New Art of Cookery: A Spanish Friar’s Kitchen Notebook by Juan Altamiras by Vicky Hayward

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I did not expect to be going to a book event during my last weekend in Madrid. But when I learned that an author was going to be talking about a historic Spanish cookbook at my favorite bookstore in the city, I decided that I had to make time for it.

I was transfixed from the start. The history of food is, I think, often overlooked—even by history buffs; and yet it provides a fascinating lens through which to learn about the past. In daily life, we are often apt to think of traditional dishes as things that have existed since time immemorial. But this often isn’t the case. In this cookbook, originally published in 1745, you will not find potato omelette, or paella, or croquetas, or cocido, or gazpacho…

Wait, I’m getting ahead of myself. Let me describe what this book is, first. Nuevo arte de la cocina is a cookbook published under the name Juan de Altamiras (a pseudonym) in 1745. It proved to be immensely popular, remaining a bestseller well into the next century. The book’s author—whose real name was Raimundo Gómez—was a Franciscan friar, who grew up and spent much of his life in rural Aragón. This book is a contextualized translation by the English author Vicky Hayward. Throughout the book, she adds a great deal of fascinating historical context, as well as modernized versions of each of the over 200 recipes here.

As you might expect, the book is organized along religious lines, with food for meatless and meat days. Back then, something like a third of the year consisted of meatless days; and during Lent, the pious were supposed to be basically vegan. This makes the book a surprisingly good resource for vegetarian cooking. Yet what made it so innovative in its time was that, unlike so many previous cookbooks, Altamiras wrote for ordinary Spaniards—not courtly chefs. The recipes here are simple home cooking at its finest, requiring basic ingredients and straightforward technique. This was revolutionary at the time.

And to return to my previous point, much of the cooking can seem surprisingly exotic. Altamiras uses sauces made from hazlenuts, almond milk, and pomegranate juice. He mixes citrus, saffron, and tomato, and loves to add cloves and cinnamon to his savory dishes. Hayward was good enough to cook samples for the audience at the book event—several of which made me think of Iranian food. According to Hayward, this is because the Morisco influence (Muslims who had converted to Christianity in the 15th century) was still alive and well in Altamiras’s childhood.

I was also surprised at the wealth of ingredients available to Altamiras. He calls on a wide range of fruits and vegetables, as well as fresh fish—despite not living near the coast. He had eggs aplenty and endless ham and lamb, not to mention nuts, legumes, and spices. Saffron grew locally in his day, and salt cod was a staple (though including such a humble ingredient as salt cod was innovative). Most surprising of all, he made iced lemon slushies by using the snow in the nearby mountains. This was a rich and varied diet.

Hayward has fascinating things to say about all of this—the cooking techniques, the sources for ingredients, the role of religion, the Muslims influence, and so much more. More than so many other history books, this one made me feel transported back in time. And a delicious time it was.

Now, one would think that there could be nothing more innocuous than a translation of an 18th century Spanish cookbook. And yet, the event I went to last month was the first event held in honor of the book—eight years after its initial publication! According to Hayward, this is because her book attracted the ire of the Aragonese government, who were offended that a foreigner had beaten them to the punch in bringing their native son to a wider audience. She reports being attacked left and right by Spanish academics. If this is true, it is very silly.

I left the event in a buoyant mood, glad that I could still be so surprised by Spanish history after so many years. And I celebrated, appropriately, by the orgy of food that is Tapapiés—Madrid’s annual tapa festival, held in the Lavapiés neighborhood. It was a wonderful way to spend my last Friday in the city.

View all my reviews

Author: Roy Lotz

Difficult Day Trips: Patones de Arriba & Las Cárcavas

For years I had been beguiled by images of Las Cárcavas—a crazy undulation of land, tucked away in the sierra of Madrid. Photos made the place seem otherworldly; and I was dying to see it for myself. Unfortunately, however, there did not seem to be any good way to get there on public transport. Studying the bus routes and the map, I found that the closest that I could get was a tiny village that I’d visited once before: Patones de Arriba.

So early one Saturday morning, I took the metro to Plaza de Castilla, and caught the 197 bus to a small village called Torrelaguna. From there, I caught the 913 bus—a mini-bus, which followed the winding path up a hill to the old and picturesque village of Patones de Arriba. I was the only passenger on board that day. And by the time I arrived, it was still so early that the streets were virtually empty.

Patones de Arriba (unlike its modern cousin, Patones de Abajo down the hill) is a time capsule of a place. It seems to have survived virtually unchanged since antiquity. Stone huts cover an otherwise barren hillside—the town hidden among the foothills of the sierra, in a place that would be naturally defensible should any dare to attack it.

The architecture is a prime example of what the Spanish call arquitectura negra: all of the buildings made out of the distinctive black slate of the area, which naturally breaks off into thin plates. This gives the town a striking uniformity—both between its buildings, and with the landscape. The tallest building is the old church, though nowadays it is used for the tourism office. Indeed, I am not sure that anyone actually lives in Patones de Arriba these days—it is a kind of living museum attached to the modern settlement below.

The town is full of relics of its agricultural past. There are stone threshing floors (for separating the wheat from the chaff), pig pens, and cattle sheds. We can also see signs of village life, in the form of ovens, wine cellars, and laundry basins, all made from the local slate. But the real pleasure of visiting the village is simply enjoying the ambience of the past—and, perhaps, a good lunch. On my first visit, years prior, we went into one of the restaurants and had a hearty meal of good Spanish mountain fare—bean stews and red meat.

But by the time I arrived, there was nothing open and, apparently, nobody there. So I walked through the town and then out into the surrounding hills, on my way to Las Cárcavas.

The countryside here is, like much of the interior of Spain, windswept and bare. In the best of times, the soil and rain could not support luxuriant vegetation; and, in any case, centuries of human habitation have destroyed a large portion of the old forests. The result is that much of Spain, though dramatic in its vistas—the view extending until the horizon—unwinds itself in a patchy surface of rocky ground covered with low shrubs.

The walk was long, winding, and somewhat monotonous—going up and down hill after hill. The only thing to attract the eye were the many pieces of water infrastructure. Large tubes shot out of the hillside, down into valleys and back up again. Further on, stone aqueducts crossed from elevation to elevation. Finally, the explanation for all this came into view: the Pontón de Oliva.

This mammoth construction was the first dam built under the auspices of the Canal de Isabel II, the organization responsible for Madrid’s water supply. And this brings me to a small detour in our hike. Like New York City, you see, Madrid has long struggled to supply its citizenry with clean, safe drinking water. And this is due to the location of both cities: New York is surrounded by brackish, dirty, ocean water, while Madrid has virtually no natural water sources to speak of.

When Madrid was still a relatively small city, local wells and streams were enough to solve this problem. But by 1850, with the city’s population nearing a quarter of a million, the lack of water was becoming a serious issue. The engineers in both NYC and Madrid hit upon the identical solution: dam the rivers in the mountains to the north, and transport the fresh mountain waters to the thirsty city. The Pontón de Oliva was the first step taken in this effort.

It was constructed during the reign of Isabel II, who became the first (and, so far, the only) ruling queen of modern Spain after a succession dispute, which involved a rebellion by her uncle, don Carlos. These wars, called the “Carlist wars,” ended in her victory. This left the new queen with quite a few prisoners of war, whom she put to use building this dam under extremely gruelling conditions. (I tried to look up the number of prisoners who died during the construction, but I couldn’t find it.) To make matters worse, the engineers who designed the dam had chosen a bad location of the river Lozoya, making it all but useless. Today, it stands as a kind of monument of wasted effort—something for hikers and history buffs to appreciate, but dry as a bone.

Just beyond this dam, I finally arrived at my goal: Las Cárcavas. Now, “cárcava” is just the Spanish word for “gully” (though it certainly sounds more attractive); and this one is just a particularly big example of a common phenomenon—namely, water erosion. Though the details are complex, the principle is quite simple: intermittent water flow down steep terrain causes rivulets to form, creating a distinctive undulating pattern as they wear their way through the landscape.

I stood on the lip of this gully and sat down, absolutely exhausted. I had been walking for several hours by then, up and down hills, with no shade from the punishing June sun. Now it was past noon, and the temperature was climbing. I ate my packed lunch (a tuna empanada and a small bottle of gazpacho) as I observed a column of ants make their way through the dusty earth, and amused myself by tossing them little bits of fish. Then, after getting my fill of this alien world, I drained my water bottle and got wearily to my feet.

Water, I have discovered, is a powerful thing. It can move landscapes and determine the destiny of cities. And I found now that I hadn’t brought enough of it. I had well over an hour before I could make my way to civilization, all of it under the merciless Spanish sun. And I was already thirsty. The only choice was to press on. Attempting to distract myself with an audiobook, I walked down the hill, past the dam, and onto a local road.

At just the point when I was risking heat stroke, I arrived in Patones de Abajo and stumbled into the nearest bar. There, I ordered the biggest “clara” they had (beer mixed with lemon soda), and then ordered another one. Then, after another long bus ride back to Madrid, I enjoyed glass after glass of the city’s fine tap water—water that had itself been on a journey from the sierra—which, I found, tasted especially good that day.

From Madrid to the Skies: the Planetarium and the Royal Observatory

“¡De Madrid al cielo!” is something people here like to say—meaning, I suppose, that Madrid is so marvelous that it can only be surpassed by a visit to heaven itself. And Madrid certainly is marvelous, not least for its big open skies, so often completely cloudless. Indeed, there are two institutions in the city dedicated to exploring the air and space above: the Planetarium and the Royal Observatory.

The Planetario de Madrid is a futuristic-looking building located in the south of the city, in the Tierno Galván park. Climbers scale the large concrete wall nearby, and electronic music festivals are often held in the park’s center. Constructed in 1986, the Planetarium gives the impression that it is how the designers imagined houses might look on Mars, in the distant year 2025.

Underneath the bulbous dome of the planetarium is a semi-circular screen, where educational programs are projected—cartoons for kids, documentaries for adults, and educational sessions for school groups. Through an oversight, I once sat through a film about velociraptors who constructed a space ship and traveled throughout the universe, only to return to earth and find the bones of their ancestors in museums.

Apart from these films, the Planetarium has a small exhibition space, where the visitor can see short educational films on the solar system, gravity, and the history of the universe. There are replicas of Mars rovers and space suits, as well as displays on the Milky Way and the moons of Jupiter. Most beautiful, I think, are the photos of distant galaxies and nebulae, taken by the Hubble Telescope and gently illuminated. The universe is a frighteningly beautiful place. All this being said, I think the exhibit space is rather light, and in general the Planetarium is geared towards younger audiences. Still, it is always worthwhile to contemplate the stars.

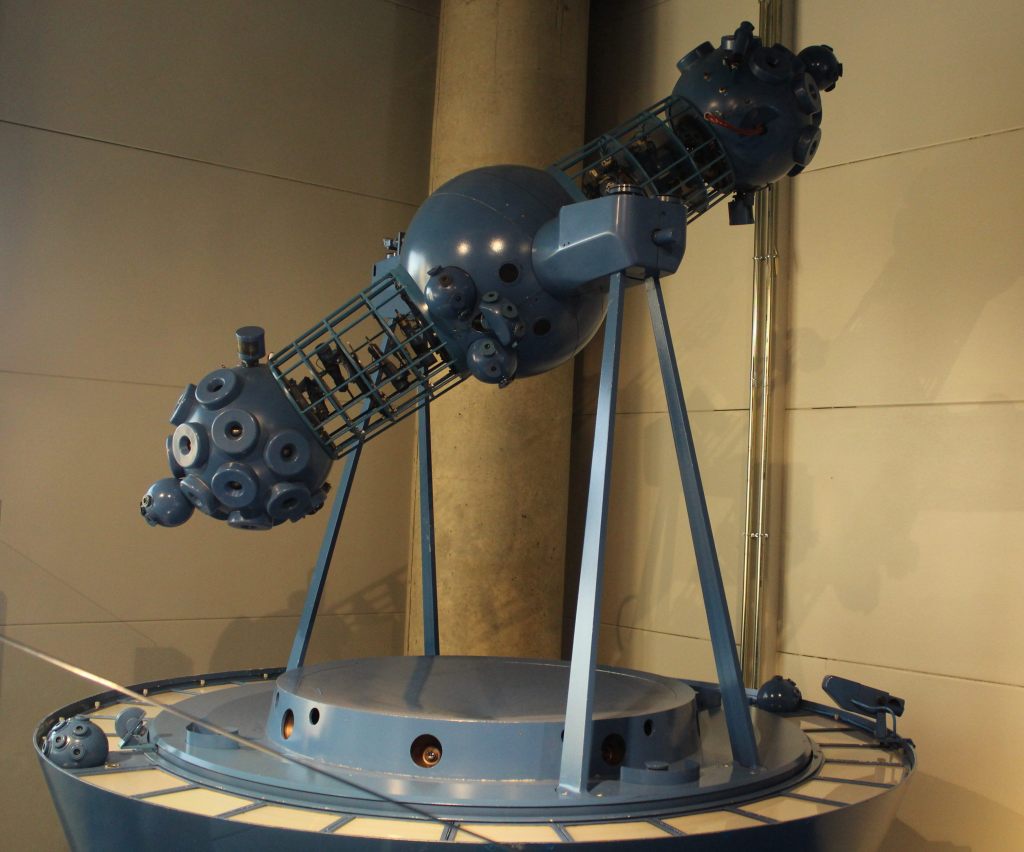

The Real Observatorio is certainly not a visit for kids. This royal institution was founded in 1790 by Carlos III, and it bears all the hallmarks of its Enlightenment origins. The Observatory is a kind of temple of science—housed, as it is, in a cathedral-like building designed by the great architect Juan de Villanueva. To visit, you need to reserve a spot on a guided tour, which are only available on weekends (and I believe are only available in Spanish). But if you have any interest in the history of science, the visit is certainly worth the trouble.

The tour begins in the great edifice of Villanueva, which preserves so much confident optimism of the Age of Reason. In the great hall, a Foucault pendulum hangs from the ceiling, making its slow gyrations. This device—the original of which hangs in the Panthéon of Paris—is a demonstration of the rotation of the earth, as the planet’s movement under the pendulum makes it appear to spontaneously change direction.

Distributed around the space were any number of beautiful antique telescopes and other scientific devices—crafted by hand out of polished brass and carved wood. Antique clocks hung on the walls in abundance, as if the scientists of that era had to double- and triple-check the time for their observations. In the main chamber, a large telescope occupied the center of the space. There, mounted like a canon, a metal rod is pointed at the slotted ceiling. Below it, a plush chair with a folding back allowed the scientist to look through it from either side.

But the star attraction of the Observatory is held in a different building, a short walk from the Villanueva edifice. This is the great telescope of William Herschel, the English-German astronomer. This huge contraption was built in an English shipyard in 1802 for the new Royal Observatory. It was to be the center of the whole scientific enterprise. Unfortunately, fate soon intervened in the form of Napoleon, whose troops occupied the Royal Observatory (it has a strategic vantage point on a hill) just a few years later. These soldiers melted down the metal parts of the telescope for munitions and used the wood to keep warm. Thus, the current telescope is a careful reproduction, completed in 2004.

The tour ends in the Hall of Earth and Space sciences, a kind of miniature museum that is run by Spain’s Instituto Geográfico Nacional. The exhibit is divided into four sections: astronomy, geodesy, cartography, and geophysics. Each display is full of yet more scientific instruments, both old and new. There are armillary spheres (for determining the position of the planets in the sky), theodolites (for surveying land), and samples of volcanic eruptions from the Canary Islands. My favorite was a lithographic plate used in the printing of the National Topographic Map—the official, hyper-detailed, super-accurate map of the country.

The Royal Observatory is still an active scientific enterprise, monitoring both the skies above and the earth below—though the amount of light pollution in the city makes even Herschel’s great telescope largely useless. Instead, they receive data from far away telescopes, such as the Gran Telescopio Canarias, located high up in the mountains of La Palma, above the clouds and far from major city centers.

Yet even if Madrid’s skies no longer serve the purposes of science, they still inspire locals and visitors alike. As I write this, I am peering up at the blazing ethereal blue of a mid-September day, with the laser-like sun casting sharp shadows on the street below. It is, indeed, just one step short of heaven.

Collision 2025: The Joy of Losing

I got off the bus into a bright August day, climbed the stairs to the Meadowlands Exposition Center, and then gave my ID to a young man at the door. He handed me a lanyard that read: “COMPETITOR.” For the first time since high school, I was going to compete in a video game tournament. And it was a big one: Collision 2025.

The space was huge, gray, and bare. On both sides of the cavernous room, rows and rows of monitors and consoles were set up, ready to be played. In the back was the main stage, where the final matches would be projected onto a big screen. By the time I arrived, early on the first day, relatively few people were about. The main events wouldn’t begin until the following day.

I walked around and tried to get my bearings. Nothing much was happening. A few dozen people were playing so-called “friendly” matches (not competitively), while others were simply milling about. Yet there was a quiet intensity to the space. Though the event was dedicated to video games in which cartoon characters beat each other up, it was clear that the attendees were not here to have fun. They were here to play, and to win.

Suddenly, a strange panic began to take hold. It was a feeling that I hadn’t had since I was a teenager: the paralyzing fear of being badly beaten at a video game. From the first moment, I could tell that I was simply not at the same level as even the average players here; and I felt sure that, if they saw me play, I would be laughed at. I felt ridiculous: a man at the age of 34, having lived in a foreign country, published several books, and worked for years as a teacher—paralyzed with fear at the thought of losing a video game. But the anxiety was real.

Indeed, it was so real that I had to leave the venue. Breathing heavily, I sat at a bus stop and even contemplated leaving, despite having paid a significant amount to sign up. But that would be cowardly, I decided. So I walked to a nearby diner, sat down, and ate an omelette. Then, still rattled, I walked to the Mill Creek Marsh Trail, a park that consists of a path through restored wetland. There, I took a deep breath, put on my headphones, and focused: “It’s just a freaking video game,” I told myself: “I can do this.”

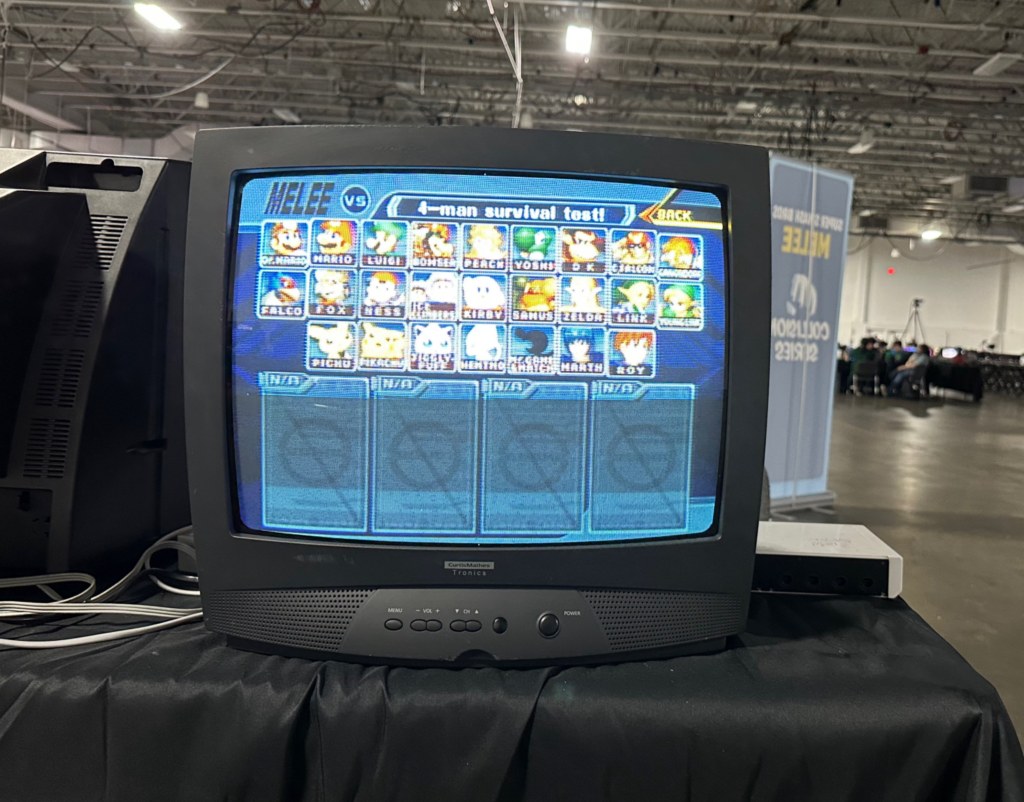

I should give you some background. Super Smash Bro. Melee, released in 2001 for the GameCube, is the second iteration of one of Nintendo’s most popular games. Despite its age, the game is still played avidly: its fast and complex mechanics make it the most competitive version of the franchise.

As I’ve written about elsewhere, this game was a big part of my teenage years. I played it with friends and neighbors, and even brought it to school to play during breaks. And after one of my college suite mates brought his old GameCube to our dorm, I once again went through a heavy phase of Melee. But I hadn’t touched a controller since 2013, when I graduated college.

Despite this, I maintained an active interest in the game. Though I’ve never been a sports fan, I somehow became a fan of competitive Melee. Every so often, I would lose myself down a YouTube black hole, watching game after game after game. And this, despite fancying myself too enlightened and cultured for video games. For a long time, it was a secret vice. And despite my shame, I dreamed of someday playing it again.

Then, during my Christmas break, 2024, something fateful happened: my brother discovered our old GameCube in the basement of my mom’s house. Inside was Super Smash Bro. Melee. It even had our old memory card. For the first time in over a decade, I could play my favorite game. It was heaven: surrounded by all of my old friends, playing the exact game we used to play, rediscovering the pure joy of being kids. I enjoyed it so much, in fact, that I decided to take the GameCube with me back to Spain.

Eight months of practice later—most of it on my own, against the computer—I decided that it was time that I take my first real step into the world of Melee. My brother sent me the link to Collision 2025, a large tournament set to take place in New Jersey (indeed, so many important players would attend that it was classed a “supermajor”), and I decided that I had to sign up, even though I had no chance of even making it past the first round.

So here I was. I was still so nervous that I decided that I couldn’t allow myself to hesitate again. Thus, I walked back into the expo center, plugged in my controller into a free console, and started to warm up against a computer. After just a minute, however, somebody sat down next to me. “Wanna play?” he asked.

Thus began my own friendlies. As I expected, I was far worse than virtually everyone in attendance, and our matches mainly consisted of me being tossed around like a rag doll. Still, it was a fascinating experience—to finally see for myself how I measured against serious players. It was like playing against a professional tennis player after practicing in the park with friends: we were hardly playing the same game.

Yet much to my relief, everyone I spoke to was welcoming and kind, even as they whooped me. And I learned much about the game which I would never have learned by simply following it online.

For example, I discovered that controllers are an entire world unto themselves. Throughout the venue, there were several stands selling tricked-out controllers—for hundreds of dollars—or offering customization services, swapping out buttons and joysticks. And here I was, with an original, unmodified GameCube controller from 2001.

One player I played, JKJ (everyone goes by a “gamer tag” at these events; mine is Royboy), gave me a close-up look at his controller: it had fabric wrapped around the handles, and extra notches around the joystick. These notches are a controversial topic, as it makes it easier for players to angle their joysticks more precisely. JKJ explained that he thought notching was unsportsmanlike, but he started doing it because the practice is so widespread.

Another player I met—whose gamer tag I can’t recall, but whose real name was John—played with a different kind of controller entirely. It was a kind of black rectangle, the size of a traditional keyboard, but with much larger buttons. This is the B0XX Controller, which was developed by the smasher Hax$ (who died under tragic circumstances) for those suffering from joint and wrist problems.

“Are you squeamish?” he asked, after I inquired about the controller. I said “No,” and he showed me a video taken by his surgeon: his wrist was sliced open, and a gloved hand was manipulating his arm to show the tendons, muscles, and nerves. John explained that he was practicing on a traditional controller (“frame-perfect ledgedashes,” if you want to know the technique) when he felt something pop in his wrist. Apparently, a tendon had snapped out of its sheath, causing severe pain.

Now, after surgery, he has a scar and uses this ergonomic controller. Just because it is a video game doesn’t mean that you won’t get an injury.

I spent several hours playing and socializing before deciding to call it a day. The next day, Saturday, was when the real tournament began. At least I was warmed up.

For me, Melee is pure nostalgia. But the next day brought even more nostalgia, in the form of Jackie Li. Jackie grew up with me and my brother. He was over at our house so often that he might as well have been a third sibling. We would spend hours each day together. My mom would give him rides to school in the morning. He knew everyone in my family—even coming up to see my grandparents in the Catskills.

Like many kids, our main activity together was video games. We played them obsessively as kids. And Jackie was always the best. Nowhere was this more true than with Melee. Although I took the game very seriously, spending hours honing my technical skills, and although I could beat everyone else, often quite easily, I could never beat Jackie. He would win nine out of ten games, and no amount of practice ever seemed to bridge that gap.

My failure to beat him even followed me to college, as we both attended Stony Brook University. My suite mate got a GameCube, and I commenced to beat everyone who sat down to play me. But when Jackie came over, I still couldn’t win.

But all of us drifted apart after college. Partly it’s because I stopped playing video games, and partly it was simple neglect, and partly it was my move to Spain. But the impending tournament jogged my memory, and I decided that I had to reach out to Jackie. More than a decade had gone by, and I didn’t even have his phone number. So I sent him a message through LinkedIn. He agreed, and on Saturday morning he met me and my brother in Port Authority, looking just as he looked the last time I’d seen him.

Seeing somebody from your past after so long is almost trippy. It is a disorienting mixture of familiarity and strangeness. You know one another intimately, and yet hardly know one another at all. But it did make one thing clear to me: Our memories are stored in other people.

As I spoke to Jackie, huge swaths of my childhood came flooding back—nothing terribly important, but lots of little things, things that I hadn’t thought about in a long time.

So much of what we think of as “maturing” involves forgetting—leaving behind old identities that no longer serve us. There is definitely a power in this, the power of reinvention. But there is also a kind of spiritual danger, I think, since we can forget important aspects of ourselves.

Becoming an adult, I’ve found, eventually means integrating some of the identities we left behind, at least to some degree. And though it’s silly, I think my own changing attitude towards video games illustrates this process. When I was younger, video games were pure fun—absolutely engrossing, an escape from life, a competitive thrill. But at a certain point I forswore them: I decided that they were for losers, a huge waste of time, and brought out the ugly competitive side of players.

This was useful to me, since it allowed me to focus on socializing, on music, on school, and so on. But this left a huge part of my childhood as a black hole, a write-off. Now that I’m older, I’ve come to see video games as a qualified good. They are, after all, just a type of game; and our love of playing and creating games is one of our species’s most distinguishing qualities. Of course, their nature makes them more addictive than, say, Parcheesi. But nobody who has witnessed football culture in Europe, or even the steel-willed dedication of an avid chess player, can argue that video games are uniquely bad in this respect.

Indeed, crazy as it sounds, I am now inclined to say that Super Smash Bros. Melee must be one of the greatest games ever made. And now I was ready to compete.

The three of us entered the venue and sat down to play. Jackie was going to help me warm up before the tournament. This was like being in a dream. Here I was, over a decade later, ready to play my arch-rival—the one who I learned with, the one who always beat me. All these years later, what would the result be?

Strangely, anticlimatically, the result was nearly the same as it had always been: He still had a serious edge on me, beating me in about 90% of our matches. (It turns out that he was also practicing occasionally over the years.) And this brings me to another fascinating aspect of this game, and of games in general: the reality of skill.

Now, if you don’t know much about Melee, the game could seem to involve a great deal of luck. After all, players are making split-second decisions in situations that, chances are, they had never seen before—at least not in that precise configuration. The same is true of many games and sports: to the untrained eye, they seem to be up to chance as much as skill. But the reality is that skill is something as real and tangible as a controller: it is measurable and tends to be fairly consistent through time.

The results of the tournament speak for themselves: the first, second, and third place finishers (Zain, Hungrybox, and Joshman, respectively) were the first, second, and third place seeds. In other words, the results were exactly what was anticipated based on the player’s rankings.

This is not to say that there weren’t “upsets.” The 4th-place finished, lloD (a practicing doctor, as it happens), was seeded 13th; and the 7th-place finisher, Zamu, was seeded 23rd. Clearly, a player’s official rank isn’t a perfect reflection of their skill at a given moment (and we should be grateful for that, as the game would be boring to watch otherwise). But what strikes me as more notable is that even these “upsets” weren’t radical miscalculations. It is not as if a player came out of nowhere to finish in the top 8.

Another striking feature of skill is how it can appear to follow an exponential scale. I will illustrate this point with my own tournament experience. My first-round opponent was a player who went by “notsmoke.” He beat me handily, winning every game by a significant margin. The set was over in less than 10 minutes. But as soon as I congratulated my opponent, his second-round pick sat down for the match. This was Agent, a ranked player, who proceeded to beat notsmoke nearly as badly as I’d just been beaten. Agent was, in turn, knocked out handily by Zuppy, who in turn was eliminated without much ado by Moky. And on and on.

The striking thing about all this is that, to me, the skill levels of (say) Agent, Zuppy, and Moky appear to be nearly indistinguishable, and yet there are significant chasms between each of them. And the gap between Moky and Zain (the winner of the tournament) is just as significant still.

To round out my own tournament experience, I had one more match to play before I was knocked out entirely. My new opponent was ENFP, who beat me even more dramatically than notsmoke (though rather politely, I should add). And that was it for my stint as a competitive gamer.

The rest of our time at the Meadowlands Exposition Center was just spent watching. And here I want to add a note on the demographics. As you might imagine, the large majority of the attendees were male (stereotypes do sometimes hold true). But I was surprised, and charmed, by the significant number of trans people. When I was a kid, video game culture was quite misogynistic and homophobic (and perhaps corners of it still are); but now, players are introduced along with their pronouns. Most everyone was in their 20s and 30s, though some were considerably younger. For example, one up-and-coming player, OG Kid, is (as his name suggests) still a teenager—meaning that he is younger than the game itself.

One jarring aspect of the tournament was seeing so many famous players. Virtually all of the major competitors were in attendance, with the notable absence of Wizzrobe (who dropped out last minute), Cody Schwab (the current #1 player), and Mang0 (often considered the greatest player of all time, who had just been banned due to his drunken misbehavior at another event). Everywhere I looked, there were faces I recognized: Axe, Salt, Junebug, Aura, Nicki, Aklo, Jmook, Trif… I was starstruck, but then realized that none of these people is, in truth, really famous. They were legends only in the context of a fighting game that is over two decades old.

Floating among the crowd, his hair died blond, was Zain—the current #2 player and the heavy favorite to win. He was surrounded by people who knew exactly who he was, who admired and envied him; and yet he seemed to be separate from the crowd, just drifting from place to place. At one point, he stood next to me as I observed a match—the tournament’s eventual winner next to its last-place finisher. And it occurred to me that I had never stood so close to somebody so good at anything.

Zain stood there—alone in a mass of people dedicated to this game, people who had collectively devoted hundreds of thousands of hours to honing their own skills—secure in the knowledge that he could beat any one of them. And it made me reflect on why people devote themselves to such seemingly pointless activities.

Aside from fun (and the game is very fun), the most obvious answer is escapism: to focus your attention on something unrelated to your daily life, where there are no consequences. But that is not the whole story. For some, it is the community—being a part of like-minded people, the chance to make friends and share interests. And the game also offers an opportunity to forge a new identity— nerdiness transmogrified into coolness.

But for Zain, and those like him, I realized that they were here for something else: the pure pursuit of a skill—skill for the sake of itself, being the best they could be at this one specific task. There is something almost inhuman about it—requiring, as it does, such single-mindedness of purpose that everything else in life becomes secondary. And yet, in a way, this pursuit of skill for its own sake might be the most human quality of all—the quality that drives us to the highest reaches of excellence.

But there is a high price to pay. The irony is that, thanks to my reunion with Jackie, I probably enjoyed the tournament quite a bit more than its champion. And to enjoy things you’re bad at—to enjoy them, especially, with old friends—is also a very human quality.

Two Royal Factories: Tapestries and Glass

A crucial moment in the history of Spain was the transition from the Habsburgs to the Bourbons, a result of the War of Spanish Succession. With the French Bourbons came French ideas and sensibilities, among them the mercantilism of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, based on limiting imports and maximizing exports. To foment national manufacturing, the crown created various “royal factories” throughout the country, many of them focused on luxury goods—literally fit for a king.

Not all of these factories survive. The Royal Factory of Porcelain, for example, was destroyed by Wellington’s troops during the Napoleonic invasion of Spain. Nowadays, the curious visitor of Retiro Park may notice only a few scattered ruins of the enormous building. Others have changed function. The Royal Tobacco Factory in Embajadores, for instance, has become a cultural center, known as the Tabacalera (currently closed for repairs).

Yet a handful have retained their original purpose. Among these is the Royal Factory of Tapestries. It is housed in a lovely brick neomudéjar building near Atocha. Visiting is not especially easy. The factory is only open during the week, and only during the morning. To visit, you must write them an email with your ID number and join one of the four daily guided tours. If you are unlucky enough to work during the week, a visit is close to impossible. I went on a hot July day, after school had ended for the summer.

No photos are allowed during the tour, and for obvious reasons. It is still a working factory, full of women (there were only a couple men) weaving industriously. I wouldn’t want to be photographed by legions of strangers either. But this gives the visit a rare intimacy. The weavers sit at enormous, antique looms, their hands in constant motion. Using a pattern, they put together their tapestry stitch by stitch, knotting the thread with a single hand, so quickly and dextrously that it is impossible to follow their motions. It is both beautiful and, I imagine, incredibly dull, as they patiently put the tapestry together millimeter by millimeter, day after day, week after week.

The curious reader may be wondering who on earth is ordering and paying for these tapestries. They wouldn’t fit in most homes and, besides, are a bit old-fashioned as decoration. The commissions come from museums and other historical institutions. The tapestries I saw, for example, were for a German palace being renovated for visits.

Further on the tour, we were introduced to a resident artist, who was designing an enormous new carpet for the Almudena Cathedral here in Madrid. He held up the design and explained why he had chosen the shapes and the colors—the apparently abstract pattern had a well thought-out logic. Then we were led to the refurbishing wing, where old tapestries and carpets are given new life. The work that goes on here is, I imagine, even more painstaking than the new commissions. If memory serves, the factory is even equipped with a kind of enormous pool used to gently wash antique fabrics.

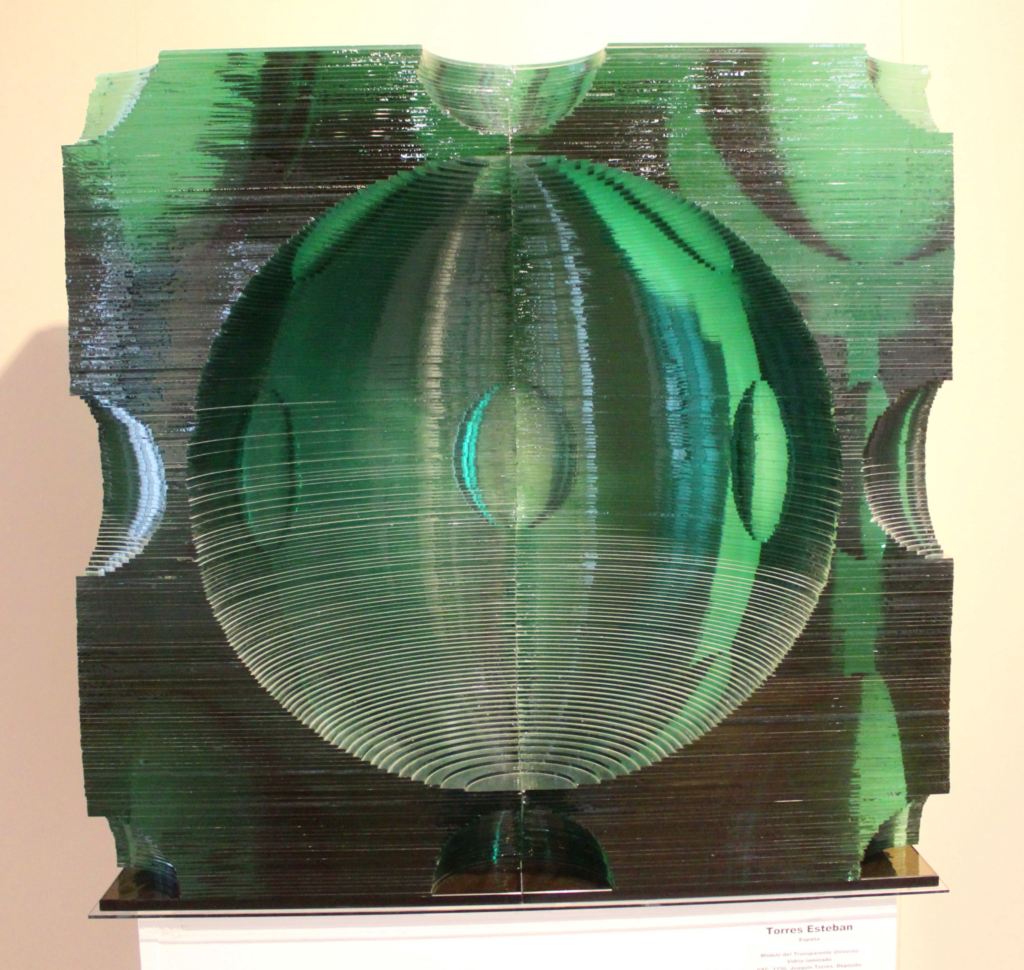

The other royal factory I have visited is located somewhat outside Madrid, in the province of Segovia, in the town of La Granja de San Ildefonso. This town is more famous for being the site of an enormous royal palace—one of the finest in Spain, complete with gardens that emulate (if not exactly rival) those of Versailles. Yet for my money an even more interesting place to visit is the Real Fábrica de Cristales.

As you might expect, this factory originated to supply windows and mirrors for the royal palace that was being constructed nearby. But it went on to produce high-quality products for more than a century after the palace’s completion. Nowadays, unlike the tapestry factory, it is mainly a museum space, dedicated to both the history and contemporary practice of glass blowing. And it is a fascinating place.

First, the visitor can see an expert glass blower giving demonstrations in the working furnace. As there are usually not many visitors, this can be an intimate experience, separated by just twenty feet from the artist. The temperatures involved are intense, in the range of 1000 degrees Celsius, and it is difficult to see the melting, molten glass without imagining how horrendously dangerous it must be to work with the stuff. It is thus all the more impressive to witness somebody turn this lava into delicate, lovely shapes.

The main factory space is full of old industrial equipment—for making windows, mirrors, bottles, and other products. This is all housed in a large, cavernous, almost cathedral-like nave, whose high ceiling and brick exterior testify to the great risk of fire. Indeed, the factory was intentionally built at a remove from the palace, beyond the original walls of the town, for this very reason. In another room, there is a small exhibit on the art of stained glass; and several stunning examples of the factory’s chandeliers hang from the ceilings.

My favorite part of the visit was the section devoted to contemporary art. Here you can see glass shaped, layered, and twisted in ways that hardly seem possible. Particularly beautiful was the work of Joaquin Torres Esteban, whose sculptures as so startling—by turns abstract, mathematical, and precise—that you wonder whether glass is being underutilized as an artistic medium.

In sum, the Real Fábrica de Cristal is my favorite sort of museum: lesser-known, provincial, and yet full of surprises. It is certainly unlike any museum I’ve ever visited. In any case, the royal factories are a fascinating subject for those who, like me, want to go beyond the major monuments. And I’m sure there is a lot more worth exploring.

Review: Stray Cats

Stray Cats: Life in Madrid Through 17 Voices by John Dapolito

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I met John Dapolito at the Antón Martín metro stop on a cold autumn night. He was smoking a cigarette and scanning the crowd, and when he recognized me he told me to follow him to a nearby bar. I was nervous, as this was a kind of interview. He was looking for writers to contribute to a new volume, a collection of mini-memoirs of people who have moved to Madrid from elsewhere. He wanted them to answer three questions: How has Madrid changed since you moved here? How have you changed? And how has Madrid changed you?

“Nine years?” he said, mulling over my time in Madrid. “Nine years…” his voice trailing off. To many Americans in Madrid, this is quite a long time. But compared to John’s twenty-five, it seemed rather paltry. So we talked about how I could write my essay, what angle I could take, what I could emphasize about my experience to differentiate from everyone else’s. The next day, I started writing a draft of my essay long-hand, in a notebook—something I seldom do—and now it is a pleasure to see it in print in this collection.

Ironically, in the months since I sent off the final draft to John, I’ve grown to love Madrid more than ever. While I used to feel the need to escape into the sierra every couple of weeks, craving a bit of nature, lately I’ve been content to just stroll around the city, exploring its nooks and crannies, and getting ever-more integrated into its peculiar form of life. In short, now that my nine years are nearing ten, I am finally beginning to feel like a proper madrileño, fully at home in this great Spanish metropolis. And now that I have my story of Madrid in print, I feel now more than ever that I’ve really made a home here.

The stories in this volume have many common themes: learning the language, enjoying the nightlife, resenting the gentrification, and so on—themes that would have appeared had this book been written about Budapest or Bangkok. But beneath these superficial commonalities are what make the essays worth reading—insights into Madrid and, more often, into the person writing about it. And these essays are illustrated by black-and-white photos by the editor, John. I remember him opening a binder of them at the bar, during our first meeting, and admiring their atmosphere, how they really captured an aspect of the beauty of this city. And I thought to myself: “I want to be a part of this project.”

View all my reviews

Modern Art in Old Castille

When I first came to Europe I was, like any good American, in search of the very old. We have skyscrapers and Jackson Pollocks in my country, but we don’t have cathedrals, castles, or El Greco. Yet to see Europe as merely a repository of its history is to forget that its residents are just as keen as anyone to advance into the future. And so I recommend any visiting Americans to make time to experience a bit of the more modern side of Spain.

Segovia, for example, is justly famous for its Roman aqueduct and its elegant cathedral. But tucked away in its winding streets is the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Esteban Vicente. This small museum would be worth your time even if it weren’t free to visit. It is named after an important but lesser-known artist from the 20th century, a member of the famous Generation of 1927 (which also included Lorca and Dalí), who spent time in Paris alongside Picasso, and finally moved to New York City in the wake of the Spanish Civil War. There, he became one of the main representatives of abstract expressionism.

The museum is housed in what used to be a hospital; and the large rooms and austere architecture contrast starkly with the art. Though he began as a figurative painter, Vicente quickly moved into the kind of abstract art that many people turn up their noses at—atmospheric blobs and swirls of color on canvas. I must admit that it isn’t usually my cup of tea, either. Nevertheless, in the context of Segovia, a city of narrow streets, hard angles, and gray stone, his art was wonderfully refreshing—light and playful, almost ethereal in its vagueness.

When I visited, there was a temporary exhibit by the contemporary artist Hugo Fontela—another Spaniard working in the abstract vein, living in New York. He worked in a very restrained color pallet, just green on a white canvas. Yet with the rhythm and intensity of his brush strokes, he managed to evoke clouds, waves, wind, and whole landscapes. It was an impressive performance.

Even deeper into Old Castile is the city of Valladolid. Though often overlooked by tourists, it is a city well worth visiting, especially as it is easily accessible by fast train from Madrid. Among the curiosities of the city is its huge and rather ugly cathedral—a massive pile of stone that looks oddly unfinished. This is because, when it was conceived, Valladolid was serving as the capital of Spain, and so its church was meant to be the biggest in the world. When the capital was moved to Madrid, however, the construction stopped, and now the building trails off into nothingness.

The most famous museum in the city is the Museo Nacional de Escultura, a collection of sculptures from the middle ages onward (mostly religious), housed in an old monastery. However, during my brief time in Valladolid, I found my visit to another museum far more enjoyable: the Museo Patio Herreriano.

The museum is located in the remains of the former monastery of San Benito el Real. Though its name pays homage to the great Spanish architect Juan de Herrera, it was really designed by one of his followers, Juan de Ribero Rada. However, the building was in such disrepair by the time it was decided to create a museum that substantial renovations were necessary. The building now is thus a strange Frankenstein mixture of old and new sections.

The museum’s collection is huge and extensive, containing works by Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, and even our friend Esteban Vicente, as well as contemporary artists such as Azucena Vieites. I wandered around rather aimlessly, having neglected even to pick up a map, doing my best despite being sleep-deprived and dehydrated to appreciate the art. I would be insincere if I pretended that I liked everything. Indeed, contemporary art often leaves me scratching my head and even vaguely bored.

But any kind of art is largely hit and miss; and contemporary art even more so. Going to a modern art museum, therefore, requires a certain suspension of judgment, a certain amount of patience, until you discover something that pulls you in.

For me, this was an exhibit on Delhy Tejero, a Spanish artist I had never heard of before. What immediately struck me about her work was how varied it was, in both style and content. She could do realistic, figurative drawings or highly abstract paintings; her work can be cartoonish, dreamy, or serious; she can focus on folklore or lose herself in the purity of geometric shapes. Perhaps none of the works on display was a surpassing masterpiece, but taken as a whole her work exemplified such a degree of curiosity, open-mindedness, and fine sensibility that it left me deeply impressed.

These are just two examples of the fine, lesser-known modern art museums to be found all over Spain. And I think that, especially for the weary traveller, traversing the scorched soil of the central Castilian plains, besieged by castles, cathedrals, and ruins of bygone civilizations, a bit of absurdity, playfulness, and abstraction can do much to clear the palette.

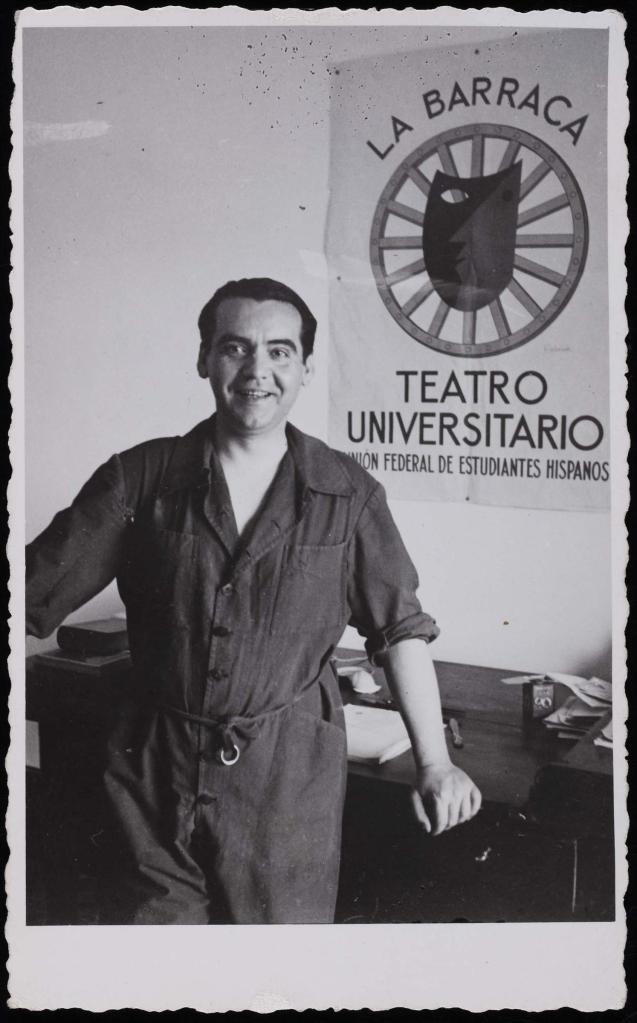

In the Footsteps of García Lorca

Federico García Lorca is the most famous playwright and poet that Spain produced in the previous century. This is largely owing to undeniable brilliance, as any readers of Bodas de Sangre or Yerma can attest to. Yet his fame is also due, in part, to the tragic story of his death—executed by Nationalist forces during the first few months of the Spanish Civil War. Among the hundreds of thousands dead from that conflict, Lorca remains its most famous victim. And in death, he has become a kind of secular saint to artistic freedom.

The precise details of Lorca’s murder were, for a long while, rather obscure; and it is largely thanks to the Irish writer, Ian Gibson, that it was finally uncovered. Prior to our trip to Granada, Rebe had read Gibson’s book, El asesinato de García Lorca, and so we had a full Lorca itinerary planned.

Our first stop was the Huerta de San Vicente. This was the summer house of the García Lorca family for the last ten years of the poet’s life. It is a kind of rustic villa, typical of Andalusia, with large windows and whitewashed walls—ideal for keeping cool. We joined a tour and were shown around the house, which has a piano that Lorca would play on (he was a gifted musician, and friends with Manuel de Falla), as well as a desk at which he wrote.

The hour-long visit gave a satisfying overview of the many facets of his short life. Lorca came across as a man wholly devoted to the arts—to music, to poetry, and above all to theater. One of my favorite items on display was a poster for La Barraca, a popular theater group that he helped to direct. They would travel around the countryside and perform for the benefit of the public, putting on avante-garde shows for the masses. It reminds me somewhat of the Federal Theater Project of the American New Deal, and demonstrates that Lorca, while not overtly political, did not shy away from social causes.

Our next stop was the small town of Fuente Vaqueros, which is a short drive from Granada. There, we visited the house where Lorca was born and spent his earliest years. It is a large house with thick walls, ideal for keeping out the heat. We were given a tour—just the two of us—by a local whose grandfather had gone to the same primary school as Lorca himself! He explained that the Lorca family was quite wealthy, having made their fortune in the tobacco business. Indeed, their house was one of the first to receive electricity in the area.

The upstairs of the house was made into a small exhibition space. Among other things, there is the only extant video clip of the poet, as he emerges from a truck used to haul theater supplies. The video has no sound and it lasts for only a few moments. Yet it is a tantalizing glimpse into the past. Also on display are puppets that Lorca made, in order to put on shows for his baby sister.

A short drive from Fuente Vaqueros is the town of Valderrubio, previously known as “Asquerosa” (“Disgusting”). Apparently, this name is a linguistic coincidence, having come from the Latin Aqua Rosae (“Pink Water”), but it led to the unfortunate toponym “asquerosos” for the denizens of this perfectly inoffensive town. Here is yet another house museum of the playwright, this one larger and grander than the one in Fuente Vaqueros. Unfortunately, however, we arrived too late for the tour of this house, and had to content ourselves with a quick walk-through.

But we were on time for the tour of the House of Bernarda Alba. This is an attractive villa next to the Lorca property, where a widow lived with her daughters. Federico used this family as the basis for one of his best plays, La casa de Bernarda Alba, which is about a tyrannical widow who imposes a decade’s long period of mourning on herself and her daughters after the death of her husband. Apparently, the actual family—who I presume weren’t nearly as monstrous as Lorca portrayed them—were understandably quite offended by this, and cut off contact with the Lorcas. And now, to add insult to injury, their home stands as a museum to the poet’s honor!

Our last stop was rather more somber. On the 19th of August, 1936, Lorca was arrested, taken outside the city, and shot. Against the advice of his friends, on the eve of the Civil War he had traveled to his native city. But as war broke out and violence spread, he realized that he was unsafe and so hid himself in the home of family friends, who were members of the right-wing Falangist party. The political connection didn’t help. Along with three other men, he was taken to a spot on the highway between Vïznar and Alfacar and shot.

The place where Lorca was executed is hardly recognizable today. At the time it was a barren hillside, completely devoid of vegetation. Today, however, it is a grove of tall pine trees that cover the ground with shade. We parked the car and walked up a hill, not sure what we were looking for. Then we noticed papers tacked onto trees, like ‘Lost Cat’ posters on telephone polls. They were photos of the people believed to be executed here. There were dozens of these photos, each one with a name, profession, and believed date of death.

Even more unsettling were the white tents, standing empty and silent. They were covering excavation pits, where investigators are finally unearthing the remains of the hundreds of victims executed here, nearly a century after the Civil War. The investigators are also collecting DNA samples from surviving family members, so as to be able to identify any remains they uncover. Lorca’s body is believed to be here somewhere, though it hasn’t been identified yet. (You can learn more about the effort by following the groups’s Instagram.)

To state the obvious, it is chilling to think that such a harmless man—a gift to the world and an ornament to his country—could be deemed so threatening that he had to be executed this way. His last moments must have been terrifying. His work, however, has outlived Franco and his regime, and perhaps it will outlive the current constitution.

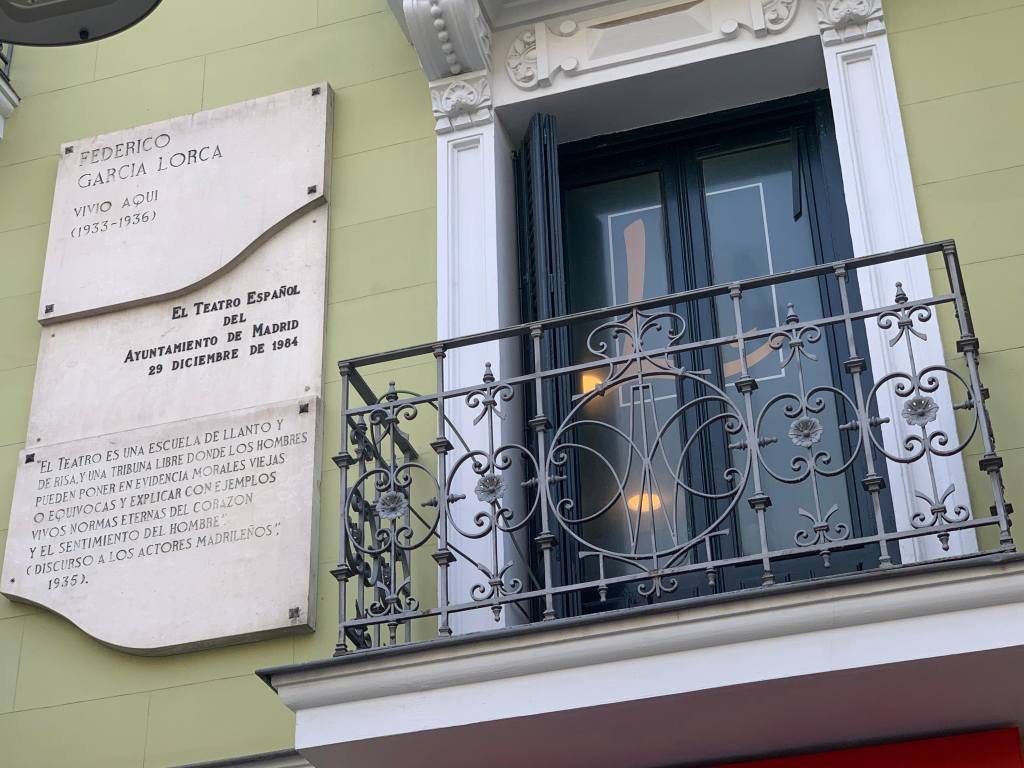

Now, for the very serious Lorca fan, there are also some sites to visit in Madrid. There is a lovely statue of the poet in the plaza de Santa Ana, and on Calle de Alcalá 96 there is a plaque which marks the apartment where Lorca lived for the last three years of his life. Another worthwhile visit is the Residencia de Estudiantes, where Lorca lived as a student along with his Dalí. The two were very close as young men, though many have criticized Dalí’s later reconciliation with the Francoist regime as a betrayal to the memory of his friend.

But, of course, the most important thing is not to follow in his footsteps, but to keep reading and performing his works. This way, he will remain forever alive.

Monet: Giverny, L’Orangerie, Mormottan

The name of Claude Monet stands over the artworld like a colossus—the man who defined one of the most iconic movements in art: impressionism. For a great many, I suspect, these blurs of color and light are what immediately spring to mind when they imagine the French countryside. The image of the paint-stained artist, brush in hand, standing in a field of grass, flouting both artistic conventions and social norms, is virtually a cliché now. But all of this we owe to Claude Monet.

Stereotype or no, I admit that this vision of the artist has a certain romantic appeal to me. And so I decided, on my last trip to Paris, to pay a visit to the home of this artist to partake of this dreamy, wistful aesthetic.

Normally, getting there from Paris is no challenge. A high-speed train bridges the distance in less than an hour—departing from Gare Saint-Lazare, a station Monet depicted in a series of paintings, and then arriving in the town of Vernon. This town lies just across the river Seine from Giverny. A taxi, a bus, or even a sprightly walk will get you to Monet’s house in no time.

But I was unlucky. During my trip, in May of 2024, there was maintenance scheduled on this particular train line, so this option was out. So I opted for something I habitually avoid: a guided bus tour.

The bus was set to depart early in the morning, from the Avenue de la Bourdonnais, in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower. However, there was a hitch. As the group of tourists—speaking a babble of tongues—gathered on the pavement to board the bus, a police officer approached the tour guides and explained something with authoritative insistence. Apparently, the bus could not park in its usual spot, because of the new rules put in place in preparation of the summer olympics.

The preparation was already apparent. The Champs de Mars was buried in a mass of scaffolds, and a large stage was nearly finished in the Trocadero on the other side of the river. What this meant for us, however, was that we had to walk to a street a few blocks away. As we walked, a young Italian woman, who spoke astoundingly good English, chit chatted with an elderly American couple; but I was too focused on Monet for smalltalk.

The bus swept us out of the city and into rolling fields of green. We were headed north, towards Normandy. On the bright May morning, it was easy to imagine why this gentle, domesticated landscape inspired artists to capture its delicacy.

We arrived in no time, and I followed the crowd into the property. This was a moment I had imagined to myself many times. Monet’s gardens are a kind of mythical place in the world of art, a place I had seen through Monet’s eyes innumerable times, imbued by his vision with mystery and translucent beauty. It was almost a surreal moment, then, when I realized that I was standing in the gardens, and that they were real, physical, concrete.

The gardens are divided into two sections. Directly in front of the simple house, with its pink plaster walls and vine-covered trellises, there are rows of flowers in square plots. They are arranged like globs of paint, splashes of color that look organized from afar but haphazard from up close. It is impressionism made manifest.

The more famous section of the garden is on the other side of the highway that runs through town. Monet purchased this property later, which is why it is not contiguous with the original gardens. Visitors nowadays can pass from one to the other through a small underpass under the road, but Monet himself would have had to cross it.

If the first section embodies the lightness and prettiness that is often associated with impressionism, this one is its highest embodiment. Here, Monet expressed his love for Japan, with the thicket of bamboo, the famous pond of water lilies, and the green wooden bridge. The pond is shallow and murky, and ringed all sorts of trees, bushes, and flowers. As a result, the surface texture is a mixture of reflections—of the blue sky, grey clouds, and the surrounding gardens—and the waterlilies lurking below. Though I was there briefly, it took little imagination to picture how the surface could change with the time of day, the weather, and the seasons. It is a kind of laboratory to study color and light.

I would have loved to have basked in the garden for hours, but my time was limited by the tour bus schedule. So I pulled myself away to queue up for the house. It is much as one might expect of Monet—open, light, airy, and unpretentious. Unfortunately, however, it is difficult to put oneself in the artist’s shoes and imagine oneself at home, if only for the constant crowds pushing the visitor from room to room. But I still had a few moments to appreciate Monet’s fine collection of Japanese prints.

The visit ends, as so many do, in the gift shop. Yet unlike so many gift shops, this one is actually one of the main attractions. Though it looks like a large green-house, this was actually Monet’s studio—and it is easy to see why, as the large windows in the ceiling flood the space with light. Perhaps it is sacrilegious to fill such a space with knick-knacks for tourists; yet, as far as knick-knacks go, the items on display are surprisingly enticing, if only because they are adorned with the master’s paintings.

If I had more time in Giverny, I would have walked the short distance to the Église Sainte-Radegonde, where Monet is buried in a family plot. I would also have liked to visit the small Museum of Impressionism, which has a collection of paintings by Monet and others. But, alas, my tour bus was departing for Paris, and I didn’t have any more time to spend in Giverny.

When I got back into the city, I decided to round out my Monet experience by visiting the Musée Marmottan. This is located near the Bois de Boulogne, a huge park to the west of the city. The museum has one of the finest Monet collections in the world, mostly thanks to a huge donation by Michel Monet, the artist’s only heir. It is housed in what used to be a Duke’s old hunting lodge; and like the Frick Collection in New York, it preserves some of the ambience of obscene wealth.

The museum has a series of rotating special exhibits (when I visited, it was about art and sport) and a collection of impressionists that goes far beyond Monet. But his work is the main attraction. The paintings are held in an underground space, modeled after another museum in Paris, the Musée de l’Orangerie—with large, open, well-lit rooms which situate the viewer in a kind of simulated garden.

And, indeed, standing there after paying a visit to the real garden gives you a wonderful insight into the way an artist’s eye can both capture and transform its subject. Monet’s paintings are both highly “unrealistic”—impossible to mistake for a photograph, say—and yet startlingly accurate. They convey subtleties of light and color that a more “correct” technique would overlook. Or rather, they convey a kind of flavor—a subjective sensation, overlaid with aesthetic appreciation.

The only disappointment of my visit was that the museum’s most famous work, Impression, Sunrise, was away on loan. This work, which Monet completed in 1872, was monumentally influential; it would eventually give the entire artistic movement its name. The painting was both daringly original and a continuation of trends that came before. Its originality is apparent when compared to the oil paintings of the established French artists of Monet’s day, with their impeccable technique and focus on mythological or allegorical subjects. Monet’s work is nothing like that. But a side-by-side comparison with, say, a Victor Turner painting shows how Monet took pre-existing techniques for portraying light and atmosphere, and then expanded on them.

The last museum I want to discuss is one I visited many years before this trip, before even the 2020 pandemic: the Musée de l’Orangerie. This museum is in what used to be an “orangery,” a building to protect orange trees from the harsh Paris winter. In the past, you see, oranges were something of a royal prerogative—so delicate that only the huge resources of the monarchy could keep them alive in European climes. This particular orangery is located in the Tuileries Garden, and is the home of Monet’s most impressive works.

The visitor enters and almost immediately finds herself in an oval room, flooded with white light. Running along either wall are huge canvases, the Water Lilies—so big that you can easily imagine that you are visiting Monet’s home in Giverny. They are mesmerizing: exuding an almost mystical intensity. In their own way, these paintings are as ambitious and monumental in scope as any in art history; and yet, they are concerned with something completely ordinary. What makes them so powerful is the intensity of vision that Monet brings to the scene, as if he is somehow penetrating the surface layer of reality and looking at its essence.

I remember sitting on the central benches a long time, and willing myself to extract as much from the paintings as I could. I tried to imagine what it would be like for me to have such a vision, to see light and color as pure attributes of nature, rather than mere signs of material things. What I’m trying to say is that these paintings struck me as being wonderfully profound, in a way that very few paintings do. But then again, perhaps I just like pretty pictures.

Well, that rounds out my Parisian Monet experience. While I’m sure his work is not to everybody’s taste—with its focus on pure aesthetic qualities instead of content—I think that Monet has earned his place in the pantheon of artistic greatness. His career was intensely innovative, and he nurtured his creativity into his old age. Unlike so many artists, it is Monet’s final works which have arguably become his most celebrated. Further, I think his art is especially relevant now, as the contemporary art world—with its emphasis on message over form—has moved so radically away from the principles he embodied. This is not to say that either camp is correct, only that Monet’s vision of art is one that is worth getting to know.

I was on Spanish National Radio!

Hello!

I was recently interviewed about my new book on English version of Spanish National Radio (RNE)! You can listen to the interview here (it begins at around minute 10). It’s painful for me to listen to my own voice, but I hope it’s not too grating for you!