A crucial moment in the history of Spain was the transition from the Habsburgs to the Bourbons, a result of the War of Spanish Succession. With the French Bourbons came French ideas and sensibilities, among them the mercantilism of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, based on limiting imports and maximizing exports. To foment national manufacturing, the crown created various “royal factories” throughout the country, many of them focused on luxury goods—literally fit for a king.

Not all of these factories survive. The Royal Factory of Porcelain, for example, was destroyed by Wellington’s troops during the Napoleonic invasion of Spain. Nowadays, the curious visitor of Retiro Park may notice only a few scattered ruins of the enormous building. Others have changed function. The Royal Tobacco Factory in Embajadores, for instance, has become a cultural center, known as the Tabacalera (currently closed for repairs).

Yet a handful have retained their original purpose. Among these is the Royal Factory of Tapestries. It is housed in a lovely brick neomudéjar building near Atocha. Visiting is not especially easy. The factory is only open during the week, and only during the morning. To visit, you must write them an email with your ID number and join one of the four daily guided tours. If you are unlucky enough to work during the week, a visit is close to impossible. I went on a hot July day, after school had ended for the summer.

No photos are allowed during the tour, and for obvious reasons. It is still a working factory, full of women (there were only a couple men) weaving industriously. I wouldn’t want to be photographed by legions of strangers either. But this gives the visit a rare intimacy. The weavers sit at enormous, antique looms, their hands in constant motion. Using a pattern, they put together their tapestry stitch by stitch, knotting the thread with a single hand, so quickly and dextrously that it is impossible to follow their motions. It is both beautiful and, I imagine, incredibly dull, as they patiently put the tapestry together millimeter by millimeter, day after day, week after week.

The curious reader may be wondering who on earth is ordering and paying for these tapestries. They wouldn’t fit in most homes and, besides, are a bit old-fashioned as decoration. The commissions come from museums and other historical institutions. The tapestries I saw, for example, were for a German palace being renovated for visits.

Further on the tour, we were introduced to a resident artist, who was designing an enormous new carpet for the Almudena Cathedral here in Madrid. He held up the design and explained why he had chosen the shapes and the colors—the apparently abstract pattern had a well thought-out logic. Then we were led to the refurbishing wing, where old tapestries and carpets are given new life. The work that goes on here is, I imagine, even more painstaking than the new commissions. If memory serves, the factory is even equipped with a kind of enormous pool used to gently wash antique fabrics.

The other royal factory I have visited is located somewhat outside Madrid, in the province of Segovia, in the town of La Granja de San Ildefonso. This town is more famous for being the site of an enormous royal palace—one of the finest in Spain, complete with gardens that emulate (if not exactly rival) those of Versailles. Yet for my money an even more interesting place to visit is the Real Fábrica de Cristales.

As you might expect, this factory originated to supply windows and mirrors for the royal palace that was being constructed nearby. But it went on to produce high-quality products for more than a century after the palace’s completion. Nowadays, unlike the tapestry factory, it is mainly a museum space, dedicated to both the history and contemporary practice of glass blowing. And it is a fascinating place.

First, the visitor can see an expert glass blower giving demonstrations in the working furnace. As there are usually not many visitors, this can be an intimate experience, separated by just twenty feet from the artist. The temperatures involved are intense, in the range of 1000 degrees Celsius, and it is difficult to see the melting, molten glass without imagining how horrendously dangerous it must be to work with the stuff. It is thus all the more impressive to witness somebody turn this lava into delicate, lovely shapes.

The main factory space is full of old industrial equipment—for making windows, mirrors, bottles, and other products. This is all housed in a large, cavernous, almost cathedral-like nave, whose high ceiling and brick exterior testify to the great risk of fire. Indeed, the factory was intentionally built at a remove from the palace, beyond the original walls of the town, for this very reason. In another room, there is a small exhibit on the art of stained glass; and several stunning examples of the factory’s chandeliers hang from the ceilings.

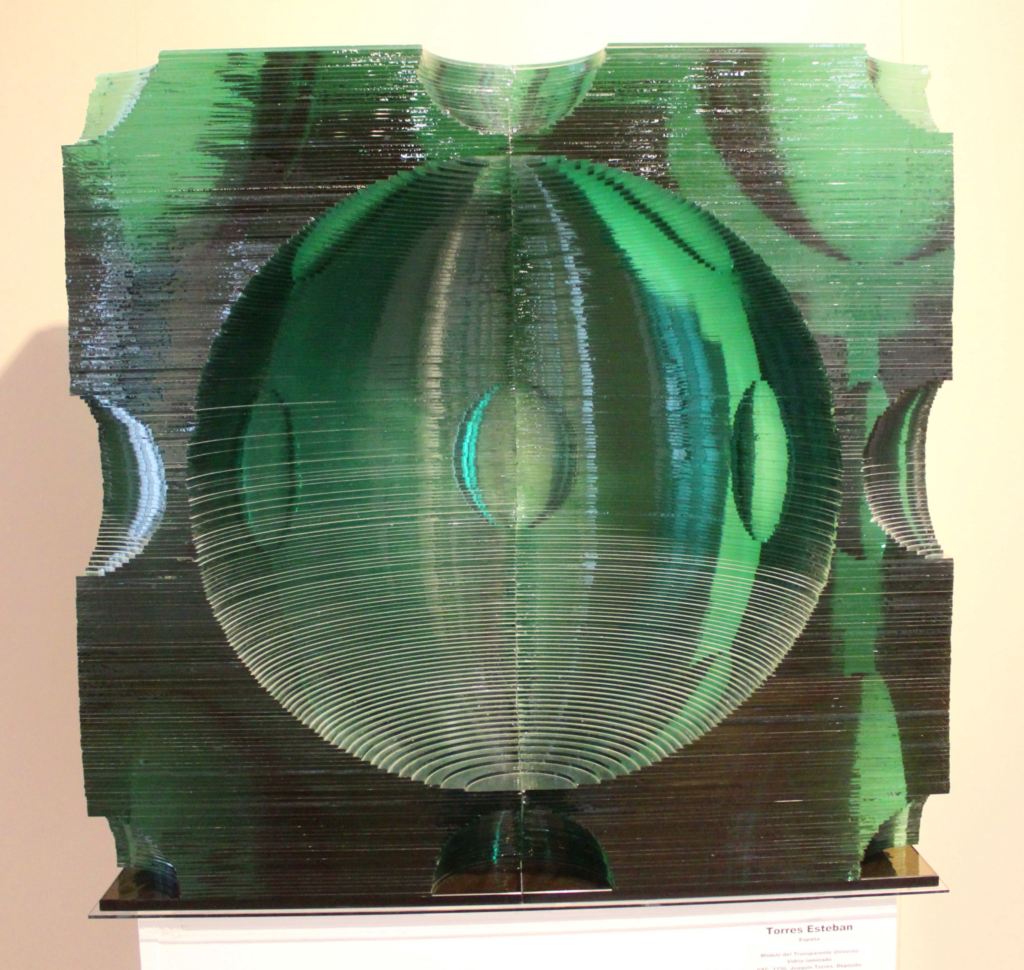

My favorite part of the visit was the section devoted to contemporary art. Here you can see glass shaped, layered, and twisted in ways that hardly seem possible. Particularly beautiful was the work of Joaquin Torres Esteban, whose sculptures as so startling—by turns abstract, mathematical, and precise—that you wonder whether glass is being underutilized as an artistic medium.

In sum, the Real Fábrica de Cristal is my favorite sort of museum: lesser-known, provincial, and yet full of surprises. It is certainly unlike any museum I’ve ever visited. In any case, the royal factories are a fascinating subject for those who, like me, want to go beyond the major monuments. And I’m sure there is a lot more worth exploring.