Jerez de la Frontera

After our stays in Granada and Málaga, our next base of operations was Jerez de la Frontera.

If you know some Spanish, you may recognize that this name translates literally into “Sherry of the Border.” But this has an explanation. For one, sherry wine is named after Jerez, not vice versa; the original name “Jerez” goes all the way back to Phoenician times. And the place is referred to as occupying a “border” because, during the middle ages, this town was on the border between Christian- and Muslim-controled areas.

After dropping off our things, the first thing we did was to visit the city’s Alcázar. Now, there are “alcázars” all over the country. The name—like most Spanish words beginning with “al”—comes from Arabic, in this case from al-Qasr, meaning a castle or a fortress. This one was built in the 11th century, when Jerez was part of a small Muslim kingdom. The conquering Christians added to the fortress. Even so, the fortress—with its horseshoe arches and baths with star-shaped vents—is an excellent example of Moorish architecture. And the walls provide an excellent view over the city.

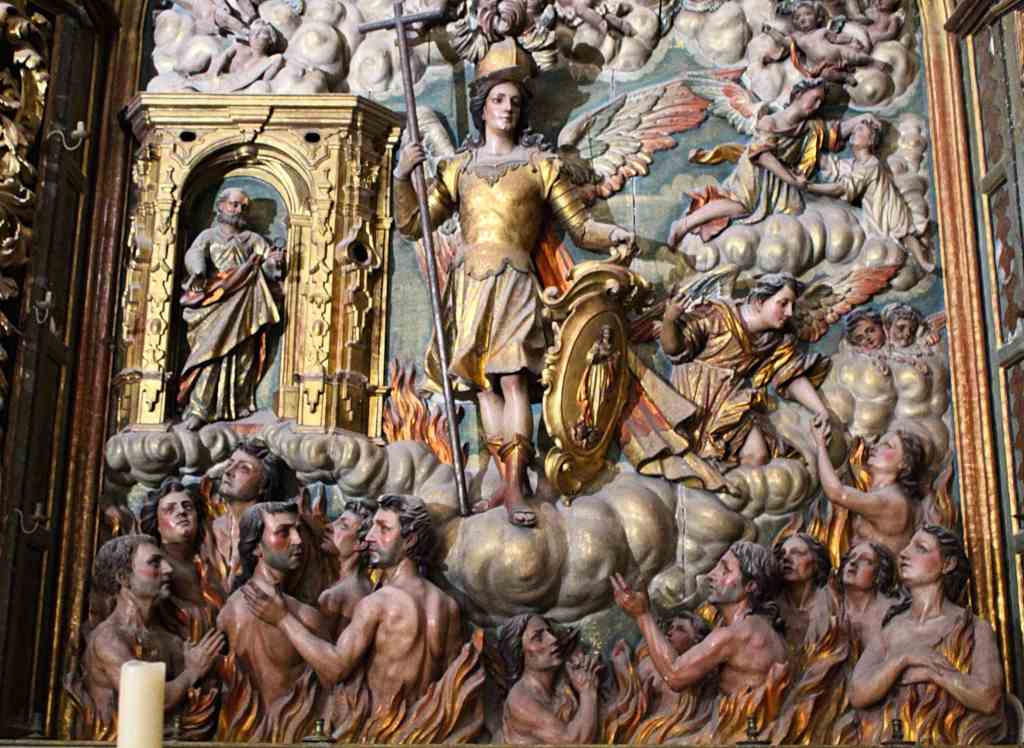

Next we visited the city’s cathedral. This is quite a grand building. But if you are used to the scale of European cathedrals, it may strike you as on the smaller side. This is because it was not originally built as a cathedral, but as a collegiate church which was later “promoted” to the status of cathedral in 1980. In any case, it is a lovely building with gothic flying buttresses and baroque decorations on its façade. Even lovelier might be the Church of San Miguel. If memory serves, the opening hours of this church are rather limited (and they aren’t posted online). But if you manage to get in, you will be rewarded with striking gothic vaults and richly-carved altarpieces.

But the highlight of Jerez is not, in my opinion, any monument. Rather, it is the wine. We happened to arrive on a Sunday and most of the major wineries were closed. But after calling several in a row (getting through to a janitor in one of them), I finally reached a man who seemed rather surprised on the phone. He said he had a totally flexible schedule and that we could come any time we liked. Like an ignorant American, I suggested five o’clock, but he quickly told me that it would be too hot then, and that seven would be far better.

We arrived punctually at Bodegas Faustino González. An older man with white hair was waiting for us. He introduced himself as Jaime, and led us inside. It quickly became apparent that this tour was just for the two of us. And it was also quickly apparent that we had inadvertently chosen a beautiful bodega. (In Spain, a “bodega” is a winery, not a corner store.) In a simple white warehouse there were long rows of barrels, stacked three barrels high. Jaime explained that this is the standard way of aging sherry. The bottom barrel is known as the “solera,” from the word for floor (“suelo”). This is the basis for the wine, as the solera is never entirely emptied. Thus, it preserves the distinct character of any particular winery. Then the sherry is moved up to the next barrel, a “criadera” (literally a “breeding ground”), and finally to the last one. This process takes at least two years, often far longer.

(The barrels, by the way, are made of American oak. Once they are too old for sherry, they can be sold to Scottish Whiskey makers, where they continue to age fine spirits.)

Jaime took a device known as a “venencia”(basically, a cup on the end of a stick), stuck it into a barrel, and let us taste the fresh wine. It was fresh and quite tart. He explained that dry sherry is normally made with palomino grapes, which are white. There are several varieties of the wine, which can be divided into two main groups: manzanilla and fino (white, clear, plain), and amontillado, palo cortado, and oloroso. These latter three kinds are oxidized during the aging process, giving them a dark, rusty color and a far more aromatic flavor. (For my money, oloroso is consistently the best.)

Many exported sherries are basically sold as cooking wine, and taste like finos with added sugar. But if you really want to taste a sweet sherry, you’ve got to try Pedro Ximenez. This wine is made from the grapes of the same name, which are left to dry into raisins before they are turned into wine. This makes the final product almost black in color and incredibly sweet. The flavor is intense—almost too intense to drink, like maple syrup. In fact, I used the bottle I bought from the winery to pour over vanilla ice cream, and found it to be extravagantly delicious.

As you can probably tell, my brother and I were delighted by the visit. We emerged, about two hours later, very satisfied and quite drunk (we had been given about six glasses of sherry), and wandered off to find something for dinner. I have subsequently bought sherry from Jaime and can attest to its excellent quality.

During our time in Jerez, we managed to visit another winery: González Byass. Its name comes from its founder, Manuel María González, and his English agent, Robert Blake Byass. (There is a charming statue of Manuel near the cathedral.) This is possibly the biggest and certainly the most famous producer of sherry. The iconic Tío Pepe fino sherry—whose mascot is a bottle dressed in a red sombrero and jacket, holding a guitar—is from this company. Any visitor to the Puerta del Sol, in Madrid, will recognize it: an advertisement which has been elevated to a symbol of Spain. (An even more famous symbol of Spain, the Osborne Bull, also originated as an advertisement—for sherry brandy.)

The tour lasted about an hour and was with a group of about twenty people. I imagine that it is more difficult to secure a spot on a tour during normal times. Right after the lockdown, we were given a spot on the very next group. Compared to Faustino González—an artisanal producer, with a single warehouse—this winery was enormous. It is also, obviously, famous. There were bottles dedicated to heads of state and signed by celebrities (notably, Orson Wells). Indeed, according to our guide, the most attractive of the warehouses, La Concha, was designed by none other than Gustave Eiffel, on the occasion of a queen’s visit. (It appears, after looking it up, that this is not really true. Though commonly attributed to Eiffel, “La Concha” was designed by an English firm.)

Finally we were ushered into a posh bar for a tasting. Though I can hardly be called an expert in this ancient art, the difference between the handcrafted sherry of the previous visit and this industrially-produced wine was immediately apparent. The sherry from González Byass tasted simple and even bland by comparison. In fairness, the GB products are significantly cheaper and easier to find. And I certainly would not turn down a glass of their oloroso.

Cádiz

Jerez de la Frontera is a delightful city by itself. But one of its best qualities is its close proximity with Cádiz. Indeed, aside from Venice, I would rank Cádiz as the prettiest city in Europe. And unlike that Italian icon, Cádiz is a place where people actually live.

Cádiz is located on a small peninsula that juts out into the Atlantic ocean. It is an extremely old place, inhabited since at least the 7th century BC. Arriving from Jerez is a breeze: the local train takes you right there in about 45 minutes—treating you to some arresting views of the landscape and the ocean along the way.

The first thing any visitor to Cádiz ought to do is to simply walk around. The buildings form a coherent color palette: made of tan stone or painted pastel colors. The inner streets are narrow and winding, like those of any city with a long pedigree. But go too far in any direction and you emerge onto the open sea. Even on a hot day, the breeze makes it tolerably cool, and if it is sunny the ocean shines a kind of delirious turquoise. (You can probably gather that I am fond of Cádiz.)

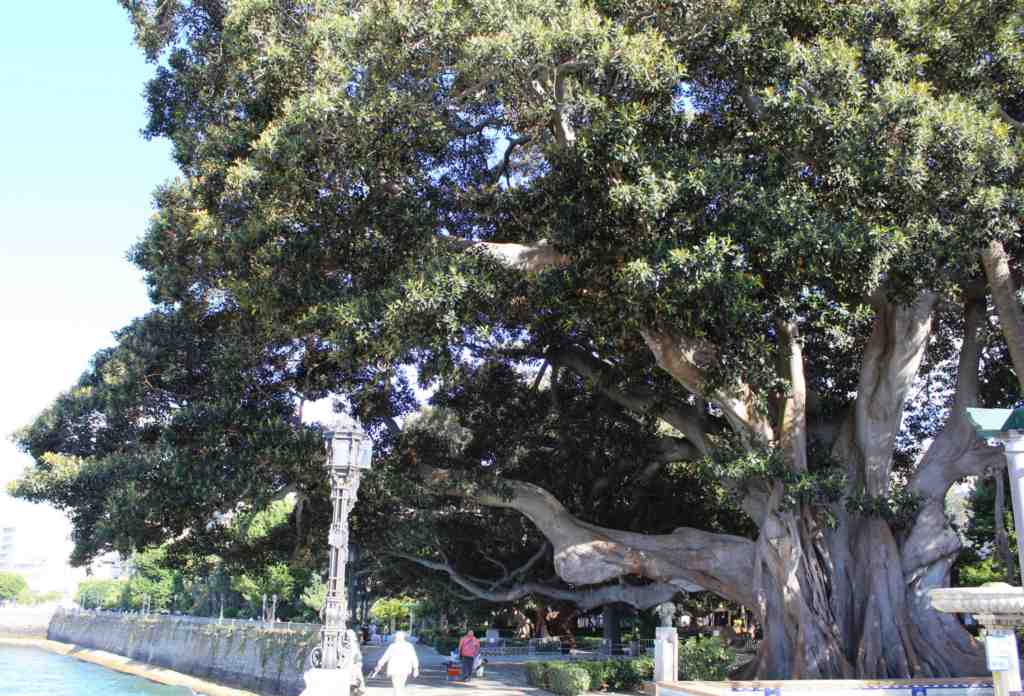

One of the most attractive parts of the city are the Gardens of Alameda Apodaca, which is located alongside the water on the Northern side of the peninsula. It is a kind of garden walkway, with flowers hanging from trellises. At the end of this garden you reach two strange and enormous trees. These are Australian Banyans, which have special supporting structures known as “buttress roots,” which spread over the ground to support the enormous canopy. An equally lovely park is the Parque Genovés, which is full to the brim with exotic plants, such as a Drago tree (from the Canary Islands), a Metrosideros (from New Zealand), and a Norfolk Island Pine (from Australia).

As you can perhaps tell from these exotic trees, Cádiz is (or was) well connected with foreign lands. Indeed, the city owes its wealth to being the primary port of trade between Spain and her American colonies for several centuries. Of course, this source of revenue abruptly ended when Spain lost her empire in the 19th century, which is one reason the city is still so quaintly beautiful. If that had not happened, then doubtless Cádiz would be full of modern glassy skyscrapers.

After a stroll around, my brother and I were in the mood for lunch. For the hungry or the morbidly curious, the Mercado Central is worth a visit. On the inside you can see an enormous collection of freshly-caught seafood, still covered in ocean brine. There are piles of squids and shrimp, and tuna as heavy as a person. If this whets your appetite, you can get something to eat in any of the dozens of food stalls running along the outside. I would certainly recommend sampling the seafood. Local specialties include tortillitas de camarones (shrimp fritters) and cazón en adobo (marinated dogfish)—both quite tasty, in my opinion.

After our meal, we visited the Cádiz Museum. Normally, this institution has exhibits which range from prehistory to the 20th century. But when we visited, it was under renovation, and the upper floors were closed. This was fine with me, however, as the section on ancient history was still open, and this is what I especially wanted to see.

As I mentioned before, Cádiz has a very long history, and the museum has artifacts dating from well before the era of Socrates and Confucius. But the two most famous artifacts are two Phoenician sarcophagi, carved in the form of a man and a woman, made some time around the year 400 BC. The male sarcophagus was discovered all the way back in 1887, with a well-preserved skeleton still inside. The corresponding female was found almost an entire century later—coincidentally just outside the former home of a museum director—during a routine construction job. The two tombs are quite lovely works of art, showing possible Greek influences but still unlike any Greek statue I have ever seen.

Perhaps the best way to get a tour of Cádiz is to visit the Torre Tavira. This is a former lookout tower, now the second-tallest structure in the city (after the cathedral). The views from the top are worth the fee to go up. But your visit also includes a kind of remote tour using a camera obscura, reflecting light from outside onto a large dish, while a guide points out all of the major landmarks in the city. It is certainly a touristy experience, but one I do not hesitate to recommend.

(The cathedral, I should mention, is also certainly worth a visit. Unfortunately, it had yet to reopen after the lockdown when my brother and I visited.)

The next site I want to mention did not figure on our itinerary. But as I visited two years later, with Rebe, I think it worth including here for the sake of information. This is the Gadir Archaeological Site. Gadir is the original, Phoenician name for the city, and this site takes you directly into the ancient past. As fate would have it, the site is located under a puppet theater. Visits are conducted by guided tour only, which means you must reserve at least a little bit in advance. During my visit, the tour was conducted by one of the archaeologists who actually did work on the site, which made for an especially interesting experience. The ruins are not visually impressive (consisting of the outlines of buildings and streets), but the information revealed about ancient lifeways was fascinating.

But of course, I cannot end a post about Cádiz without mentioning the beach. There is an extremely long beach—Playa de la Cortadura—running along the road that connects Cádiz with the mainland. Far more beautiful and iconic, however, is La Caleta, which is at the very end of the peninsula. My brother and I spent two evenings lounging under the shade of an old spa and taking dips in the ocean, from which I can conclude that it is a thoroughly lovely spot. (This spa building, by the way, is itself an icon of Cádiz. It was built in 1926 with long, sweeping arms suspended over the sand. The spa went out of business, however, and nowadays it is the headquarters of the Underwater Archaeology Center.)

La Caleta is made especially picturesque by being flanked by two castles. On the right is the Castle of Santa Catalina, built around the year 1600. There is a small exhibition center inside and a good view of the beach. (I also think there is a hotel somewhere in the castle.) On the left side is the Castle of San Sebastián, which is located on a small island off shore, and connected by a thin walkway to the beach. It is possible that a Greek temple occupied this spot millennia ago, but the castle was built around the year 1700. The last two times I visited Cádiz the castle was closed, though the very first time I went I could go inside (and there was not much to see). In any case, the walkway is attractive enough to merit a visit.

That does it for our trip to Jerez and Cádiz. As great as were Granada, Málaga, and the little towns we visited, these two cities were easily the highlights of the trip. There is little that can compete with a cold glass of exquisite sherry followed by a swim.