In 1492, Christopher Columbus set out from Spain to find a shorter route to Asia. Europeans knew very little about the Far East at that time; but they did know, albeit vaguely, that Asia was where spices grew. Though it is difficult to imagine nowadays, cinnamon, nutmeg, and cloves were more valuable than gold. Anyone who could find a way to get them directly from the source, avoiding all the intermediary merchants, would stand to make a fortune. This is what motivated Columbus’s journey.

Of course, he did not arrive in Asia and did not find cinnamon, nutmeg, or cloves. The only spice his party did stumble upon was allspice, in Jamaica, which tasted vaguely like a blend of all three (thus the name). But the Spaniards who arrived in the so-called New World were introduced to a product that, in the present day, seems infinitely more important: hot chili peppers.

So the rest of the world was introduced to real, proper spice. To a remarkable extent, however, Spanish cuisine remains free of the influence of its former colonies. Hundreds of years of conquest, colonization, and commerce were not enough to convince the Spanish to find a use for chilis, and their food remains almost entirely picante-free.

Judging from my own experience, there is still a deep-rooted hostility to spice in Spain. I have been solemnly assured by many Spaniards that my hot sauce habit will inevitably result in stomach ulcers, if not full-blown cancer. They look on in alarm as I douse the food at the school cafeteria in my personal bottle of Tabasco, day after day. “On everything?” they ask me, dismayed. “Every day?”

Considering this, it appears to be a minor miracle that Adam Mayo has a stand in the Mercado de San Fernando dedicated to nothing but artisanal hot sauces—and properly spicy ones, too.

The Mercado de San Fernando, in the busy barrio of Lavapiés, is an excellent example of a municipal market. In its cavernous interior, green grocers, fishmongers, and butchers sell fresh foodstuffs, and an array of bars and restaurants cater to the greedy public. Like so many Spanish markets, it is a hub of the neighborhood. Regulars play dominoes and chat with bartenders, while children play tag in the labyrinthine space. On my last visit, a group of amateur musicians had set up and were playing through their set list—not for the public, but just for fun.

One of my favorite spots in this market is Mi Casita. This is a food stand run by Julián, who makes food from his native Colombia. The bulk of his business is selling empanadas—Colombian style, with beef and potato on the inside of a soft corn masa. They are cheap, filling, and delicious. Julian has been living in Spain for 24 years. Originally from Bogotá, he studied business administration, specializing in hospitality and tourism; but like many immigrants, he ended up overqualified for the job he ended up doing in his new home.

While I was chatting with Julián, a security guard, Fernanda, said hello as she made her rounds. Also a fan of Julián’s empanadas, Fernanda hails from Ecuador, and has worked in the market for the past nine years. When I asked her about the relationships between the different workers, she replied that “it’s like a community of neighbors.”

For his part, Adam, the chili sauce vendor, was drafted to dress up as Santa for the market’s holiday celebrations. “It wasn’t very good for business,” he said, “but it was fun.”

The path from a London boyhood to hot sauce vendor in the Spanish capital wasn’t exactly straightforward. Adam’s interest in chili was actually sparked on a holiday in Belize, where he tried the legendary sauce made by Marie Sharp’s. All these years later, the astoundingly smoky sauce made by this women-owned Belizean company is still Adam’s best-selling product.

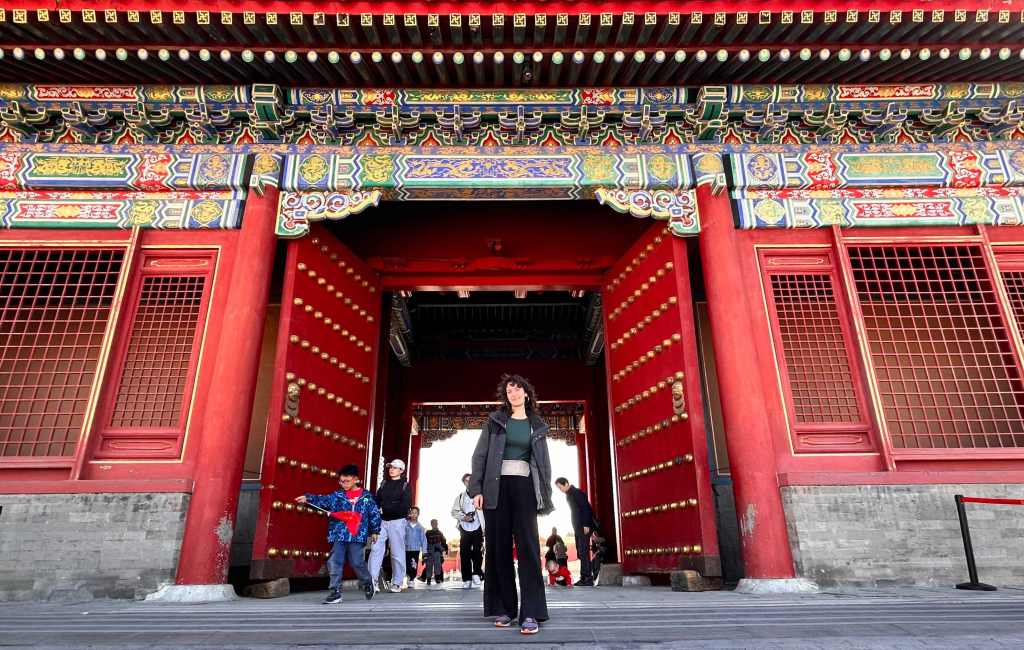

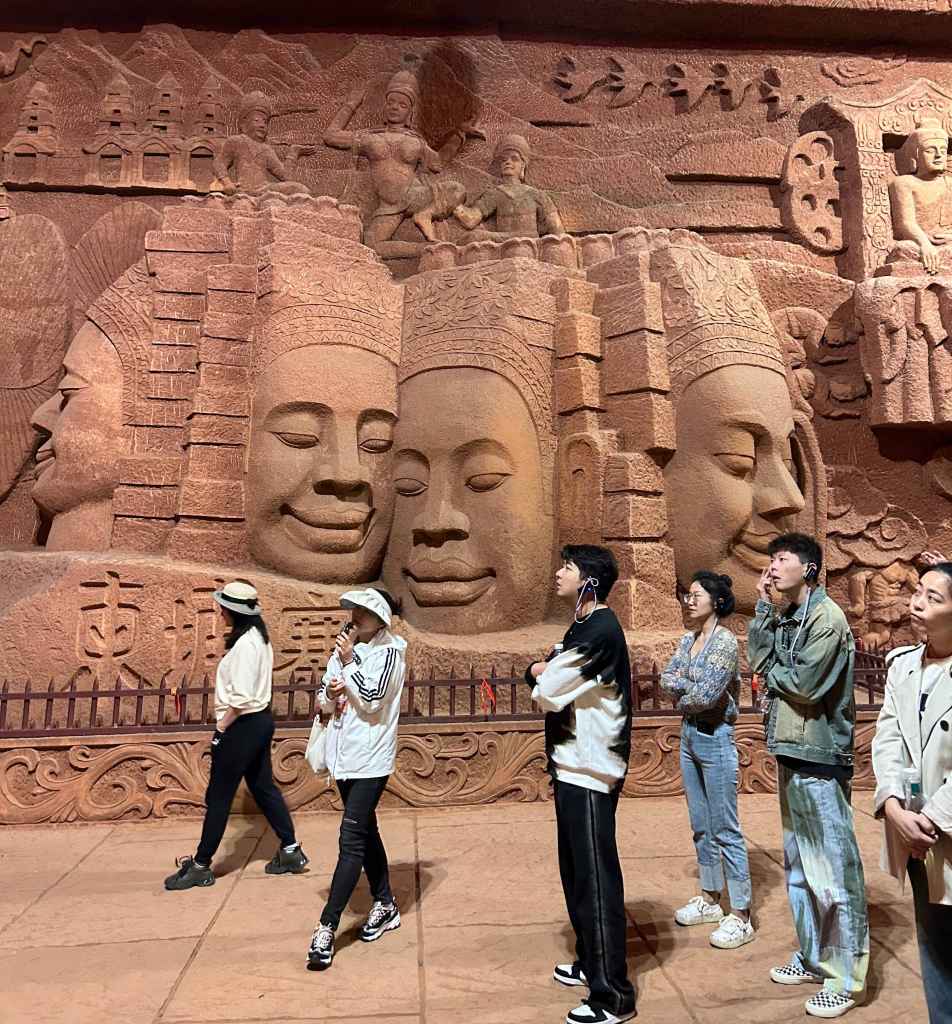

Yet much of Adam’s personal and professional life has been focused, not in Latin America or Spain, but further east: in China. He has several degrees in Chinese history and spent many years studying the language at the Escuela Oficial de Idiomas (Spain’s public language academy). Even more impressive, he traveled extensively in the country—not only to its most famous attractions, but all over, visiting rural regions seldom seen by outsiders. All of this is documented in his wonderful blog, holachina.com, which is worth perusing for the photos alone.

One would think that a man who, unlike Columbus, actually reached the far east would be possessed of a singular determination. But Adam is the picture of calm and he sits on a stool beside his table of red bottles, seemingly unconcerned whether anyone buys his wares or not. He is a master of the soft sell, letting the sauces speak for themselves. “The most important part of selling hot sauce is letting customers taste it,” he says. “And of course you’ve got to start mild and then get hotter.”

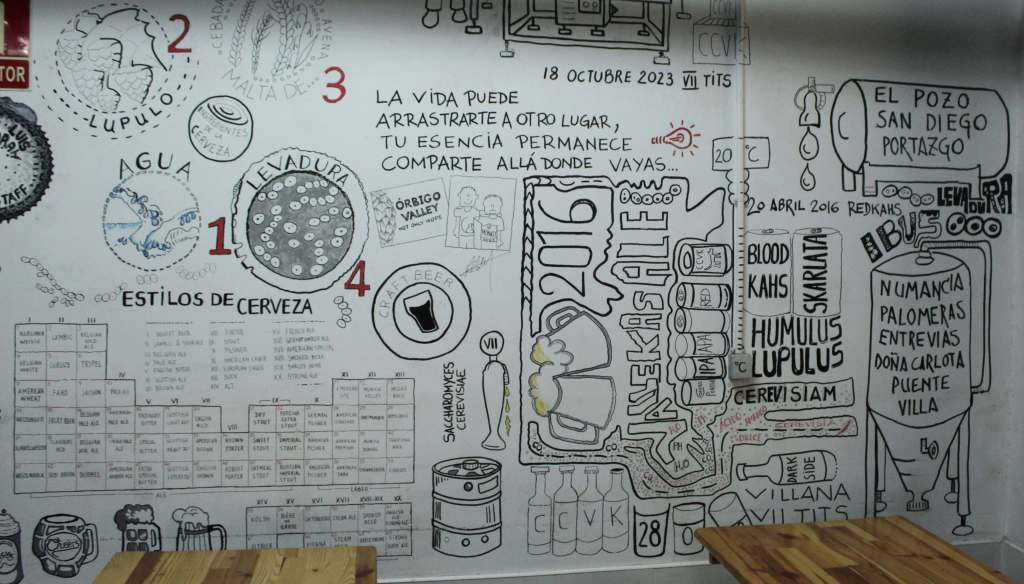

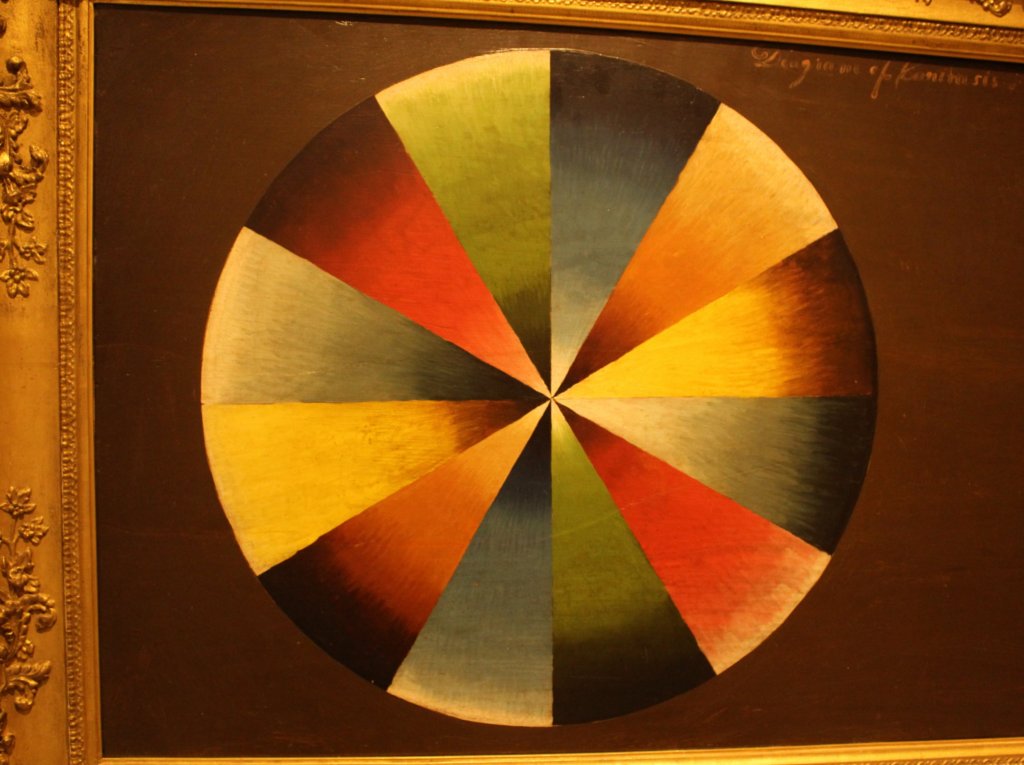

Now, to the uninitiated, the idea of artisanal hot sauces might seem absurd. Aren’t they all the same? A few minutes at Adam’s Chilli Academy dispels one of that notion. Just as beers are measured with IBU (international bitterness units), hot sauces are measured in Scovilles, which indicates the level of capsaicin in the product. And capsaicin is what makes spicy food spicy. While a jalapeño might get to a few thousand on the Scoville scale, superhot varieties like Ghost peppers, Naga Vipers, or Carolina Reapers can top one million. It is the difference between a tickle on your tongue and a trip to the emergency room.

Yet heat is just one aspect of a good sauce. Some sauces are fermented, and have that characteristic pickled flavor. Vinegar is commonly added, such as in Tabasco, giving the sauces an additional pungency. But anything can be put into a sauce: from common additions like carrots and onions, to more exotic ingredients like mangos and bananas, to offbeat flavors like maple syrup or horseradish. The varieties are really endless, which is why people can become obsessed with it. Adam has clearly fallen down this rabbit hole, as he rummages through his collection of bottles like an alchemist, displaying his encyclopedic knowledge.

It is one thing to have a store, however, and another thing to make a sale. Are people actually buying? “Oh yes,” he says. “Business is swift.” And according to Adam, 80% of his clients are Spaniards. This would seem to indicate a change in attitude. “A lot of young people are interested in hot sauce,” he explains. “They see it on Hot Ones.” If you don’t know, this is a YouTube talk show, wherein celebrities answer questions while trying increasingly spicy hot wings. The show has proven to be such a hit that there are various spinoffs, such as the Spanish version A las Bravas, which uses potatoes rather than chicken wings.

Adam isn’t the only one who believes in the future of hot sauce in Spain. This article was kicked off by a message I received on this blog from a man named Mark, another Londoner in the chili business. He invited me to come see him in the Mercado de Motores, and I agreed.

In addition to the municipal markets which dot Spanish neighborhoods, there are many temporary markets that are set up on weekends all around the city. The Mercado de Motores is one of the biggest and the best. It takes place every other weekend in the Museo Ferrocarril, or Railway Museum—a collection of antique trains in the old Delicias station that is worth visiting in any case. During the market, vendors selling everything from scarves to earrings to handmade jewelry set up inside the old station, while food trucks dish out burgers and tacos outside.

On my way to see Mark, I was stopped in my tracks by a familiar face. The previous spring, I had gone on a trip to Galicia with my mom; and in a little town overlooking the Cañon de Sil we stumbled across a stand where a man was selling artisanal honey. This was the man I encountered now, several hundred kilometers to the south, with the same spread of honeys before him. His name is Óscar, and he is one of the owners of Sovoral. I stopped to have a chat.

Óscar informed me that he got into the honey business through his wife, who comes from a family of beekeepers. Before that, he was a truck driver. Óscar does much of the beekeeping himself now, despite having an allergy to bee stings. “Doesn’t it scare you?” I asked. “No,” he said, shrugging stoically. “Like anything, you get used to it.” Though I love honey, I was more interested in another of his products, a hot sauce made from pimientos de padrón (a Galician variety of pepper), sherry vinegar, and (of course) honey. It is sold in a beautiful, long-necked bottle and has a surprising flavor. It is not just foreigners, then, who are in the hot sauce business.

Mark’s stand was just further down. Though I arrived at a less-busy time of day, between the midday and afternoon rushes, Mark was still mobbed with customers. Like Adam, he realizes the importance of letting customers try his products. On the left were crackers with cream cheese, ready to be anointed with one of his four styles of chutney. On the right, corn chips were similarly prepared, ready to be covered in one of his four hot sauces.

Mark’s life before becoming the Sauce Man (his brand name) was just as meandering as Adam’s. He worked in a PR company, and as a DJ, and for a long time in the British consulate, helping befuddled countrymen sort out legal problems.

Mark is energetic. Whether in Spanish or English, his speech is rapid fire. As he works, he is in constant motion. If Adam prefers to let the sauces do the talking, Mark fills up the air around him, seeming to grab every passerby and pull them in. And his approach was working, as I could hardly get a word in amid the constant flow of customers.

Catering to the Spanish market, Mark decided not to go in for intense heat. Many of his chutneys are not spicy at all (though they’re quite good), and even his hottest sauce won’t burn your tongue off. Even so, he is quite convinced that hot sauces have a bright future in Spain. “You and me, we have an advantage,” he explained. “Where do food trends come from? Your country. Then they get to the UK, and finally filter into Europe. It’s like craft beer.”

Judging from his success, he seems to be right. Somehow, while three hundred years of colonizing Mexico were not enough to develop a taste for chili peppers in Spain, just a few decades of exposure to American culture have done the trick. When I ran into Mark the following weekend, at the Mercado Planetario near my apartment, he was similarly deluged with customers—and all of them locals.

Mark very kindly invited me to his kitchen in Vallecas, where he personally makes all of his sauces by hand, with only occasional help. I arrived one afternoon, while Mark was putting the finishing touches on one of his chutneys. “When I’m in production, I work 12-hour days,” he said, pouring sugar into the boiling pot. “Don’t you get tired?” I asked. “Not really. When you’re your own boss, it doesn’t really feel like work.”

But it did look like work, as he peeled and diced onions, blitzed garlic and ginger into a paste, and chopped up pineapples. The striking thing about his process was how uncomplicated it seemed. And I suppose a hot sauce is a simple foodstuff, at least in concept: get some chilis together with a few other ingredients, and blend it all up. The key is finding the right balance of flavor and, crucially, the right consistency—neither gloopy nor runny. How does Mark do it? “I don’t use xanthan gum,” he said, “which is what’s normally used to give it viscosity. I have my own way, but it’s a secret.”

Both Mark and Adam would qualify as small-business owners. Thanks to Adam, however, I got a chance to talk to somebody who produces hot sauce on an industrial scale.

Carlos Carvajal is Spanish-American—with a Granadina mother and an American father. Born in Spain, he grew up in California. There, as a young man, he met a Jamaican man named Joel, who introduced him to the magic of jerk sauce. Carlos himself learned the recipe and, in 1994, opened a hot sauced company with another friend called Slow Jerk. The company was relatively small and they eventually sold it, but it was a beginning.

Now, he is the founder and part-owner of Salsas y Especias Sierra Nevada, which sells hot sauces under the brand Doctor Salsa. In just over a decade, his company has grown into a veritable empire of picante, selling chutneys, seasoning mixes, spicy chips and peanuts, and even spicy honey, in addition to his hot sauces. Most dangerously, you can order pure capsaicin extract from the website—aptly called “tears of the devil.” Based in the town of Ogíjares, near Granada, Carlos’s company now sells sauces throughout the country and beyond, exporting them around Europe.

During our phone conversation, I asked Carlos something that I had also asked Adam and Mark: “Is hot sauce a way of life?” A silly question, sure; but there does seem to be something that unites chiliheads together. In Carlos’s case, he is a blackbelt in several martial arts, and in his free time likes to drive high-powered cars. Adam, as we saw, is a world traveler, while Mark spends his scant free time, not relaxing, but playing golf and tennis. If anything unites lovers of spice, I would posit that it is a certain restlessness: a dissatisfaction with the ordinary, a need to take things to the next level. Why else would they need to make their food painful?

And this brings me back to an earlier question. Is hot sauce unhealthy? The answer seems to be a qualified no. Rather than causing stomach ulcers, hot sauce may actually help prevent them—though it can aggravate any ulcers already formed. Chilis are extremely high in Vitamin C, but only a few drops of hot sauce won’t contribute much to your diet. It’s possible that capsaicin has some health benefits, though the evidence is unclear. According to this article, however, if you ingested too much capsaicin it could actually be fatal; but you’d have to eat 2% of your weight in superhot peppers—an unlikely scenario. For most people, then, the quantity of sauce they consume probably proves to be nutritionally insignificant.

This may sound like a letdown, but I find it liberating. As Carlos pointed out to me, just a few drops of a sauce can change the flavor of an entire dish—adding a new element to it—without altering its nutrition. A simple dish of, say, rice and beans can be turned into a memorable meal with the shake of a bottle. So I think I will continue my Tabasco habit at the school cafeteria.