The first time that I went to Coney Island, I was in college, fully in the grip of a newfound commitment to intellectualism. I was certain that I was going to be a professor, that I was going to be a prolific and influential author, and that most of the world was consequently not up to my exacting standards of culture, taste, and intelligence.

At that moment in my life, Coney Island struck me as the epitome of everything I hoped to reject. Tacky, cheap, loud, dedicated to the pleasures of the flesh, it was horrifying to me. I did not like the beach, or roller coasters, or even funnel cake. It was too hot, too full of naked skin, too shamelessly mindless. I know that I sound as if I were some sort of dreamy Hamlet, condemned to a layer of Dantean hell, but that is what it felt like. Though it pains me to think of it, I was once invited to a birthday party in Coney Island; and rather than play catch on the beach, I spent the time under the boardwalk, reading James Joyce’s Ulysses (which, to be sure, I completely failed to understand).

And yet, Coney Island is so pure in its embodiment of wanton fun that I was also, against my will, fascinated by it. While I felt superior, the place also made me feel as if I was missing something fundamental about life. It became, for me, a symbol of what I lacked, and that is basically how I described Coney Island in my novel Their Solitary Way.

With age comes wisdom, or at least acceptance. It took me time, a long time, to learn to relax and have fun. Now, a decade and a half after my first visit, I think Coney Island is one of the treasures of New York, something I look forward to every summer.

For about a century now, Coney Island has not been an island. Formerly, the Coney Island Creek separated the island from the landmass of Long Island; but a part of this creek was filled in in the 1920s. However, as “Coney Peninsula” doesn’t have quite the same ring, the original name was retained. Aside from Rockaway, Coney Island is the only beach accessible on the subway (and the ride is significantly shorter), and it is also the only amusement park.

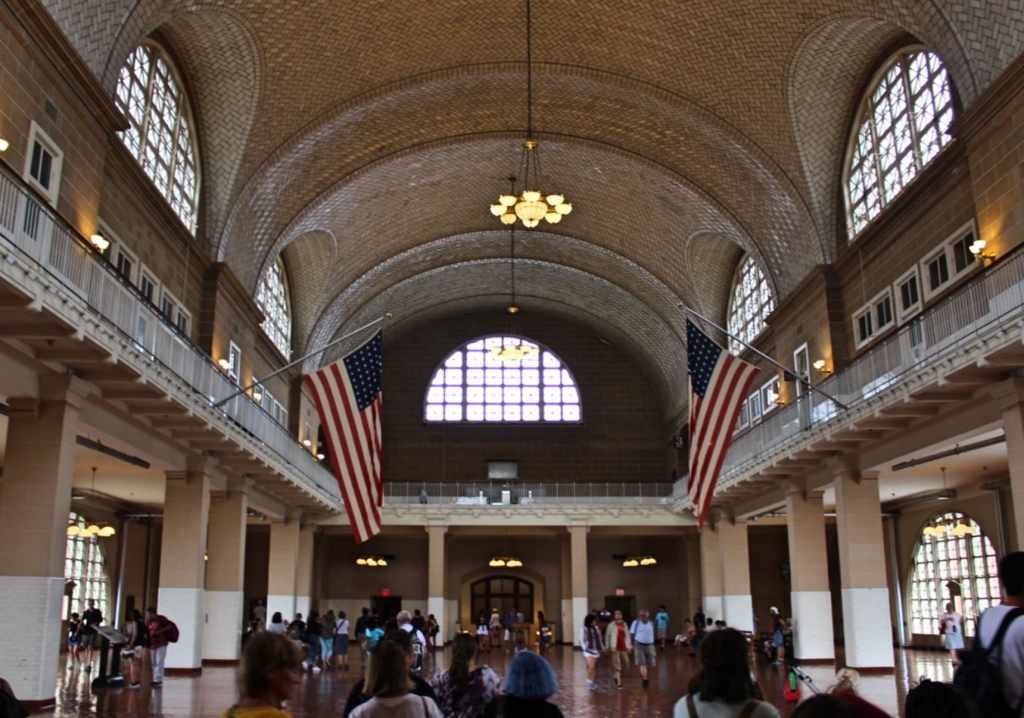

Coney Island has been the playground of New York since the 19th century. This is evidenced by the grandiose Coney Island – Stillwell Avenue station, which is the terminus of lines D, F, N, and Q. With its eight individual tracks, it is more reminiscent of a train station than a lowly subway stop, and is obviously built for high volume.

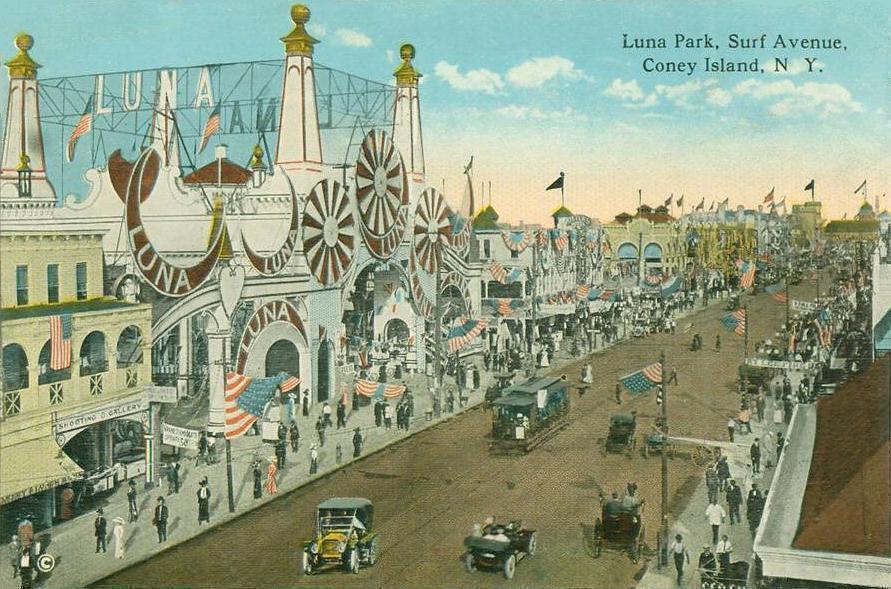

As you walk around the “island” today, buzzing with beach-goers, dancers, tourists, baseball fans, and teenagers on line for various rides, you might be forgiven for thinking that Coney Island is now in its golden age. But the peak of Coney Island occurred from the 1880s to the Second World War. During that time, with three amusement parks operating—Luna Park, Dreamland, and Steeplechase—it was the largest amusement area in the United States.

An early symbol of Coney Island’s greatness was the Elephantine Colossus, a 122-foot tall wooden building in the shape of (you guessed it) an elephant. It was so big that it could be used as a concert hall, a palace of petty amusements, and even a brothel. Indeed, it was significantly bigger than the earlier Elephant of the Bastille, a plaster model of a planned—but never executed—statue, which became an attraction unto itself. (It is now famous principally for Victor Hugo’s description of it in Les Miserables.) Unfortunately, the wooden structure burned down in 1896; but there is another huge wooden elephant in nearby New Jersey, by the same designer: Lucy the Elephant, in Margate City.

(There is a far darker elephant story connected with Coney Island, that of Topsy the elephant. Topsy was a circus elephant who had a reputation for misbehavior. In 1902 it was decided that the elephant would be executed as a publicity stunt. With the blessing of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Topsy was poisoned, strangled, and electrocuted. Her electrocution was actually caught on film. This film survives, and it is gruesome to watch. Be it noted that Thomas Edison had nothing to do with this particular animal execution, though it was filmed on an Edison camera.)

But the powers that be were not always kind to the island. One way to demonstrate this is the history of the New York Aquarium. This institution was originally housed in Battery Park, in the historic Castle Clinton, and was free to the public. It was a beloved place, visited by millions per year. Yet it attracted the ire of the infamous park commissioner, Robert Moses—who disliked both the aquarium and Coney Island for being too plebeian—who forcibly transferred the aquarium from Castle Clinton to Coney Island.

This had several unfortunate results. For one, the new aquarium was forced to charge admission. (Currently the price is $30, which is so steep that I have never visited.) The aquarium was also unable to safely transfer their animals, leaving them with no choice but to release their collection into the ocean and begin from scratch. And last, the aquarium was deliberately put in real estate previously occupied by the amusement park, Dreamland, in order to reduce the tawdry attractions.

But an even bigger nemesis to the island was Fred Trump—Donald’s father. A real estate developer, Fred eyed the valuable property occupied by the former Steeplechase Park, and eventually acquired it with the aim of putting up high-rise apartments. He made sure to demolish it quickly, and publicly, before it could be given landmark status; but he was ultimately unsuccessful in his building project. Trump eventually sold the property back to the city, and it was duly turned back into an amusement park.

Nowadays, the only remnant of the old Steeplechase Park is the iconic Parachute Jump. This was a ride that consisted of strapping people into a seat, pulling them up to the top of a 250-foot tall tower, and then letting them fall to earth with a parachute. It sounds extremely dangerous, but the ride apparently had a perfect safety record. The now-defunct ride is strangely beautiful—a kind of blooming steel flower.

This information, I should note, was partly gleaned from the Coney Island History Project. As its name implies, this is a non-profit organization, dedicated to exploring, recording, and divulging the history of Coney Island. In the summer months, they run a small stand near the Wonder Wheel, where the visitor can see remnants of old rides (such as the steeplechase), as well as dozens of excellent old photographs.

The center portrays Coney Island as a haven of cheap fun, which had to survive decades of private greed and public neglect in order to serve its vital function to the city of New York. We have already heard about Robert Moses and Fred Trump; but before them, John McKane, a Tammany Hall politician, tried to sell off much of the publicly owned land for profit. (Unlike the corrupt politicians of later eras, McKane ended up in Sing Sing.)

Fred Trump’s demolition of Steeplechase Park, in the 1960s, inaugurated what was perhaps the darkest period in the island’s history. As its popularity among New Yorkers declined—a result of many factors, such as the rise of the automobile, and the new availability of other recreational sites—much of Coney Island was rezoned and redeveloped for urban housing, with large buildings constructed for lower-income residents. This was followed, predictably, by an increase in crime and a consequent decrease in legitimate business.

It was only in the late 80s that a movement got underway to protect and revitalize the area. The Coney Island Cyclone, the Parachute Drop, and the Wonder Wheel were declared landmarks, and plans were made to construct a minor league baseball stadium on the former site of Steeplechase Park. Of this stadium, more later. First, I want to pay my respects to the classic rides of Coney Island.

The oldest continually operating attraction on the island is the Wonder Wheel. Built in 1920, it has operated every year except 2020, during the pandemic (unfortunately, its centennial). Its design is unlike a standard Ferris wheel, in that some of the compartments can slide around between the rim and the hub. Despite being next to the larger Luna Park—which operates all of the major roller coasters—the Wonder Wheel belongs to its own separate amusement park, Deno’s. Named for Deno Vourderis, who acquired the wheel in 1983, this is a family-run amusement park, still operated by his two sons.

Only slightly younger than the Wonder Wheel is the Coney Island Cyclone. Built in 1927, it was actually the third of the great wooden roller coasters, after the Thunderbolt (1925) and Tornado (1926). The former stopped operating in 1982, but was not demolished until 2001; the latter was destroyed by arson in the 70s. The Cyclone narrowly escaped destruction, too, after it was acquired by the city in order to provide land for an expansion of the Aquarium. The Coney Island Chamber of Commerce fought the aquarium to a standstill, and the plan was eventually scrapped.

The Cyclone is now the star attraction of Luna Park. Despite its age (or, rather, because of it), the ride holds up. Reaching a maximum speed of 60 miles per hour, it manages to be quite terrifying, as the loud clackety-clack of the car, careening over the spiderweb of ancient wood, gives the sensation of imminent collapse. The sense of riding a rickety antique provides a thrill no modern technology could duplicate.

The current Luna Park is a reincarnation. The original was opened in 1903; and judging from the photos and illustrations, it was a sensational place. With over a million lights—changing color every second—it had every sort of entertainment conceivable. Its name comes from its first and most iconic ride, “A Trip to the Moon.” In this, visitors would travel on a strange spacecraft, as scenes of earth and space were projected on the walls. Then, they would “land” on a papier-mâché moon, where the Man in the Moon would dance for them. It sounds pretty awesome.

(This brings us back to the unfortunate life of Topsy the elephant. This elephant was acquired by the owners of Luna Park in 1902, and used to advertize the construction of the new park. This included hauling the “spaceship” used in A Trip to the Moon. However, the drunken handler started stabbing Topsy with a pitchfork during the move. The police intervened, and the handler responded by turning the elephant loose, causing predictable havoc. Two months later, this dangerous man rode Topsy directly into the police station—again, causing predictable havoc. Topsy’s execution was thus framed as “penance,” though it was timed as a morbid publicity stunt for the park’s opening. The past wasn’t always such a charming place.)

The Luna Park that exists today only shares its name with that original park, which closed in 1944. The current rendition opened quite recently, in 2010. It has dozens of rides, from spinning teacups to terrifying slingshots (which I would never try). Among these is the new Thunderbolt. Opened in 2014, this is a modern-style rollercoaster, with a completely vertical lift hill (possibly the scariest part of the ride), and four sections when you are momentarily upside-down. Surprisingly, its top speed is a hair under the Cyclone’s; and the comforting impression of modern engineering makes it ever-so-slightly less terrifying.

But an amusement park isn’t just rides and roller coasters. An essential element are the carnival games. Coney Island is teeming with such amusements, from Whac-A-Mole, to the ring toss, to miniature basketball free-throws. When I was younger, I steered clear of these games, put off by their vaguely unscrupulous aura. Yet now I think a couple dollars is a fair price for the pleasure of spasmodically attempting to bludgeon some plastic vermin. And I was pleasantly surprised when I actually won a game of water racer (in which you have to fill a container using a water pistol), and was awarded an enormous pillow featuring the likeness of Lebron James. The world may not always be fair, but sometimes you get lucky.

Yet there are pleasures even more acute than these. On a whim, after a long day on the island, we decided to dip into the Eldorado Bumper Cars, on Surf Avenue. It was like walking into a nightclub. Dancehall music blared deafeningly from the speakers as we blinked in the neon darkness. Deliriously, I handed over my ticket, and was directed to one of the waiting cars. The power was switched on and I lurched into motion, careening endlessly around a track, while a teenage boy clipped me from behind with an inscrutable smirk on his face. It was a blast.

As it happens, this bumper car establishment is next to a Coney Island institution: Nathan’s Famous. This is the original location of what is now a hot dog empire. It was founded in 1916 by Nathan Handwerker, though the hot dog recipe was created by his wife, Ida—who, in turn, got the spice blend from her grandmother. Nathan was a Jewish immigrant from Poland, who used his entire life savings—a grand total of $300—to open a hot dog stand with his wife. The hot dogs were all beef, though they were technically not kosher (the animal has to be slaughtered and prepared a specific way) leading Handwerker to dub them “kosher-style.”

Over a century later, Handwerker’s small stand has expanded into a city block, and in the summer months it is consistently packed. Yet with cashiers and counters on three sides of the building, service is surprisingly fast. Now, I am not normally a huge fan of hot dogs—in flavor, color, and texture, they are so processed as to be food-adjacent—but Coney Island, the mecca of mindless fun, is the perfect setting to stop worrying and love the glizzies (as they kids call them nowadays). And insofar as such things can be judged, I actually do think the Nathan’s frank, with mustard and sauerkraut, is a cut above the average wiener.

Nathan’s is also famous for being the site of one of America’s most barbarous rituals: its July 4th Hot Dog Eating Contest. The contest has a mythical origin story, in which four immigrants decided to test their patriotism with an impromptu contest, all the way back in 1916. But the contest really dates from 1972, when it was dreamed up as a promotional event. Though it began rather informally, the contest is now the World Series of the professional eating world. Indeed, for something as silly as an eating contest, there is a surprising amount of drama in the “sport.”

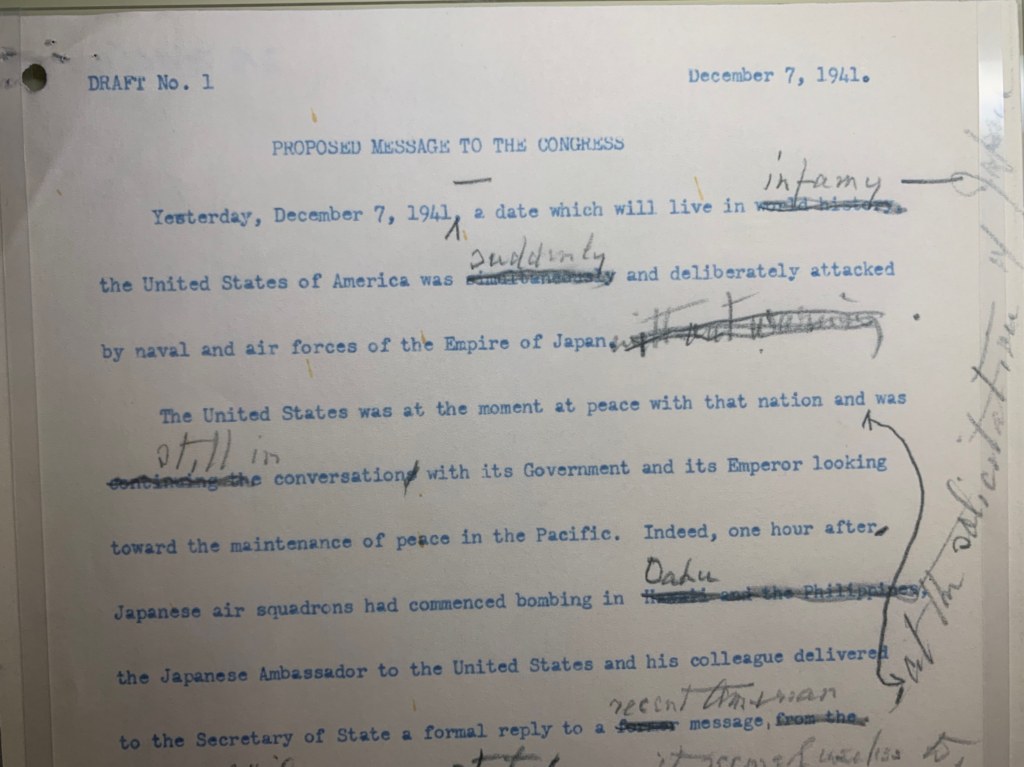

For years, the contest was dominated by Takeru Kobayashi, a Japanese legend who broke record after record, winning from 2001 to 2006. But the food tsunami hasn’t participated since 2009, since he refuses to sign an exclusive contract with Major League Eating. Indeed, the depraved tidal wave was arrested in 2010 when he jumped onto the stage after the contest. Meanwhile, Kobayashi’s arch-rival, Joey Chestnut was barred from the contest in 2024 after he signed an advertising contract with Impossible Foods, which sells plant-based hot dogs. Chestnut still holds the world record for downing a stomach-exploding 76 hot dogs in 10 minutes; but in his absence, Patrick “Deep Dish” Bertoletti took home the 2024 Mustard Belt with a very respectable 58 franks.

Now, I have described the subway stop, the carnival games, the rides, the history, the hot dogs (and the animal cruelty); but Coney Island is, above all, a beach. The experience of visiting Coney Island, for me, inevitably involves walking up and down the boardwalk, taking in the ambience. Indeed, the almost complete lack of shade on the boardwalk never fails to put me in a semi-sunstroked state, giving the scene a kind of mirage-like sheen.

It seems only right and natural that there should be a boardwalk and a beach at Coney Island. Yet like all good things in this world, it had to be fought for.

At the beginning of the 20th century, most of the beachfront property was in private hands, and so access to the ocean was severely restricted. Many poor New Yorkers could only look longingly at the waves through the links in a fence. It was not until 1921 that the city forcibly acquired the land facing the sea, and work began on the boardwalk the following year. It was named in honor of Edward J. Riegelmann, the Brooklyn borough president, who was in charge of the project. He himself opposed the name, preferring the simple “Coney Island Boardwalk,” but his contemporaries were so grateful to him that he was overruled.

Like everything else at Coney Island, the beach is wholly artificial. The beautiful white sand that covers the shore is all imported from beaches in Rockaway or New Jersey. Because the island is shielded from the waves by Breezy Point, in Queens, sand (a product of water erosion) does not naturally form here in large quantities. As recently as the 90s, the US Army Corps of Engineers was called in to add more sand to the beach—in part, to fill in the area underneath the boardwalk, which had become an impromptu shelter for the homeless, as well as a site of frequent crime.

When I was younger, a stroll along the boardwalk was akin to Dante’s voyage through hell. It was a series of activities that actively repelled me. Nowadays, I find a strange comfort in the fact that, on any given summer day, Coney Island will have the same eternal elements.

There are, of course, the thousands sunning themselves on the beach—bronzed and glistening skin, of every imaginable shade, contrasting with the gaudy colors of their swimsuits. At various points along the boardwalk, aspiring DJs have set up speakers, and are pumping out loud dance music for the passersby. Usually there are only a few actual dancers, though they flail with enough enthusiasm to make up for the lack of participants. Further down, there is the snake crew, who carry their limbless, listless reptiles on their shoulders. Presumably they make money by allowing others to pose with the snakes, though I’ve never seen any cash change hands. I have no idea how to care for a serpent; but I can’t help suspecting that so much handling isn’t good for them.

Drinking in public is illegal in the United States. Yet in the bacchanal that is Coney Island, the rules appear to be suspended. Vendors freely sell beer to pedestrians, who drink it without even the formality of a paper bag. On my last visit, a man in an electric wheelchair zoomed around yelling “Corona! Modelo!” to all and sundry. If someone took him up on the offer, he led them to a Latino man with a cooler, who presumably gives his energetic advertizer a cut of the profits.

But to be truly adventurous, one must try a nutcracker. This is a mixed drink with no set recipe, but which usually consists of vodka or tequila mixed with something sweet and fruity, like Kool-Aid. They are sold in plastic bags and drunk through a straw. There is manifestly a lot of leeway for bad actors. Some vendors may save money by watering down their drinks, and a crazy person could easily mix in poison. In my experience, however, the drinks are sugary and strong.

Strolling along the boardwalk, the visitor passes by something all too infrequent in New York City: public bathrooms. The beach is amply provided with “comfort stations,” as they are politely called, some of them quite new and futuristic. Keep going, and you pass by The First Symphony of the Sea, a wall relief by Toshio Sasaki, created to adorn the wall outside the Aquarium. Further down, you leave Coney Island behind completely. The crowds thin out, and there is hardly anyone on the sand. This is Brighton Beach, the tranquil neighbor of Coney Island. It is notable for being the city’s Russian neighborhood. There are several boardwalk restaurants where you can order borscht or pickled herring, and the shop signs are in Cyrillic script.

Turn around now and head back towards Coney Island. The tangled metal profiles of rides loom up in the distance, and the garrulous facades of amusement park eateries—selling fried chicken, hot dogs, oysters, and the like—adorn the boardwalk. Overhead, planes drag huge ads through the sky (even beaches have commercials in America), and the crowds become thick and noisy. Finally, the towering Parachute Jump appears, and next to it the great pier jutting out into the water. Nearby is a large stadium. You have finally arrived at Maimonides Park.

Opened in 2001, this is the most recent addition to the variety of entertainment options available at Coney Island. And it is perfect. Now, the visitor can spend the day sunbathing, eat a hot dog and chase it with a beach beer, ride a roller coaster and win a stuffed animal at the Whac-A-Mole, and then complete the evening with a baseball game. It is America at its finest.

(The historically astute reader may find it curious that a baseball stadium in Brooklyn is named after a medieval Jewish philosopher who lived on the Iberian Peninsula. This is simply due to its being sponsored by the Maimonides Medical Center, a non-sectarian hospital with Jewish roots.)

Maimonides Park is the home of the Brooklyn Cyclones, a minor-league team. You see, each team in Major League Baseball has what are called “farm teams,” where young talent is trained and cultivated. The Cyclones is the farm team of the New York Mets—one of several, actually—whose players earn a small fraction of the money of their major league colleagues, living in the hopes of advancement. As a result, tickets to see the Cyclones are also a small fraction of the price of major league tickets. The last time I went, I paid a bit more than twenty dollars.

The biggest night in Maimonides Park is, by all accounts, Seinfeld Night. It has become an informal holiday. This is the only day of the season when all 7,000 seats of the stadium sell out, as fans line up for a chance to get a Seinfeld bobblehead (usually of George Costanza). The Cyclones go up against their arch-rival, the Hudson Valley Renegades (a farm team for the yankees), and even become, temporarily, another team entirely: the Bubble Boys. Obscure Seinfeld references abound, as show-themes contests are held between innings, and even a few minor actors from the show make guest appearances.

When I last went, the Cyclones—sorry, the Bubbles Boys—lost 0-3 in a rather disappointing game. But the real event began after the game ended: the Dance Like Elaine Contest. For those who haven’t seen the show (and I should shamefacedly admit that this includes me), this is a dance modeled on Elaine’s spasmodic dance moves, famously described by George as “A full-body dry-heave set to music.” Dozens of people dress up in Elaine’s boxy eighties outfits and dance with arhythmic vehemence, as the crowd votes through their cheers. This year, a young woman from Brooklyn, Shannon, took home the gold with a convincingly convulsive performance.

After the contest ended, and we poured out onto the street, I couldn’t help but feel a bit wistful. Coney Island has become an integral part of my summers, something that marks a time of total freedom. More than that, Coney Island is a living embodiment of the carnival spirit, a place where traditional values are suspended or inverted, where any notion of refinement, decorum, or even of a healthy diet do not apply. Indeed, this is partly why Coney Island has had so many enemies throughout the years, from Robert Moses, to Fred Trump, and even to an immature Roy Lotz. It has been attacked as crass, neglected as unimportant, and continually assayed by businessmen trying to privatize sun, sand, and waves.

But one way to judge a thing is by its enemies. By that standard, Coney Island is one of the treasures of New York City—a monument to the prospect that everyone should be able to have a little fun.