The Canary Islands are one of the treasures of Spain. Culturally Spanish, they are geographically and climatically quite unlike Europe or even the relatively closer African coast. They are, rather, a world unto themselves, each one quite distinct from the other—products of wind, waves, and volcanism.

Gran Canaria, despite its name, is neither physically the largest island (that is Tenerife) nor the most populated (Tenerife again), but it is home to the largest city in the archipelago: Las Palmas. (Confusingly, there is another island named La Palma; and the capital city of yet another Spanish island, Mallorca, is named Palma.) Home to nearly 400,000 people, it is a proper metropolis, with its suburbs stretching for miles all around.

As our Airbnb was in the outskirts of this mighty municipality, we decided that we ought to make Las Palmas our first stop of the trip. We headed first to the city’s cathedral. It fronts an attractive plaza lined with (what else?) palm trees and buildings sporting the colorful façades typical of the city. The cathedral looms overhead without being particularly grand or beautiful from the outside. It is more charming in the nave, where the stone columns imitate palm trees in their leafy spread. But I had to say I did not enjoy the view from the towers, which was of rather ugly urban sprawl.

That being said, although I am sure many parts of the city are, like any city, rather bland and devoid of character, the historic center of La Palma is indeed quite lovely. We strolled around, peaking into a few shops, taking note of restaurants, until we arrived at our next destination: the Pérez Galdós House Museum.

Though comparatively obscure outside of Spain, Benito Pérez Galdós is one of the most iconic writers within the country. For reference, if Cervantes is the Spanish Shakespeare, then Galdós is the Spanish Dickens. He was, in other words, an extraordinarily prolific novelist who stood at the height of the Spanish literary world during his lifetime—both praised by critics and adored by the public. And although many of his most notable stories are set in Madrid—a Madrid as carefully delineated as Dickens’s London—it was from this tropical island that the great writer hailed.

Despite his fame and the strong sale of his books, Galdós never owned a house in the capital city. Instead, he stayed with his nephew as a kind of long-term guest. A lifelong bachelor (though with many lovers), this arrangement seemed to suit his habits just fine. In his later years, Galdós did eventually buy a house, but in Santander (on the northern coast) rather than in Madrid. (Like many madrileños, Galdós escaped the suffocating heat of summer by fleeing north.) And yet it is not that house, but his childhood home in Gran Canaria, which eventually became his museum.

You can only visit the house via a guided tour, but our tour was excellent. The house is of fairly modest dimensions—two floors, with a sizable patio in the middle. No attempt has been made to furnish it as it might have been while Galdós was a boy. Instead, his furniture and decorations were brought here from his home in Santander. This may sound like an odd decision, as it achieves neither an authentic reconstruction of his childhood or adulthood. But it was done so intelligently and tastefully that, somehow, I felt I was getting to know Galdós on an intimate level.

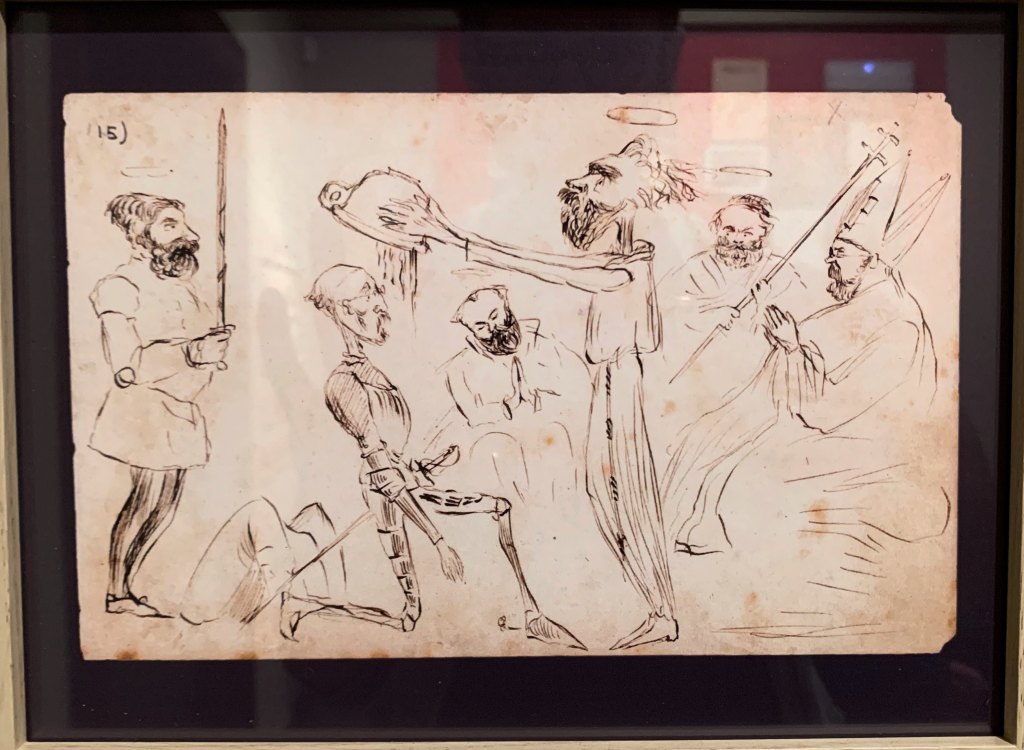

He was a man of many surprising talents. Aside from his obvious literary ability, Galdós was, for example, a skilled pianist. Indeed, he was quite the music enthusiast, and even devoted much of his time to writing criticism of performances. Galdós was also a decent draftsman. In the exhibition room near the entrance to the museum, you can see many examples of his sketches, some of which are of the characters from his books. Most surprising to me, however, was his ability as a woodworker. Much of the furniture in the museum was made with his own hands, and it is very fine work indeed. Surrounded by all of this, you get the impression of a man bursting at the seams with brilliance.

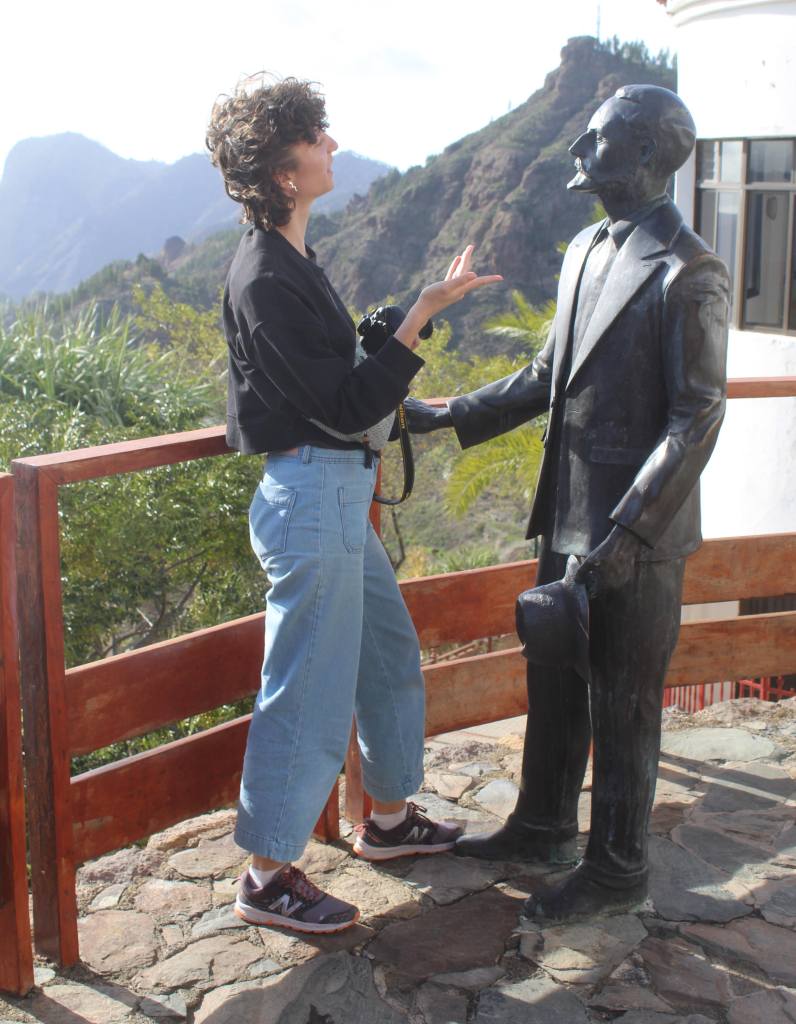

The tour ends with the rough version of the official Galdós monument—the real version of which stands in Retiro Park, in Madrid. (Next to it, there’s a little public library shelf where I donate my books.) I emerged from the museum feeling quite inspired. While he may not be my favorite author, Galdós lived his life fully devoted to art in a way few of us mere mortals can imitate. He is a true literary hero.

After this, we ate a delicious lunch at the Moroccan restaurant across the street to recover our strength. Then, we headed to another excellent museum: El Museo Canario.

Though you may think from its name that this museum would be devoted to all things Canary, its collection is exclusively devoted to exploring the islands’ original inhabitants: the Guanches. (Properly speaking, the “Guanches” was but one group of the islands’ inhabitants, but the name is commonly used to refer to all of the indigenous people collectively.)

The Canary Islands have been inhabited for thousands of years, starting perhaps as far back as the sixth millennium BCE. There is evidence of trade between the islands and several ancient civilizations, including the Phoenicians and the Romans. However, at some point contact with the mainland was lost. What resulted—as seems to be the general rule in isolated peoples—was a kind of technological reversion. By the time the Spanish made contact with the Guanches, they had lost the ability to navigate the open ocean. Indeed, they were literally a stone-age people, making tools out of wood, bone, and rock, and painting caves.

Contact with the Spanish proved disastrous. Much of the original population was wiped out. Not that they didn’t fight back. At the First Battle of Acentejo, for example, the Guanches killed nine out of every ten Spaniards. Yet, in the long run, they had neither the numbers nor the technology to resist European colonization. Those who escaped slaughter gradually integrated into Spanish society, losing their culture. And because none of the colonizers saw fit to write down more than a few sentences in the native language, it has mostly been lost, too. What remains of their language and their bones reveals, as expected, a link with North Africa. But it is tragic to consider how we must now make guesses about a culture which existed until the 1500s, as if they were an ancient people.

The Museo Canario began in the late 1800s as a kind of private project among a group of intellectuals, under the mistaken belief that the archaeological remains were related with the European paleolithic. Indeed, the museum’s collection is housed in the former home of the leader of this group, Gregorio Chil y Naranjo (who must have been quite a wealthy man). By any standard, the museum’s collection is excellent—with stone tools, ceramics, and even a reproduction of the cave paintings in Galdar (though I wish we had gone to see the originals). Best of all—and strangest—is the so-called “Idol of Tara,” which is a ceramic cult statue depicting a seated woman. Her proportions are, however, rather strange—with enormous thighs and shoulders, but an exceedingly tiny head. Rebe thought it was very funny.

Yet the most memorable part of the visit were the bones. In one room, assembled like a cabinet of curiosities, are the bones of dozens of Guanches on display in glass cupboards. There are even a few mummified bodies. It is quite an impressive sight, I admit, though it did give me some misgivings. I doubt, for example, that we would condone digging up and displaying bones from the European Middle Ages in the same way. Indeed, as it was the Spanish who were responsible for the extinction of their culture, it does strike me as adding insult to injury to treat these erstwhile human beings as decoration. But perhaps I am being overly scrupulous.

This did it for our sightseeing in the capital. After this, we made a quick stop in the nearby town of Arucas. On the way, we got a taste of capricious Canary weather. In mere minutes, it went from sunny to pouring rain, and the car briefly hydroplaned a couple times as I drove through flooded roads. By the time we arrived, however, the skies had largely cleared, and we were able to walk around without umbrellas. Arucas is famous for two landmarks. First there is the massive neogothic church of San Juan Bautista, which seems out of all proportion to the modest town surrounding it. The other is the famous Arehucas rum plant. Unluckily, it had closed just before we arrived, so we couldn’t take a tour. But I must admit that, when I bought a little bottle to try for myself, I wasn’t especially fond of the liquor. I prefer brandy or whisky.

Next we stopped in the nearby town of Firgas. This attractive village is primarily famous for the Paseo de Canarias, which is a long fountain running alongside a walkway. The fountain is decorated with three-dimensional maps of the Canary Islands, along with their flags and coats of arms. Aside from this touristy eye-candy, however, Firgas is just a nice place to stop and have a coffee or a bite to eat.

On our next day in Gran Canaria, we headed south. Our first stop was the Maspalomas. We parked the car in a kind of suburban beach community, near an oddly gaudy building that I took for a kind of amusement park (but was actually a shopping center), and started walking towards the ocean. We were there to see the dunes. When they came into view, I was stunned. It is the sort of thing that you expect only to exist in film studios—mountains of sand, rolling into the distance, surrounded by the crystalline blue sea. Apparently, during the last age, when the ocean was considerably lower, sand from the erstwhile ocean floor was washed up. This result of this long geographical process is perfect for Instagram.

We left the wooden walkway to stumble around the dunes. Though it was December, the sun was blindingly intense on the sand. Just moving around on the dunes was strangely exhilarating—either waddling up the steep hills and causing a miniature rockslide in the process, or nearly falling as the sand gave way beneath you on your trip back down. But after about half an hour of that, I’d had my fill of sand and yearned for solid ground.

After this, we suffered a bit of confusion. Rebe had read that Mogán was one of the most beautiful beach towns on the island, and so we set our GPS to that location. But when we turned away from the ocean and into the rugged, dry interior, I began to feel that something was off. The drive was interesting—winding through a valley, passing town after town, many of them charming—but the beach did not seem to be forthcoming. Finally, we arrived at Mogán, and parked near a basketball court. The town had a kind of shabby, neglected appearance (no offense) that did not seem to mark it out as a tourist hotspot.

Soon, our error was revealed: the famous town was Puerto de Mogán, not Mogán itself. In fact, we had basically driven right past it before we turned inland. Thus, we got into the car and headed back toward the coast.

Puerto de Mogán is, indeed, a beautiful beach town in a lovely natural setting. The low, white buildings cluster around the bay, while volcanic hills jut up to the left and right. It is also, however, a good example of how tourism can ruin a place. The seaside was full of oversized, overpriced, and badly-reviewed restaurants, while the streets had little more to offer than tourist knicknacks. There was not even an inviting place to have a coffee. Still, the place itself is undeniably attractive, as we found while observing the bright orange grabs darting among the jagged rocks, swept about by the waves.

But we were hungry, and—as mentioned—the town was bereft of decent restaurants. Rebe got on her phone and discovered that there was a promising restaurant in, of all places, Mogán—the town we had just visited. So we got in the car and drove back up the valley to the town, parking in the same parking space, in order to eat in the Restaurante Canario de Oro. There, the owner recommended several local dishes to us which we duly ordered and shared. It was quality local food.

This did it for our time on the south coast. To return to the north, we decided to drive through the center of the island. The road took us high up into the mountains in the interior, until we approached the highest peak, the Pico de las Nieves. Unfortunately for us, during the drive the weather turned from pristine blue skies to downcast to downpour. By the time we got to the mountaintop, ice-cold rain was lashing down, and we decided not to get out of the car. There wouldn’t have been much of a view, anyway.

On the way down the other side of the mountain, we stopped in a village called Tejeda. Under normal circumstances, I am sure it is a beautiful little town. But with the wind and biting rain, we could only think of getting inside somewhere. We ended up in a bakery, where we had a few of the local pastries to recover our strength. But I’m afraid I saw very little of Tejeda.

By the time we reached our next stop, Teror, the weather was clearing up a little. Its name notwithstanding—which goes back to the Guanches—there is nothing terrible about Teror (except for finding a parking spot, perhaps, as that was a little stressful). The town center is well-preserved and extremely charming, indeed probably the loveliest we saw during the trip. True, there isn’t very much to do, but just strolling through and peaking into buildings here and there was quite enough. Though I would hesitate to put the difference into words, Canarian towns in general have a distinct style of architecture and layout that makes them unlike their counterparts on the Spanish mainland. And Teror is an excellent example of this.

By the time we finished our stroll and found the car, the sun was setting. We still had one more full day in Gran Canaria to go.

Our first stop the next day was Los Tilos de Moya, one of the great natural parks on the island. Despite its being relatively well-known, I was surprised not to find any kind of official parking lot—or, indeed, any other visitors at all. We left our rental car next to an out-of-business restaurant and embarked on the 2km circular hike, with no other humans in sight.

“Tilo” translates as laurel to English, and this reserve is regarded as a representative of the large laurel forests that once covered the island. The hike was very pleasant—easy and short, while giving us a taste of the lush greenery of the tropical island. But I must admit that I apparently have no idea what a laurel tree looks like, as I could not identify a single tree as belonging to that species. As I discover from a google search, the sort of laurel that grows in the Canaries is not the same species as the one we use to season our food. In any case, it sure does make an attractive forest.

After our little hike, we drove to the northwestern coast, to the town of Agaete. This town was previously famous for being the best place to catch a glimpse of El Dedo de Dios, a precarious rock formation that looked like God’s finger pointing upwards. Unfortunately, however, a storm broke off the index finger in 2005, and God has been making a fist ever since. Nevertheless, Agaete is well worth visiting for the attractive maritime promenade and the natural pools that have formed in the volcanic rock next to the ocean.

Though it was December, there were quite a few people in the water. Rebe and I were not quite so brave. Instead, we walked along the shore taking photos. On the way into town, we passed the Monument to the Poets—a statue commemorating three modernist Canarian poets of the early 20th century. Once we got to the bay, we caught a glimpse of the departing Fred Olsen, a ferry that runs between Gran Canaria and Tenerife—a trip of about an hour and a half. This part of town was full of restaurants, some of which seemed like tourist traps, but several of which looked actually quite nice. We chose one with a view of the beach and had an absolutely terrific lunch. It was Spanish food at its best: cheap, healthy, and dripping with olive oil and garlic.

After this, we headed back into the interior of the island, to Artenara. This town is located far up in the mountains, 1200 meters (or 4000 feet) above sea level. Getting there took some time, as I kept distrusting my GPS. Several times, I was instructed to turn onto something that did not appear to be a real road, and so I disobeyed. Then I was rerouted to yet another unpromising little path. Finally, I decided I had to accept my fate, and I turned into a narrow dirt road.

No sooner had I done so but another car came the other way. The path was too narrow for two cars and had no shoulder, so I was forced to awkwardly back out back onto the road to let the other driver pass. For the rest of my time driving on the road, I was in a panic lest anyone else come the other way, as there was absolutely no space I could squeeze into to let anyone pass. One side of the road was a rock wall, and the other side a steep dropoff. Thankfully, nobody did come, and we made our way to Artenara.

The view alone would have been worth the stress. But Artnenara is also home to a unique museum. After the destruction of the native Guanche population, the incoming Spanish sometimes took over the vacated cave dwellings and turned them into their own habitations. This museum is a kind of recreation of what one of these cave houses might have been like. It was rather bizarre—European sensibilities squeezed into a subterranean context—but oddly fascinating.

This did it for our trip. After Artenara, we went back to the Airbnb, and flew back to Madrid early the next day. Once again, the Canary Islands had surprised us with their richness, variability, and beauty.