Madrid has some of the finest museum-going in Europe, holding its own against Vienna, London, and even Paris. And this would be true if the city only had its big three: the Prado, the Thyssen, and the Reina Sofia. In addition to these heavyweight picture galleries, however, the city is also home to a great many excellent small museums. The best of these is, without a doubt, the one dedicated to Joaquín Sorolla.

It is somewhat ironic that Sorolla’s museum should be located in Madrid, as he was a valenciano by birth and disposition. His most famous and distinctive paintings are those featuring beach scenes, bathed in a kind of brilliant lucidity, every surface shimmering under the Mediterranean sun. But he was far more than a provincial painter. During his life, he became the most celebrated artist in the country—and, indeed, one of the most famous in the world. This is why he was able to afford such a fine house in the center of the nation’s capital.

The first thing the visitor will notice upon entering the museum is its lovely garden. This was designed after the Andalusian fashion, featuring colorful tiles, little aqueducts, and gurgling fountains. It is such an attractive space that some locals come here just to hang out, as it is free to enter. Sorolla designed the garden himself, and it is easy to picture him sitting here after a long day in his studio, resting his eyes.

The entrance to the ticket office is distinct from that of the museum itself. As it is a state museum, they charge the standard fee of 3€. It is free on Saturdays, but perhaps it is worth it to go on a different day, as the museum is most pleasant with fewer people. While purchasing your ticket, I recommend pausing to admire the Andalusian patio, as well as the painter’s impressive collection of Spanish ceramics. He seems to have had a keen appreciation for the rural, rustic handcrafts of his countrymen.

The first room of the museum is the picture gallery, featuring several excellent, large-scale paintings of the Spanish master. Here the visitor gets a good impression of his style. In his portraits—such as those of his wife or children—Sorolla’s work resembles other painters of his era, such as John Singer Sargent (whom Sorolla met and admired). He was more than capable of painting in a traditional manner.

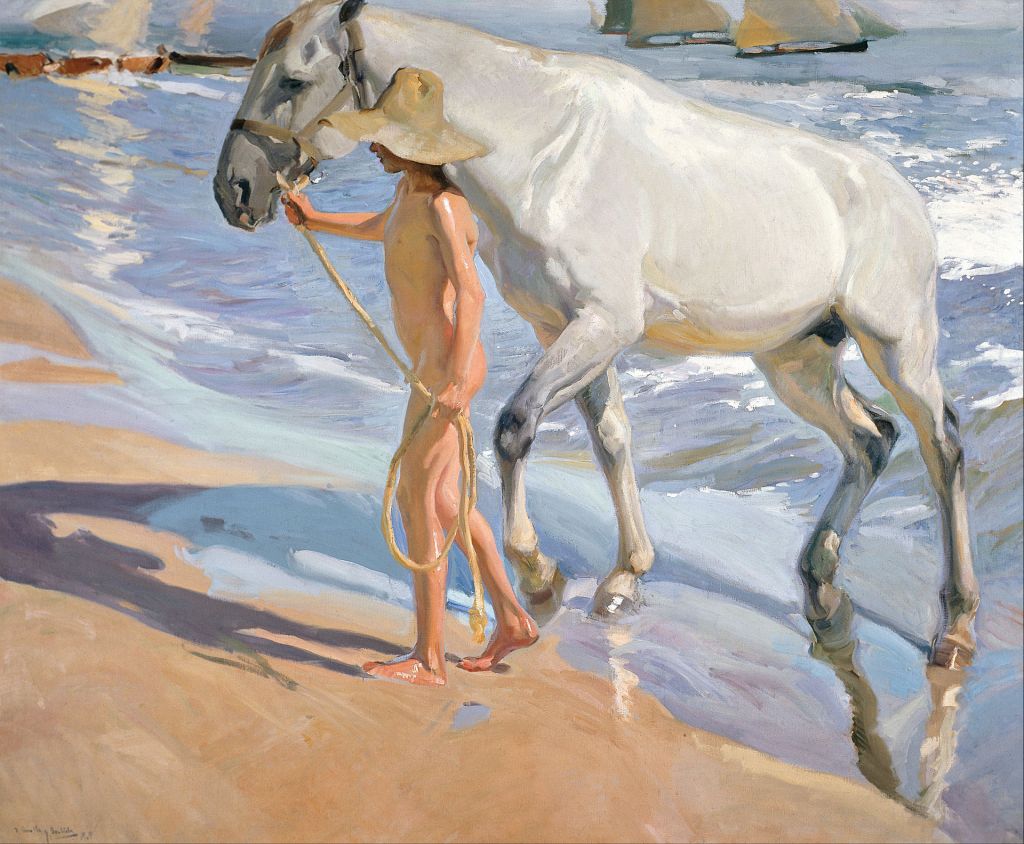

His brush comes alive, however, whenever he depicts bright, shining light. No other painter has captured the sensation of Spanish sun so successfully. His human figures seem to dissolve into gleam and reflection. In his beach scenes, you can smell the saltwater and hear the waves. If you have ever stayed on a Mediterranean beach long enough to go blind from the reflections and dizzy from dehydration, you can see that, in his paintings, Sorolla captured an experiential truth.

And though Sorolla was the epitome of a bourgeois artist during his lifetime, he was capable of great artistic daring. On my last visit, I was impressed by his work Madre, which depicts a mother in bed with her baby. Their tan faces are the only points of contrast with the white pillows, sheets, and walls, making it seem as if they were floating in a sea of light. There is nothing conventional about it.

The next room features some of Sorolla’s more familial works. Among the portraits we can find Joaquín Sorolla García, his son, who was the museum’s first director. It is largely thanks to him that we have such a fine museum, as he preserved it after his father’s death and left it to a foundation in his will. Unlike so many other house museums, then, nobody else ever lived here before it was turned into a museum. Another notable offspring we may find is Elena Sorolla. She became a talented painter and sculptor in her own right, though she later abandoned art in favor of her family.

The next room, Sala III, is the showstopper of the museum. It is Sorolla’s former studio. The space is ideal for painting, with large windows, a high ceiling, and skylights. Old, dirty paint brushes stand on a table, and a painting sits on the easel, half-finished, as if Sorolla just stepped out for a cigarette. The walls are covered in his paintings—so many and so high up that it is hard to even appreciate them. In the center of the room hangs a large copy of the Portrait of Pope Innocent X, by Velázquez (one of Sorolla’s heroes). Nearby is an ornate bed in one corner, which looks barely big enough for one person, much less Sorolla and his wife. Was it just for siestas?

The visitor next climbs the stairs into the temporary exhibition space. I have been to the museum many times by now, and have consistently been impressed with the quality of these exhibits. The museum has far more paintings in its collection than it can display at any one time (Sorolla was prolific), as well as objects and artwork from Sorolla’s own substantial collections. So there is a lot to choose from.

The last time I visited, they had an exhibit commemorating the 100-year anniversary of his death: “Sorolla en 100 objetos.” This is an attempt to tell the story of his life using Sorolla’s possessions. One gets the impression of a man whose career could hardly have gone any better—of an artist who achieved success early, and was highly respected until the end of his life. He is, in other words, at the other end of the scale from Van Gogh: not the lone, eccentric genius but a pillar of his community. And yet, judging from his massive output, one cannot rate his commitment to painting as any less than the Dutchman’s.

The rest of the museum consists of rooms furnished as they were during his time, whose richness only serves to exemplify the degree of success Sorolla enjoyed. The visitor is then, once again, deposited in the lovely gardens—to either bask in aesthetic pleasure or to be consumed by envy at such a fortunate life.

At the end of your visit, you will have a good idea of both the artist and his work. And yet, to see Sorolla’s most ambitious and monumental paintings, you will have to visit another museum—one on the other side of the ocean.

The Hispanic Society of America is perhaps one of the strangest and least-known museums in New York City. The name itself is misleading in two ways: first, because it isn’t and never was a learned society; and second, because—despite being located in Washington Heights, a “Hispanic” (meaning Latino) part of the city—it is really dedicated to Spanish culture.

In many ways, the museum is a relic from another time. It is the brainchild of Archer Milton Huntington, an eccentric millionaire who had a keen interest in all things Spain. Using his money (inherited) and his many intellectual connections (he was an amateur scholar), he assembled a collection of museums around Audubon Terrace—a monumental complex of ornate Beaux-Arts buildings—and had his wife, Anna Hyatt Huntington, add the sculptures and friezes.

(It is worth noting that Mrs. Huntington was a remarkable artist, who achieved widespread success at a time when it was very rare indeed for women to be sculptors, and who left many attractive monuments all over the Americas and Spain.)

Yet I am afraid that the decoration adorning the outside of the museum will likely rub some people the wrong way nowadays. Above Anna Hyatt Huntington’s wonderful statue of El Cid Campeador—the legendary hero of the Spanish Middle Ages—there are names inscribed on the outside of the building, as if to commemorate heroes. Yet the names include Pizarro, De Soto, Ponce de León, and Cortés—conquistadores, who are now more often reviled as destroyers than celebrated as civilizers.

The museum has a collection of art and rare books from Spain that is unrivaled outside the country. There are paintings by the big three—Velázquez, El Greco, and Goya—and even a first-edition copy of Don Quixote. For many years, however, this collection hasn’t been available to the public, as the museum had to undergo extensive repairs and renovations. I was fortunate enough to see some of this during my first year in Spain, when the Prado had a temporary exhibition showcasing some of the treasures of the Hispanic Society’s collection. But during my one and only visit to the actual museum, last summer, most of its collection was still unavailable.

But I was able to see Sorolla’s magnum opus: Visions of Spain. This is a truly massive series of oil paintings, all about 4 meters in height (12ish feet) and wrapping 70 meters (over 200 feet) around the room. Amazingly, despite this huge scale, Sorolla completed nearly all of these paintings outside, working en plein air at various locations around Spain. He must have needed a stepladder and a team of helpers.

The murals depict the many regions of Spain, focusing on their most distinctive qualities. We can see a Semana Santa procession in Seville, as well as some joyful flamenco dancing; in Aragon they dance the jota and in Galicia they listen to a bagpipe; in the Basque Country they play their distinctive ball game, while in Valencia and Catalonia they prepare the day’s catch of fish. By far the biggest painting depicts a bread festival in Old Castile, with both the famous cities of Ávila and Toledo visible in the background (impossibly, since the two cities are quite distant).

Now, judged purely as paintings, the murals in this series are perhaps not as pleasing as Sorolla’s finest individual works, such as El baño del caballo. They are too busy with detail to make for clean compositions, and do not always showcase Sorolla’s exceptional gift for portraying light. Judged by their scale and ambition, however, the paintings are absolutely remarkable. For such a large work, Sorolla paid exceptional attention to details of costume and custom, attempting to make his paintings as anthropologically informative as possible. And the execution is immaculate. It is no wonder that, after completing this series, the painter felt exhausted. He would die just four years later.

If a visit to the Museo Sorolla in Madrid proves that he was a wonderful painter, then a visit to the Hispanic Society in New York proves that he was something else: a patriot. Admittedly, this is not always an admirable quality in an artist (think of Wagner); but in Sorolla it drove him, not to bigotry, but to celebration of the scintillating beauty of his homeland—and not just its famous landscapes and monuments, but its people. For any who love both fine painting and that sunbaked land, his paintings provide a peculiar delight.