The Conquest of New Spain by Bernal Díaz del Castillo

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

In the introduction to this book, its translator J.M. Cohen makes a point to emphasize how badly it is written. This is hardly normal for a book that is widely considered to be a classic—though perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise for a document composed by a poorly-educated soldier of fortune. For this edition, Cohen trimmed much of what he considered to be repetitive, and straightened out some of the knottier prose. Even after this treatment, however, a great deal of this book is a confused and monotonous narration of battles.

And yet, it is an absolutely fascinating document. Díaz wrote his account as an old man, to correct some of the earlier stories about the conquest of “New Spain,” which glorified Cortés at the expense of his followers. This would seem to indicate that Díaz—who was one of these followers—had a proverbial axe to grind. But Díaz’s lack of intellectual subtlety, his clumsiness as a writer, and his obvious frankness combine to make this document strangely absent of perceivable bias. Writing down what he witnessed was such a chore in itself, the reader feels, that Díaz did not have it in him to twist the story to his ends.

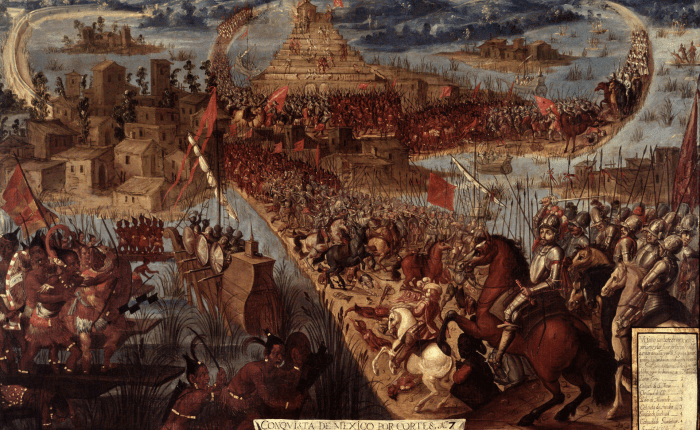

The result is an eyewitness account of one of the most monumental events in human history—the collapse of a great empire, and with it the only power in Central America capable of resisting the Spanish colonists. It is a story rich in drama and intrigue, as Cortés navigates the politics of his Spanish backers (who turn on him) as well as the local peoples he encounters, seeming to stay one step ahead of trouble through his cunning and a generous amount of luck.

It is also a gruesome and tragic story. Hardly a page goes by in this book without armed conflict and human butchery. It is impossible to root for the Spaniards as they slash and burn their way through the landscape, provoking unimaginable losses to our cultural heritage in the process. And yet, ironically, Díaz—an agent of this civilization’s destruction—was one of the last people to see it at its full splendor, and is now one of our best sources of information on what he helped to destroy.

The passages about the Aztec cities, and especially meeting Montezuma in Tenochtitlan, are easily my favorite part of the book. Despite their selfish and bloody purpose, Díaz and his fellows were absolutely dazzled at the splendor of the empire. He was amazed at the broad and straight causeway, the network of canals and bridges, the high stone pyramids. The vast markets, teeming with alien plants and animals, he compares favorably to those of Constantinople or Rome; and he goes into raptures at the beauty of their gardens. The sheer number of people is shocking for the modern reader, who may be accustomed to thinking of the New World as only lightly populated at the time of European contact. On the contrary, Tenochtitlan would have dwarfed the London or Seville of the time.

A tone of regret or remorse creeps into the writing at this point, as if he is sorry that such a wonderful place was destroyed. It is an especially striking tonal shift, given that so much of the book is one battle after another, often told quite matter-of-factly. In another passage, Díaz seems to be amazed that all of this really happened, and seems unable to explain how it could occur, deciding that it must have been divine intervention. This is somewhat self-serving, to be sure, but it does give a taste of his complete lack of guile. As an author, he writes what he remembers, and shrugs his shoulders at the explanation.

What continually strikes Díaz—and undoubtedly his readers—is the prevalence of human sacrifice in the Aztec world. He describes finding people in cages being fattened for sacrifice, temples covered in blood, and the horrifying way in which victims would be dragged up the temple steps and have their chests cut open. As far as I know, there is no reason to doubt that this really happened. Yet it also serves rhetorically as a constant justification for the Spaniards’ actions. It is difficult to feel bad for the Aztecs, after all, if they are murdering on such a scale.

But I think it is important for the modern reader to keep in mind that Díaz and his fellows were hardly there on a humanitarian mission. These conquistadors—who would go on to commit violence on a much larger scale—were there for personal enrichment above all else. The lives of the peoples they conquered had little interest or value for them, beyond their possessions or their enslavement. To pick just one example, after expounding on the horrors of human sacrifice, Díaz calmly relates: “we dressed our wounds with the fat from a stout Indian whom we had killed and cut open, for we had no oil.” I do not say this to re-litigate the past, only because I think this book is more profitable and compelling if not read as a story of heroes and villains.

So while I cannot call this document a literary masterpiece, or even well-written, I found it to be a window—and a surprisingly clear window—into one of history’s great moments. And the sad truth is, to learn about this moment, we must turn to books like these, for “today all that I then saw is overthrown and destroyed; nothing is left standing.”