This is part of a series on Historic Hudson Homes. For the other posts, see below:

- Washington Irving’s Sunnyside

- John D. Rockefeller’s Kykuit

- Alexander Hamilton’s Grange

- FDR’s Springwood & Vanderbilt Mansion

- Thomas Cole’s Cedar Grove and Frederic Church’s Olana

- Jay Gould’s Lyndhurst & Untermyer Garden

It should perhaps come as no surprise that the Hudson Valley is full of the former (and current) homes of the exceptionally wealthy. It is ideally situated to serve as a kind of country retreat for the rich—within a stone’s throw of New York City, but surprisingly green and bucolic.

In the stretch of Route 9 between Irvington and Tarrytown there is a conspicuous concentration of opulent residences. The most famous is arguably Sunnyside, the house of Washington Irving, which now seems like a cottage compared to its neighbors. Nearby is the Belvedere Estate, which once belonged to Samuel Bronfman, owner of Seagram Company, of Canadian whisky fame—though it now serves as the headquarters for the Unificationists, a Korean-Christian version of scientology. And there is also Shadowbrook, a Gilded Age mansion owned by famed jazz saxophonist Stan Getz.

More historical is Villa Lewaro, an Italianate mansion owned by Madam C. J. Walker, the first female self-made millionaire in America—a feat even more impressive considering that she was an African American, living at the turn of the century. She made her wealth by selling beauty products marketed for black women, and then became a noted philanthropist. During her life, Villa Lewaro became an important meeting place for black intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance.

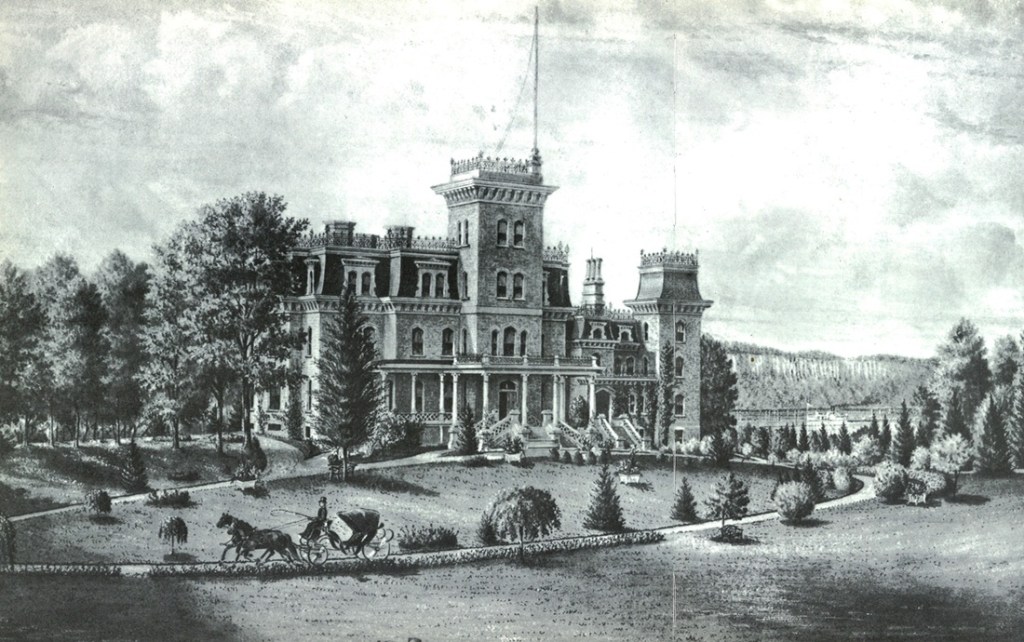

But the grandest of all of these mansions is Lyndhurst. Rising like a misplaced cathedral over the Hudson, Lyndhurst is a spectacular example of neo-gothic architecture. It was first built for William Paulding, mayor of New York City, and a relative of both John Paulding (the Revolutionary War hero who caught the treasonous Major John André) and, through his sister’s marriage, of Washington Irving. Its extravagant style led locals to deem it “Paulding’s Folly,” though the subsequent owner, George Merrit, expanded the house and made it even more fanciful. Both the original house and the expansion were designed by Alexander Jackson Davis, one of the most sought after architects of his day.

Yet the name most associated with Lyndhurst is that of Jay Gould. It is a name that was widely columniated during his life, and his reputation has hardly improved since his death in 1892. Gould was one of the most famous and despised robber barons, who manipulated markets, bribed politicians, and bent and broke the law in order to maintain his dominance. Unlike Cornelius Vanderbilt, say, Gould’s opulence was not due to his founding a useful business. He was more like Warren Buffet than Bill Gates—an investor, not an entrepreneur. Still, in his defense it must be admitted that, like Vanderbilt or Rockefeller or Carnegie, Gould was a self-made man, born into poverty. (Unlike Rockefeller or Carnegie, however, Gould never became a prominent philanthropist.)

Lyndhurst, as it stands today, is much as Gould left it. The visit begins in the old Carriage House, where there is a gift shop, an informational film, and where you sign up for the tour. (The house can only be visited with a guide.) The interior continues the gothic theme of the facade. The ceilings are vaulted, and the narrow windows curve into a pointed arch (making some rooms of the house rather dark). Imitations of gothic tracery even adorn some of the walls. The furniture, too, is in keeping with the severity of the aesthetic, but several lovely examples of Tiffany stained glass do help to alleviate the stuffy atmosphere.

A curious detail, pointed out by the guide, is the use of paint to imitate other materials. While many surfaces appear at first glance to be marble, they are, in reality, painted wood. Meanwhile, the gothic ceilings, window panes, and tracery are made of wood and plaster rather than real stone. This would seem rather counterintuitive, since Gould certainly could afford any medium he wished. But at the time it was considered both fashionable and luxurious to use faux materials. (There is a fine line, apparently, between extreme luxury and garbage.)

The second floor of the house is dominated by a central gallery, which is brightened by the large windows. This is filled with oil paintings—by lesser-known European masters—most of which can loosely be described as 18th century Romantic realism. Among the collection, however, is a rendering of the Jay Gould Memorial Chapel, a beautiful stone church he helped to reconstruct, as well as a study for the Tiffany stained glass windows to be installed in the chapel. There is also a portrait of Gould himself, who always comes across to me as a misplaced barfly, with his unkempt beard and surly expression.

The two opulent master bedrooms open out into this sun-filled art gallery, making a sharp contrast with the dark, almost church-like ground floor. I would feel rather depressed eating in the pseudo-cathedral of a dining room, but quite happy waking up to such a beautiful, open space.

With its strange mixture of neo-gothic, faux-materials, and ersatz religion, Lyndhurst is one of the most memorable of the great Hudson Valley mansions—surpassed in extravagance, perhaps, only by Frederic Church’s Olana. However, as with so many of these great houses, the gardens are ultimately the pleasanter place.

On its great lawn, jazz concerts are held in the summer, organized by Jazz Forum Arts, which hosts performances all along the Hudson Valley. It is crossed by two prominent trails, the Old Croton Aqueduct and the newer Westchester RiverWalk. There, the walker can enjoy the rose garden, which is reliably swarming with bees and other pollinators, and take in the ruins of the old Greenhouse, which once contained over 40,000 plants, but is now just an empty frame.

If you continue walking south along the Old Croton Aqueduct for about two hours—or, alternately, if you drive twenty minutes down Route 9—you will reach yet another grand Hudson estate. This one, however, is conspicuously lacking the mansion. Much like William Rockefeller’s Rockwood, the resplendent Greystone has long since been demolished (leaving only its name in the nearby Metro-North station). But what survived is arguably better than even the finest old residence. It is perhaps the loveliest garden in the Hudson Valley.

I am referring, of course, to the Untermyer Park and Gardens. Samuel Untermyer was another colorful figure from a bygone age. A lawyer by profession, he somehow made his fortune by fighting against corporate interests. He was an enemy of trusts and monopolies, an advocate of stock market regulation, and instrumental in the establishment of the Federal Reserve. He was also, as it happens, an avid botanist, who wanted to create gardens that would outshine even the landscape at John D. Rockefeller’s Kykuit. Thus, he hired the French-trained architect and designer William W. Bosworth—indeed, the same one the Rockefeller’s hired—to make him the finest gardens that money could buy.

The result is something unlike any other garden I have visited. It is surrounded by high walls, apparently in imitation of old Persian models. After passing under two shady weeping beeches, the central waterway leads the visitor’s eye down the highly symmetrical space. In its focus on flowing water, the garden is indeed reminiscent of its Moorish counterparts in the Alhambra, though the wet climate of the Hudson Valley allows for a proliferation of plant life—rhododendrons, lilies, hollies, hydrangea, amid much else—that is wholly unlike its Islamic models. This central space terminates in a large reflecting pool, over which two sphinxes preside.

After exploring this space (the pseudo-Greek Temple of the Sky was closed when I visited), you can walk down the long, cedar-lined stairway to the Overlook. This may be the best spot on the Hudson to enjoy the palisades, as the view somehow presents the illusion of a wholly undeveloped river, with no human habitation in sight. From there, a path leads to another pseudo-Greek edifice, the Temple of Love—sitting on top of an artificial rocky outcropping, from which a stream trickles down. It would, indeed, be a good place to take someone on a date—scenic, romantic, and free of charge.

It is heartening to see the gardens in such fine shape, as they suffered long periods of neglect after Untermyer’s passing in 1940. He wished to will both the mansion and the gardens to the public, but the cost of upkeep proved so daunting that the property was refused by New York State and Westchester County. The city of Yonkers eventually agreed to accept a small parcel of the original estate, though it quickly fell into disrepair and suffered vandalism. In the 1990s, community leaders began advocating for the purchase of more land, and in 2011 the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy started restoring the park to its former glory.

Even now, however, the beautiful gardens are only a shadow of what they once were. During Untermyer’s life, they had sixty greenhouses, tended by sixty gardeners, and was considered one of the centers of botany in the country. Yet what is left is remarkable enough—and all the more remarkable that it is free and open to the public.

5 thoughts on “Historic Hudson Homes: Lyndhurst & Untermyer Gardens”