I got off the bus into a bright August day, climbed the stairs to the Meadowlands Exposition Center, and then gave my ID to a young man at the door. He handed me a lanyard that read: “COMPETITOR.” For the first time since high school, I was going to compete in a video game tournament. And it was a big one: Collision 2025.

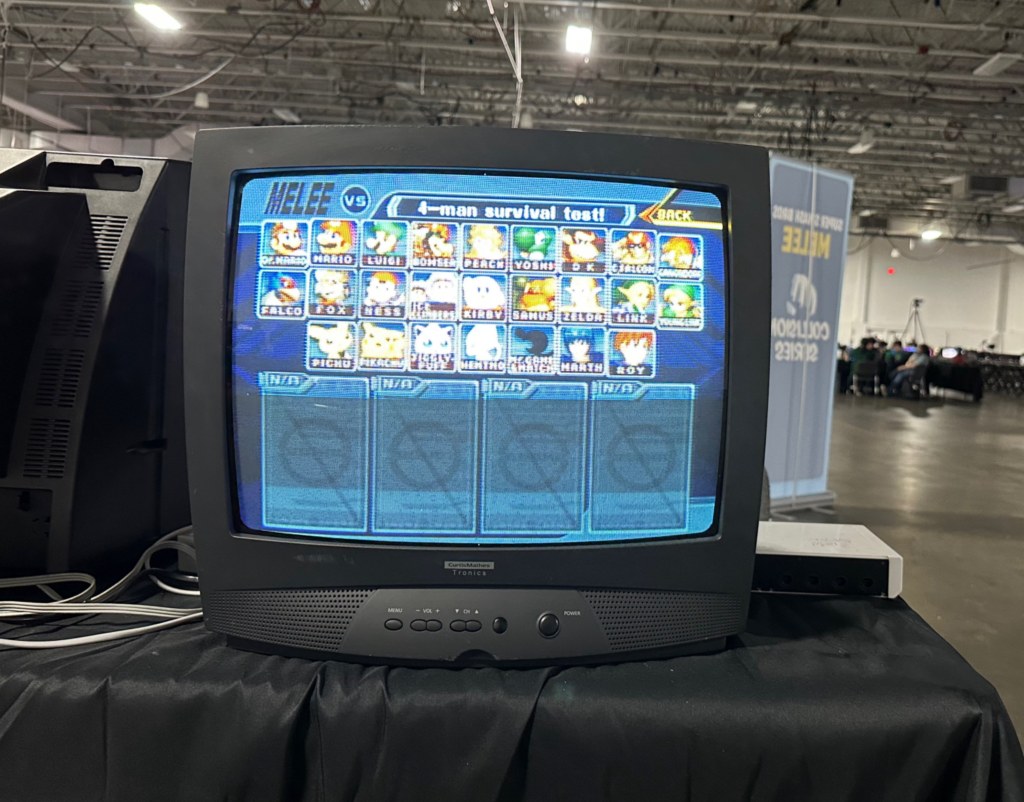

The space was huge, gray, and bare. On both sides of the cavernous room, rows and rows of monitors and consoles were set up, ready to be played. In the back was the main stage, where the final matches would be projected onto a big screen. By the time I arrived, early on the first day, relatively few people were about. The main events wouldn’t begin until the following day.

I walked around and tried to get my bearings. Nothing much was happening. A few dozen people were playing so-called “friendly” matches (not competitively), while others were simply milling about. Yet there was a quiet intensity to the space. Though the event was dedicated to video games in which cartoon characters beat each other up, it was clear that the attendees were not here to have fun. They were here to play, and to win.

Suddenly, a strange panic began to take hold. It was a feeling that I hadn’t had since I was a teenager: the paralyzing fear of being badly beaten at a video game. From the first moment, I could tell that I was simply not at the same level as even the average players here; and I felt sure that, if they saw me play, I would be laughed at. I felt ridiculous: a man at the age of 34, having lived in a foreign country, published several books, and worked for years as a teacher—paralyzed with fear at the thought of losing a video game. But the anxiety was real.

Indeed, it was so real that I had to leave the venue. Breathing heavily, I sat at a bus stop and even contemplated leaving, despite having paid a significant amount to sign up. But that would be cowardly, I decided. So I walked to a nearby diner, sat down, and ate an omelette. Then, still rattled, I walked to the Mill Creek Marsh Trail, a park that consists of a path through restored wetland. There, I took a deep breath, put on my headphones, and focused: “It’s just a freaking video game,” I told myself: “I can do this.”

I should give you some background. Super Smash Bro. Melee, released in 2001 for the GameCube, is the second iteration of one of Nintendo’s most popular games. Despite its age, the game is still played avidly: its fast and complex mechanics make it the most competitive version of the franchise.

As I’ve written about elsewhere, this game was a big part of my teenage years. I played it with friends and neighbors, and even brought it to school to play during breaks. And after one of my college suite mates brought his old GameCube to our dorm, I once again went through a heavy phase of Melee. But I hadn’t touched a controller since 2013, when I graduated college.

Despite this, I maintained an active interest in the game. Though I’ve never been a sports fan, I somehow became a fan of competitive Melee. Every so often, I would lose myself down a YouTube black hole, watching game after game after game. And this, despite fancying myself too enlightened and cultured for video games. For a long time, it was a secret vice. And despite my shame, I dreamed of someday playing it again.

Then, during my Christmas break, 2024, something fateful happened: my brother discovered our old GameCube in the basement of my mom’s house. Inside was Super Smash Bro. Melee. It even had our old memory card. For the first time in over a decade, I could play my favorite game. It was heaven: surrounded by all of my old friends, playing the exact game we used to play, rediscovering the pure joy of being kids. I enjoyed it so much, in fact, that I decided to take the GameCube with me back to Spain.

Eight months of practice later—most of it on my own, against the computer—I decided that it was time that I take my first real step into the world of Melee. My brother sent me the link to Collision 2025, a large tournament set to take place in New Jersey (indeed, so many important players would attend that it was classed a “supermajor”), and I decided that I had to sign up, even though I had no chance of even making it past the first round.

So here I was. I was still so nervous that I decided that I couldn’t allow myself to hesitate again. Thus, I walked back into the expo center, plugged in my controller into a free console, and started to warm up against a computer. After just a minute, however, somebody sat down next to me. “Wanna play?” he asked.

Thus began my own friendlies. As I expected, I was far worse than virtually everyone in attendance, and our matches mainly consisted of me being tossed around like a rag doll. Still, it was a fascinating experience—to finally see for myself how I measured against serious players. It was like playing against a professional tennis player after practicing in the park with friends: we were hardly playing the same game.

Yet much to my relief, everyone I spoke to was welcoming and kind, even as they whooped me. And I learned much about the game which I would never have learned by simply following it online.

For example, I discovered that controllers are an entire world unto themselves. Throughout the venue, there were several stands selling tricked-out controllers—for hundreds of dollars—or offering customization services, swapping out buttons and joysticks. And here I was, with an original, unmodified GameCube controller from 2001.

One player I played, JKJ (everyone goes by a “gamer tag” at these events; mine is Royboy), gave me a close-up look at his controller: it had fabric wrapped around the handles, and extra notches around the joystick. These notches are a controversial topic, as it makes it easier for players to angle their joysticks more precisely. JKJ explained that he thought notching was unsportsmanlike, but he started doing it because the practice is so widespread.

Another player I met—whose gamer tag I can’t recall, but whose real name was John—played with a different kind of controller entirely. It was a kind of black rectangle, the size of a traditional keyboard, but with much larger buttons. This is the B0XX Controller, which was developed by the smasher Hax$ (who died under tragic circumstances) for those suffering from joint and wrist problems.

“Are you squeamish?” he asked, after I inquired about the controller. I said “No,” and he showed me a video taken by his surgeon: his wrist was sliced open, and a gloved hand was manipulating his arm to show the tendons, muscles, and nerves. John explained that he was practicing on a traditional controller (“frame-perfect ledgedashes,” if you want to know the technique) when he felt something pop in his wrist. Apparently, a tendon had snapped out of its sheath, causing severe pain.

Now, after surgery, he has a scar and uses this ergonomic controller. Just because it is a video game doesn’t mean that you won’t get an injury.

I spent several hours playing and socializing before deciding to call it a day. The next day, Saturday, was when the real tournament began. At least I was warmed up.

For me, Melee is pure nostalgia. But the next day brought even more nostalgia, in the form of Jackie Li. Jackie grew up with me and my brother. He was over at our house so often that he might as well have been a third sibling. We would spend hours each day together. My mom would give him rides to school in the morning. He knew everyone in my family—even coming up to see my grandparents in the Catskills.

Like many kids, our main activity together was video games. We played them obsessively as kids. And Jackie was always the best. Nowhere was this more true than with Melee. Although I took the game very seriously, spending hours honing my technical skills, and although I could beat everyone else, often quite easily, I could never beat Jackie. He would win nine out of ten games, and no amount of practice ever seemed to bridge that gap.

My failure to beat him even followed me to college, as we both attended Stony Brook University. My suite mate got a GameCube, and I commenced to beat everyone who sat down to play me. But when Jackie came over, I still couldn’t win.

But all of us drifted apart after college. Partly it’s because I stopped playing video games, and partly it was simple neglect, and partly it was my move to Spain. But the impending tournament jogged my memory, and I decided that I had to reach out to Jackie. More than a decade had gone by, and I didn’t even have his phone number. So I sent him a message through LinkedIn. He agreed, and on Saturday morning he met me and my brother in Port Authority, looking just as he looked the last time I’d seen him.

Seeing somebody from your past after so long is almost trippy. It is a disorienting mixture of familiarity and strangeness. You know one another intimately, and yet hardly know one another at all. But it did make one thing clear to me: Our memories are stored in other people.

As I spoke to Jackie, huge swaths of my childhood came flooding back—nothing terribly important, but lots of little things, things that I hadn’t thought about in a long time.

So much of what we think of as “maturing” involves forgetting—leaving behind old identities that no longer serve us. There is definitely a power in this, the power of reinvention. But there is also a kind of spiritual danger, I think, since we can forget important aspects of ourselves.

Becoming an adult, I’ve found, eventually means integrating some of the identities we left behind, at least to some degree. And though it’s silly, I think my own changing attitude towards video games illustrates this process. When I was younger, video games were pure fun—absolutely engrossing, an escape from life, a competitive thrill. But at a certain point I forswore them: I decided that they were for losers, a huge waste of time, and brought out the ugly competitive side of players.

This was useful to me, since it allowed me to focus on socializing, on music, on school, and so on. But this left a huge part of my childhood as a black hole, a write-off. Now that I’m older, I’ve come to see video games as a qualified good. They are, after all, just a type of game; and our love of playing and creating games is one of our species’s most distinguishing qualities. Of course, their nature makes them more addictive than, say, Parcheesi. But nobody who has witnessed football culture in Europe, or even the steel-willed dedication of an avid chess player, can argue that video games are uniquely bad in this respect.

Indeed, crazy as it sounds, I am now inclined to say that Super Smash Bros. Melee must be one of the greatest games ever made. And now I was ready to compete.

The three of us entered the venue and sat down to play. Jackie was going to help me warm up before the tournament. This was like being in a dream. Here I was, over a decade later, ready to play my arch-rival—the one who I learned with, the one who always beat me. All these years later, what would the result be?

Strangely, anticlimatically, the result was nearly the same as it had always been: He still had a serious edge on me, beating me in about 90% of our matches. (It turns out that he was also practicing occasionally over the years.) And this brings me to another fascinating aspect of this game, and of games in general: the reality of skill.

Now, if you don’t know much about Melee, the game could seem to involve a great deal of luck. After all, players are making split-second decisions in situations that, chances are, they had never seen before—at least not in that precise configuration. The same is true of many games and sports: to the untrained eye, they seem to be up to chance as much as skill. But the reality is that skill is something as real and tangible as a controller: it is measurable and tends to be fairly consistent through time.

The results of the tournament speak for themselves: the first, second, and third place finishers (Zain, Hungrybox, and Joshman, respectively) were the first, second, and third place seeds. In other words, the results were exactly what was anticipated based on the player’s rankings.

This is not to say that there weren’t “upsets.” The 4th-place finished, lloD (a practicing doctor, as it happens), was seeded 13th; and the 7th-place finisher, Zamu, was seeded 23rd. Clearly, a player’s official rank isn’t a perfect reflection of their skill at a given moment (and we should be grateful for that, as the game would be boring to watch otherwise). But what strikes me as more notable is that even these “upsets” weren’t radical miscalculations. It is not as if a player came out of nowhere to finish in the top 8.

Another striking feature of skill is how it can appear to follow an exponential scale. I will illustrate this point with my own tournament experience. My first-round opponent was a player who went by “notsmoke.” He beat me handily, winning every game by a significant margin. The set was over in less than 10 minutes. But as soon as I congratulated my opponent, his second-round pick sat down for the match. This was Agent, a ranked player, who proceeded to beat notsmoke nearly as badly as I’d just been beaten. Agent was, in turn, knocked out handily by Zuppy, who in turn was eliminated without much ado by Moky. And on and on.

The striking thing about all this is that, to me, the skill levels of (say) Agent, Zuppy, and Moky appear to be nearly indistinguishable, and yet there are significant chasms between each of them. And the gap between Moky and Zain (the winner of the tournament) is just as significant still.

To round out my own tournament experience, I had one more match to play before I was knocked out entirely. My new opponent was ENFP, who beat me even more dramatically than notsmoke (though rather politely, I should add). And that was it for my stint as a competitive gamer.

The rest of our time at the Meadowlands Exposition Center was just spent watching. And here I want to add a note on the demographics. As you might imagine, the large majority of the attendees were male (stereotypes do sometimes hold true). But I was surprised, and charmed, by the significant number of trans people. When I was a kid, video game culture was quite misogynistic and homophobic (and perhaps corners of it still are); but now, players are introduced along with their pronouns. Most everyone was in their 20s and 30s, though some were considerably younger. For example, one up-and-coming player, OG Kid, is (as his name suggests) still a teenager—meaning that he is younger than the game itself.

One jarring aspect of the tournament was seeing so many famous players. Virtually all of the major competitors were in attendance, with the notable absence of Wizzrobe (who dropped out last minute), Cody Schwab (the current #1 player), and Mang0 (often considered the greatest player of all time, who had just been banned due to his drunken misbehavior at another event). Everywhere I looked, there were faces I recognized: Axe, Salt, Junebug, Aura, Nicki, Aklo, Jmook, Trif… I was starstruck, but then realized that none of these people is, in truth, really famous. They were legends only in the context of a fighting game that is over two decades old.

Floating among the crowd, his hair died blond, was Zain—the current #2 player and the heavy favorite to win. He was surrounded by people who knew exactly who he was, who admired and envied him; and yet he seemed to be separate from the crowd, just drifting from place to place. At one point, he stood next to me as I observed a match—the tournament’s eventual winner next to its last-place finisher. And it occurred to me that I had never stood so close to somebody so good at anything.

Zain stood there—alone in a mass of people dedicated to this game, people who had collectively devoted hundreds of thousands of hours to honing their own skills—secure in the knowledge that he could beat any one of them. And it made me reflect on why people devote themselves to such seemingly pointless activities.

Aside from fun (and the game is very fun), the most obvious answer is escapism: to focus your attention on something unrelated to your daily life, where there are no consequences. But that is not the whole story. For some, it is the community—being a part of like-minded people, the chance to make friends and share interests. And the game also offers an opportunity to forge a new identity— nerdiness transmogrified into coolness.

But for Zain, and those like him, I realized that they were here for something else: the pure pursuit of a skill—skill for the sake of itself, being the best they could be at this one specific task. There is something almost inhuman about it—requiring, as it does, such single-mindedness of purpose that everything else in life becomes secondary. And yet, in a way, this pursuit of skill for its own sake might be the most human quality of all—the quality that drives us to the highest reaches of excellence.

But there is a high price to pay. The irony is that, thanks to my reunion with Jackie, I probably enjoyed the tournament quite a bit more than its champion. And to enjoy things you’re bad at—to enjoy them, especially, with old friends—is also a very human quality.