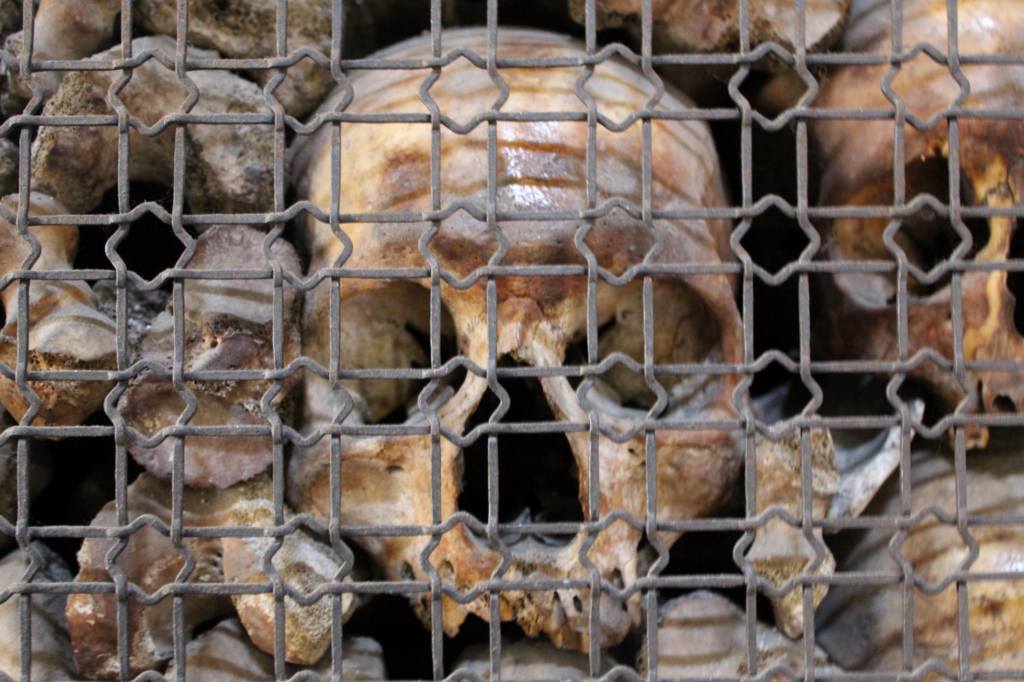

Death is unsanitary. Yet it was not until the nineteenth century that urban planners in Europe and the United States connected overstuffed cemeteries with public health. For centuries, the same small church burying grounds of the inner cities had been used for the local dead. Bodies were buried upon bodies, until the ground was piled high above street level, and a good rainstorm would leave rotting limbs exposed. One can only imagine the stench.

It was clear that something had to be done. Carlos III of Spain, for example—a relatively “enlightened” monarch—wanted the cemeteries transferred to the outskirts of Madrid. Yet this policy conflicted with the practice of the Catholic church, in which parishioners were tended to by their local priests and buried in the corresponding consecrated ground. It took the violent arrival of José Bonaparte to the throne of Spain to overcome the resistance of the clergy and establish the first cemeteries on the outskirts of the city, just as Napoleon himself was responsible for the construction of Père Lachaise in the outskirts of Paris.

The most beautiful of these far-flung cemeteries is, undoubtedly, that of San Isidro. Well, I ought to give its full, official title: El Cementerio de la Pontificia y Real Archicofradía Sacramental de San Pedro, San Andrés, San Isidro y la Purísima Concepción.

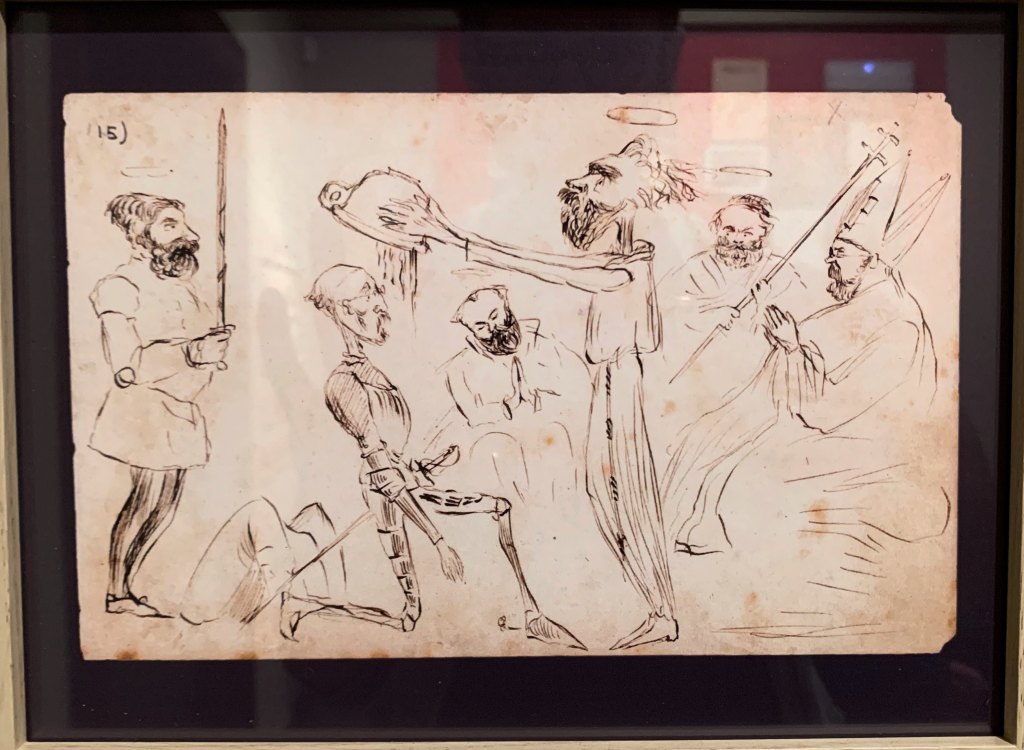

This snappily named cemetery is located on the far side of the Manzanares River, between the Toledo and the Segovia Bridges, in what used to be a remote area. Indeed, there is a famous cartoon (a design for a tapestry) by Goya, La pradera de San Isidro, which shows almost the exact same area where the cemetery stands now. It was painted in 1788, just 23 years before the cemetery was opened, and the area was visibly absent of any human construction. Of course, the ever-growing city of Madrid has since swallowed up the cemetery in its greedy embrace. Even so, the place is not exactly easy to get to, at least on public transportation. It does not help that it is only open until 2 pm.

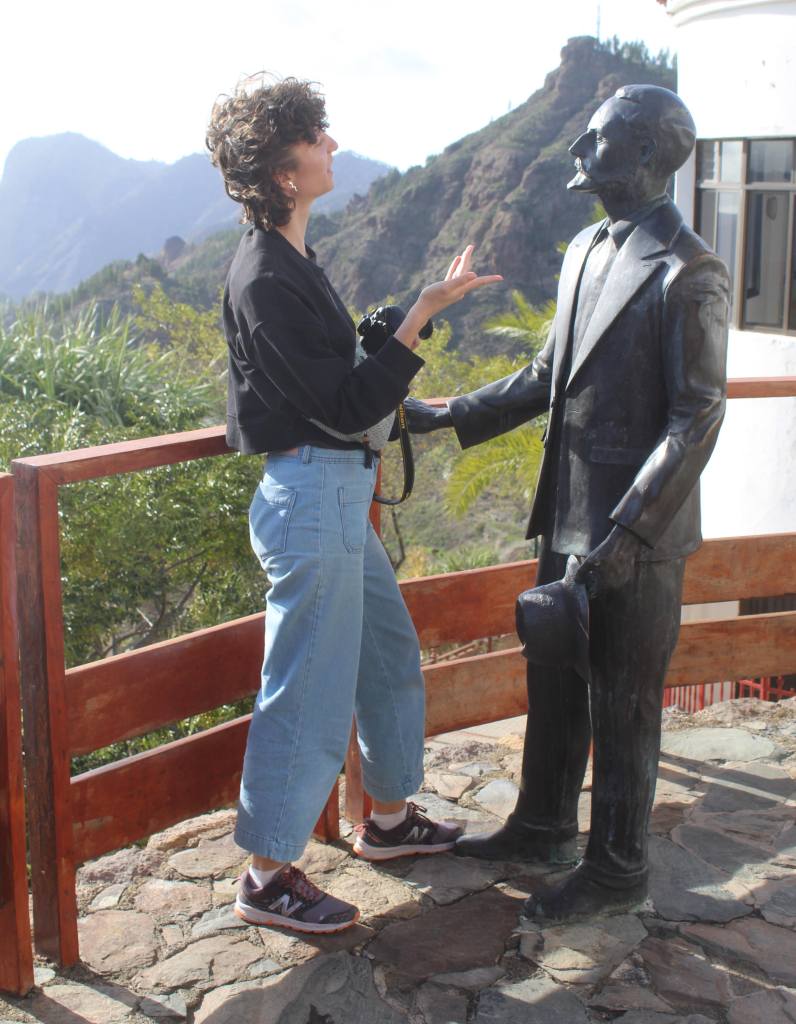

The cemetery takes its name from the patron saint of Madrid, San Isidro Labrador. (“Labrar” means to till the soil, as he was a poor farmer in life.) Isidro lived in Madrid almost 1,000 years ago, when it was a small town of little importance. Last year, 2022, marked the centenary of this saint’s canonization, and thus it was deemed a year of special celebration. But regardless of the year, every May 15th the adjacent San Isidro park fills up with revelers as a celebration of the saint’s day.

As with many catholic saints, a variety of miracle stories are told about San Isidro, one of which is that of a fountain he created by striking his staff on the ground, in order to slake his master’s thirst. This miraculous spring quickly became known for its curative properties, and it still occupies a place of honor in the cemetery.

Times have changed somewhat. To accommodate the pandemic, a motion-sensor has been added to make the fountain more sanitary. Thus, one can partake of the miraculous healing water without touching any germs. The fountain itself, though not large, is interesting for the long inscription that covers the wall. This text boasts, among much else, of having cured various types of fevers, urinary and kidney problems, erysipelas (a bacterial infection), vomiting, sores, leprosy, wounds, and even of restoring a blind person to sight. An impressive record, indeed—though I think I will stick with my current physician. Yet the fountain’s longevity is palpable, considering that it also bears an inscription of a short poem by Lope de Vega (1562 – 1635) praising the water’s power.

This fountain is right next to the Chapel of San Isidro. This is no coincidence, as the chapel was built on this spot in the 16th century on the orders of the Empress Isabel of Portugal, who believed that the blessed waters had cured her son, the future Felipe II. (This did not prevent poor Felipe from developing severe gout later in life.) Though a chapel has been here on this spot a long while, its current form is from the 18th century, when it was rebuilt. Thus, when Goya painted the chapel in 1788 (in another sketch for a tapestry, on display at the Prado), it looked very much as it does today. Even so, this is something of an illusion, as the chapel was—like much else in Madrid—totally destroyed during the Civil War, and only reconstructed to appear as it did in Goya’s day.

This quiet, peaceful cemetery was in the news last year as the site of a fascist demonstration. About two hundred Falangists (the Spanish fascist party) gathered to protest, hold up signs, and wave the Nazi salute. This was occasioned by the re-interment of the remains of one José Antonio Primo de Rivera (1903 – 1936), the founder of the Falangist party.

Ironically, Primo de Rivera became more important in death than he had ever been during his short political career. The Falangists were never a major electoral force during the Second Republic, and José Antonio did not help plan or execute the military coup which eventually resulted in Franco’s dictatorship. Rather, he became something of a martyr when he was imprisoned and then executed by the Republicans during the first year of the Civil War. After Franco emerged victorious, he found it convenient to treat Primo de Rivera as a kind of John the Baptist to his Messiah, and had Primo de Rivera’s body transported from Alicante to Madrid in a massive funeral parade.

After this, Primo de Rivera was temporarily laid to rest under the altar in El Escorial. But when Franco’s enormous symbol of fascist power—The Valley of the Fallen—was completed in 1959, Franco had the body moved once again, to serve as the symbolic centerpiece to his monument to the Civil War dead. For decades, Primo de Rivera slumbered underneath the mosaic dome of the underground basilica, directly opposite Francisco Franco’s own body.

Yet having such ghastly figures entombed in such a place of honor naturally bothered a lot of people, for the same reason that having statues of Confederate generals disturbs many Americans. The Valley of the Fallen was argued over for years until, in 2019, Franco’s body was dug up and moved to a cemetery in El Pardo. In 2023, the job was finished when Primo de Rivera’s body was also removed (the third time this embattled body has been re-buried, if you’re counting). Indeed, the official name of the site is no longer the Valley of the Fallen, but the Valley of Cuelgamuros.

Such is the hold of fascist propaganda on people’s minds that, decades after the fall of Franco’s dictatorship, and nearly a century after Primo de Rivera’s death, people still showed up to protest for the sake of these old bones.

Enough politics! It is finally time to enter the cemetery itself. As the map by the entrance informs us, the cemetery is divided into several “patios.” The first three are located on a level with the chapel and are rather like church cloisters, without much decoration. The most interesting part of the cemetery is, without doubt, the large, semi-circular fourth patio.

A walkway, lined with cypress trees—the traditional tree of mourning—leads up a hill to the upper level. It is obvious at a glance that this used to be a very fashionable place to decompose. The place is covered in elaborate tombs, mausoleums, and monuments—clearly not a burying ground for the penny-pinched. Look behind you, and you can see part of the reason for its popularity: The views of the city are quite wonderful from here (presumably why it was popular for picnics back in Goya’s day).

There are many eye-catching sculptures on display. But the first I want to discuss is a rather puzzling monument.

In a previous post, I explored the often-overlooked Pantheon of Illustrious Men, located near Atocha. The Cemetery of San Isidro has what can only be described as an aborted first attempt at that same monument. Also called the Pantheon of Illustrious Men, it consists of a tall stone pillar, upon which an angel stands with his trumpet. At the bottom of this column there is an ornate base with carved reliefs of the extremely distinguished bodies which rest beneath it. Three of these four are people the reader is unlikely to have heard of (illustriousness notwithstanding), but the fourth is none other than Francisco Goya, a person who is famous indeed.

The painter’s posthumous presence here is puzzling for two reasons. For one, this monument was not completed until 1886, while Goya died almost sixty years before that, in 1828. Second, I happen to know that Goya is certainly buried in a different chapel, not far off, called San Antonio de la Florida.

This mystery has a clear—if not exactly a logical—explanation. Goya was first buried in Bordeaux, France, where he died in exile. His body rested there, unharassed, for several decades until it was chanced upon by the Spanish diplomat to France, whose wife was coincidentally buried in the same cemetery. Obviously, the glorious Aragonese painter could not be left to decay on foreign soil, so he was relocated to his native land, and taken to this cemetery. However, because of all the bureaucratic hassle of transporting a body, Goya’s bones did not arrive until 1899, by which time the original idea of the Pantheon had lost its luster. Thus, he was instead buried in the aforementioned chapel of San Antonio de la Florida, which he had decorated with his own hand.

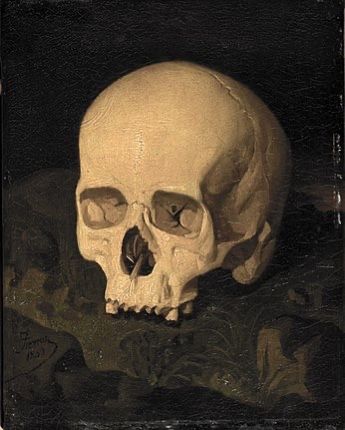

(To make the matter even more confusing, this chapel was eventually deconsecrated and turned into a museum, while an identical chapel was built just across the street—to the delight of many potential visitors, I am sure. And, to top it all off, Goya’s skull was lost at some point during this process, never to be found again. To add to the mystery, there is a painting in the Museum of Zaragoza of what is supposed to be Goya’s skull, made in the year 1849, before any of this tomb switching went on. It is possible it was stolen by curious admirers.)

We have spent a lot of time on this odd cenotaph, but there is a great deal more to see in the cemetery. Indeed, I have seen enough cemeteries so that I can confidently proclaim that the Cementerio de San Isidro is among the most beautiful in Spain—perhaps in all of Europe. The finest artists and sculptors of the time were hired to turn a place of mourning into a wonderful open-air gallery. Of course, this was not an act of public service. This was done to preserve and glorify the names of the rich and famous—who wanted their final resting places to reflect the splendor of their lives.

It would be impossible to review every notable tomb and name in the cemetery. The following is only a brief sampling of what you may find there.

By the standards of the cemetery, a relatively modest grave belongs to Cristobal Oudrid, an important composer of zarzuelas (the distinctively Spanish version of light opera). His mustachioed face, carved into the stone, keeps watch over his earthly remains. Not far off is the resting place of Consuelo Vello Cano, better known by her stage name Fornarina. She performed a genre of song called cuplé, considered somewhat risquée, which was normally sung by women (or men in drag) for an all-male audience. Her grave is presided over by the torso and wings of an angel. An extremely modest grave belongs to Ventura de la Vega, an Argentinian playwright who lived and worked in 19th century Spain. He is buried in a niche in the encircling walls of the patio.

But what naturally attracts the casual visitor are the big tombs. Perhaps the most eye-catching is the Panteón Guirao, a massive sculptural tour de force by Augustín Querol. Querol is also responsible for a monumental tomb in the Panteón de Hombres Ilustres in Atocha, and this work displays his ability to create dramatic, fluid, and even ghostly textures out of hard stone. This tomb—which occupies the center of the patio—was made at the behest of Luis Federico Guirao Girada, who was a lawyer and a politician during his life, but who is now principally remembered for his photography.

An extraordinary tomb is that which belongs to the Marquis of Amboage, an aristocratic family. This is an enormous neo-gothic chapel, bristling with prongs and complete with a metal spire, much like that of Notre-Dame de Paris. It could be a church if it did not have permanent tenants. But my favorite tomb is that of Francisco Godia Petriz. Petriz had a successful import-export business but was also an avid art collector. His mausoleum is unlike any I have ever seen. A stone sarcophagus hangs suspended by heavy chains from a large rectangular frame. The frames are held by miniature angels, who are ready to literally and figuratively carry the dead businessman up to heaven. Even if it is a bit tacky, I think the design is so original that I am surprised its architect, José Manuel Marañon Richi, is not better known.

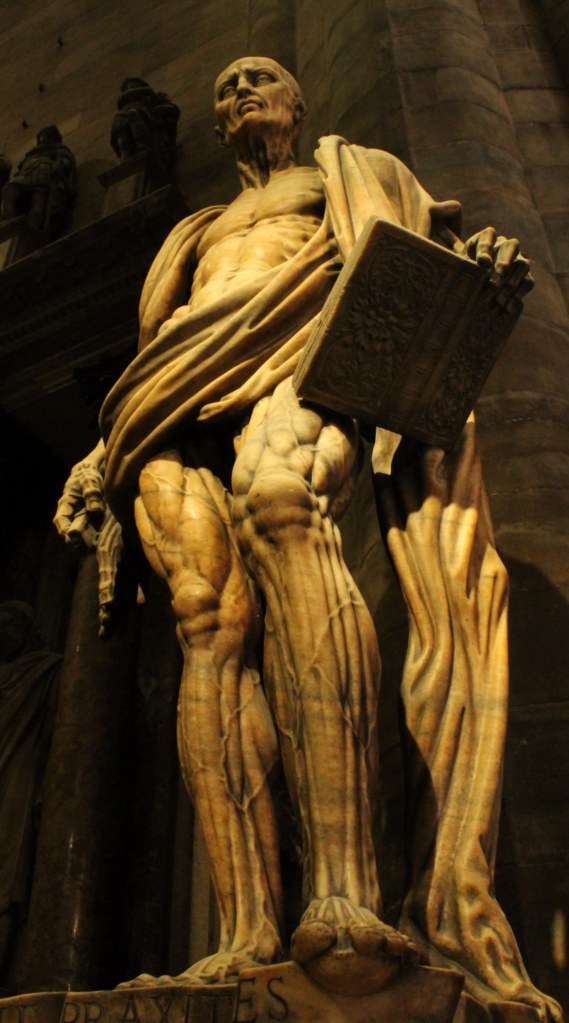

Some of the jewels of the cemetery are only available for those taking the official guided tour. These are offered only every so often and are all in Spanish. If you do manage to get one, however (they are reserved by emailing the cemetery), then you may be taken inside some of these impressive tombs. In the tomb of the Dukes of Denia, for example, there are two statues by the Spanish sculptor Mariano Benlliure, who vividly depicts the Duke and Duchess lying in deathly repose. Even more stunning is what awaits the visitor of the tomb of the Marquis of la Gándara. Inside, sitting atop a sarcophagus, is an angel wistfully looking into the beyond. This is a work of the Italian sculptor Giulio Monteverde, and it is quite wonderful. Standing in front of this heavenly being, it is easy to forget that she is made of inanimate rock, so subtly lifelike is the work in every detail.

If I am dwelling on this cemetery for so long, it is because it was a revelation to me that such a beautiful place was to be found in the city, virtually overlooked as a tourist destination. If Pére Lachaise Cemetery deserves to be on every Parisian tourist’s itinerary, then the Cementerio de San Isidro merits the same—both as an important link to Madrid’s history, and a place beautiful in itself.