This is part of a series on Historic Hudson Homes. For the other posts, see below:

- Washington Irving’s Sunnyside

- John D. Rockefeller’s Kykuit

- Alexander Hamilton’s Grange

- FDR’s Springwood & Vanderbilt Mansion

- Thomas Cole’s Cedar Grove and Frederic Church’s Olana

- Jay Gould’s Lyndhurst & Untermyer Garden

Of the many famous names associated with the Hudson Valley—John D. Rockefeller, Alexander Hamilton, Washington Irving, just to name a few—one name looms over them all: Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He needs no introduction. As president, he guided the nation through two existential threats; and he did much of his work from the home where he was born, overlooking the Hudson River.

The young cousin of the great Teddy Roosevelt—whose own stately home Long Island, Sagamore Hill, has also been turned into a monument—Franklin was from a wealthy family. His father, James, had a degree in law but chose to stop practicing, having received an ample inheritance. It was James who purchased the property in 1866, which he dubbed “Springwood” (a fairly bland name, if you ask me). And it was here, on January 30th, 1882, that his son Franklin was born.

When Franklin himself inherited the house, in 1900, he set about expanding and improving the place. Children notwithstanding, the extra space was mainly to house his collections of books, prints, model ships, stuffed birds, and other paraphernalia. He was apparently something of a packrat. But the result of this remodeling is a beautiful neoclassical structure—grand, without being grandiose.

Having been donated to the government two years before his death, the furnishings of the house are perfectly preserved. Often these are just the sort of things one might expect to see in the house of a patrician: fine furniture, oil paintings, expensive pottery. But a few things stick out in my memory. The most impressive room in the house is Franklin’s library, a beautiful space with dark, polished oak bookshelves filled to the brim. Other rooms are surprising for their simplicity. The bedrooms are anything but luxurious; and the dining room, though elegant, hardly seems big enough for the entourage of the head of state.

Undoubtedly the loveliest aspect of the house is its location. The view of the Hudson Valley from its upper floors could hardly be improved. It is no wonder that the young Franklin came to have a keen appreciation for natural scenery—doing more to expand America’s national parks than even his mustachioed cousin.

The tour of the house is relatively brief. After that, the visitor is free to explore the grounds. Nearby are the stables (Franklin’s father was an avid horse breeder), and I was amused to find a plaque for a horse named “New Deal.”

But the most moving spot on the entire property is Franklin’s tomb. As per his instructions, he is buried in his garden, where a sundial used to stand, encircled by roses. His tombstone is plain white marble, devoid of any decorations. The president died unexpectedly at the age of 63, of a brain hemorrhage, after being elected a record four times. His body was carried in a grand and somber procession to this place, as the shocked nation mourned his loss.

Interred with him is his wife, Eleanor, who died seventeen years later, in 1962. She was just as much a revolutionary as her husband, and transformed what it meant to be First Lady. If I had properly done my research, I would have gone to see her famous residence, Val-Kill, which is about two miles east of Springwood. Eleanor purchased this property along with two women’s rights activists, Nancy Cook and Marion Dickerman. There, they put into practice their idea of handicrafts (heavily influenced by the art critic John Ruskin), teaching locals to make pewter and furniture.

The site is perhaps more interesting for its LGBT history, as Cook and Marion were romantic partners, and Eleanor herself had a long relationship with the journalist Lorena Hickok. (FDR, for his part, had a prolonged affair with Lucy Mercer Rutherford, Eleanor’s social secretary. You can say that they had a modern marriage.)

Closeby is Top Cottage. Aside from Jefferson’s architectural wonders in Virginia, this is actually the only building designed by a sitting president. It is certainly not a showpiece. Indeed, the cottage was primarily designed to be more wheelchair accessible, after his bout with polio in 1921 left FDR’s legs paralyzed. Curiously, then, Val-Kill and Top Cottage reveal how two normally marginalized groups—the LGBT and the disabled communities—were connected to the center of power during one of the country’s most perilous periods.

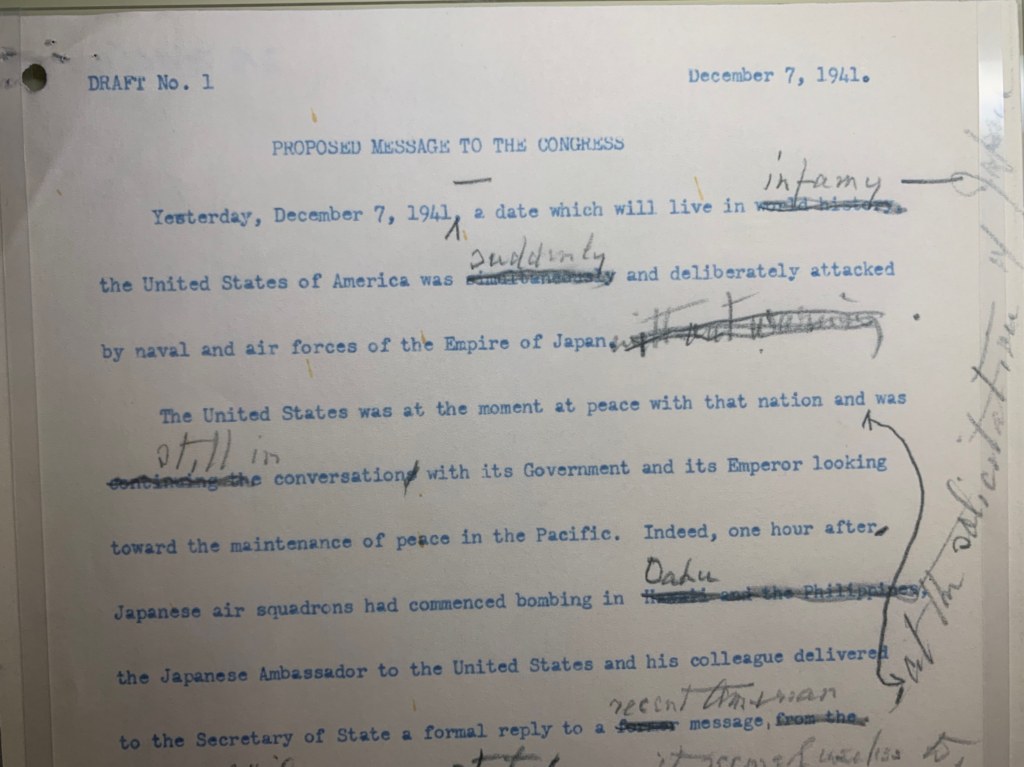

To get back to Springwood, however, no visit to the property is complete without the museum, located in the Henry A. Wallace Center. Now, normally I am not a fan of exhibits which consist mainly of long texts with historical photos. It always strikes me that the information would be better displayed in a book or magazine, rather than distributed throughout a building. Even so, I enjoyed the long biographical exposition of FDR’s life, and learned a great deal.

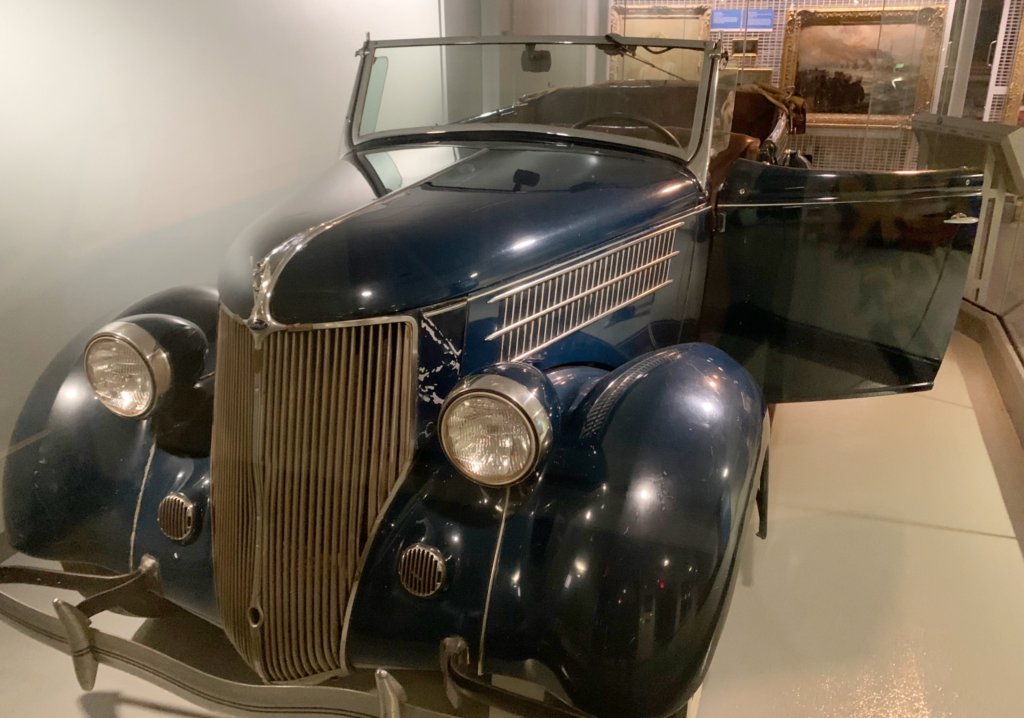

The visit culminates in the basement, with FDR’s iconic Ford Phaeton. It was modified to allow him to drive with his hands, and he keenly enjoyed driving. There is an excellent chapter in Winston Churchill’s memoirs of the Second World War, in which he describes a visit to Springwood, where he was terrified by Franklin’s tendency to race around the country lanes. But Churchill had nothing but praise for the hospitality he received in Hyde Park.

Now, a visit to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Historic Site would be more than enough to fill a day. But the visitor is spoiled by being able to also pay a visit to the Vanderbilt Mansion, which is located just up the Albany Post Road.

The name Vanderbilt is nearly as synonymous with old money as Rockefeller. The dynasty began with Cornelius Vanderbilt (1764 – 1877), who managed to transform his father’s modest ferry business into a railroad empire. Upon his death he bequeathed the vast majority of his riches to his oldest son, William Henry, often called “Billy.” Understandably, the other Vanderbilt descendents were not happy with this arrangement, and this led to a lengthy court battle—which Billy eventually won, thereby becoming the richest man in America.

Billy was a careful guardian of his father’s empire. Though he survived his father by just nine short years, he managed to double the family’s wealth during that time. But he did not decide to imitate his father in leaving all of his wealth to his oldest son. Rather, he split his money between his eight children. While admirably equitable, this fairly well ended the Vanderbilt Empire, as his children proceeded to squander the family fortune, leaving very little for the next generation.

As a case in point, while Cornelius and Billy lived in (comparatively) modest circumstances, the grandchildren built a series of mansions across the United States. All told, they left 40 elaborate dwellings, many of which have become monuments. Among the best-known are Marble House, Rough Point, and The Breakers, all in Newport, Rhode Island. And the most famous of them all: Biltmore Estate, still the largest privately-owned residence in the United States, in Asheville, North Carolina.

The Vanderbilt Mansion in Hyde Park belonged to Frederick William Vanderbilt. Of all of the grandchildren, he was perhaps the most reserved and upright. The ostentatious mansion notwithstanding, he managed to preserve his inheritance and lived free of scandal, quietly devoted to his wife Louise.

But there is nothing quiet about this house. It is palatial, making the Roosevelts’ Springwood look puny by comparison. Every room is decorated to the highest standards of Gilded Age taste—the American nouveau riche imitating European aristocrats. As far as furnishings go, it is a convincing copy: a photo of the interior could easily pass for the house of an English country squire.

My clearest memory of the tour was the guide’s description of their daily routine. It was leisure elevated into a formal art, with rigid rules. Men and women both had different attires for different times of the day—for some light outdoor sport, then for cocktails, then for dinner—and each hour came with its specific sort of alcohol. I imagine mustachioed men in tuxedos, drinking copious quantities of port wine and filling the room with cigar smoke, while their wives sat on the divan in the next room, sipping sherry in elegant ball gowns. It was the transmutation of alcoholism into sophistication.

The tour ended in the servants quarters in the basement—shockingly bare and utilitarian compared with the extravagant luxury in the house above. It was a stark reminder of the huge staff whose (poorly remunerated) work was necessary to make a life like this possible.

When Frederick Vanderbilt died in 1938—having survived his wife by twelve years, and never having had children—he bequeathed his estate to his niece, Margaret. Yet by this time, the huge Gilded Age mansion was a relic from another age; and his niece understandably had little interest either in living on the property or in paying for the upkeep. Her neighbor Franklin thus easily persuaded Margaret to donate the mansion and its property to the United States government (for the token sum of $1) to be turned into a national monument. In fact, FDR occasionally used the property to house his secret service and some visiting guests.

At the end of the tour, we asked the guide (who was excellent) where we could get a local bite to eat. He recommended the nearby Eveready Diner. And as I took a bite of my hamburger, I reflected that I’d just had a wonderful—and a wonderfully American—day in the Hudson Valley.