“Dublin is fine, I guess. But you gotta see Galway. It’s incredible.”

My friend Durso had told me this on my first trip to Ireland, launching into a long glowing description of the coastal city. Now, six years later, it was my chance to finally see this mythical place. How would it measure up?

By the time we arrived—after a long day of driving—it was already evening. We headed into the center of town without a plan or even knowing what to expect. All I knew was that Galway was supposed to be nice.

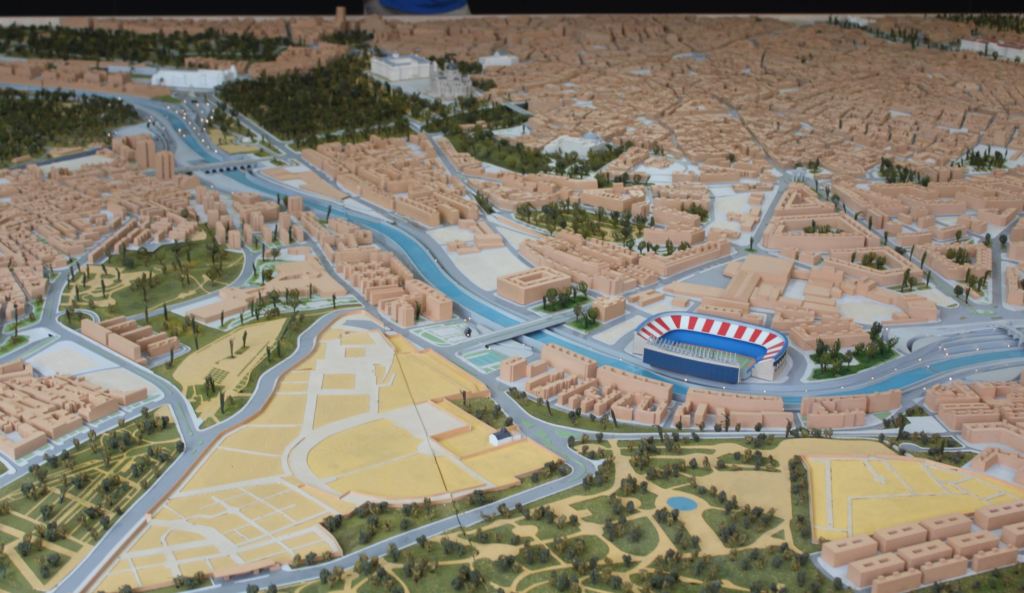

Galway, a medium-sized city, is situated on the western coast, almost directly across from Dublin. The city was once an important port for commerce and fishing. Nowadays, its economy has two new pillars: tourism and education. The latter is especially important. Of the roughly 85,000 residents of the city, nearly a quarter are students at the University of Galway. For a place with so much history, it has a very young population.

This was immediately apparent to us. As it happened, the day we arrived was Freshers’ Day, when all of the first-year students are welcomed to campus. A parade of young people marched down High Street, all of them looking lost and amazed—overwhelmed by their new-found independence. And, crucially, unlike in my own country, freshmen in Ireland are of drinking age. It was bound to be a wild few nights.

This youthful presence—combined with the plentiful tourists—gave the center of Galway a raucous energy. Every bar was packed, every restaurant was full, and we had to dodge between crowds and street performers. I had imagined a picturesque old fishing village, and this was a nightlife district.

But the city is well-adapted to hungry and thirsty crowds, and we soon managed to satisfy our bodily desires. After dinner, we searched for a bar that wasn’t overwhelmed by students. Eventually, we decided on Tig Cóilí, a tranquil place with classy wooden furnishings. This is one of the many whiskey bars in the city. After asking the barman for some advice, I had a glass of Micil Invernin, a single-malt whiskey with a pronounced smokey and peaty flavor—reminding me very much of Laphroaig Scotch. This was followed by a strangely delicious Irish coffee, whose mixture of alcohol and caffeine produced a strange wakeful drowsiness.

The rest of our stay in Galway consisted mainly of mornings and evenings, as we had several day trips planned. This meant that our impression of the city was inevitably skewed. Nevertheless, it is fair to say that Galway is not a city of many attractions. Though historic, only fragments of the city’s medieval past remain.

Notable among these is the so-called Spanish arch, an extension of the city walls (now mostly gone) down to the docks. There is nothing particularly Spanish about this arch. It got its name because of the many Spaniards, usually merchants, who used to visit Galway, mooring their ships near this arch.

Indeed, Christopher Columbus himself (who DNA studies reveal to have had a Spanish origin) visited Galway as a young man, and spoke of seeing “Cathays” (the antique word for Chinese people) who had arrived on logs. These people were almost certainly not Chinese, but may have been Inuits who were blown across the Atlantic in a canoe. Nevertheless, it reinforced his belief that a voyage to Asia was possible by sailing west.

All of this history was unfathomable, however, as we wove our way through the young crowds. Galway is certainly not a city oriented towards the past. Indeed, for a place with such a romantic setting—the stormy Atlantic brooding in the gray distance—and with the soothing sound of water continuously nearby, Galway is a surprisingly energetic place. Perhaps it is no wonder that my friend, who visited during his drinking years, loved it so much.

I do want to single out Il Vicolo, an Italian restaurant we visited. Now, I am normally opposed to eating Italian food out unless I am traveling in Italy. It seems like a wasted opportunity to eat something available everywhere, rather than trying the local food. But in this case, the decision turned out to be a good one. The restaurant—in a historic building overlooking the river—was attractive, and the food a welcome relief from the heavy Irish fare.

Lost amid the crowds and the nightlife, I did not appreciate the impressiveness of Galway’s natural setting until it was time to leave it. On our first morning there, we boarded a bus that took us from Galway to Rossaveel. We soon left the city and were being swept along a fairly suburban area overlooking Galway Bay. The morning was gray and overcast, and the landscape had none of the usual sweetness that one associates with Ireland. Instead, it was rocky and desolate, almost reminding me of Iceland. The North Atlantic is a harsh and dramatic environment.

We were there to catch a ferry to the Aran Islands. These are a group of three islands that lie at the westernmost point of Ireland. Inishmore is the largest and most popular of these, and this was our destination. The trip lasted about an hour and deposited us in Kilronan, or Cill Rónáin (in the official Irish spelling), the only place on the island approaching a proper village. With a population of less than 300, it is home to over a third of the island’s inhabitants—which gives you some idea of its remoteness.

If Galway struck me as a place with too many people and not enough history, Inishmore was exactly the opposite. Despite the boat loads of tourists (we among them), and despite the island’s relatively small size (about half as big as Manhattan), the island creates a powerful sense of isolation in time and space. The landscape is windswept and bleak—deforested after centuries of human habitation, and littered with ruins, both old and new.

We immediately set about procuring ourselves a tour. Now, there are many options for visitors to the island. You can rent bikes and explore on your own, or even just take off walking. The most popular option, however, is to sign up for a minibus tour. There is no need to book in advance. As soon as you leave the ferry, a host of tour operators confront you, all of them offering pretty much the same tour at the same price. We signed up for one without any research or planning, and it ended up being fantastic.

Our guide soon whisked us into the rocky center of this island. Speaking rapid-fire into a microphone, he gave us a running commentary on everything we were driving past. And he had a lot to say. Aside from being a tour guide with ample experience, he was also a native of the island, and could frequently add a personal touch to his narrative. Now, I admit that I have forgotten the vast majority of what he said—he spoke fast, and in a thick accent—but I do remember the sense of wonder I had, as he effectively pulled us into what it was like to grow up in such a place.

I can attempt to write a description of the island here—its rugged hills of pale green, ringed by rocky shores and covered in gray ruins—but I think it would be better just to instruct any curious readers to watch the film The Banshees of Inisherin. This film—properly tragic-comic, as are so many Irish stories—was filmed here, and does a wonderful job in capturing the combination of desolate beauty and provincial isolation.

One valuable part of the experience was simply overhearing the guides speak Irish. You see, Inishmore is a Gaeltacht, which is a section officially designated as having Irish as the first language. Language has a political element here, as it does in so many other parts of the world; and adoption of Irish (also called Gaelic) as a co-official language with English was seen as an important step in the assertion of Irish identity. Nevertheless, the overwhelming majority of the population still speak English, and learn only minimal Irish in school. Inishmore is one of the few exceptions to this rule.

The high-point of the visit, literally and metaphorically, was Dún Aonghasa. This is an ancient fortress, situated high on a cliff overlooking the Atlantic. Even the approach is dramatic. Stumbling over a rough cobblestone walkway, ringed by stone fences, the visitor gets a small taste of how secure this place must have been in its time. The surrounding fields are strewn with spiky stones that would have disrupted any approaching army.

Nearer, the visitor passes through a series of four concentric walls. Even today, after years of neglect and decay, they stand far taller than a person, and are thick enough to withstand serious force. (Admittedly, major sections of the walls have been restored.) Clearly, the people who built this fortress did not want to take any chances. But who were they? Archaeologists are not entirely sure. The fortress seems to have been built sometime around 500 BCE by the Celtic inhabitants. Its name may refer to a god from Irish mythology. That is about as much as we know.

Today, it is impressive more for its setting than for anything it can tell us about prehistoric Ireland. Hanging precipitously from a cliffside, the fortress suggests a people who were surrounded by enemies, who lived with their backs to the wall. The day we visited was fairly mild. Even so, the Atlantic looked brooding and dangerous in the distance, an angry infinity waiting to swallow up this floating bit of rock. It must have been an exceptionally hard life.

The other major historical site on the island are the Seven Churches. This is a somewhat misleading name, as there are only two churches at the site, and they are both in ruins. Our guide told us that they were “early Christian” structures, though he couldn’t offer much in the way of specifics, aside from mentioning that they used to be important destinations for pilgrims. The dilapidated and unused churches are surrounded by a still-active graveyard, which gives the place a rather spooky air.

The last attraction on our tour was a small group of seals. Wildlife abounds in West Ireland—its waters home to whales and dolphins, its skies full of sea birds, and its land covered with red deer—and Inishmore is no exception to this rule. A small seal colony shares the island with its human inhabitants, and provides a whimsical sight for the tourists.

After around three hours, our guide deposited us back at Cill Rónáin, where we had some good Irish food and a few cold beers. Then, it was time for the ferry ride back to the mainland. That night in Galway, surrounded once again by the hordes of freshers, the island of Inishmore had a sort of dreamlike quality to it—a place trapped in time, preserving a piece of old Ireland so that these young people could one day, too, come to enjoy it. Now that my friend Durso is somewhat older, I’m sure that he would love it even more than he loved Galway.