These three villages all lay on the road between Málaga and Cádiz, and make for very easy and pleasant stops along the drive.

Ronda

Of all of the beautiful villages in the south of Spain, Ronda may be the most famous. This is due to its dramatic location—perched high over the edge of a cliff.

Improbably, the two sides of this small town are separated by a massive gulf. For centuries, they were only connected by a relatively small bridge, built at a point where the height and width of the chasm are manageable, but far from the town center. It was only in 1793, after forty-two years of construction, that the massive “New Bridge” was completed, which spans the canyon at its tallest point. This was a major engineering challenge. A previous bridge, built in 1735, had collapsed just six years later, killing fifty people in the process. When the New Bridge was finished, it was the tallest in the world (98 meters, or 322 feet). Even for somebody used to skyscrapers, its dimensions are stupefying to behold in person.

More importantly, the bridge is beautiful. Made of the same rock as the surroundings, it seems to emerge from the landscape, as ancient as the cliffs themselves. The Guadalevín River flowing underneath it seems almost pathetic in comparison to so much towering rock—but, of course, it was the action of this patient little stream which cut this chasm in the first place.

My brother and I took the path down into the gully. The way down is relatively easy, the afternoon sun notwithstanding, and recommended if you want to get a real sense of the size of the bridge. I was disappointed to find that the path leading under the bridge and into the canyon had been closed off. On my previous visit, this was not the case. Once we had gone all the way back up to town, we were thirsty, sunburned, and exhausted, and decided to continue our drive towards Cádiz.

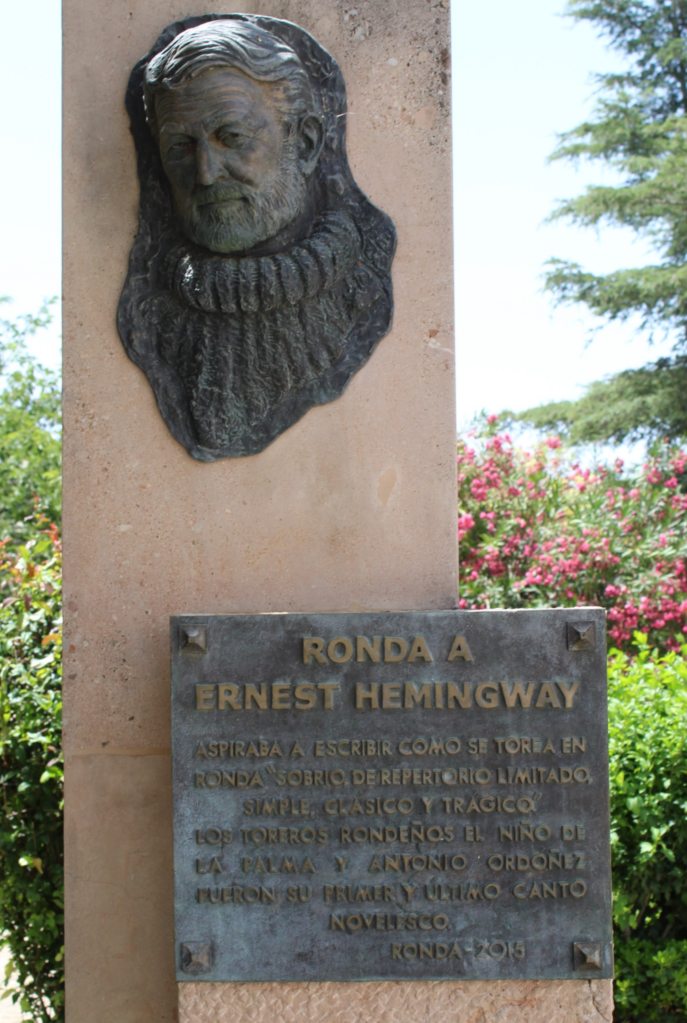

But Ronda has more to offer besides its iconic bridge. For one, the oldest bullring in Spain is in the city, and you can visit even if you do not want to see any animals slaughtered. There are ruins dating back to the town’s Muslim past, and lovely views of the surrounding landscape. Even without all of this, the town itself is a charming example of a whitewashed pueblo. No wonder that Orson Walles, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Ernest Hemingway were so fond of the place. Indeed, Hemingway set a major scene in his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls in Ronda; and though he embellished, it is actually true that prisoners were thrown into the canyon during the Civil War.

On that grim note, let us turn our attention to the next pueblo.

Arcos de la Frontera

We visited Arcos de la Frontera on our return journey to Málaga, when we did not have very much time to stay. Even so, it was a memorable visit.

The beginning was harrowing. My brother had innocently set the GPS to take us straight to the center of the village. However, this quickly appeared to be a bad idea as the road narrowed, twisted, and turned, leading us in a crazy labyrinthine path that was constantly diverted due to construction. Convinced I was either going to hit a pedestrian or scrape the side of a building, I was in a panic as we tried to navigate the tiny medieval streets. Finally, with some relief, I saw a sign informing us that only local cars were permitted to park in the center. We escaped the maze and parked the car in a grassy lot right on the edge of town.

The walk up was considerably more pleasant than the drive had been. The center of Arcos de la Frontera is impossible, located as it is at the top of a large hill. In just a few minutes we had arrived at the church that crowns the entire village, the Basílica de Santa María de la Asunción. As commonly happens in Spain, this church seems unnecessarily large and ornate for a village of some 30,000 people. The façade is ornately decorated, culminating in an elegant neoclassical tower. Unusually, the building’s massive buttresses extend over the adjacent street. The inside is just as elaborate as the exterior, with several fine altars and beautiful vaulted ceilings.

The plaza in front of the basilica is taken up, rather prosaically, by a parking lot. Next door is the local “parador,” which is the term for a historical building which has been converted into a state-run hotel (normally on the pricier side). Across the square is the town hall and, right behind it, the castle, at the highest point of the city. This castle is not open for visits; but the lookout point at the end of the parking lot is fully satisfying. As in Ronda, you are treated to a wonderful view of the Andalusian landscape—fields of crops, rolling hills, and not a modern building in sight.

As we had to drop the car off and catch our train back to Madrid, our time was limited. I can say with confidence, however, that Arcos de la Frontera is worth a much longer stay.

Zahara de la Sierra

Our next visit was the briefest of all. Indeed, we had not even planned on stopping to see any more pueblos. But the sight of Zahara de la Sierra—perched, like so many Spanish villages, on a rocky hill, presiding over a sapphire-blue reservoir—convinced us to at least stop for lunch.

This little town (population just shy of 1,400) is known for its meat stews, and that is what we ordered. Indeed, we had time to do little else. But I think any visitor who is not in a rush ought to climb to the top of the ridge and see the old castle, which still stands guard over the village. And it would not be a Spanish village without a beautiful and historical church—in this case, Santa María de la Mesa, a rather joyful-looking Baroque temple.

Unfortunately for us, we only had time to glance at the main attractions before we got back in the car and kept driving. Yet the drive itself—on the rural highways which connect Jerez de la Frontera with Málaga—was extremely lovely, and a wonderful way to close our long trip to Andalucía.

Taken together, this was a special trip in many ways. For one, it was an amazing relief to travel after being trapped in our tiny Madrid apartment for months. And this was probably one of the few times in recent decades that such iconic sites such as the Alhambra, the caves of Nerja, and the beaches of Cádiz could be visited with hardly any crowds. This was also the last trip I took with my brother in Spain, before his return to the United States to study law. As such, it was a little sad—but only just a little, since we really had a wonderful time.