McPhee is a kindred spirit, a nonfiction writer who loves nature, science, and the written word; whose rapacious curiosity for apparently prosaic subjects—oranges, rocks, the merchant marine—is only matched by his rapacious attention to the craft of writing.

Among a certain crowd of readers and writers McPhee is worshipped this side of idolatry. In this way he strongly resembles another writer for The New Yorker, E.B. White, whose style has become synonymous with good taste. The two men, very unlike in many ways, share something more: an odd mixture of down-home folksiness and slick sophistication. Their tone is frank and unpretentious, their subjects far removed from the shibboleths of high culture, and yet their writing is polished, refined, and consummate.

This book is presented as the written version of McPhee’s famous class on creative nonfiction at Princeton, which he has been teaching for over 40 years. This class is a part of the McPhee legend, since so many of its students went on to become highly regarded writers themselves. (There does seem to be a problem of cause-and-effect in attributing this success to the class, however, since to join the class you need to submit a writing sample, and only the best 16 are admitted.) As such, I opened this book expecting to find something like a style manual or a writing guide.

But Draft No. 4 is only peripherally concerned with giving advice. It is primarily a series of essays on his experience writing, researching, editing, fact-checking, and publishing. I admit that I was disappointed with this at first, since I was hoping for a focused series of tips and exercises, something along the lines of William Zinsser’s On Writing Well; but McPhee writes so charmingly that these misgivings were soon forgotten. Indeed, I had trouble putting the book down, and in short order finished it.

The most memorable chapter of the book is “Structure,” in which he illustrates some of the organizational schemes he has employed. McPhee, you see, is deeply concerned with the structure of his writing, in ways that I didn’t even imagine possible. In writing I tend to think of structure linearly, as an unbroken arc of meaning; but McPhee has the mind of a modern architect, and his arrangements are far more intricate. He illustrates these arrangements with idiosyncratic diagrams—incomprehensible to all but him. The diagram for Encounters with the Archdruid, for example, consists of the letters A, B, and C over a line, with D underneath. What does this mean?

In the rest of the book we are given several snapshots of his career. We see him interviewing Woody Allen (“a latent heterosexual”), learning to use Kedit (an arcane software program that he uses to organize his material), inventing bad puns as a young writer for Time, working with (and sometimes against) The New Yorker’s famously assiduous fact-checking department, negotiating the perils of editors, house-styles, and publishing deals, and other adventures in the life of a nonfiction writer.

The writing advice interspersed between these anecdotes, collected together, would likely not amount to a page and a half. And I must say the advice did not grab me. After long enough, all council on the craft of writing begins to sound the same: omit, condense, search for the right word, start with a strong lead, etc., etc. John McPhee’s emotional guidance is also in line with a noble tradition: writing is herculean, writers are masochists, writer’s block is the seventh layer of hell, and so on. Parenthetically, I think writers ought to stop complaining about writing or wallowing in its struggles. To me it always comes across as shamelessly melodramatic.

All carping aside, I thoroughly enjoyed this book. McPhee has clearly earned his reputation as a master of the craft. Each line of every essay exhibits intelligence, taste, and care. He is full of stories and knows how to tell them; and, true to form, he knows how to weave these stories into a satisfying whole. I look forward to reading more of McPhee, particularly Annals of the Former World, and in the meantime will hope that some of his obsessive care for the art of writing has rubbed off.

Review: Cracking the GRE

Cracking the GRE by The Princeton Review

Cracking the GRE by The Princeton Review

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Compared with Europe, America has a strange fixation with standardized tests. Administrators and bureaucrats seems to view these tests as tools of accountability, allowing for standard measurement across the system with no possibility of error. But the result is often quixotic: the attempt to come up with a test that creates a normal curve in scores, a test immune to differences in social and cultural background, and a test that measures something predictive of future success, irrespective of the field or career.

As far as these tests go, the Graduate Record Examinations (GRE) is well done. The math sections only include the most basic techniques, focusing instead on tricky word problems or painstakingly lengthy operations, which theoretically would put all students—regardless of math background—on an equal footing. The essays focus on equally fundamental skills: creating and defending a thesis, and critiquing somebody else’s thesis. The verbal section is a straightforward vocabulary and reading comprehension drill. In sum, as far as possible, I think that the GRE is focused on fundamental skills needed for study.

The catch, of course, is the “as far as possible.” For no matter how much the test-makers try, a physics major and a history major will not be on an even footing in the math and verbal sections. What is more, by making vocabulary such an integral part of the exam, people from more privileged backgrounds—whose well-educated parents work white-collar jobs—have an obvious advantage. This is not to mention the upper hand that the well-off always have in competitions of this sort: the time available for studying (without worrying about multiple jobs or rent), and the resources (private tutors and so on) to prepare adequately.

In any case, can even a well-designed test give valuable information at the graduate school level? For lower-level education, where students are taught the basics of academic skills, a general test seems more plausible. But as students apply to Masters and Doctorate programs—the final steps of vocational and academic specialization—the usefulness of a generalized skill exam is far more questionable. The ability to write an essay in 30 minutes taking a stance on a randomly generated quote (one of the essay tasks) is perhaps hardly related to the ability to, say, write a detailed exploration of the post-Soviet period in Poland.

Granted, I can see why admissions offices like tests such as this one. First, it is a quick and easy to cut down the hefty stack of applications. What’s more, the GRE scores do provide a standard measurement across varying backgrounds (but what is it a measurement of?). And even if the admissions office sees the GRE as purely pro forma—something that is not uncommon—the obstacle of a $205, 4-hour test may help whittle out those less interested in applying.

However convenient it may be for these admissions officers, I personally cannot help being frustrated with exams like this. At present, Educational Testing Services (ETS), its creator, is the Standard Oil of the testing business. To apply to any institution of higher education in the United States, you must pay a toll—in time, stress, and money—to this organization. If I thought that this ritual improved educational quality in any way, I would tolerate it; but I have trouble believing that.

ETS is not the only entity that benefits from this arrangement, since the competition for scores gives rise to innumerable test-prep companies and products, such as this book. I have used the Princeton Review on numerous occasions, and have consistently appreciated their prep-books. This book provides quite a bit of value for the price: including dozens of specific techniques, and 6 full-length practice tests.

Because the Princeton Review can’t use real ETS questions, they must come up with their own. And this is no easy thing, since their questions must replicate exactly the look, difficulty, and type of questions on the real thing. For what it’s worth, in my own experience I have found that the real ETS verbal questions are easier than the Princeton versions, while the ETS math section is more difficult than Princeton’s—though admittedly this difference is fairly small.

A world where we didn’t have to spend months preparing for standard exams would be ideal. But in the world we live in, Princeton Review books are a valuable aid.

Review: How to Win Friends and Influence People

How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie

How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

When dealing with people, let us remember we are not dealing with creatures of logic. We are dealing with creatures of emotion, creatures bristling with prejudices and motivated by pride and vanity.

Dale Carnegie is a quintessentially American type. He is like George F. Babbitt come to life—except considerably smarter. And here he presents us with the Bible for the American secular religion: capitalism with a smile.

In a series of short chapters, Carnegie lays out a philosophy of human interaction. The tenets of this philosophy are very simple. People are selfish, prideful, and sensitive creatures. To get along with people you need to direct your actions towards their egos. To make people like you, compliment them, talk in terms of their wants, make them feel important, smile big, and remember their name. If you want to persuade somebody, don’t argue, and never contradict them; instead, be friendly, emphasize the things you agree on, get them to do most of the talking, and let them take credit for every bright idea.

The most common criticism lodged at this book is that it teaches manipulation, not genuine friendship. Well, I agree that this book doesn’t teach how to achieve genuine intimacy with people. A real friendship requires some self-expression, and self-expression is not part of Carnegie’s system. As another reviewer points out, if you use this mindset to try to get real friends, you’ll end up in highly unsatisfying relationships. Good friends aren’t like difficult customers; they are people you can argue with and vent to, people who you don’t have to impress.

Nevertheless, I think it’s not accurate to say that Carnegie is teaching manipulation. Manipulation is when you get somebody to do something against their own interests; but Carnegie’s whole system is directed towards getting others to see that their self-interest is aligned with yours. This is what I meant by calling him the prophet of “capitalism with a smile,” since his philosophy is built on the notion that, most of the time, people can do business with each other that is mutually beneficial. He never advocates being duplicitous: “Let me repeat: The principles taught in this book will work only when they come from the heart. I am not advocating a bag of tricks. I am talking about a new way of life.”

Maybe what puts people off is his somewhat cynical view of human nature. He sees people as inherently selfish creatures who are obsessed with their own wants; egotists with a fragile sense of self-esteem: “People are not interested in you. They are not interested in me. They are interested in themselves—morning, noon and after dinner.”

Well, maybe it’s just because I am an American, but this conception of human nature feels quite accurate to me. Even the nicest people are absorbed with their own desires, troubles, and opinions. Indeed, the only reason that it’s easy to forget that other people are preoccupied with their own priorities is because we are so preoccupied with our own that it’s hard to imagine anyone thinks otherwise. The other day, for example, I ran into my neighbor, a wonderfully nice woman, who immediately proceeded to unload all her recent troubles on me while scarcely asking me a single question. This isn’t because she is bad or selfish, but because she’s human and wanted a listening ear. I don’t see anything wrong with it.

In any case, I think this book is worth reading just for its historical value. As one of the first and most successful examples of the self-help genre, it is an illuminating document. Already in this book, we have what I call “Self-Help Miracle Stories”—you know, the stories about somebody applying the lessons from this book and achieving a complete life turnaround. Although the author always insists the stories are real, the effect is often comical: “Jim applied this lesson, and his customer was so happy he named his first-born son after him!” “Rebecca impressed her boss so much that he wrote her a check for one million dollars on the spot!” “Frank did such a good job at the meeting that one of his clients bought him a Ferrari, and another one offered him his daughter in marriage!” (These are only slight exaggerations.)

Because of this book’s age, the writing is quaint and charming. Take, for example, this piece of advice on how to get the most out of the book: “Make a lively game out of your learning by offering some friend a dime or a dollar every time he or she catches you violating one of these principles.” A lively game! How utterly delightful.

Probably this book would be far more effective if Carnegie included some exercises instead of focusing on anecdotes. But then again, it would be far less enjoyable reading in that case, since the anecdotes are told with such verve and pep (to quote Babbitt). And I think we could all use a little more pep in our lives.

Review: Tools for Teaching

Tools for Teaching: Discipline, Instruction, Motivation. Primary Prevention of Classroom Discipline Problems by Fredric H. Jones

Tools for Teaching: Discipline, Instruction, Motivation. Primary Prevention of Classroom Discipline Problems by Fredric H. Jones

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Have you ever looked at the work kids turn in these days and wondered, “What will happen to this country in the next 50 years?” When you watch Larry sharpen his pencil, you know that the future is in good hands. It’s inspirational.

Last year I switched from teaching adults to teaching teenagers. Though I’m still teaching English, the job could hardly be more different. With adults, I could focus entirely on content; my students were mature, intelligent, and motivated, so I could think exclusively about what to teach them, and how. With kids, I am dealing with a classroom full of energetic, distracted, unruly, loud, and sometimes obnoxious humans whose main motivation is not to fail the upcoming exam. They’re not there because they want to be, and they would always inevitably rather be doing something else.

This probably makes me sound jaded and disenchanted (and I hasten to add that I actually have a lot more fun teaching kids, and my students are great, I swear!); but the fact is inescapable: when you’re teaching in a school setting, you need to worry about classroom management. Either you will control the kids, or they will control you.

It is the hope of every beginning teacher, myself included, to manage through instruction. We all begin with the same dream: to create lessons so dynamic, so enriching, so brilliant, and to teach with such charisma and compassion, that misbehavior isn’t a problem. But this doesn’t work, for two obvious reasons. For one, we don’t have unlimited control of the curriculum; to the contrary, our room to maneuver is often quite limited. And even with complete autonomy, having interesting lessons would be no guarantee of participation or attention, since it only takes one bored student to disrupt, and only one disruption to derail a lesson.

Even if you’re Socrates, disruptions will happen. When they do, in the absence of any plan, you will end up falling back on your instincts. The problem is that your instincts are probably bad. I know this well, both from experience and observation. Our impulsive reaction is usually to nag, to argue, to preach, to bargain, to threaten, to cajole—in other words, to flap our mouths in futility until we finally get angry, snap, yell, and then repeat the process.

But no amount of nagging creates a motivated classroom; and no amount of speeches—about the value of education, the importance of respect, or the relevance of the lesson to one’s future—will produce interested and engaged students. In short, our instinctual response is inefficient, ineffective, and stressful for both teacher and students. (Again, I know this both from experience and observation.)

Some strategies are therefore needed to keep the kids settled and on task. And since teachers are chronically overworked as it is—the endless grading and planning, not to mention the physical strain of standing in front of classes all day—these strategies must be neither too complex nor too expensive. To the contrary, they must be relatively straightforward to implement, and they must save time in the long run.

This is where Fred Jones comes in. Fred Jones is the Isaac Newton of classroom management. This book is nothing less than a fully worked out strategy for controlling a room full of young people. This system, according to him, is the result of many hundreds of hours of observing effective and ineffective teachers, trying to analyze what the “natural” teachers did right and the “unnatural” teachers wrong, and to put it all together into a system. And it really is systematic: every part fits into every part, interlocking like the gears of a bicycle.

This makes the book somewhat difficult to summarize, since it is not a bag of tricks to add to your repertoire. Indeed, its main limitation—especially for me, since I’m just assistant who goes from class to class—is that his strategies cannot be implemented piecemeal. They work together, or they don’t work. As a pedagogical nomad who merely helps out, I am not really in a position to put this book into practice, so I cannot personally vouch for it.

Despite this, Jones manages to be utterly convincing. The book is so full of anecdotes, insights, and explanations that were immediately familiar that it seemed as if he was spying on my own classrooms. Unlike so many books on education, which offer ringing phrases and high-minded idealism, this book deals with the nitty-gritty reality of being a teacher: the challenges, frustrations, and the stress.

The main challenge of classroom management—the problem that dwarfs all others—is to eliminate talking to neighbors. Kids like to talk, and they will talk: when they’re supposed to be listening, when they should be working, whenever they think they can get away with it. This is only natural. And with the conventional classroom approach—standing in the front and lecturing, snarling whenever the kids in the back are too loud—talking to neighbors is inevitable, since the teacher is physically distant, and the kids have nothing else to do.

Jones begins by suggesting board work: an activity that each student must start at the beginning of class, something handed out or written on the board, to eliminate the usual chaos that attends the beginning of the lesson. He then goes into detail about how the classroom should be arranged: with large avenues to the teacher can quickly move around. Movement is key, because the most important factor that determines goofing off is physical proximity to the teacher. (This seems certainly less true in Spain, where people are more comfortable with limited personal space, but I imagine it’s quite true in the United States.)

This leads to the lesson. Jones advocates a pedagogical approach that only requires the teacher to talk for five minutes or less at a time. Break down the lesson into chunks, using visual aids for easy understanding, and then immediately follow every concept with an activity. When the kids are working, the teacher is to move around the classroom, helping, checking, and managing behavior, while being sure not to spend too much time with the students he calls “helpless handraisers”—the students who inevitably raise their hands and say they don’t understand. (To be clear, he isn’t saying to ignore these students, but to resist the impulse to re-teach the whole lesson with your back turned to the rest of the class.)

This leads to one of the main limitation of Jones’s method: it works better for math and science than for the humanities. I don’t see how literature or history can be broken down into these five-minute chunks without destroying the content altogether. Jones suggests frequent writing exercises, which I certainly approve of, but it is also hard for me to imagine teaching a lesson about the Spanish Reconquest, for example, without a lengthy lecture. Maybe this is just due to lack of imagination on my part.

When it comes to disruptions, Jones’s advice is refreshingly physical. The first challenge is remaining calm. When you’re standing in front of a crowd, and some kids are chuckling in the back, or worse, talking back to you, your adrenaline immediately begins to flow. Your heart races, and you feel a tense anxiety grip your chest, intermediate between panic and rage. Before doing anything, you must calm down. Jones suggests learning how to relax yourself by breathing deeply. You need to be in control of your emotions to respond effectively.

Then, Jones follows this with a long section on body language. The way we hold our bodies signals a lot about our intentions and our resolve. Confidence and timidity are things we all intuitively perceive just from looking at the way someone holds herself. How do you turn around and face the offending students with conviction? How do you signal that you are taking the disruption seriously? And how do you avoid seeming noncommittal or unserious?

One of the most brilliant sections in this book, I thought, was on dealing with backtalk. Backtalk can be anything, but as Jones points out, it usually takes a very limited number of forms. Denial is probably the most common; in Spanish, this translates to “Pero, ¡no he hecho nada!” Then there is blaming; the student points her finger at her neighbor, and says “But, she asked me a question!” And then there is misdirection, when the offending student says, “But, I don’t understand!” as if they were in a busy intellectual debate. I see all these on a daily basis. The classic mistake to make in these situations is to engage the student—to argue, to nag, or to scold, or to take their claim that they “don’t understand” at face value. Be calm, stay quiet, and if they keep talking move towards them. Talking back yourself only puts you on the same level.

The penultimate section of the book deals with what Jones calls Preferred Activity Time, or PAT. This is an academic activity that the students want to do, and will work for. It is not a reward to hold over their heads, or something to punish the students with by taking it away, but something the teacher gives to the class, with the opportunity for them to earn more through good behavior. This acts as an additional incentive system to stay on task and well behaved.

The book ends with a note on what Jones calls “the backup system,” which consists of the official punishments, like suspension and detention, that the school system inflicts on misbehaving kids. As Jones repeatedly says, this backup system has been in place for generations, and yet it has always been ineffective. The same small number of repeat offenders account for the vast majority of these reprimands; obviously it is not an successful deterrent. Sometimes the backup system is unavoidable, however, and he has some wise words on how to use it when needed.

Now, if you’ve been following along so far, you’ll have noticed that this book is behaviorist. Its ideas are based on control, on incentive systems, on input and output. As a model of human behavior, I think behaviorism is far too simplistic to be accurate, and so I’m somewhat uncomfortable thinking of classroom management in this way. Furthermore, there are moments, I admit, when the job of teaching in a public school feels more like working in a prison than the glorious pursuit of knowledge. Your job is to keep the kids in a room, keep them quiet and seated, and to keep them busy—at least, that’s how it feels at times. And Jones’s whole system can perhaps legitimately be accused of perpetuating this incarceration model of education.

But teachers have the choice of working within an imperfect system or not working. The question of the ideal educational model is entirely different from the question this book addresses: how to effectively teach in the current educational paradigm. Jones’s approach is clear-eyed, thorough, intelligent, insightful, and eminently practical, and for that reason I think he has done a great thing. Teaching, after all, is too difficult a job, and too important a job, to do with only idealism and instinct as tools.