I turned twenty-one—the legal drinking age in my benighted country—in 2012, in the midst of a Renaissance in craft beer. I had spent most of college pounding cans of Coors Light, whose urinous flavor was offset by being affordable to college kids, with the added benefit that you could feasibly down ten or even twenty in a single night—a feat which naturally came with boasting rights. (I still have vivid memories of emptying dozens of cans from the huge recycling container in my dorm, and then vainly trying to get out the smell of stale beer by blasting it with hot water in the shower.)

It was something of a pleasant surprise, then, when I started drinking craft brews, and discovered that beer could actually be enjoyable in itself. Soon I grew fascinated by the variety and quality of the beers on offer. Breweries started popping up in every town. Even my local gas station began stocking dozens of different craft brews. Rather than simply tasting like watery piss, this beer could be bitter, chocolatey, aromatic, crisp, sweet, fruity, tart, and much else. For the first time in my life, I developed a palette for something, and began to keenly appreciate what had previously just been party fuel.

Thus it came as something of a shock when I moved to Madrid in 2015, and was once again thrown into the world of mass-produced beer. Whereas every self-respecting bar in the US will have at least five or six beers on tap, in Spain, even now, there is often only one. (You might think this is because Spaniards are mostly wine-drinkers. On the contrary, Spanish people drink beer in quantities surpassed by few countries.) I found it almost appalling that you could simply order “a beer” without specifying the type, only the size. Thus, I half-heartedly resigned myself to drinking lagers again, with the consolation that at least Mahou is better than Coors Light.

But all this soon began to change. Craft beer culture started catching on in a big way, and in just a couple of years Madrid was awash in local breweries. As it happens, one of my former coworkers at a school in Aranjuez, Luis, works nights at a brew-pub after he is done teaching. So one day I asked if he could teach me something about the art and science of craft beer.

Tenta Brewing is located on a shady lane in the small city of Aranjuez. The day I chose to visit was, fortuitously, the first day they were reopening after summer remodeling. I arrived early to help with the final clean-up before the doors opened, and in the process got a miniscule taste of the daily labor involved in owning a brew-pub. As I incompetently cleaned the floor, attempted to tidy the kitchen, and moved tables and chairs to places they weren’t supposed to go, Miguel—the founder, owner, and brewer of Tenta—lost himself in a tangle of tubes in order to connect the casks to the taps. At one point, I was tasked with sticking labels on some cans of beer. “Is there a machine for this?” I asked. “Yes there is,” Luis responded. “You!”

In any case, the restaurant work—setting up, closing up, cooking, cleaning—is only a fraction of the work involved in owning a brew-pub. The major task is actually brewing the beer. And in Tenta, this falls to Miguel. Considering that brewing beer is not something you normally study at university, the world of craft beer is populated by people of many diverse backgrounds. In Miguel’s case, he was a graphic designer for years before he even thought about hops, yeast, or malt. For Miguel, as for so many, the gateway drug was home-brewing. He started as a hobbyist and soon he was hooked. In 2022, the small beer factory finally opened its doors.

As it happens, I have also participated in the homebrewing experiment, though this merely consisted of following the directions on a beer-making kit. Still, it was instructive. Though the process was relatively simple, I was impressed by the scope for error. Every piece of equipment had to be carefully sanitized beforehand. Any deviation in timing or temperature could have fatally ruined the batch. What impressed me most was watching the beer ferment. For all the human labor that goes into beer-making, it is ultimately the yeast that do the heavy lifting—turning sugar into alcohol, and making carbonation in the process. Brewing beer, in other words, does not have the elegant precision of a chemical reaction. It is organic, and potentially messy.

Miguel spent the first two years of his brewing career as a “nomad.” This is a term for brewers who do not have their own factory, but instead make deals with other breweries to produce their beers for a slice of the profits. This is quite a common arrangement in the Spanish beer scene.

By chance, I stumbled upon a beer nomad at a neighborhood fair while writing this piece. In a tent sparsely furnished with a gas grill and half a dozen taps, Antonio (“Tojo” to his friends) was serving Dichosa beer. At the moment, he is brewing his beer in the factory run by Valle del Kahs (of whom, much more later), but he has worked with breweries all over the place.

When asked why he chose to brew his beer as a nomad rather than set up his own factory, he told me that there were several advantages. First, and most obviously, this allows you to avoid the fixed costs of equipment and upkeep. It also is a low-commitment strategy, which lets him move around to search for better arrangements. But the most curious advantage is that he can experiment with the water quality, which can vary quite a bit from place to place. (The water from Madrid is supposed to be exceptionally good, though.)

Even so, it seems curious that one beer maker would allow a rival to use their equipment. That would be like Chrysler manufacturing cars for Ford, right? Yet if you spend any time talking to beer-makers, you quickly get the impression that they do not consider themselves rivals of one another. Rather, there is a heartening spirit of camaraderie among brewers. Each one seems to know everyone else by name, and collaborations are frequent. The last time I visited Tenta, for example, they had a delicious watermelon ale on sale, made in collaboration with Pits, a brewery all the way up in Vigo.

Another reason for collaborating is simply business. Making beer is one thing, but selling it is quite another. Unlike the big-time brewing companies, which sell their beers in bars, restaurants, and supermarkets all over Spain, craft brewers have to work to find their audience. Though many brewers have their own pubs, at the rate that beer is sold in a brew-pub, the factory would remain under-capacity. This is why factory-owners gladly allow other brewers to use their equipment, in order to pick up the slack.

And this is also the reason why so many beer-makers put in long hours manning stands at local fairs and festivals (such as where I saw Tojo). Aside from these, there are dedicated craft beer events organized throughout the country by the Ruta del Lúpulo (the Hop Route). In these, a dozen or so craft breweries gather together, while the quickly inebriated visitor fills his glass from tent to tent. Even bigger is Beermad, a huge gathering of brewers in the so-called “crystal pavilion” in the Casa de Campo park. Local bands and food trucks are often recruited to round out the events.

Now, for my money, a well-made beer can be just as elegant, complex, and delicious as a fine wine. However, the culture of craft beer has little resemblance to the world of wine. For one, there are the aesthetics. While wineries present themselves as an extension of European elegance, the craft brew movement—at least as it exists in Spain—mostly takes its cues from my own country. English-language rock music blares from speakers, while men sporting beards and wearing band T-shirts and black jeans slide you a beer across the table.

Another, more important difference is that wineries are tied to the land in the way a beer-maker is not, or at least not necessarily. This is simply because wine is made from fresh grapes, which do not keep for long, while beer is made from malt (usually malted wheat, but other grains can be used), which keeps very well indeed. A beer maker could thus open a factory in Spain with malts from England and hops from the USA. Nevertheless, many beer makers try to give their product a local touch. Miguel, for example, acquires the fruits he uses to make his watermelon and strawberry beers from a neighboring village. Even the beef for the burgers is from local cattle.

One major challenge for Spanish craft brewers is that, unlike England, Belgium, or Germany, Spain has no autochthonous tradition of craft beer. Spanish drinkers—used to light, commercial lagers—are often unaccustomed to both the flavors and the price of the finer stuff. Still, the world of craft beer is cracking through the ancient drinking culture of Iberia; and nowhere is this more clear than in the Valle del Kahs brewery.

As its name would suggest, this brewery is located in the Puente de Vallecas neighborhood of Madrid. Traditionally a working-class, left-wing area, Vallecas has a strong sense of identity, and this is on full display at the Valle del Kahs pub. Tucked away into the narrow, maze-like streets of the barrio, the place looks nothing like a bar from the outside. And that’s because it wasn’t. The building was inherited by Dani, who owns the brewery along with his wife, Silvia. Before it was a bar, it was a bleach factory, operated for over 100 years by his mother’s family; and it still preserves much of its industrial atmosphere.

Dani’s family was thus one of the pillars of the neighborhood. As a case in point, his grandfather was one of the founding patrons of the Rayo Vallecano football team (soccer, for Americans), who play in the nearby Vallecas Stadium. Dani and Silvia have continued the tradition by sponsoring the Vallecas Rugby team. Trophies and jerseys adorn a corner of the bar, and portraits of the players—sporting jerseys with the Valle del Kahs logo—hang all over the bar. This logo, a growling black wolf, has a curious history. When Vallecas was far more rural, Dani’s father actually came across an abandoned wolf pup, adopted it, and called it Sultan. Dani barely remembers the wolf (he was too young), but the noble creature lives on as the company’s mascot.

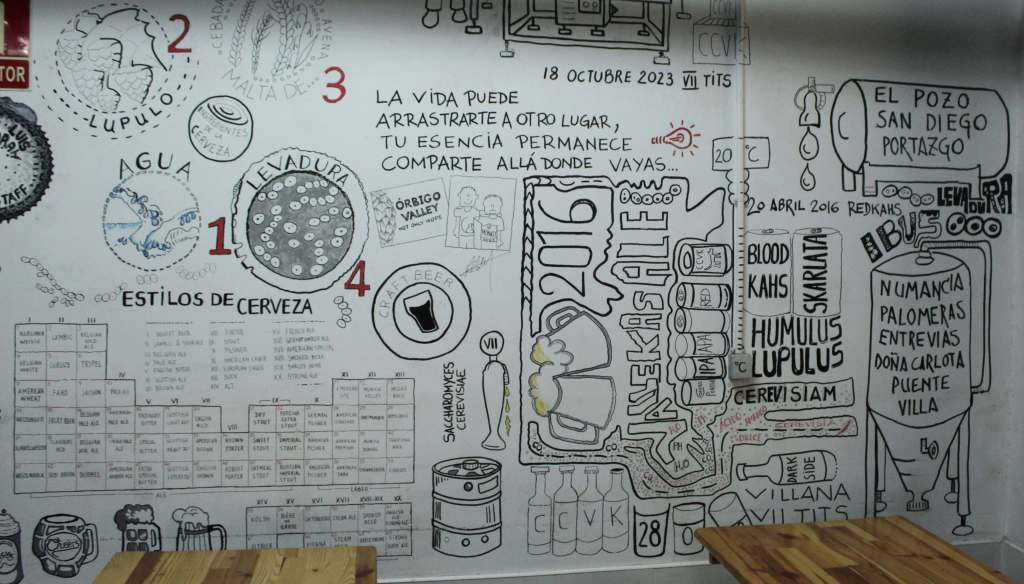

As with Miguel of Tenta, Dani got into the beer business via homebrewing. Beforehand, he was in marketing, but was dissatisfied with the high-pressure corporate environment. For her part, Silvia was a watercolorist before she began selling pints. But she continues making art, as evidenced by the diagrammatic drawings that adorn the walls of the bar, such as a periodic table of beer. Their son, Arturo, is now also a part of the business. He was a successful chef before the pandemic, but during the shutdown decided that he would devote his time to liquid rather than solid delights.

I met Arturo on a quiet Wednesday evening, deep in the Vallecas neighborhood. While the family originally made beer in the old bleach factory, last year they decided to rent out a bigger space for brewing in an industrial warehouse. There, Arturo was working alone, solely responsible for the enormous vats of boiling and fermenting malt. His rapid explanation of the beer-making process was punctuated by hisses from a huge compressor in the back, which was gathering and concentrating nitrogen gas to be used for extra carbonation.

Seeing him there, dwarfed and surrounded by shining metal devices, I was impressed by the scientific rigor required to make something so apparently simple. But there is nothing really logical about being a craft brewer. It means long hours of brewing followed by long hours of manning a bar. It means giving up a secure livelihood for one with an uncertain future. It means a constant, uphill battle. But when you see any of these brewers in their element, you know that they are motivated by something beyond good sense. For them, brewing beer is a labor of love.

loved the article, really insightful and well written

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot!

LikeLike

Really enjoyed this, great to know about craft beer around Madrid and Spain!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much!

LikeLike

Thanks a lot!

Really enjoyed the article and my photos 😛

Luhiggi

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m glad you liked it!

LikeLike

Qué buen artículo,por poco salgo yo pegando etiquetas😍

LikeLiked by 2 people

Jaja, muchas gracias!

LikeLiked by 1 person