It was odd to be back. My last trip to Dublin, in 2017, was in December. Along with one of my childhood friends and his little brother, we wandered around the city in the cold and dark. We did a lot of walking and a lot of drinking, but not a great deal of sight-seeing. Now, nearly six years later, I was here in early September for a family vacation. The weather was warm, the days long, and I could finally see all the great monuments of Dublin.

Oriented around the River Liffey, Dublin is far and away the biggest city in the Republic of Ireland. I find it a difficult place to describe. It is dense and populous, yet it has a strange intimacy. One doesn’t feel, as while visiting Paris or New York, lost amid an endless expanse of streets. On the contrary, I felt that I got my bearings rather quickly. And though there are plenty of historical buildings, Dublin also does not feel particularly old. The city is not romantic or particularly beautiful, nor is it cozy and immediately welcoming. Perhaps the best way I can describe it is that it feels like the setting for a tragic-comic play.

Dublin is fairly spread-out for a European city. Its center—if it has one—is the O’Connell Bridge. This bridge is named in honor of the political leader Daniel O’Connell, whose monument is nearby; he was one of the many people who advocated, protested, and fought for Irish autonomy. Within walking distance is the Ha’Penny Bridge and the Temple Bar nightlife district, as well as Trinity College. Standing on this bridge and facing north, you will likely catch sight of the Spire of Dublin, which is exactly what it sounds like. Standing at 120 meters (390 feet) tall, this huge metal spike is not especially beloved by the local population, who have a variety of nicknames for it—such as the “stiffy on the Liffey.”

Wandering southward from the bridge, you will likely come across the statue of Molly Malone. This rather busty woman is carrying her cart of baskets, presumably holding the “cockles and mussels, alive, alive, oh!” of the folk song. Chances are, a street musician will be set up before this statue of Irish musical womanhood, and it may be worth your while to stop and listen. The live music scene in Dublin is one of its great charms. Further south is St. Stephen’s Green, the loveliest park in a city not particularly rich in greenspace.

I usually prefer using public transportation to get around, though my mom often insisted that we take a taxi. This ended up being a good choice, as the taxi drivers were generally charming and informative. Nevertheless, I did want to pick up a transport card, called a Leap Card. To do this, we went to the General Post Office, on O’Connell Street. This neo-classical structure is something of a national monument, as it was the center of the Easter Rising—a violent revolt against British rule. The building still has bullet holes in its facade to prove it. Nowadays, it is a convenient place to mail letters and get your bus pass.

Yet what I was most excited for was a pair of monuments somewhat outside the city center. After a short bus ride—yes, we had to use those Leap Cards—we found ourselves, somewhat jarringly, standing between a modern office building and an imposing stone structure. (The city is full of juxtaposing old and new.) This fortress-like structure was Kilmainham Gaol, one of the most infamous places in Ireland.

This gaol, or jail, was built in 1796 to replace the medieval dungeon that the city had been using. It was meant to be modern, embodying the “Panopticon” idea of Jeremy Bentham. The idea was to make all of the individual cells visible from a central point, thus subjecting the inmates to constant surveillance. Being under observation, it was hoped, would eventually create self-discipline. Personally, I am doubtful that this really works. In any case, only one part of the prison—the strangely beautiful Main Hall—follows this philosophy. The rest of the prison consists of narrow hallways of cramped cells.

Conditions in the jail were bad. Both men and women were locked up, often on minor charges such as vagrancy or prostitution. Children were even imprisoned here—in one famous case, a child as young as three. Packed like sardines into the cells, the prisoners endured cold, darkness, and hunger. But this is not why the prison became so famous. This was due to its role in the many struggles for independence throughout Ireland’s history. As far back as the 1880s, the great nationalist politician Charles Parnell was imprisoned here (though apparently in quite genteel conditions).

Parnell escaped with his life. Many others were not so lucky. After the aforementioned Easter Rising of 1916 was crushed, its leaders were taken here, court martialed, and executed. Public sympathy for these figures directly contributed to drafting of the 1918 Declaration of Independence by Sinn Féin. During the War of Independence, many anti-British fighters were imprisoned here; and later, during the Irish Civil War, four IRA prisoners were executed in this jail. In short, Kilmainham Gaol has a grim role in Irish history.

Learning about such things is thirsty work. Thankfully, the Guinness Factory is not too far. Now, I’d visited a few breweries, but this was unlike any I had seen before. The most popular attraction in Dublin—in all of Ireland, in fact—the Guinness Factory is a kind of Disneyland for beer drinkers, not a working factory so much as a theme park. Perhaps a better comparison is an airport, as the visitor winds their way through the exhibits and attractions in the vast space on an endless series of walkways, escalators, and elevators.

This is making it sound as if I didn’t enjoy the experience. On the contrary, I found it to be well-designed and genuinely fun. Guinness is an institution in Ireland (indeed, the family is now the subject of a Netflix show), whose history goes back to the 18th century, when founder Arthur Guinness famously signed a 9,000-year lease on the property. It was thus a pleasure to learn how the beer and the brand evolved through time.

A few things are noteworthy about the company’s history. For one, Guinness pioneered a groundbreaking welfare scheme for their employees as far back as 1900, at a time when paid retirement was hardly even a dream among the working classes. This is praiseworthy, but the company has also indulged in its share of bigotry. For such a symbol of Irish pride, Guinness has historically been on the side of the Protestant British. Indeed, until as late as 1939 it would fire any employee married to a Catholic; and it would try to avoid employing Catholics until the 1960s.

Nowadays, however, Guinness is, as I said, an institution in Ireland, one of the country’s most iconic symbols. So it was a pleasure to end the tour in the “Gravity Bar,” which is on the very top of the factory building. With a panoramic view of the city of Dublin, it is a very satisfying place to enjoy its most iconic drink: a pint of Guinness.

I should include a little note here about the drink itself. It is often said that Guinness simply tastes better in Ireland. Although I can’t say I drink it enough to verify this, it does seem plausible. This isn’t because of the beer itself, I don’t think. After all, beer travels very well when it is properly bottled and stored. Rather, I think it is because Irish bartenders take a lot of care in pouring it properly. The procedure is always the same: fill it up about three quarters of the way, and let the foam settle for a couple of minutes. Then, the beer is finished with a good fizzy head of foam. By contrast, when I’ve had a Guinness in the U.S. it is either entirely too foamy or has no head whatsoever. And the proper ratio does add a lot to the drinking experience.

The evening was concluded with a visit to the Brazen Head, supposedly Ireland’s oldest pub. This was a repeat experience for me, though my mom greatly enjoyed both the ambience and the food. After that, we were ferried back to our Airbnb by one of the many loquacious cab-drivers in the city, who enthused to us about the nearby Croke Park, a stadium for Gaelic games. The Irish are an independent people, you see, and even their sports are unique.

The next day brought two more repeat experiences: the Book of Kells exhibit in Trinity College Dublin, and the National Archaeology Museum. I highly recommend both.

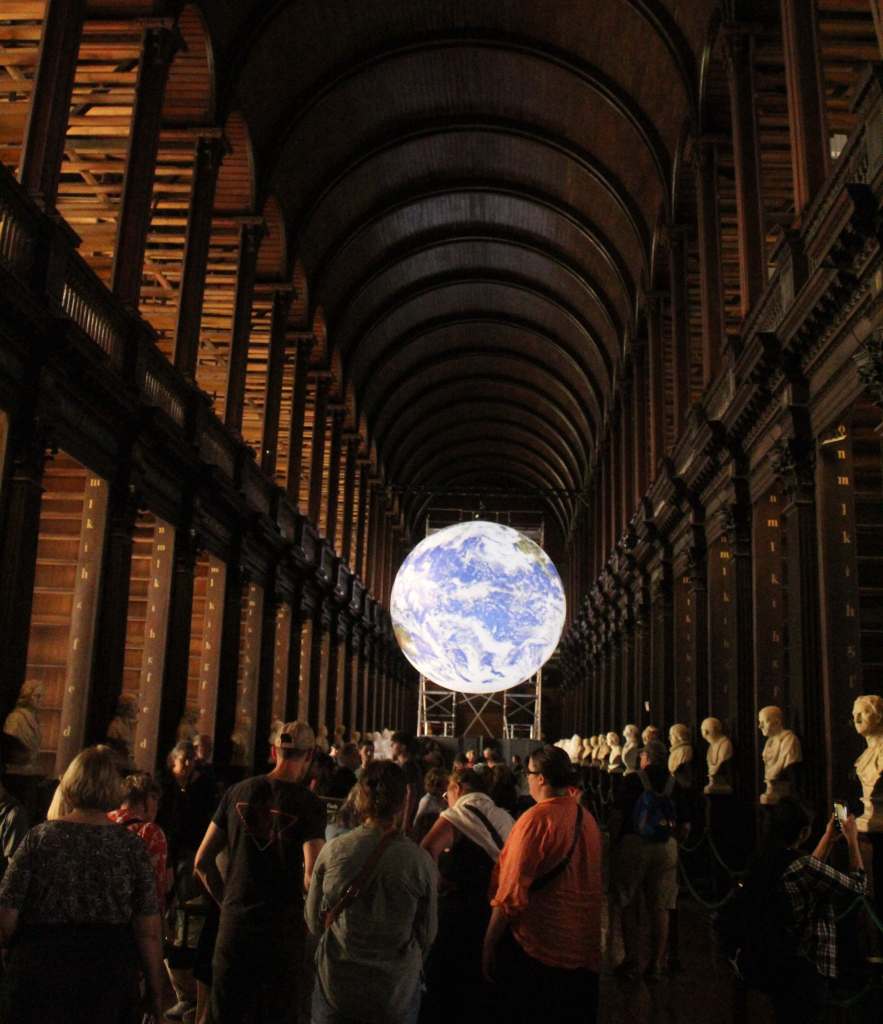

The Book of Kells is one of the treasures of European art—an intricately decorated copy of the Gospels. It is notable not only for its artistry but for its age: at a time when Europe was at its lowest cultural ebb, friars in remote Ireland were keeping the flame of culture alive. Trinity College is also worth visiting in itself for its historic campus, and especially its stunning old library. When I visited, the artwork Gaia, by Luke Jerram, was on display. This is an inflatable globe, lit from the inside, which looks remarkably like photos taken of the earth from space.

The Archaeology Museum is just as impressive. Housed in a stately neo-classical building, it has an amazing collection of objects from Ireland’s long past, from pre-history to the middle ages. This post is no place to delve deeply into the collection (I lack the knowledge for that, anyway), but I do want to mention the lovely gold ornaments from the Bronze Age, the well-preserved dug-out canoe from 2,000 BCE, and of course the famous bog bodies—naturally mummified corpses of men who seem to have been ritually sacrificed. The next time I visit Ireland, I intend to do a lot more preparatory reading about its history.

This was basically it for our initial visit. Luckily, however, we had an extra day back in Dublin before our departure. So I will now fast-forward to the end of our trip.

We dropped off our rental car and checked in to our hotel for the night, which was right above the pub, Darkey Kelly’s. Now, normally I am highly suspicious of hotel restaurants and bars, but this proved to be an excellent choice. This was because of the music. Seated in a circle, about 10 musicians—playing fiddle, accordion, bag-pipe, and guitar—were banging out tune after tune. And they were good. The melodies of these traditional Irish songs are quite fast, intricate, and bouncy, yet these players were perfectly in sync. It was a nostalgic way to end what was an amazing family trip.

The next day, before our hotel check out, we had a bit of time. Thankfully, there was a great museum nearby: the Chester Beatty. This museum is actually housed in a section of Dublin Castle. Despite the name, this is now more of a palace than a castle, though when it was originally built—as far back as 1204—it was a proper fortification. Indeed, Dublin Castle formed the nucleus of what is now Dublin. A body of water in this spot was known as the “dark pool,” whose Celtic translation gave the city its name. The old dubh linn has since disappeared; and the river which fed it, the Poddle, now runs underneath the castle.

The Chester Beatty is named after its founder, Sir Alfred Chester Beatty, who was actually an American. He led an interesting life. Beatty was a sort of Andrew Carnegie type, having made his fortune in the mining business. After a brilliant start to his career, he moved to London, and became ensconced in the upper echelons of that city’s politics and culture. He contributed significantly to the British Museum, and even played a role in the Allied war effort under Churchill. Yet the post-war Labor government seems to have scared off the capitalist American, and he relocated to Ireland in his old age.

Thus, it was Dublin, and not London, which inherited his magnificent collection of rare manuscripts. The collection is notable for both its beauty and historic value. Many of the items on display are lovely examples of illuminated manuscripts, from Chinese Buddhist sutras to illustrated Armenian gospels to delicate Islamic calligraphy. And several of the documents on display are enormously rare, such as the Biblical papyri, which are among the oldest surviving versions of the New Testament. The museum would be worth paying a high price to visit. And luckily, it’s free.

We went back to our hotel, packed our things, and headed to the airport—me to fly back to Spain, and my family back to New York. Our trip, so long anticipated, was finally over. And yet I am getting ahead of myself. For this was also just a beginning.