2025 on Goodreads by Various

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

2025 was a year of upheaval for me. Virtually everything changed: my job, my relationship, and even my country. Strangely, this has been true for many of the people I know (my theory is that the stability we cobbled together during the pandemic is finally unwinding). In any case, this didn’t leave as much room for reading, which is a pity. Even so, the books I did read provided comfort and guidance in these strange times, for which I’m grateful.

New York City was a major topic of my reading. I kicked off the year with The Works, an excellent book about how the city gets its electricity and water, how it gets rid of its garbage, how it controls traffic and moves its citizens. Even more revelatory was Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, by Samuel R. Delaney, which explores the ways that cities promote or discourage genuine human contact. Ottessa Moshfegh’s superlative novel, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, manages to shed just as much light on what it is like to live in this strange place.

Apart from this, my reading was kind of a mixed bag. Esther Perel’s two major books on long-term relationships were extremely interesting for her wide and somewhat unconventional perspective. Vicky Hayward’s translation of an 18th century Spanish cookbook managed to be one of the most fascinating works of history that I’ve encountered in a long while. David Grann’s books—on the Osage murders and Percy Fawcett’s quest to discover the Lost City of Z—were both thrilling; and I continued my slow exploration of Murakami’s fiction.

But the most significant event of my year in books was the publication of my novella, Don Bigote. Thanks to the editors at Ybernia, Enda and María, I even had my first book event, and got to talk about my writing in public for the first time in my life. To top it off, I contributed two chapters to a book about living in Madrid, Stray Cats—ironically, just in time to decide to move away from that lovely city. In a year in which I often felt low and lost, these accomplishments helped to get me through.

Yet perhaps my favorite moment was being able to meet and interview Warwick Wise, whose writing I greatly admire, and whom I met through Goodreads. Even after all these years, then, this site continues to enrich my life.

View all my reviews

Month: December 2025

Review: Persians, by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones

Persians: The Age of the Great Kings by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

This book begins with a great promise: to correct the distorted view that so many of us have of the Persian Empire. This distortion comes from two quite different directions.

In the West, our view of the Persian Empire has largely been filtered through Greek sources, Herodotus above all. This is nearly unavoidable, as the Greeks wrote long and engaging narrative histories of these times, while the Persians—although literate—did not leave anything remotely comparable. Yet the Greeks were sworn enemies of the Persians, and thus their picture of this empire is hugely distorted. Taking them at their word would be like writing a history of the U.S.S.R. purely from depictions in American news media.

The other source of bias is from within Iran itself. Starting with Ferdowsi, who depicts the Persian kings as a kind of mythological origin of the Persian people, the ruins of this great empire have been used to contrast native Persian culture from the language, religion, and traditions imported by the Muslim conquest. In more recent times, Cyrus the Great has become a symbol of the lost monarchy, a kind of secular saint—a tolerant ruler, who even originated the idea of human rights. This purely fictitious view is, at bottom, a kind of protest against the current oppressive theocracy.

But this book does not live up to its promise. To give the author credit, however, I should note that the middle section of the book—on the culture, bureaucracy, and daily life of the empire—is quite strong. Here, one feels that Llewellyn-Jones is relying on archaeological evidence and is escaping from the old stereotypes. The epilogue is also a worthwhile read, detailing the ways that subsequent generations have used (and abused) the history of this ancient power.

Yet the book falters in the chapters of narrative history. Here, Llewellyn-Jones is forced to rely on the Greek sources, and as a result many sections feel like weak retellings of Herodotus, with a bit of added historical context. Even worse, there are several parts in which I think he is not nearly skeptical enough regarding the stories in these Greek authors. At one point, for example, he retells the story of Xerxes’s passionate love affair with the princess Artaynte—a story taken straight out of Herodotus, and which has all of the hallmarks of a legend. That Llewellyn-Jones decides to treat this story as a fact, and does not even gesture towards its source, is I think an odd display of credulity in a professional historian.

The irony is that the final section of the book—full of scandalous tales taken out of Greek authors, depicting the decadence and depravity of the Persian court—only reinforces the very stereotypes that Llewellyn-Jones sets out to destroy. The really odd thing, in my opinion, is that there are no footnotes or even a section on his sources, so the reader must take him at his word—or not. I suspect this omission is to cover up the embarrassing fact that he relied so heavily on Herodotus.

This is a shame, as the Persian Empire does deserve the kind of reevaluation he proposes. It is fascinating on its own terms, and not just as a foil to the noble Greek freedom-fighters. Still, I think this book is a decent starting point for anyone interested in the subject. One must only read it with a skeptical eye.

View all my reviews

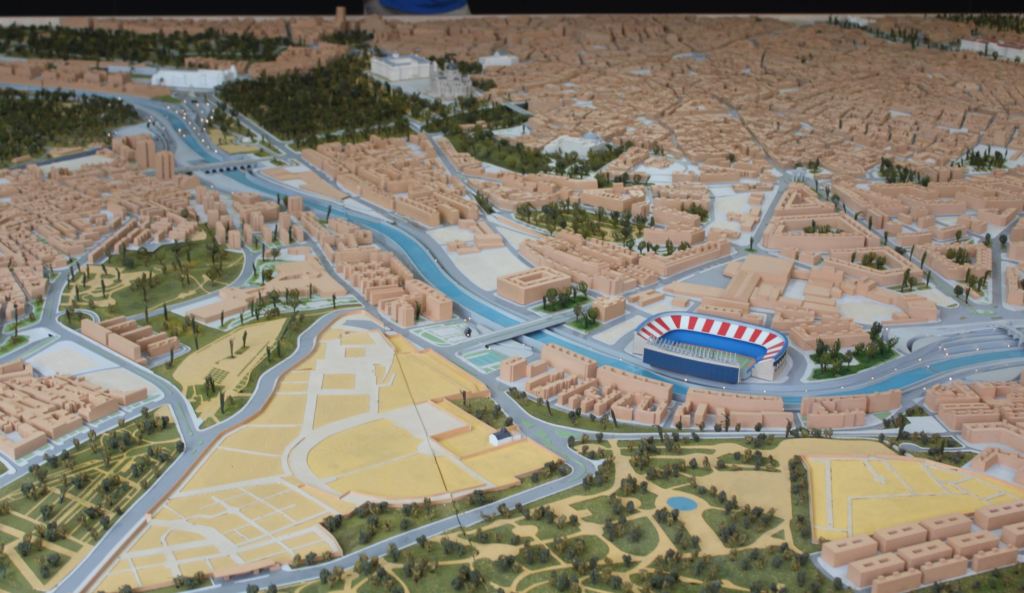

The Madrid Río and the Matadero

One of the immediate charms of Madrid is how relatively compact its historic center is. A visitor can easily walk from the Retiro Park, to the Prado, to Gran Vía, and to the Templo de Debod in the course of a day. Explored this way, Madrid is experienced as a series of unfolding streets, plazas, and monuments, winding and criss-crossing their way across a relatively flat landscape. And yet, to get an idea of the contours of the land, of the natural environment that the city inhabits, one must venture further—to the Madrid Río.

This is a park that runs along the Manzanares River. “River” is a generous term for this trickle of water. Originating in the high sierra, the Manzanares runs southward, eventually emptying into the mightier Jarama River. As a natural resource, it is almost negligible—far too shallow for boat travel, and far too scanty to be a significant source of drinking water. But it is this slight river, working over the course of centuries, which carved out the high bluff upon which the Royal Palace is now situated, and which formed the core of the original settlement of Madrid. In other words, it is because of the small valley created by the Manzanares that anyone thought of settling here in the first place.

And the Manzanares has never lost its importance. It makes an appearance in many of Goya’s paintings, as a kind of pleasure ground, where aristocrats dressed as majos and majas took their leisure. During the Spanish Civil War, this humble river formed an important line of defense for the city. And during this century, the Madrid Río was the site of a major project of urban renewal.

For years, you see, this trickle of water had been sandwiched between the two directions of the M-30, the circular highway that was built in the 1960s to alleviate congestion in the city center. With three lanes of traffic on either side, the Manzanares could no longer be enjoyed by the madrileños.

Yet this changed in the early 2000s, when control of the highway was passed to the local city government, who soon decided to move this section of the highway underground. As you might imagine, this was a massive project, costing several billion euros; and it resulted in the longest network of traffic tunnels in Europe.

But it was worth it—for the burial of the highway solved many urban problems at once. Most obviously, it helped to alleviate some of the noise and pollution of the passing traffic. What’s more, the project re-connected neighborhoods that had been cut in two by the highway, weaving the city together again.

But the most precious result of this project was, I think, the restored access to the Manzanares River. This is no small matter. In a city lacking in any conspicuous natural features, the humble Manzanares is one of the only things that ties the city center to the landscape. And the good citizens not only got their river back, but a wonderful park to boot. Stretching for miles on either side of the river, the Madrid Río Park was created on the surface of the highway tunnels—and it is now one of the treasures of the city.

For the most part, this park consists of walking, jogging, and biking paths that run parallel to the course of the river. Shade is, admittedly, something of a problem in the hotter months, as the recently-planted trees haven’t had time to grow to their full splendor yet. Still, for such a narrow park, surrounded on both sides by apartment buildings, it can feel remarkably peaceful and quiet. Traffic passes over and under, largely out of view.

The park is notable for the many attractive pedestrian bridges that connect its two sides. There are the two “shell bridges,” near the Matadero, with lovely paintings on the inside. The aptly-named Puente monumental de Arganzuela is an enormous spiral that swirls across the river. A favorite of mine is the Puente del Principado de Andorra, which is a kind of faux-railway bridge, made with crisscrossing iron beams, but which splits apart to form a triangle.

The most beautiful, by far, is the Puente de Toledo—a stone bridge built in an ornate Barroque style. It emulates the far older, and more historically significant, Puente de Segovia. Built in the 16th century, this was the first major bridge to span the Manzanares river. It was mentioned frequently by Spain’s Golden-Age poets—though, admittedly, often in a humorous vein, for being so enormous in comparison with the stream it spans. It is a bridge in search of a river, mucho puente para tan poco río.

I want to mention here something puzzling to many visitors. At several points along the river there are what appear to be Greek columns. They look old and weather-beaten, and at first I wondered if they were genuine remains of an old temple. But their placement—much too far apart to belong to a single building—seemed to eliminate that possibility. The truth is that these are not columns at all, but ventilation shafts. You can prove this for yourself if you observe them from above: they are hollow inside.

You see, one of the reasons it was originally decided to canalize the river was that it was becoming a hazard for hygiene. As sewage continually drained into the Manzanares, it became an open cesspool. Thus, underground channels were made to divert contaminated groundwater. These channels had to be ventilated, to prevent pressure from building up, and the air shafts were disguised as Greek columns. If you look closely, you will notice that some of them still bear the scars from bullets and shrapnel from the Spanish Civil War.

Apart from its bridges, the river is also crossed by several dams—seven, to be exact. In the past, these were used to build up the waters of the Manzanares to a respectable level, allowing the citizens to swim and even the local rowing teams to practice. Yet this was not good for the wildlife—trapping fish, and flooding the many habitats adjacent to the river.

A major decision in the creation of the Madrid Río park was the opening of the dams, allowing the river to return to its natural state. This rewilding has created a surprisingly vibrant ecosystem in the sandy banks of the river, where plants and animals thrive. Especially happy are the birds, which have flocked to the area. Now, a visitor can see an astounding variety of species, from nile geese to herons to cormorants. (The rowing team, on the other hand, have been left up the river without a paddle.)

The Madrid Río is also home to some cultural sights. The Ermita de la Vírgen del Puerto (Hermitage of the Virgin of the Harbor) is a rather severe brick building from the early 18th century, where madrileños like to practice salsa dancing. Nearby is the Ermita de San Antonio de la Florida, a church decorated by Francisco de Goya, which also serves as the painter’s tomb. (Across the street is Casa Mingo, a classic restaurant serving roast chicken.) Further down is the Puente de los Franceses, a railroad bridge built by French engineers, which served as an important point in the defense of Madrid by the International Brigades during the Civil War.

Yet the most significant cultural landmark along the river may be the Matadero. The word matadero is simply Spanish for “slaughterhouse,” and that is exactly what this building complex used to be. In the past, you see, there were commercial livestock pens and slaughterhouses in the city center. But as the city grew, it was decided that this was both inadequate and unhygienic. Thus it was decided to build a large municipal slaughterhouse in what was then the outskirts of the city. After a lengthy planning period, and over a decade of construction, the Madrid Matadero opened in 1925.

The Matadero is a complex of nearly identical buildings connected by walkways and courtyards. Each building was originally for a different purpose. Some were pens to hold living animals, others were for the act of killing. Some were for cattle, others for pigs, and others for chickens. And of course there were processing facilities, too, where the meat was broken down, divided, salted, preserved, boiled, and so on. One can only imagine the stench.

Much time and care was spent in making this facility both attractive and efficient. Yet the city quickly overtook the scope of the original design. As the Matadero got swallowed up in the expanding urban center, it was no longer isolated from the populace. What is more, a part of it had to be demolished to make way for the aforementioned M-30 highway, further limiting its use. Most of all, however, the facility was simply not big enough, nor modern enough, for the new Madrid. By the 1970s, the Matadero ceased its original function, and nobody was quite sure what to do with it.

Luckily, it was ultimately decided not to demolish these buildings, but to convert them into what they are today: a cultural center. It was an inspired choice, as the architecture of the Matadero is astoundingly lovely. Built in a neo-Mudéjar style—with bricks, stonework, and tiles—the buildings seem almost festive with their pointed roofs. One wonders why such a place was made to look so pretty, as it must have been nauseatingly grim while it served its original function. Now, however, it is positively inviting.

It is difficult to enumerate all of the things that the visitor can see and do at the Matadero. They have theater performances, both contemporary and classical, both inside and outdoors. There are photography and art exhibits; and the cultural center is the permanent headquarters of the National Dance Company. There is even a small movie theater showing artsy films. Added to this, the Matadero hosts various events throughout the year, from concerts to seasonal markets, from comic book conventions to ice skating rinks and theme park rides. With its bar and café, it is a remarkable resource for the madrileño looking for a bit of culture.

Next to the Matadero is an attractive group of yellow apartment buildings that surround a central courtyard. This is the Colonia del Pico del Pañuelo, built to provide affordable housing for the workers of the Matadero. Its name (“the point of a handkerchief”) comes from its form: from above, it looks like a folded piece of fabric. Made of reinforced concrete, the workers’ colony is nevertheless quite picturesque, and has been featured in several films. Nowadays, however, it is not quite so affordable.

I also want to mention another nearby attraction, the Crystal Palace of Arganzuela. This is a large greenhouse next to the Matadero. Free to visit, the greenhouse has four separate areas corresponding to different climatic zones. It adds a bit of natural wonder to the cultural attractions next door.

After discussing all of this history, and all of these landmarks, I fear that I am still not doing justice to the real charm of these places. The Madrid Río is, above all, a park—and a good one. Flat and scenic, it is ideal for a lazy bike ride or a long run—or just for sitting on a bench and watching the locals stroll by. There is a football field and a skate park, and several cafés and kiosks where the visitor can have a cold beer under the blue sky. The Matadero is special for being a cultural space that is primarily for the madrileños. One doesn’t have to wait in line with hordes of tourists here—and I hope it stays that way.

And the Madrid Río keeps going. If you follow the river south, you go through the Parque Lineal de Manzanares, an oddly futuristic park, where you can admire Manolo Valdés’ monumental statue of a woman’s head. Go further along the river, and the city is left behind completely. You find yourself in the arid countryside of central Castille, where storks nest in giant colonies and caves perforate the cliffs overhead. This is where I would go on my long runs, savoring the sliver of green that is the river, as it cuts through the yellow landscape. After an hour of running, the city would seem like a distant memory, somehow swallowed up in the shallow waters of the Manzanares.

The Blog Turns 10!

Today marks the 10-year anniversary of the first ever post on my blog. A lot has changed since then. At the time, I had just moved to Spain for what was supposed to be a single year. I was 24 years old, and immature even for that age. My Spanish was terrible, bordering on non-existent. And Europe was shockingly new.

The idea of starting a blog came from my habit of writing book reviews. That practice began just from a desire to really keep track of what I learned from all of the books I was reading. There is a famous quote, often attributed to St. Augustine: “The world is a book, and those who do not travel read only a page.” Not well-traveled himself, the good saint almost certainly never said this. Still, in that spirit, I decided that I ought to write up my trips, if only to really suck the marrow out of each experience. After all, I was only supposed to be there a year.

My first post was about Toledo. This was appropriate, as Toledo was the first place I visited in Spain that really astounded me. There is simply nothing in the United States that even remotely resembles the city’s perfectly preserved medieval core—its twisting, narrow streets, its stone bridges and walls, and above all its gothic cathedral.

The grand church was a revelation. Inside and out, the building was simply covered in artwork—statues, friezes, frescoes, and paintings—every inch of it made by hand, over centuries. It wasn’t just that the cathedral was beautiful. It gave me a new concept of time. Even the most negligible adornment would have taken hours, days, weeks of painstaking work.

The structure of the building itself, its stone roof seeming to float above me, seemed almost miraculous. That it could be designed without computers and assembled without machines was a testament to human perseverance, if nothing else. It did to me precisely what it was made to do: make me feel like an insignificant, ephemeral nothing in comparison with the world around me.

It was this experience, above all, that prompted me to write up the visit and to begin this blog. Since then, I’ve published over 700 posts here, including another one about Toledo. Over this time, the purpose and nature of the blog has fluctuated. At first it was meant to be a sort of diary, recording my own experience. Later, I tried to make it more like a travel guide, providing useful information and context to would-be travelers.

Yet I must admit that I haven’t had the discipline to stick to any one concept of this blog. So it is very much a mixed bag—of reviews, essays, short stories, travel pieces, and anything else that I deemed worthy of writing. This lack of an overarching concept has irked me, and I have often chastised myself for being such a self-indulgent writer. But at this point, I can at least say that this blog is an accurate reflection of myself—both my strengths and my shortcomings.

Much has changed during this time. I stayed in Spain far longer than I ever dreamed, spending over a decade in that enchanting country. My Spanish improved to the point where I consider myself nearly bilingual. And Europe went from shocking to comforting, as I saw cathedral after cathedral, city after city, and grew accustomed to the sights, languages, customs, and the different pace of life in that continent.

Change in life can happen so gradually that it is difficult to even notice. But I was given a chance to reflect on my new perspective on a recent visit to Toledo, back in October, nearly ten years after my initial trip. The city was still beautiful, the cathedral still magnificent. Yet I was not transported in the same way as I was. Not that I think any less of Toledo, just that it was no longer an alien world to me. It was home.

Rereading my original post about Toledo is another chance to reflect on this change. Now, I normally avoid reading my old writing, as I find it acutely embarrassing. But I actually came away from this reread with some affection for the Roy of that time. True, he had a lot to learn, and a lot of growing up to do. He was pretentious, often condescending, and took himself far too seriously. But he was curious, he was passionate, and he wanted to improve himself intellectually and even spiritually. He was on the search for wisdom.

I don’t know if the Roy of that time would be pleased with the Roy of today. I’m not always pleased with myself. Certainly I didn’t achieve his dream of becoming a famous writer, though I have gotten a couple books published. In any case, I should thank him; I owe my former self a lot. At a crucial moment in his life, he decided to go on a journey rather than embark on a conventional career. I just hope that I can make proper use of the experience he gave me.

My life changed, once again, on the 20th of October, when I moved back to New York. It was a tough, complicated decision, and of course there is much I miss about Spain. So far, however, it seems to have been the right one. In any case, it does put the future of this blog in doubt. Admittedly, I have a backlog of travel pieces that I want to write up in the coming months. And, hopefully, there are new trips to be taken, and much of the world still to see.

Realistically, though, I imagine that I’ll be doing significantly less traveling in the foreseeable future—especially as I get my career on track here. But, knowing myself, I will find something to write about. I always seem to.

I can’t end this post without thanking everyone who has taken even a passing interest in this blog. Hopefully, we’ll see each other here in another ten years. Until then, cheers!

Review: New Art of Cookery

New Art of Cookery: A Spanish Friar’s Kitchen Notebook by Juan Altamiras by Vicky Hayward

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I did not expect to be going to a book event during my last weekend in Madrid. But when I learned that an author was going to be talking about a historic Spanish cookbook at my favorite bookstore in the city, I decided that I had to make time for it.

I was transfixed from the start. The history of food is, I think, often overlooked—even by history buffs; and yet it provides a fascinating lens through which to learn about the past. In daily life, we are often apt to think of traditional dishes as things that have existed since time immemorial. But this often isn’t the case. In this cookbook, originally published in 1745, you will not find potato omelette, or paella, or croquetas, or cocido, or gazpacho…

Wait, I’m getting ahead of myself. Let me describe what this book is, first. Nuevo arte de la cocina is a cookbook published under the name Juan de Altamiras (a pseudonym) in 1745. It proved to be immensely popular, remaining a bestseller well into the next century. The book’s author—whose real name was Raimundo Gómez—was a Franciscan friar, who grew up and spent much of his life in rural Aragón. This book is a contextualized translation by the English author Vicky Hayward. Throughout the book, she adds a great deal of fascinating historical context, as well as modernized versions of each of the over 200 recipes here.

As you might expect, the book is organized along religious lines, with food for meatless and meat days. Back then, something like a third of the year consisted of meatless days; and during Lent, the pious were supposed to be basically vegan. This makes the book a surprisingly good resource for vegetarian cooking. Yet what made it so innovative in its time was that, unlike so many previous cookbooks, Altamiras wrote for ordinary Spaniards—not courtly chefs. The recipes here are simple home cooking at its finest, requiring basic ingredients and straightforward technique. This was revolutionary at the time.

And to return to my previous point, much of the cooking can seem surprisingly exotic. Altamiras uses sauces made from hazlenuts, almond milk, and pomegranate juice. He mixes citrus, saffron, and tomato, and loves to add cloves and cinnamon to his savory dishes. Hayward was good enough to cook samples for the audience at the book event—several of which made me think of Iranian food. According to Hayward, this is because the Morisco influence (Muslims who had converted to Christianity in the 15th century) was still alive and well in Altamiras’s childhood.

I was also surprised at the wealth of ingredients available to Altamiras. He calls on a wide range of fruits and vegetables, as well as fresh fish—despite not living near the coast. He had eggs aplenty and endless ham and lamb, not to mention nuts, legumes, and spices. Saffron grew locally in his day, and salt cod was a staple (though including such a humble ingredient as salt cod was innovative). Most surprising of all, he made iced lemon slushies by using the snow in the nearby mountains. This was a rich and varied diet.

Hayward has fascinating things to say about all of this—the cooking techniques, the sources for ingredients, the role of religion, the Muslims influence, and so much more. More than so many other history books, this one made me feel transported back in time. And a delicious time it was.

Now, one would think that there could be nothing more innocuous than a translation of an 18th century Spanish cookbook. And yet, the event I went to last month was the first event held in honor of the book—eight years after its initial publication! According to Hayward, this is because her book attracted the ire of the Aragonese government, who were offended that a foreigner had beaten them to the punch in bringing their native son to a wider audience. She reports being attacked left and right by Spanish academics. If this is true, it is very silly.

I left the event in a buoyant mood, glad that I could still be so surprised by Spanish history after so many years. And I celebrated, appropriately, by the orgy of food that is Tapapiés—Madrid’s annual tapa festival, held in the Lavapiés neighborhood. It was a wonderful way to spend my last Friday in the city.

View all my reviews