One Hundred Famous Views of New York

“What kinda photos you take?”

The guy at the bagel store had noticed my camera. I was in Inwood, far uptown, waiting for my friend Greg.

“Oh, you know. A bit of everything, I guess.”

“Got any kind of social media I can follow?”

Very flattered, I typed in my Instagram on his proffered phone.

“I’m not famous or anything,” I said, and took another bite of my bagel—everything, with lox, cream cheese, and onions. A New York classic.

“I’m sure you got a lotta stories with these photos, boss,” he said, very kindly.

I tried to say “thank you” but, mid chew, only managed “thnnn ynnn.”

Greg arrived five minutes later. After ordering something for himself—“There is only one type of bagel,” he proclaimed: “everything”—we headed out. We were starting our walk to the bottom of Manhattan.

At my insistence, we had started late. I hate getting up early on the weekend, and so I set our rendezvous for 1 p.m.—which, of course, meant that we didn’t get moving until 1:30.

It was a brilliant summer day, hot but not too hot, and blessedly not humid. Our plan, if it deserved the name, was to follow Broadway all the way from the East River to The Battery. However, we also had an agreement—nearly fatal—that we would stop at anything that caught our eye. This happened almost immediately.

To our right, we noticed an old wooden house that looked jarringly out of place. A sign proclaimed it Dyckman Farm, the oldest—and possibly, the only—extant farmhouse on the island of Manhattan. Naturally, we had to visit.

The Dyckman family was of old Dutch stock, having arrived in the 1600s. During the Revolutionary War, however, they fled upstate to avoid the British occupation, returning later to find their original property destroyed. Thus, the current structure dates from around 1785.

Yet the description did not focus exclusively on this family, instead devoting ample space to the many enslaved people who worked and lived on the property, as well as the indigenous people who lived here before. “This is definitely not how it would’ve been described when we were kids,” Greg remarked, quite truly.

The visit cost us $3 and was short and sweet. Two things stick out in my memory. One was a small exhibit about the games that were played by the family, including a playable set of nine men’s morris—a board game even older than chess—with rules printed on the wall. If we had more time, we would’ve had a go. Upstairs, in the bedroom, the walls were decorated with “samplers,” which were embroidered fabrics meant to showcase the skill, class, and devotion of a young woman, in order to secure a favorable match. Tinder profiles seem more efficient, though perhaps less worthy to be deemed family heirlooms.

Yet, for me, the most startling item on display had nothing to do with the farm at all. It was a photograph of the construction of the Dyckman Street subway station, from 1905. What is striking about the image is the almost complete lack of a visible urban presence. It is a stunning reminder of how recent the city’s explosive growth has been. (The photo also intrigues for the apparently nonsensical decision to build public transit into empty land—a paradox resolved by the assurance that the land would be quickly populated once the subway was up and running.)

Our walk continued. Broadway took us alongside Fort Tryon Park, a lovely green space overlooking the Hudson River. We briefly considered visiting the Met Cloisters, which sits atop the large hill, but wisely decided it would take too much time.

Now we were in the Heights. Manhattan above Harlem hardly feels like Manhattan at all. It is another world, an outer borough. With a few exceptions, the buildings are just a few stories tall, and there are virtually no tourists to speak of. This part of town is predominantly Latino. You see just as much Spanish as English in store windows, and hear more of it spoken in the streets. Men in tank tops, sitting on folding chairs, play dominoes on the sidewalk as if it were their front lawn. At one point, we passed by a family having a full-blown cookout, with giant trays of spaghetti and rice and beans. The food looked so good that I was a millimeter away from asking for a plate—when my better judgment forced my legs to keep walking.

On any walk through Manhattan, there are some sights that are unavoidable. A fire hydrant leaking water into the streets, for example, or some pigeons having a feeding frenzy. Rats dart from beneath giant mounds of reeking garbage bags. Orange funnels in the street ooze steam into the air—a byproduct of Con Edison’s massive steam heating system belowground—and identical wooden water towers sit inexplicably above every tall building.

But perhaps the most omnipresent Manhattan sight is scaffolding. There are about 400 miles of it in New York City, on seemingly every other building. Remarking on this, Greg recommended John Wilson’s episode on scaffolding, which is a deep dive into the surprisingly strange world of pedestrian protection. I second the recommendation. But here is the short version.

In 1979, Grace Gold, a freshman student at Barnard College, was tragically killed when a piece of debris fell off a building, striking her in the head. This led her older sister, Lori, to a dogged campaign to prevent further tragedies, culminating in the passing of Local Law 11. This mandates the inspection and maintenance of the façades of buildings over six floors tall, every five years. During this work, scaffolds (also called sidewalk sheds) are put up to protect pedestrians below.

The scaffolds present a kind of obstacle course for the pedestrian. Sometimes they provide needed shade, or a place to lean and hang out; and for many New Yorkers, they become a kind of outdoor living room. They can also narrow the sidewalk and cut off pathways, creating annoying detours and bottlenecks. Businesses hate them for decreasing foot traffic, and tourists for ruining photos of iconic buildings.

This time around, it struck me how nearly all of these classic elements of the city—the garbage bags, the water towers, the steam vents, the scaffolds, and even the fire escapes—are absent from the other city I know best: Madrid. Indeed, they are absent from most other American cities, too. Yet when I lived in New York, it never even occurred to me that these features could be unique or identifying.

Now, I have created my own detour, and must return to the walk.

Our first major city landmark was the George Washington Bridge. We passed underneath the busiest bridge in the world and were immediately waylaid by some street vendors. Greg got himself a ring and an outrageous bracelet—successfully bargaining down the price—and we were off again, heading towards Harlem.

Broadway does not take you through any of the most iconic spots in Harlem, which are further east. But it does run by one of the most grandiose and least-known museums in the city: the Hispanic Society of America.

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, its name is somewhat misleading. Though it is in a “hispanic” neighborhood, the museum is mainly devoted to Spanish cultural heritage; and is not, and has never been, a learned “society.”

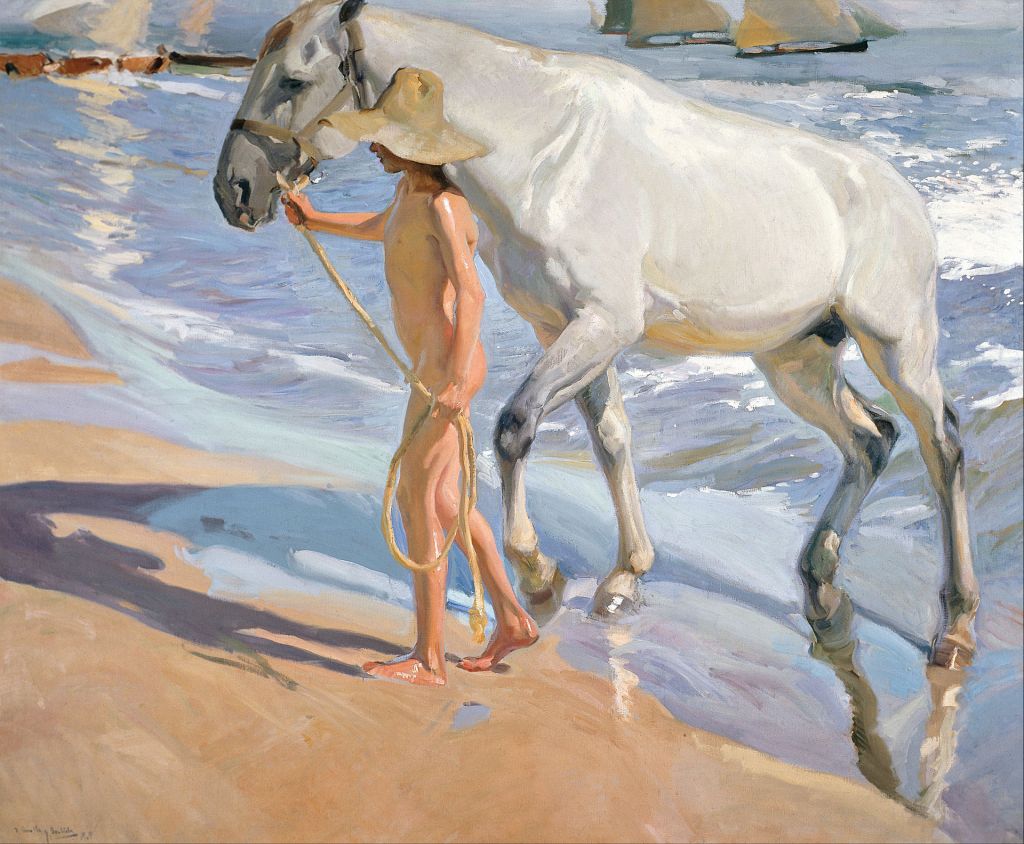

The museum is housed in Audubon Terrace, a beautiful beaux-arts complex of buildings. And though it is still not fully open after its years-long renovation, it is free to visit, and was a very pleasant place to cool off for a few minutes. For me, it is a measure of the city’s internationalism that, on top of all of the cultures and countries represented in its boroughs and neighborhoods, I can find a panoramic series of paintings depicting all of the regions of my new homeland—by one of Spain’s greatest painters.

Broadway took us within striking distance of two other Harlem landmarks—Hamilton’s Grange and City College’s magnificent neogothic campus—but we powered on, down to 125th street, where we knew a bar with an excellent happy-hour deal on wine. My brother, Jay (who had previously done this walk, and so didn’t want to subject himself to it again), would meet us there, as Greg and I tried to limit our wine intake so as not to sabotage the journey.

This is, coincidentally, one of the most picturesque stretches of Broadway. The street dips low and then rises up again, which forces the adjacent Subway Line 1 to briefly become elevated above-ground. A century ago, Manhattan actually resembled Chicago in its plethora of elevated metro lines; but most train lines have since been moved underground.

For my part, though I can understand hating the noise and resenting the obstructed views, I think there is something remarkably charming about these elevated lines. The criss-crossing steel beams, looming overhead, evoke a moment in industrial history when technology was both gritty and excitingly new. And the view from the train is certainly better. In any case, the large arch over West 125th Street is worthy of a poem.

As you get into Harlem, one sight becomes omnipresent: public housing. These mainly take the form of square, red-brick buildings, surrounded by small grassy lawns. Admittedly, most of my knowledge of these housing projects comes from reading The Power Broker, wherein Caro describes how Robert Moses destroyed old neighborhoods to make way for soulless housing that was, in many respects, worse than what it replaced. But as the city—and, especially, Manhattan—confronts an ever-worsening housing crisis, it occurs to me that we may have to give the idea of public housing another look.

At one point on the walk, the sidewalk narrowed into a kind of tunnel, due to construction on the building next door. And for whatever reason, the pavement was littered with the lifeless bodies of spotted lanternflies. This is an insect pest, originally from southeast Asia, which has spread far and wide due to human activity (they lay their eggs on pieces of wood, which then get transported). Though the insect is actually quite beautiful—with brilliant red wings and an attractive spotted pattern—and though it poses no direct threat to people, New Yorkers were encouraged to kill them on sight for the threat they pose to agriculture and the environment generally.

By now, they’ve probably multiplied to such an extent that killing them doesn’t do any good; but we still did our part and murdered the three or four remaining living insects on the sidewalk.

“It’s like a level of a video game,” Greg joked, as we exited the lanternfly tunnel.

Now we were entering the vicinity of Columbia University, whose presence stretches far beyond its main campus. One obvious sign that we were entering its orbit was the proliferation of bookstores and book stands. This was perilous for the both of us. Anyone who knows me is aware of my fondness for the written word. And Greg, well… he’s a history professor. If our odyssey was like a video game, then this level was far more challenging than the lanternflies. We had to resist the pull of knowledge.

I did, however, take the opportunity to buy Greg a book I’d been recommending him for some time: Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, by science fiction writer Samuel R. Delany.

Now, to give you some background, Rudy Giuliani’s campaign to clean up Times Square has often been celebrated as an example of successful urban redevelopment. Before Giuliani’s stint as mayor—that is, from the 1960s to the early 90s—Times Square was considered a rather seedy area, full of porn theaters, peep shows, and nightclubs. Far from a tourist attraction, it was an area most people tried to avoid. Its transformation from a symbol of the city’s decline to its star attraction is thus usually heralded as a triumph.

Delany calls into question this basic narrative, and he does so with stories of his own explorations—and sexual adventures—in the old, sordid Times Square. For a sex-positive, anti-gentrification, urban studies academic, and a proud New Yorker to boot (in other words, my friend Greg), this seemed like the perfect read.

The real highlight of this part of town was a visit to Tom’s Restaurant, the diner featured on Seinfeld. For such an iconic spot, it is wonderfully unpretentious, with reasonable prices and a classic diner atmosphere. We took the opportunity to order some milkshakes, and I heartily recommend the same to anyone in the area.

We kept going, moving out of Harlem and into the Upper West Side. This is easily one of the architectural highlights of the city, mainly due to the many ostentatious apartment hotels—the Dakota, the San Remo, the Hotel Belleclaire—that were built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, by architects such as Emery Roth. Indeed, this part of Manhattan could easily rival the heart of Paris for its elegance and beauty. Even the subway station at 72nd street is a monument. Rather than try to explain any more myself, however, I will recommend this excellent video by Architectural Digest—as well as their YouTube channel generally. It is some of the best content available about the city.

But I will pause to savor the pizza we had at one of my favorite New York spots: Freddie & Pepper’s. All of us ordered the same thing: a slice with tomato, basil, and fresh mozzarella. It was exactly what we needed to continue our walk.

Now, I would like to take a moment to consider the smells of the city. Though some, like pizza, are conspicuously good, for the most part Manhattan is malodorous: hot garbage, urine, car exhaust, bodies covered in sweat… But lately a new smell has taken over: marijuana. It is not exactly the most pleasant odor (at times it can smell remarkably like a skunk), but it is certainly omnipresent since the legalization, in 2021, of recreational cannabis.

One of the ideas behind legalization was to treat cannabis like wine or liquor, selling it at licensed stores. However, since the unlicensed distribution network was already (shall we say) quite robust, unlicensed stores and stands popped up throughout the city before the legal venues could get a foothold, much to the embarrassment of politicians. Indeed, a major government crackdown was taking place during the week of our walk, leading to the shutdown of over 750 illegal stores. Crackdowns notwithstanding, the city has certainly taken to legal weed with gusto.

The last major sight in the Upper West that we passed was Lincoln Center. We sat down to rest in the nearby Richard Tucker Park, while a bored-looking young woman sang operatic arias—quite well, really—in order to “fund her education.” Puccini and Verdi notwithstanding, I had the music of West Side Story in my head. It was here, after all, that the original movie was filmed—in the ruins of the demolished San Juan Hill neighborhood—and where the Steven Spielberg remake was set.

Robert Moses enters this story once again, as it was the notorious commissioner who spearheaded the project—seizing the land from the working-class, multi-ethnic residents of the neighborhood, and then razing the property in order to make way for the city’s new bougie performing arts center. In other words, it was yet another chapter in the long history of Manhattan’s gentrification. At least Lincoln Center looks good.

Finally, as Broadway slowly bent eastward, we hit the next major landmark on our walk: Columbus Circle. This meant that we had finally gotten below Central Park, and were officially entering Midtown Manhattan. The entrance to the park was bustling with activity, as hot dog vendors and the drivers of horse-drawn carriages and pedicabs vied for the tourist’s attention (and money). Yet what struck our collective attention was the large monument on the park’s southwest corner. We stared at it, wondering at its significance, until Jay looked it up on his phone:

“It’s a monument to the USS Maine!”

Now, you may be forgiven for not remembering the significance of this ship. This was an armored cruiser that exploded and sank in Havana’s harbor in 1898, with the loss of 268 sailors. And though the evidence that it had been deliberately attacked by the Spanish was weak at best, the ship’s sinking became a cause célèbre which led to the Spanish American War. Nowadays, neither the Maine nor the war itself (which was basically an American colonial power-grab) are much remembered or remarked upon by Americans. Enormous monuments notwithstanding, the war had a more lasting cultural impact in Spain, as the country’s embarrassing loss to the upstart United States prompted severe self-doubt among its intellectuals, who were dubbed the Generation of ‘98.

Above us, some of the tallest buildings in Manhattan soared off into the sky. This is Billionaire’s Row, a collection of supertall, pencil-thin, ultra-luxury apartment buildings at the bottom of Central Park. For me, though the skyscrapers are impressive as feats of engineering, the buildings make a dubious addition to Manhattan’s skyline—imposingly tall, but not particularly pretty. And, of course, it is rather depressing to have the city’s silhouette dominated by properties to be used as investments for the super rich.

Almost as soon as we left Columbus Circle, we entered Times Square. Far from a discrete part of the city, Times Square seemed to spread impossibly far, its bright and suffocating tentacles strangling block after block. It seems unnecessary to describe the scene—the smothering crowds of gaping tourists, the blinding lights and flashing signs, the street acrobats occupying the sidewalks, the Elmos and Marios and Mickey Mouses (some with their helmets off, smoking a cigarette)—but I do want to mention the religious fanatic, who was standing on a street corner and yelling that Christianity had abandoned Jesus Christ. A man in a wifebeater stopped to shout “Fake news!” nonsensically at the preacher, and his young son did the same.

Greg and Jay took off like rockets—or, should I say, like real New Yorkers—once we hit Times Square, weaving and bobbing through the crowd like professional boxers. I could hardly keep up, though I did my best. It is a truth universally acknowledged by native New Yorkers that Times Square is to be avoided at all costs. And I have to admit that, by the time we got to the end of it—power walking in sullen silence through the crowds—I yearned for a few porn theaters or gogo bars to scare away the tourists. In other words, Samuel R. Delany may have had a point.

Right as we were approaching the southern end of Times Square, and the limit of our tolerance, we passed by a glowing neon American Flag, in front of which a drag queen was yelling into a megaphone, leading a boisterous anti-Trump rally. Just across the street there was a decidedly smaller pro-Trump rally, trying in vain to maintain a similar energy-level. My favorite character was a very calm black man who stood next to the Trumpers, casually holding a Black Lives Matter sign and chatting to his friend.

From here on, the walk entered its most grueling phase. The sun had set and we were all tired—especially me. In perfect frankness, I was suffering from an affliction that often plagues me during my summers in New York: chafing. Suffice to say that, by the time we got past 42nd street, every step I took was a minor agony. Added to this, I had chosen badly and worn my sandals for the walk, which meant my toes were grinding against pebbles and dirt, covering the sides of my feet in blisters.

By the time we got to 30th street, I was waddling like a duck, and in no mood to appreciate architectural treasures. In any case, the city was quite dark by now—and surprisingly dead. From 42nd street to 14th, we did not pass by a single store that attracted our attention. And though it was a Saturday in midtown Manhattan, the streets were surprisingly empty, mostly consisting of people dressed up for expensive outings elsewhere.

Finally, the Flatiron Building came into view. But something else attracted our attention, a large circular TV monitor. This was the New York-Dublin Portal, an art installation by Benediktas Gylys that opened this year. It is a simple but intriguing concept: a two-way video call so that residents of the two cities can wave at one another. But bad behavior shut down the portal for a week in May. People from both cities couldn’t resist exposing themselves, and a few on the Dublin side had the bright idea to display images of the September 11 attacks.

I was looking forward to waving to some Dubliners (despite the risk of getting flashed). Unfortunately for us, by the time we arrived the portal was closed for the day.

We did at least pause for a drink at an outdoor food stand. It was well past nine o’clock at night and we were all pretty ragged. The prospect of accepting defeat was seriously raised. We did not have much more in the tank. For my part, I badly wanted a shower and to change out of my sticky, stinky clothes. But I wanted to finish the walk even more. And when we saw on our phones that we had just over an hour to go, we decided we had to finish what we started.

Back on our feet—though walking slow—we got to Union Square. In normal times, this is one of my favorite parts of Manhattan (which is generally lacking in green space away from Central Park), but now I just felt a sense of relief that we were recognizably downtown.

I did pause to look up at Metronome, an art installation at the bottom of the park. It consists of a hole that periodically blows smoke rings, next to a series of numbers which don’t make any obvious sense. For years, I would wonder what the numbers might mean, to no avail. It turns out that the digits are a strange kind of clock, displaying (from left to right) the hours, minutes, and seconds from the last midnight, and then the seconds, minutes, and hours to the next one. Not particularly useful, I’d say.

However, since 2020 the display has been repurposed to make a Climate Clock, which counts down years and days to 1.5°C of warming—a number considered to be a threshold for many of the worst effects of climate change. As of this writing, we’re slated to pass over this threshhold on July 21, 2029. Yikes.

Just down the street we passed by one of my favorite spots in the whole city: The Strand Bookstore. It was probably fortunate that, by the time we limped by, it was closed for the day. We couldn’t have survived another delay.

This was the final stretch. The street numbers were falling, 4th, 3rd… until the numbers ceased, and all of the streets had names. We crossed Houston street (pronounced “Howston” in contrast to the city of “Hyooston”) and into SoHo. This was Old Manhattan, Dutch Manhattan, New Amsterdam—the original, chaotic colony, whose criss-crossing streets contrast sharply with the ordered grid of the city’s later expansion northward.

We walked on in relative silence. There was nothing more to say—except complaints. By now I looked as bad as I felt, hobbling down the sidewalk, trying my best to tune out the pain from my lower limbs. I did not have the mental energy to contemplate the African Burial Grounds National Monument, nor to even register City Hall, St. Paul’s Chapel, or Trinity Church…

It was only when we got to the financial district, and passed the iconic Bull Statue, that my spirits lifted. I could smell the water now. We were close.

The final stretch felt like a triumphal march, as we walked through the “Canyon of Heroes.” These are black granite plaques commemorating all of the ticker-tape parades held in New York’s history. You see, it used to be customary to fête important visitors with large parades, in which shredded paper would be thrown everywhere. The tradition started as a spontaneous celebration of the Statue of Liberty’s dedication. Most of the celebrants were visiting dignitaries, heads of state, military heroes, and—most prominently—great aviators. It is a rather charming reminder of the intense excitement of the early days of trans-Atlantic flight.

We finally exited Broadway and entered the Battery. The air was notably cooler, the sounds of the city mixed with crickets. There were surprisingly few people about. We turned a corner and, in the distance, Lady Liberty herself came into view—on the other side of a chain-link fence (a rather depressing image, really). I sat down heavily on a bench, too tired and sore to feel much of anything but relief. But we had made it, from the top to the bottom. It had only taken us 10 hours.

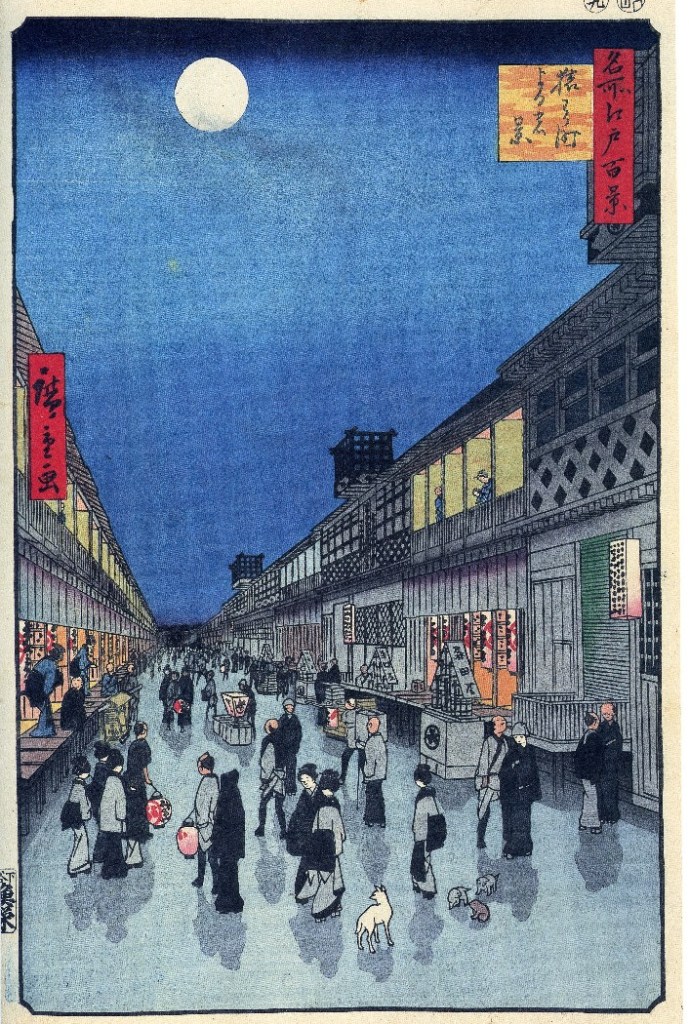

As an epilogue, I wanted to pay my respects to perhaps an unlikely hero of this post: Utagawa Hiroshige. A few weeks previous to this walk, the three of us—Greg, Jay, and I—had seen an exhibit in the Brooklyn Museum of Hiroshige’s celebrated series of woodblock prints, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

What impressed me most in those images was Hiroshige’s ability to display so many different aspects of the city that would become Tokyo: its parks, its seasons, its festivals, its streets and buildings, and its people—from priests to prostitutes. It struck me as remarkable that Hiroshige was able to find such beauty in familiar surroundings. But perhaps all he needed for inspiration was a very long walk.