“¡De Madrid al cielo!” is something people here like to say—meaning, I suppose, that Madrid is so marvelous that it can only be surpassed by a visit to heaven itself. And Madrid certainly is marvelous, not least for its big open skies, so often completely cloudless. Indeed, there are two institutions in the city dedicated to exploring the air and space above: the Planetarium and the Royal Observatory.

The Planetario de Madrid is a futuristic-looking building located in the south of the city, in the Tierno Galván park. Climbers scale the large concrete wall nearby, and electronic music festivals are often held in the park’s center. Constructed in 1986, the Planetarium gives the impression that it is how the designers imagined houses might look on Mars, in the distant year 2025.

Underneath the bulbous dome of the planetarium is a semi-circular screen, where educational programs are projected—cartoons for kids, documentaries for adults, and educational sessions for school groups. Through an oversight, I once sat through a film about velociraptors who constructed a space ship and traveled throughout the universe, only to return to earth and find the bones of their ancestors in museums.

Apart from these films, the Planetarium has a small exhibition space, where the visitor can see short educational films on the solar system, gravity, and the history of the universe. There are replicas of Mars rovers and space suits, as well as displays on the Milky Way and the moons of Jupiter. Most beautiful, I think, are the photos of distant galaxies and nebulae, taken by the Hubble Telescope and gently illuminated. The universe is a frighteningly beautiful place. All this being said, I think the exhibit space is rather light, and in general the Planetarium is geared towards younger audiences. Still, it is always worthwhile to contemplate the stars.

The Real Observatorio is certainly not a visit for kids. This royal institution was founded in 1790 by Carlos III, and it bears all the hallmarks of its Enlightenment origins. The Observatory is a kind of temple of science—housed, as it is, in a cathedral-like building designed by the great architect Juan de Villanueva. To visit, you need to reserve a spot on a guided tour, which are only available on weekends (and I believe are only available in Spanish). But if you have any interest in the history of science, the visit is certainly worth the trouble.

The tour begins in the great edifice of Villanueva, which preserves so much confident optimism of the Age of Reason. In the great hall, a Foucault pendulum hangs from the ceiling, making its slow gyrations. This device—the original of which hangs in the Panthéon of Paris—is a demonstration of the rotation of the earth, as the planet’s movement under the pendulum makes it appear to spontaneously change direction.

Distributed around the space were any number of beautiful antique telescopes and other scientific devices—crafted by hand out of polished brass and carved wood. Antique clocks hung on the walls in abundance, as if the scientists of that era had to double- and triple-check the time for their observations. In the main chamber, a large telescope occupied the center of the space. There, mounted like a canon, a metal rod is pointed at the slotted ceiling. Below it, a plush chair with a folding back allowed the scientist to look through it from either side.

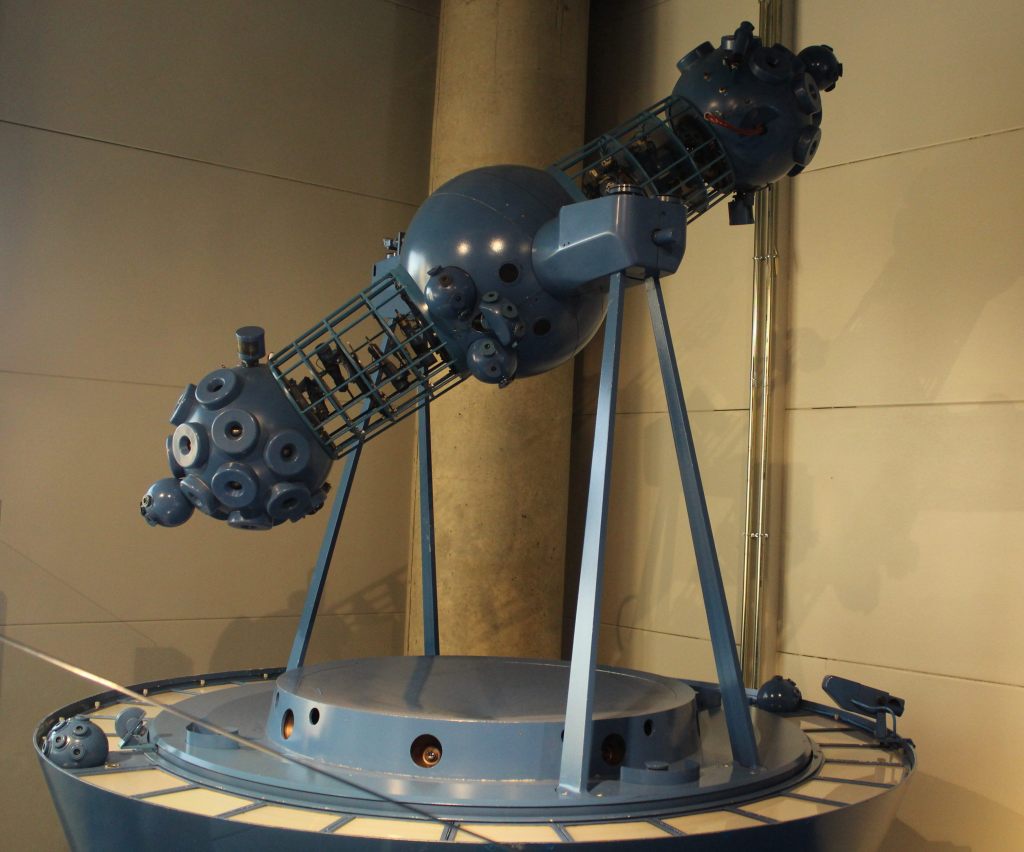

But the star attraction of the Observatory is held in a different building, a short walk from the Villanueva edifice. This is the great telescope of William Herschel, the English-German astronomer. This huge contraption was built in an English shipyard in 1802 for the new Royal Observatory. It was to be the center of the whole scientific enterprise. Unfortunately, fate soon intervened in the form of Napoleon, whose troops occupied the Royal Observatory (it has a strategic vantage point on a hill) just a few years later. These soldiers melted down the metal parts of the telescope for munitions and used the wood to keep warm. Thus, the current telescope is a careful reproduction, completed in 2004.

The tour ends in the Hall of Earth and Space sciences, a kind of miniature museum that is run by Spain’s Instituto Geográfico Nacional. The exhibit is divided into four sections: astronomy, geodesy, cartography, and geophysics. Each display is full of yet more scientific instruments, both old and new. There are armillary spheres (for determining the position of the planets in the sky), theodolites (for surveying land), and samples of volcanic eruptions from the Canary Islands. My favorite was a lithographic plate used in the printing of the National Topographic Map—the official, hyper-detailed, super-accurate map of the country.

The Royal Observatory is still an active scientific enterprise, monitoring both the skies above and the earth below—though the amount of light pollution in the city makes even Herschel’s great telescope largely useless. Instead, they receive data from far away telescopes, such as the Gran Telescopio Canarias, located high up in the mountains of La Palma, above the clouds and far from major city centers.

Yet even if Madrid’s skies no longer serve the purposes of science, they still inspire locals and visitors alike. As I write this, I am peering up at the blazing ethereal blue of a mid-September day, with the laser-like sun casting sharp shadows on the street below. It is, indeed, just one step short of heaven.