This is part of a series on Historic Hudson Homes. For the other posts, see below:

- Washington Irving’s Sunnyside

- John D. Rockefeller’s Kykuit

- Alexander Hamilton’s Grange

- FDR’s Springwood & Vanderbilt Mansion

- Thomas Cole’s Cedar Grove and Frederic Church’s Olana

- Jay Gould’s Lyndhurst & Untermyer Garden

Before the advent of “modern art” in the 20th century, the United States was considered something of a backwater as far as painting was concerned. Any American painter with an ounce of ambition had to travel to Paris and spend time copying masterpieces in the Louvre in order to become respectable.

This is precisely what Samuel Morse did. For two years he worked on what was supposed to be his masterpiece, The Gallery of the Louvre, in which he painstakingly reproduced several European masterworks in miniature. This technical tour de force, proof of his hard-earned artistic prowess, earned him—well, very little, which is why he quit painting thereafter and went into the telegraph business. Thus the eponymous code.

Of the American artists who did achieve success during this time, such as Mary Cassat, John Singer Sargent, and James McNeil Whistler, they all spent formative years in Paris and worked in thoroughly European modes.

But one school of genuinely American painting emerged in the 19th century which owed relatively little to the Old World. This was the Hudson River School. This consisted of grand, sweeping landscapes, capturing the relatively (to Europe) wild and untouched countryside. And though artists in this school would eventually paint all over the United States—and beyond—it is named for the place it began: the Hudson Valley.

It took a foreigner to see the beauty in the American landscape, and the potential to turn it into a new sort of painting. Having grown up in grimy, gritty England—in the throes of the industrial revolution—and moved to the United States as a young man, Thomas Cole (1801 – 1848) was deeply impressed by the endless green hills of the Hudson Valley.

Cole arrived in Catskill, New York, in his early 30s, and rented a room in Cedar Grove, the home of the Thomsons, a prosperous local family. A few years later he married Maria Bartow, a niece of the paterfamilias, and made the house his permanent home. What is now the Thomas Cole National Historic Site is, therefore, the ancestral Thomson residence.

The main house is a beautiful building in the Federal-style, constructed in the early days of the nation, with a lovely porch that wraps around the front. The view from the porch is, indeed, worthy of a picture, with the green-blue profile of the Catskills rolling in the distance. It is not difficult to see why the painter chose to live here. While the Catskills lack the dramatic rocky ridges of the great European mountain chains, the soft, undulating green carpet seems to embody the gentleness of nature.

Due to a navigation error, my mother and I arrived late for the “Deep Dive” tour of the house. Still, we got plenty of information. The house is well-conserved and presented. There are reproductions of many of Cole’s letters and journal entries scattered about, as well as several original paintings. The majority of Cole’s paintings portray rugged landscapes where small figures are dwarfed by nature, though at times he included wild architectural fancies, such as a blue pyramid in The Architect’s Dream.

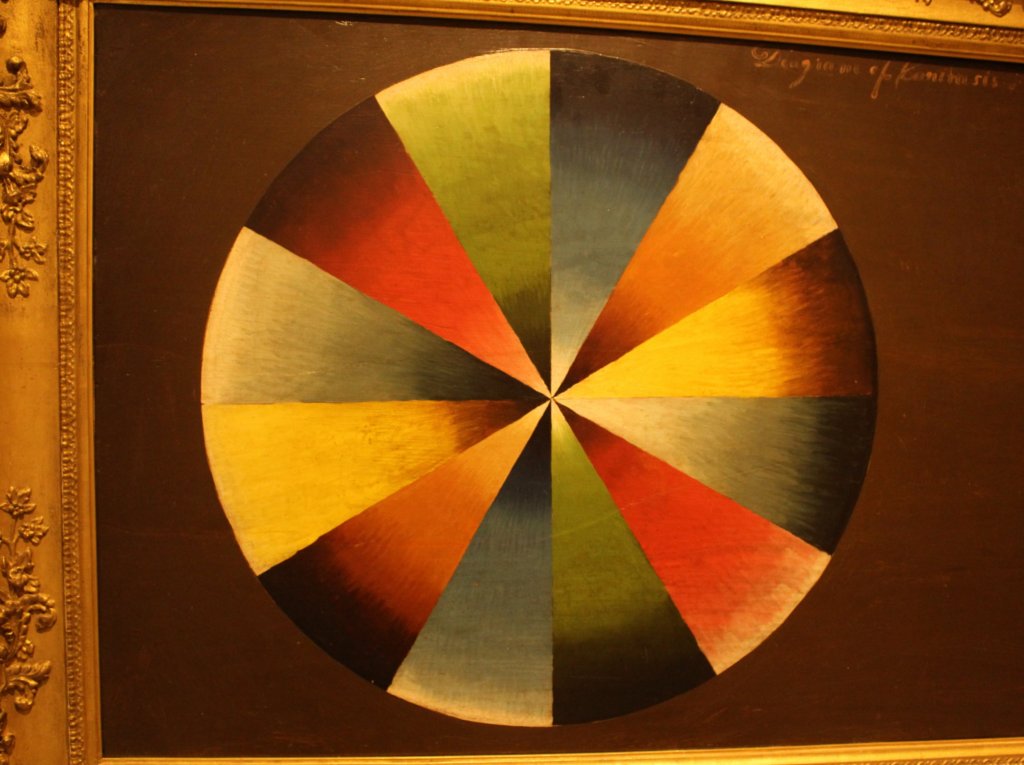

Upstairs, the museum has the last painting that Cole ever worked on, still unfinished. A cloudy blue sky hovers over a featureless brown landscape, revealing the painter’s process—painting from top to bottom. The only clue as to what he intended to paint below are two figures holding a cross, scratched roughly into the paint. Yet still more eye-catching is his Diagram of Contrasts, a color wheel painted over a black background, which looks startling like a work of contemporary abstract art. Indeed, Cole’s description of the work in his diary is reminiscent of Kandinsky:

It is what may be called the music of colours. I believe that colours are capable of affecting the mind, by combination, degree, and arrangement, like sound.

My favorite part of the visit was a video in Thomas Cole’s original studio (a room which he hated, since its only light source was a window facing north). Using his diaries, the museum recreated a hike that he took in the Catskills, juxtaposing his sketches and paintings with photos of the scene now. Cole’s final product may not compare favorably with, say, The Last Supper; but it would never have occurred to that Italian genius—or, indeed, to any major European painter up to this time—to use hiking as a basis of artistic inspiration. It was a major innovation.

The Thomas Cole National Historic Site includes not only the main house, but several other buildings on the property. There is the visitor center, of course, and also two buildings that Cole designed himself: the Old and the New Studios. The Old Studio—which Cole used for the most productive years of his life—is little more than an adjunct to an old barn, with extra windows for good lighting. The New Studio was wholly designed by Cole, but was demolished in the 70s. It has since been reconstructed according to his design and now serves as an art gallery.

Thomas Cole died young, at the age of 47. But the movement he founded culminated in the work of his star pupil, Frederic Edwin Church (1826 – 1900). As a young artist, Church was a frequent visitor to Cole’s home; and it is easy to picture the young artist admiring the green hillside on the other side of the Hudson. After achieving both fame and wealth far beyond anything Cole could have dreamed of, Church bought himself a huge estate, and erected one of the most startling buildings in the Hudson Valley: Olana.

This property can be spotted from Cedar Grove, as a red dot among the green hills. Indeed, as of 2018, visitors can even walk from Cedar Grove to Olana, thanks to a pedestrian walkway that was affixed to the Rip Van Winkle Bridge. I walked part of the way and recommend the experience, if only for the wonderful views of the river and the Catskills beyond.

(Curious motorists may notice that the road from the bridge curves somewhat awkwardly on the western side. This was precisely to avoid disturbing Thomas Cole’s historic residence.)

Olana presents a startling vision to the new visitor. You see, Church was a remarkably well-traveled man, especially considering that he lived before the age of air-travel. He designed Olana—in collaboration with famed architect, Calvert Vaux—after returning from the Middle East, basing both the design and the name on Persian models. (In this, he resembles an earlier Hudson Valley resident, Washington Irving, who built his Sunnyside after returning from Spain.)

Historically, painting has been a poorly remunerated profession. Van Gogh famously died penniless, but even the great Rembrandt was considered as little more than skilled craftsman. Of course, most aspiring painters still carry the cross of poverty; but in the 20th century it became at least possible for the most successful artists to become independently wealthy.

So how was Church able to afford such an ostentatious house on one of the most attractive bluffs overlooking the Hudson Valley? This was partly the result of an innovative business practice. In addition to having wealthy patrons who supported him and bought his work—the life-blood of artists for centuries—Church hit upon the idea of touring with his paintings. That is, he sold admission to his works, which would be exhibited in well-lit rooms complete with benches, from which the eager audience could view the painting with opera glasses. At the time, it must have been like a trip to the movies.

This idea worked because of how and what Church painted. Like his mentor, Cole, Church was primarily a landscape painter; but he worked on a grander scale—painting enormous canvasses that could occupy the entire wall—and traveled to far more “exotic” landscapes.

His most famous painting, In the Heart of the Andes, is an excellent example. Inspired by the naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, Church traveled to a land where few Westerners had dared to go, and took painstaking care to accurately capture it all on his canvass—from plant species to climate zones. At a time before color photography, when long-distance travel was inaccessible to the vast majority, the painting must have been a startling window into a distant, alien world. It was a David Attenborough documentary for the 19th century. (You can see this enormous canvass in the Met, where it still may steal your breath.)

The house at Olana unites Church’s dominant interests: landscape, art, and travel. The many arched windows open out onto views of the Hudson Valley and the Catskills that are, indeed, worthy of a painting. And in addition to the house’s odd profile—a kind of Victorian imitation of Persian design, altered to suit a cold climate—it is further distinguished by the many stenciled designs that run along the walls, inside and out. Church designed these stencils himself; and along with striped awnings and colorful roof tiles, they serve to give the house a visual flair quite foreign to most American mansions.

The furnishing of the house reflects Church’s wide travels, as various knicknacks from Mexico and the Middle East are scattered among the elegant furniture. But the main thing the visitor sees are paintings. There are dozens of them—not only by Church, but also Cole and other artist acquaintances. The vast majority of these are landscapes, which again demonstrate both his immaculate technique and his wide travels. Compared to Cole’s more staid style, Church is a cinematic painter, whose landscapes transport you into another world. I would certainly have paid admission to see one.

In addition to Church’s home, the visitor can enjoy his estate, which must be one of the most attractive pieces of property in the entire Hudson Valley. But as it happened, we had to go west on the day we visited; so instead of strolling on the carriage roads, we got in the car and headed to a site on the Hudson River Art Trail: Kaaterskill Falls.

The name of this waterfall—like the name of the Catskills themselves—comes from “cat” (as in bobcat, which presumably were more common in earlier times) and “kill,” an old Dutch term for a stream. Indeed, throughout New York, the curious visitor will find many streams bearing ominous names, like the Sing Sing Kill or Beaverkill.

The falls are magnificent. A stream of water plunges down over 200 feet from a sheer cliff, making them taller than Niagara Falls, if orders of magnitude less powerful. It was largely thanks to Thomas Cole that the falls became a popular tourist attraction in the early United States, who was the first of many to popularize the cascade in paintings. On the day we visited, there were people swimming in the murky pool below, while dozens looked on, awestruck. It is easy to see how Cole was inspired to start a new artistic movement by this landscape.

5 thoughts on “Historic Hudson Homes: Cedar Grove & Olana”